Child health care researchers and practitioners have a responsibility to ensure the health of the pediatric population. An important new question is whether recent changes in the burden of childhood disease and disability are reflected in the National Institute of Health (NIH) allocation process. Existing and new childhood adversities pose deleterious consequences on health and well-being. Take the leading cause of death among children. In 2020, firearm injuries became the leading cause of death among children and adolescents, exceeding those caused by motor vehicle crashes. From 2019 to 2020, the relative increase in the rate of firearm deaths of all types (suicide, homicide, unintentional, and undetermined) among children and adolescents was 29.5% – more than twice as high as the relative increase in the general population (Goldstick, Cunningham, & Carter, Citation2022). Understanding emerging child health challenges which pose the greatest threat to health and wellbeing can help NIH leaders decide how to use limited resources for maximum benefit. We offer an update on the NIH child health research portfolio and conclude that we might realign priorities to address new forms of childhood adversity.

Despite an overall increase in NIH child research funding, scholars have noted that funding across diseases and conditions is uneven and insufficiently responsive to the changing burden of disease (Rees, Monuteaux, Herdell, Fleegler, & Bourgeois, Citation2021; Gordon & Corwin, Citation2022; Goldstick et al., Citation2022; Grummitt et al., Citation2021; Rockey & Wolinetz, Citation2015). The NIH reports that it recognizes the importance of the responsiveness of funding to the burden of disease as one of many considerations for setting research funding priorities.Footnote1 The NIH does not attempt to apply a one-size-fits-all approach to the burden of disease in funding decisions. It considers multiple data sources and examines each disease category on a case-by-case basis when determining the best strategy for the allocation of funds. However, research funding for existing and new child health challenges has been variable and insufficient. As a result, the NIH child health research priorities should be evaluated at regular intervals to meet changing individual and population health challenges.

The NIH child health research portfolio is defined as the total funds obligated to conduct or support pediatric research.Footnote2 To improve consistency in reporting, the NIH implemented a process through the Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system in 2008.Footnote3 The NIH does not expressly budget by category. Funding is tracked for specific diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease or breast cancer), for various conditions (e.g., infertility or obesity), and for specific areas of research (e.g., genetics or substance abuse). Pediatrics is reported as a specific category in the RCDC and defined as “humans aged 0–21 including embryo/fetus” (Gitterman, Hay, & Langford, Citation2022). Currently, five institutes – NICHD (16.7%), NCI (10.9%), NIAID (10.6%), NHLBI (8.95%), NIMH (8.75%) – account for most of the child health research funding.

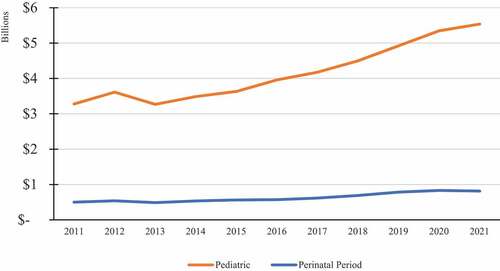

There is promising and challenging news to report in 2022. The child health research portfolio has increased from $3.3 to $5.5 billion during the last decade – a 67% increase (Gitterman et al., Citation2022). The perinatal (i.e., conditions originating in perinatal period) portfolio has increased from $498 to $814 million – a 63% increase (National Institutes of Health, Citation2021; ).7 In addition, research spending on “preterm, low birth weight, and health of the newborn” increased by 113%; and “conditions affecting the embryonic and fetal periods” increased by 89%. Within the last half decade, the NIH has reported new data on annual funding for pregnancy ($500 million), infant mortality ($130 million), and maternal health and maternal morbidity and mortality ($400 and $240 million). These funding increases are very promising maternal and child health developments, for many adult health risks (e.g., obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and immune diseases) are influenced by life events before and throughout pregnancy, and during early childhood. Prevention in the pediatric age group of adult-onset disorders can reduce health care costs that otherwise would increase exponentially over the lifespan much more than trying to treat them after they appear clinically in adults.

Figure 1. NIH Child and Perinatal Portfolio, 2011–21 (nominal dollars) Note. All of the projects in the following publicly reported subcategories are reported in the pediatric (child and adolescent) category because of reporting rules: adolescent sexual activity; cerebral palsy; child abuse and neglect research; childhood injury; childhood leukemia; childhood obesity; conditions affecting the embryonic and fetal periods; congenital heart disease; congenital muscular dystrophy; congenital structural anomalies; Cuchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy; fetal alcohol spectrum disorders; infant mortality; neonatal respiratory distress; osteogenesis imperfecta; pediatric AIDS; pediatric cancer; pediatric cardiomyopathy; perinatal period – conditions originating in perinatal period; polycystic kidney disease; preterm, low birth weight and health of the newborn; Rett Syndrome; spina bifida; spinal muscular atrophy; sudden infant death syndrome; teenage pregnancy; underage drinking; unintentional childhood injury; youth violence; youth violence prevention. (RCDC Team, 2022).

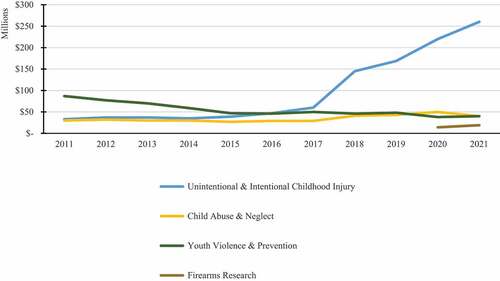

While pediatrics is reported as a broad category in the RCDC, childhood injury and unintentional childhood injury are reported as distinct categories as well. Childhood injury has benefited major funding increases of 688% (accidental) and 325% (intentional).Footnote4 However, research on youth violence and youth violence protection has seen significant decreases from $87 to $40 million (−54%) and $26 to $22 million (−18%). In addition, research funding for child abuse and neglect has been almost stagnant, decreasing from $50 to $40 million in the last 2 years ().

Figure 2. Child health Portfolio and Categories of Childhood Adversity, Fiscal Year, 2011–21 (nominal dollars) Note. The childhood injury category includes research on injuries suffered from the fetal period to age 21, including physical child abuse and youth violence. The unintentional childhood injury category includes research on unintentional injuries suffered from the fetal period to age 21, including accidents. All the projects in the unintentional childhood injury category are reported in the childhood injury category (RCDC Team, 2022).

There is also limited publicly-accessible pediatric data on other leading causes of death. For example, suicide is a leading cause of death among adolescents aged 15–19 years. Although (entire population) suicide and suicide prevention have seen major increases, 186% and 220% over the last decade respectively, there is no pediatric-specific funding data reported on mental health, suicide, and suicide prevention research. Moreover, drug overdose and poisoning increased by 83.6% from 2019 to 2020 among children and adolescents, becoming the third leading cause of death in that age group. However, no pediatric-specific funding data is reported beyond the drug abuse research category. In addition, childhood obesity funding, a major health crisis starting in the perinatal period, infancy, and childhood, decreased by $15 million in the last year and remains a small percentage of overall research spending on obesity (for the entire population).

Let us turn to the leading cause of death among children and adolescents. The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 45,222 firearm deaths in 2020 – a new peak. It is remarkable that firearm injuries have become the leading cause of death among children and adolescents, exceeding those caused by motor vehicle accidents Goldstick et al., Citation2022). Firearm homicides disproportionately affect younger people in the United States, and we are alone among peer nations in the number of child firearm deaths. In no other similarly large or wealthy country are firearm deaths in the top four causes of mortality, let alone the Number 1 cause of death among children. However, for more than two decades, no dedicated federal research funding existed for gun violence and injury prevention until in 2020 when the U.S. House of Representatives included $25 million for gun violence research, split evenly between the CDC and NIH. The NIH has funded and reported firearms research for only the past 2 years, investing a modest $14 and $19 million in funds in 2020 and 2021 (National Institutes of Health, Citation2021).

Child health researchers and clinicians can be on the front lines of documenting forms of childhood adversity and help build solid evidential foundation to understand causes and to develop and administer treatments and preventions. The NIH can support research to identify and evaluate evidence-based methods to reduce firearm injuries and trauma and reverse the increase in childhood deaths due to gun violence. With allocation of resources to align with need, researchers can identify the behaviors and environments most likely to contribute to severe, devastating, or fatal injuries and educate children, adolescents, and parents how to avoid them. The more traumatic or adverse the events that children have, the higher the risk for negative health effects that can continue into adulthood.

However, we reject pitting research funding for any one child health challenge or condition against another, which we would consider a defeatist approach to promoting increases in overall child research funding. To improve the health of children and future adults, it is imperative that the U.S. prioritize investments in all types of basic, clinical, and child health research that is focused on new (and existing) challenges that adversely affect children and create an unacceptable burden that lasts a lifetime.

Abbreviations

NIH – National Institutes of Health, NICHD – National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NCI – National Cancer Institute, NIAID – National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NHLBI – National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIMH – National Institute of Mental Health, U.S. – United States of America

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in the editorial are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of the editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The burden of disease is the impact of a health problem on physical, mental, and social development, not only on the affected individual, but also on society. Many indicators exist for the burden of disease, including prevalence, incidence, mortality, morbidity, extent of disability, and financial cost.

2 Pediatric is defined as “humans aged 0–21 including embryo/fetus” (RePORT Support Team 2022).

3 The research category levels represent the NIH’s best estimates using the category definitions. These definitions include all aspects of the topic (e.g., basic, pre-clinical, clinical, biomedical, health services, behavioral, and social research).

4 Injuries are commonly categorized by mechanism (i.e., suffocation, drowning, falls, fires and burns, poisoning, transport) and intent (i.e., unintentional, suicide, and homicide).

References

- Gitterman, D. P., Hay, W. W., & Langford, W. S. (2022, July 7). Making the case for pediatric research: A life-cycle approach and the return on investment. Pediatric Research. Special article. doi:10.1038/s41390-022-02141-5

- Goldstick, J. E., Cunningham, R. M., & Carter, P. M. (2022). Current causes of death children and adolescents in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 386, 1955–1956. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2201761

- Gordon, J. B., & Corwin, D. L. (2022). National Institutes of Health funding priorities. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(3), 323–324. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5371

- Grummitt, L. R., Kreski, N. T., Kim, S. G., Platt, J., Keyes, K. M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2021). Association of childhood adversity with morbidity and mortality in US adults: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(12), 1269–1278. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2320

- National Institutes of Health. (2021, May 16). Estimates of funding for various research, condition, and disease categories. NIH RePORT. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://report.nih.gov/funding/categorical-spending#/

- Rees, C. A., Monuteaux, M. D., Herdell, V., Fleegler, E. W., & Bourgeois, F. T. (2021). Correlation between National Institutes of Health funding for pediatric research and pediatric disease burden in the US. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(12), 1236–1243. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3360

- Rockey, S., & Wolinetz, C. (2015). Burden of disease and NIH funding priorities. NIH Office of Extramural Research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34605870/