ABSTRACT

The present contribution starts from the debate about kinship as a social institution in medieval Europe initiated by Jack Goody's pioneering anthropological work in the 1980s and drawn upon by historians and anthropologists alike. We focus on the aspect of the allegedly systematic separation of kinship from the organization of memory of the dead brought about by the establishment of Christianity. However, throughout the European Middle Ages families did not completely cede memorial tasks to religious institutions. Rather, they re-affirmed memorial bonds to religious institutions by legal arrangements and through family members within these communities, just as kinship continued to play a key role in medieval political organization. Given their social heterogeneity medieval cities provide a rich documentation of networks across ties of family, kinship, friends, and clients that intersected with more institutionalized communities (parish churches, monasteries, hospitals). People bestowed economic benefits on these communities in return for their members' “eternal” prayer for the donators' souls. This created mutual bonds both between kin and religious communities. The ensuing forms of belonging were part of a more complex frame of social exchange, as families used the same institutions as “hubs” to corroborate social and political relations to their peers. These bonds would intersect with ties between representatives of kin groups with positions in key political organizations such as city councils. A further clue to understanding these relations is gender. Economic transactions and related memorial practices feature a considerable number of female actors underlining the salience of bilateral kin relations and practices of property devolution.

Introduction

Inspired by post-structuralist social anthropology (Parkin and Stone Citation2004) and by new critical reflections on the mechanisms of historical change, kinship during recent decades has regained salience as an explanatory concept for historical research (Sabean and Teuscher Citation2007; Algazi Citation2010; Duindam Citation2021). Drawing on the classic work by social anthropologist Jack Goody (Citation[1983] 2012), the medieval historian Bernhard Jussen (Citation2013) has argued that, in a global perspective, kinship as a social institution was structurally ‘weaker’ in medieval Europe than in other parts of the world and in Roman antiquity, when it played a key role in the maintenance of family memory.Footnote1 Goody had argued that this fundamental change was brought about by two factors related to Christianity: first, the religiously fostered career of the monogamous and indissoluble marriage resulted in predominantly bilateral kinship structures; second, this process was tied to economic strategies of the Christian Church that developed an interest in material wealth, which in turn made it necessary to adjust secular and ecclesiastical law due to its consolidation as a property-holding corporation (Goody Citation[1983] 2012). Building on this set of arguments, Jussen (Citation2013) maintained that the new post-Roman kinship structures no longer covered the organization of memory for the dead. Since Carolingian times at the latest, care for the dead had become a task of religious institutions, above all monasteries and parish churches that received large amounts of property and other material benefits in return for their memorial services.

In this contribution we suggest that bilateral kin groups’ memorial practices were in fact deeply interwoven with these new institutions of care for the dead and intricately entangled with the same groups’ practices of property management. Although perhaps not as structurally ‘strong’ as in Roman antiquity, kinship in medieval Europe obviously ‘mattered’, yet in a very different manner than before, as David W. Sabean, Simon Teuscher and many others have aptly shown (Sabean and Teuscher Citation2007; Ubl Citation2008; Spieß Citation2009; Sabean and Teuscher et al. Citation2011; Morsel Citation2014). But how exactly did it ‘matter’ structurally? First, only from the 15th century were kin groups more systematically forged into the logic of genealogy. Likewise, far into the early modern period, with its overall increase in institutional forms of government, kinship played a key role as a structuring principle in many forms of social and political organization. These included princely courts, urban councils, religious orders and confraternities, as well as corporate occupational groups and rural communities (Sabean and Teuscher Citation2007; Duindam Citation2021). Second, recent research has also shown that throughout the European Middle Ages kinship did not completely cede its function to religious institutions as the site of family memory. Rather, families re-affirmed memorial bonds to religious houses not just by legal arrangements, but also by means of strengthening their ties to them through family members who were simultaneously members of these communities (Geuenich and Oexle Citation1994; Borgolte et al. Citation2014–2017; Signori Citation2021).

Against such a research background of novel dynamics in evaluating kinship in medieval Europe as one of many parts of a global world, the present contribution sets out to rethink the role of family and kin in their relations to other social and, above all, religious institutions. It starts from the close linkage between social and religious motivations observable in many forms of pre-modern European social organization. Socially heterogeneous urban spaces are exemplary in their overlaps between ‘secular’ and ‘ecclesiastical’ cultures. Interactions within networks across family, kinship, friends and clients often intersected in more institutionalized communities such as parishes, monasteries, confraternities or charitable institutions (cf. Terpstra Citation2000, Citation2013; Lynch Citation2003; Korpiola and Lahtinen Citation2018). People bestowed benefits on these institutions in return for their members’ provision for welfare and prayer for the donators’ souls. Hence, donations and other legal interactions with religious and charitable communities created mutual bonds between urban elites both with these communities and among one another.

How then can we assess the role of kinship in urban environments? How did it concretely work as a social mechanism? Central European towns like Bern, Basel, or Konstanz (Constance) to the west, Vienna, Budapest (Buda), or Bratislava (Pressburg) more to the east are cases in point, although less widely known than the prominent towns and cities that constituted Mediterranean or north-western European urban landscapes.Footnote2 In what follows, we will address the multidimensional modes of social and spiritual exchange that we refer to as ‘spiritual economy’ by focusing on communities of kin and religious communities in Central European towns.Footnote3 Our case studies on Vienna and Pressburg will focus on urban actors and their local, regional and trans-regional networks. We will, first, argue that kin communities and religious communities were two key social institutions at the centre of a complex web of social exchange: kin groups used religious institutions of all kinds – parish churches and chapels, monasteries, hospitals and confraternities – as integrative ‘hubs’ to corroborate or activate social and political relations to their peers. Agency and alliance will thus be integrated into the focus of this analysis, in addition to matters of inheritance and descent (for a broad overview on these relations in historical rural Europe see Segalen Citation2021).

Second, in order to better understand the binding character of these ties, we will focus on gender as a further key dimension in this framework. Women are represented in considerable numbers in the documentation of memorial practices and economic transactions involving religious institutions. Their prominent role in these legal acts underpins the salience of bilateral kin relations that both regional inheritance laws and practices of property arrangements amply show (Lentze Citation1952/53; Demelius Citation1970; Bonfield Citation1991; Martin Citation1993). By contrast, sustainable ties between kinship networks that are centred on lineages and political institutions can rarely be traced beyond two or three generations before the 15th century (Spieß Citation1993). This seems to correspond to local and regional mechanisms of social mobility, for instance changes within and re-grouping of urban elite groups in town councils over the same period of time (Gruber Citation2013; Majorossy Citation2021).

These observations fit in with an important suggestion made by Sabean and Teuscher (Citation2007). According to them, kinship relations in medieval Europe balanced patrilineal and bilateral principles far into the early modern period. Modern state building and the emergence of stable genealogies were twin phenomena: on the one hand, from the 15th century onwards an overall trend towards stronger patrilineal patterns is obvious. Families started to regulate the succession to titles and offices in an increasingly severe manner, thus maintaining patrimony and social status and institutionalizing their political power within the lineage. On the other hand, kinship remained ‘fundamentally bilateral’ as an organizing principle of key aspects of social life, such as providing for the next generation by means of shared property management, sustainable support and political networking.

An Example: the Poll family in Vienna

In the 13th century, the Poll family settled in and around Vienna, having moved there from neighbouring Bavaria, probably from Regensburg. Members of this multi-branched family were soon mentioned among the local elites. One or two generations after their arrival, Konrad Poll was the first mayor of the city under Habsburg rule (1282). He married a daughter of a Cologne merchant and inherited a town house that incorporated a private chapel dedicated to the saints Philip and James and was centrally located on Vienna’s meat market (Fleischmarkt). The family’s wealth was based on mid-range inter-regional textile trade and likewise on large-scale management of landed property and feudal rights that its members gradually accumulated over major parts of the Duchy of Austria, which at the time embraced today’s territories of Lower Austria and Styria (Perger Citation1967/1969, 82–86).

The Poll family was typical of a generation of urban elite members that is increasingly well documented from around 1300 onwards, when the Habsburg dynasty took over the rule of the Austrian duchy from King Ottokar II of Bohemia, who had followed the first ruling dynasty of the Babenbergs (Csendes and Opll Citation2001). When the Babenbergs established their power in Austria in the 12th century, one of their most effective strategies was the foundation of religious houses as their political partners: first in their core regions, then parallel to the spread of new settlements eastward along the Danube, which resulted in a rich monastic and urban landscape. As in many Central European regions, towns and cities were strongly influenced by the territorial lords, who mostly also acted as town lords. Hence they provided towns and monasteries with a variety of privileges and, in turn, profited from urban and monastic prosperity. This interdependency extended to Babenberg dynastic followers and likewise to other noble families with landed property both in Vienna and in the wider region. Strong bonds and structural similarities between urban elites and rural nobility are characteristic features of the region (Gruber et al. Citation2013; Clark and Simms Citation2015; Lutter Citation2017) ().

Marital strategies

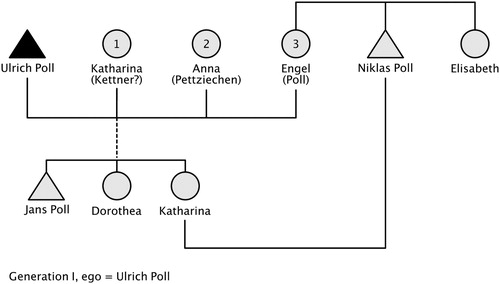

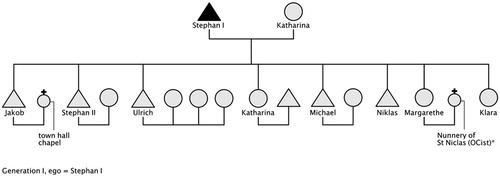

In the first half of the 14th century Konrad Poll’s family network increasingly widened, especially through the progeny of his sons Stephan and Niklas: Stephan had at least eight children and Niklas had seven, who all reached adulthood and old age. Traces of some other family members disappear after 1349/50 on account of the Black Death (bubonic plague) (Perger Citation1967/1969, 82–86). All known members of this generation, however, married well. They adopted a marriage pattern of clear regional isogamy in a loose sense of the term corroborating or extending existing ties with Viennese families of merchants and office holders, above all town council members (for European dynastic kin networks cf. Duindam Citation2021) ().

Figure 2. Stephan’s and Katharina’s children incl. in-laws (right). * Entries into monasteries are displayed as marital links in the contemporary sense of a ‘marriage to Christ’.

For instance, Niklas’ daughter Margarethe married a member of the Smausser merchant family who was active in Venetian trade. She also arranged marriages for several of her own children into some of the city’s then most prominent families, e.g. the Holzkäufel, Kettner, Schemnitzer, Würffel and Zink. All of these were represented on the town council between 1370 and 1400 (Simonsfeld Citation[1887] 1968, 76; Perger Citation1980, 102–104). Likewise, throughout the 14th century male members of the Poll family succeeded in occupying several prestigious positions. For instance, in the 1320s and 1330s Niklas Poll was Vienna’s acting mayor over several periods of office, while one of his nephews, Ulrich, was town treasurer, and another, Stephan, held the position of a ducal mint master. Almost every year between 1359 and 1389 either of them sat on the town council (Sailer Citation1931, 8–30).

Marital relations corresponded with political alliances and formal friendships with council members, so-called Ratsfreundschaften, and accordingly worked by way of reciprocity: solidarity through office corroborated relationships through marriage and vice versa (cf. Seidel Citation2009). These intermarriages within the urban elites of Vienna can be seen as an indicator for their active strategies to strengthen existing peer relations and thereby establish a robust power base. Consequently, to counter these efforts and in accordance with contemporary ecclesiastical law, the Habsburg duke Rudolf IV in his function as town lord in 1364 issued a decree that forbade marriages of either boys or girls against their will (Csendes Citation1986, 140).

Another effective means of strengthening ties between two more distant family branches were marriages between in-law family members. Stephan Poll’s son Ulrich provides a good example for this strategy: he married twice into peer families and outlived both wives. His third wife came from a different branch of the Poll family: Ulrich married Engel, a daughter of Jakob Poll. Engel’s brother Niklas, in turn, married Ulrich’s daughter from his first marriage, Katharina, who was by then widowed herself. Thus Ulrich was Niklas’ brother-in-law and father-in-law at the same time. As a consequence, the resulting provisions for inheritance, i.e. divisions of property between Niklas and his sisters on the one hand, and Niklas’ stepchildren on the other, were laborious and very detailed ().Footnote4

Moreover, the Poll family established hypogamous marital connections with members of the ducal court. Niklas’ son Berthold was married to Katharina, a daughter of Duke Albrecht’s II gatekeeper, then an important ducal office (QGStW II/1, n. 449). Bonds with noble groups residing in the vicinity of Vienna, and likewise with groups of burghers in nearby smaller towns, diversified the profile of the Polls’ network. They testify to permeable boundaries between urban elites and town-based nobility. Conversely, burghers acquired landed property as well as feudal rights in the surroundings of Vienna. They corroborated or promoted their kin-based ties by means of wide-reaching arrangements of selling, subletting, and exchanging property, which included mutual loan and credit transactions (Frey and Krammer Citation2019; Lutter Citation2021).

These widespread practices were at least to some extent at odds with legal norms concerning inheritance. Like in other Central European regions, Vienna’s inheritance law clearly privileged all direct male and female descendants, which means that they basically had a right to an equal share of their parents’ property (on partible/impartible and thus egalitarian/inegalitarian patterns see Segalen Citation2021).Footnote5 However, as we have seen, both consecutive marriages and the social and political weight of bilateral kin relations complicated the picture. They led to conflicts both among in-laws and between generations and eventually resulted in new legal arrangements. Moreover, spouses had some leeway to bequeath property to each other and also to divide specific parts of their property (mostly money and movables) among friends, servants, religious houses or charitable institutions. They did so in their last wills, but also in direct legal arrangements often long prior to their death (Lentze Citation1952/53; Signori Citation2001; Pajcic Citation2013, 320–404).

Such complex economic and legal arrangements with various religious institutions answered to the spiritually most basic hope of individual people for salvation through religious specialists’ prayers. Hence kin groups needed to ensure that ecclesiastic institutions had sufficient financial means to fulfil this task. Affluent elite members and their kin thus invested in particular religious communities to guarantee the material provision necessary for perpetual prayers. Yet memorial provision was considered even more sustainable if assumed by particularly trustworthy monks and nuns – ideally a donator’s own relatives. Families thereby invested both in religious institutions and in specific members who also were their relatives (cf. Signori Citation2021). Monasteries with a long tradition and an equally well-established economic base were often located in the countryside. Hence, alongside their inner-urban ties, this type of arrangement was suited to enhancing connections between urban elites like the Poll family and their rural in-laws (Lutter Citation2021). In the next two chapters we will give examples of this type of familial and economic arrangement, focusing first on a central urban and then on a rural religious institution that both catered to the Polls’ spiritual needs.

Vienna’s town hall chapel – a family business?

Religious communities in urban space provided attractive sites of spiritual attachment and economic arrangements for urban kin groups like the Poll family. Around 1300, Vienna’s ecclesiastic topography included several parish churches and more than a dozen religious communities for monks, nuns and clerics. Among them were Benedictines and Augustinian canons/canonesses, Cistercians and Mendicants. Many of them were founded by the Babenberg, and subsequently by Habsburg dukes, and all were supported by them. Together with the hospitals and pilgrim houses established by the commune, and chapels, often built on individual burghers’ initiatives, Vienna’s ecclesiastical institutions added up to about 50 sanctuaries (Perger and Brauneis Citation1979; Lutter Citation2021).

One of the most prominent chapels that merged spiritual tasks, family interests, and later also an official communal role, was the town hall chapel. Originally founded by the Haimon family as a private chapel, it was ecclesiastically subordinate to Vienna’s main parish church of St Stephen but was exempted from its mother church’s jurisdiction in 1301. Only a decade later (1316) the Habsburg dukes bestowed the chapel on the town council after having put down a revolt in which the Haimon family had participated (Csendes and Opll Citation2001, 117). In 1342, the same year in which the house next to the chapel was eventually established as the city’s town hall (Scheutz Citation2015, 345), Stephan Poll’s son Jakob (cf. ) became vicar of the now official town hall chapel, and soon his brothers, sisters, cousins, and their spouses began to abundantly invest in this institution. Dozens of legal transactions bear witness to how, by donating assets in return for perpetual prayers for their souls, they participated in establishing the chapel’s robust and constantly widening material base.Footnote6 Their support carried on during Jakob’s tenure as vicar over the following forty years until his death sometime after 25 June 1379, when he is mentioned in a charter for the last time (QGStW II/1: n. 929).

From the late 13th century onwards the chapel had already received episcopal privileges, among them several lavishly illustrated letters of indulgence (Perger Citation1972). Such letters granted pilgrims and local worshippers pardons for their sins in return for visiting the privileged church during a period of mostly forty days. Hence ecclesiastical institutions profited from such indulgences, as visitors frequently gave gifts, bought votive offerings or left donations. Likewise, in obtaining letters of indulgence from high ecclesiastical dignitaries for ‘their own’ churches and chapels, influential burghers and their kin used these institutions both for their spiritual well-being and for sustaining family members. Conversely, they made use of their social and political networks to support their churches and chapels.

Jakob Poll’s custodianship of the town hall chapel provides an excellent case in point for these intertwined spiritual and social practices. Throughout the 14th century almost every legal document involving the town hall chapel as a partner – endowments, last wills, as well as property transactions in return for celebrations of masses for the donators’ eternal memories – was either issued by or addressed to at least one member of the Poll family. This impressively underlines the close ties between Jakob Poll as the chapel’s vicar, his wider kin and this ecclesiastical institution. The chapel as a memorial site represented a specific asset for the Poll family: as the town council from 1316 onwards had the official function of being the chapel’s patron – hence its name – both institutions reinforced each other’s institutional continuity and thus reliability. The Polls, in turn, regularly had family members and representatives of their wider kin group sitting on the town council. Probably not least through their membership and being run by the vicar Jakob Poll, the town hall chapel became a regular meeting place of the city council, where its members would consult and decide while also demonstrating their social status. In the 16th century the chapel was the site where new burghers had to swear their oath to the commune (Scheutz Citation2015, 350).

Familial endowment patterns

In 1351, Jakob Poll’s patrilateral first cousin (Vetter) Berthold, who himself owned a little private chapel located in his house, donated a vineyard and some rents to the town hall chapel.Footnote7 Berthold assigned both Jakob in his official function as the chapel’s vicar and other Poll relatives as executors of his last will. Jakob’s further provisions on behalf of his cousin’s will show his considerable range of action due to his multiple roles at the interface of familial, ecclesiastical and communal responsibilities: he resold the vineyard bestowed on the chapel by Berthold to his own brother Ulrich and his first wife Katharina, and invested the money from the assigned rents in an eternal anniversary for his cousin. This means that the chapel’s clerics were obliged to pray for Berthold on each anniversary of his death. In 1368, moreover, Jakob received the former dowry of Berthold’s second wife Katharina and converted it into an endowment to be spent for prayers on behalf of their daughter Ursula and her husband Jans of Haslau. In the same year the couple enlarged this endowment with additional possessions.Footnote8

Further donations by family members follow a broadly similar scheme. Stephan II’s and Jakob’s in-laws bestowed both landed property and money upon the chapel and gave Jakob the explicit permission to invest the endowment capital for the benefit of their personal commemoration.Footnote9 In his function as the chapel’s vicar Jakob used these assets together with his own property both to redeem rents on the sanctuary’s possessions and to invest in new profitable properties and revenues. Hence, during the 1350s and 1360s, the physical structure of the chapel was considerably extended. Jakob’s own last will names relatives and ‘friends’ (a term regularly used for consanguines and in-laws) who had supported him with their advice in augmenting the chapel’s wealth. Likewise, he could rely on the bishop of Passau and his judicial vicar in Vienna, who regularly confirmed and even sealed legal transactions on behalf of the chapel and also served as advisors in the chaplain’s financial operations.Footnote10

Hence marriage arrangements, inheritance and last wills, together with a wide range of further legal transactions involving real estate, rents and money received through pious donations, overlapped significantly to the mutual benefit of the Poll family, the town hall chapel, and the town council’s members, who related to each other in a triangular manner. A good example is the will (1356) of Anna, Ulrich Poll’s second wife: after her parents’ inheritance had been divided between her and her two brothers, Anna – due to her childlessness – chose her husband Ulrich as her sole heir. She decided that of all her possessions only one single asset should be given to Jans, Ulrich’s son from his first marriage. However, this bequest was bound to the condition that Jans married Anna’s niece. If he refused, Jans would have only been able to profit from the asset by way of a life annuity (Leibgeding), while the property itself was to be handed over to the town hall chapel upon his death. Anna also directly assigned some revenues to the town hall chapel in return for an eternal anniversary on her own behalf, which Ulrich was to administer. She thus explicitly based her own commemoration on the future cooperation between her husband Ulrich and her brother-in-law Jakob, the chapel’s vicar. One year later, Ulrich enlarged the material base of her donation. Likewise, Niklas Poll, simultaneously Ulrich’s brother-in-law and son-in-law, and his wife Katharina donated an eternal mass on Anna’s behalf. In addition, Anna’s father, Ortolf Pettziechen, followed his daughter’s lead and bequeathed the enormous sum of 110 pounds to the chapel: it was dedicated to the memory of his entire family and to be safeguarded either by the oldest of his descendants or by the city council. In 1379, Anna’s brothers added to the existing donations, while the chaplain, Jakob, himself actively participated in bearing the expenses for these anniversaries.Footnote11

A register from 1367 listing the chapel’s total possessions impressively shows the involvement of the Poll family and their wider kindred with the sanctuary. Family members – most of them in-laws – donated the entirety of the ‘perpetual’ masses to be held at the chapel’s various altars. Although the list names only one benefactor per donation, other charters show that it was mostly spouses who were responsible for these benefactions. A prominent example of the complex bilateral and inter-generational memorial arrangements, including the living and the dead, is the last will of Leonhard Poll, issued in 1376. He was another of Jakob Poll’s cousins who – upon consultation with his wife Elisabeth – bestowed considerable means on the town hall chapel for an anniversary on behalf of his deceased parents, sister and her late husband Jans Smausser. To this the couple added an anniversary on its own behalf.Footnote12

Although the Polls and their in-laws concentrated their benefactions on the town hall chapel, the probably childless Leonhard had sufficient resources to support several Viennese sanctuaries and also monasteries in the town’s vicinity, as we will show in what follows. Among them the parish church of St Stephen features most prominently, and likewise the private Poll chapel dedicated to the saints Philip and James, whose chaplain at least for some time was a Poll family member. Hence, while the family’s bilateral memory management and social network centred on the town hall chapel, it was simultaneously backed up by provisions for other sanctuaries, not least to guarantee the succession of office-holders needed for the long-term administration of the donated goods. The range of personal relations based on consanguines and in-laws featured clear overlaps with Vienna’s main political peer groups, as represented in the town council. This was extended by explicitly providing for clerical personnel: Jakob Poll himself donated both to St Stephen’s and bestowed his own movable property on his clerical colleagues at the town hall chapel. This was a way both to recruit new personnel and to widen the range of potential benefactors. It is thus not surprising that most of the legal documents discussed above included provisions for boys designated to become priests in the chapel and thus potential successors to Jakob and in future charge of the Polls’ endowments.Footnote13

The Poll family’s urban-rural relations

The close interplay between practices of property distribution, kinship organization and support for religious institutions is most obvious in cases when a family member held an office in such an institution, like the town hall chaplain Jakob Poll. Yet the phenomenon was more widespread among Vienna’s affluent burghers. Basically, both consanguines and in-laws had an equal share in supporting churches and chapels, but also monasteries and – importantly – their family members who lived in these institutions. The latter type of support was based on arrangements comparable to those we have just encountered in previous examples. However, as only men were allowed to serve as priests, it was monasteries and charitable institutions that opened a route for an active participation of female family members in religious communities, while other strands of the ecclesiastic hierarchy were closed to them.

Again, Leonhard Poll’s will (1376) provides a starting point to exemplify how different family branches collaborating as a kin group systematically made use of a set of familial, economic and specific religious strategies to support their consanguines and in-laws in religious institutions that were at the same time important centres of a family’s liturgical remembrance. The following case study will illustrate how late medieval Viennese elites with landed property across the Austrian Danube region sustained and extended relationships between their urban and rural home bases. Among other strategies they did so by means of their daughters and sons who lived and fulfilled their spiritual tasks both in urban religious communities and in rural monasteries, depending on the focus and spread of their families’ social and economic activities (Frey and Krammer Citation2019).

Leonhard Poll is never mentioned as an office-holder among Vienna’s political core elite, represented by members of the inner town council as documented from around the mid-14th century onwards. Nevertheless, he owned a large number of estates inside and outside the city. His landed property included at least seven houses in Vienna and 29 commercially used sites, such as farmyards, vineyards and other possessions in the city and its environs (Sailer Citation1931). Probably childless at the end of his life, he and his wife Elisabeth had a lot of possessions to distribute in their will. Besides several churches, chapels and monasteries within the city of Vienna, Leonhard and Elisabeth also individually supported two of their female relatives, who were nuns in St Bernhard, a Cistercian nunnery some 80 km north-west of Vienna (Frey and Krammer Citation2019). Each of the two nuns were to receive regular revenues from a vineyard and a sum of ten Viennese pounds. Both are addressed as Muhme – a term that mostly referred to aunts and grandaunts but could likewise be used for female cousins. It was used to signify kin relations that went beyond the inner circle of spouses and their progeny, often indicating lateral relatives.

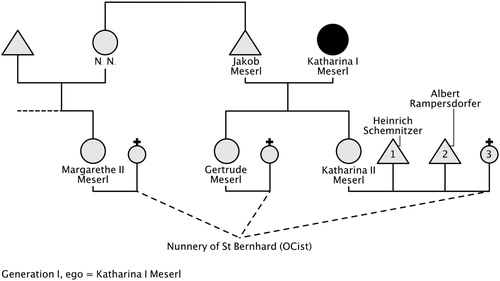

The first nun Leonhard refers to as his Muhme is further addressed by her last name, Meserlin, and thus identified as a female member of the Meserl family, who were then members of Vienna’s town council. Leonhard’s second Muhme went by the first name of Katharina. Although there is no direct evidence of the specific kin relation between the two Muhmen in the nunnery, Katharina was probably also a member of the Meserl family, named after her mother, Katharina I, who was married to Jakob Meserl. Jakob held urban offices in Vienna at least in 1340, 1341 and 1352. He was closely connected to members of the Poll family, with whom, on account of their political authority, he corroborated legal documents on a regular basis.Footnote14

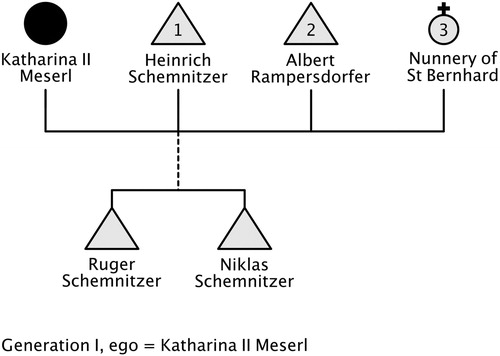

Jakob and Katharina Meserl I had at least two daughters, Katharina II and Gertrude. The latter is already mentioned as a nun in St Bernhard’s in 1328, when her parents assigned rents from a house to her. By contrast, Katharina II had first married the influential Viennese burgher Heinrich Schemnitzer, who died in 1340. Her second husband was the burgher Albert Rampersdorfer, who lived until 1375 (Sailer Citation1931, 363). It is only one year later (1376) that a nun named Katharina appears in Leonhard Poll’s will, and thus it is plausible that, after her second husband’s death, Katharina Meserl II decided to re-orientate her life in the nunnery of St Bernhard. Her family had long before established material and personal ties to the convent. Katharina’s sister Gertrude already lived there as well as her cousin Margarethe, a daughter of one of Jakob Meserl’s otherwise unknown sisters. In 1349 Jakob provided Margarethe with revenues (Zeibig Citation1853, 298). Thus the spouses Jakob and Katharina I gave shares of their own possessions to both their daughters and their niece, who all then lived in St Bernhard’s. All these revenues were intended to fall to the monastery’s property after the nuns’ deaths ().

This type of arrangement between the Poll and Meserl families built on relations established for decades. A letter of indulgence from 1325 issued by a Rome-based bishop, in which Jakob Meserl obtained a 40 days’ indulgence for the Polls’ Viennese house chapel of the saints Philip and James, is significant. This probably provided the Polls with considerable profit, as indulgences invited pilgrims and local worshippers to visit the chapel and give donations in return for pardon for their sins. Almost fifty years later (1371), Leonhard Poll and his wife Elisabeth themselves donated a mass to the same chapel, thus illustrating the continuity of the same mechanism that tied them to the Polls via the spiritual anchor of their house chapel, which was then a key site of the Polls’ liturgical memory (QGStW II/1: nos. 94 and 798). The sequence of acts already suggests the families’ tight links in the previous generation, as the still young Jakob Meserl supported the Poll family’s chapel through his connections to a high church dignitary at a time, when the Polls’ investment in the town hall chapel had not yet got under way.

Alongside targeted marital and property arrangements and the maintenance of kin groups’ liturgical memory, specific legal functions could be delegated through bonds of kin. They systematically included blood and lateral relatives and provided further means to sustain trustful bonds between them. For instance, in 1370 the brothers Ruger and Niklas Schemnitzer sold two vineyards they had inherited from their parents to Leonhard Poll for the huge sum of 332 Viennese pounds (QGStW II/1: n. 775). As we have seen, the Schemnitzers were related to both the Meserls and the Polls through the first marriage of Katharina Meserl II – Leonhard Poll’s Muhme and subsequently a nun in St Bernhard’s – with Heinrich Schemnitzer. Heinrich had at least two sons, Ruger and Niklas, either with Katharina or from a previous marriage.Footnote15 In 1370, following up on this substantial purchase from his nephews, Leonhard Poll used his will to reinvest the Schemnitzers’ inheritance in the kin group’s wider circulation of goods, and assigned one of the two vineyards to his Muhmen in St Bernhard’s. He also nominated Niklas Schemnitzer as a trustee to secure the cultivation of the vineyard thus providing him further access to his former property. Hence, this part of the Schemnitzers’ inheritance went back to their family, as both Meserl daughters were then nuns in St Bernhard´s and one of them, Katharina II, was either Ruger’s and Niklas’ mother or step-mother. In addition – together with Leonhard’s uncle (Oheim) Jakob Poll and the mayor of Vienna – Niklas Schemnitzer was appointed as executor of Leonhard’s and Elisabeth’s last will.

To sum up, the Poll and Meserl couples both provided family members inside St Bernhard’s with assets or rents from their possessions. Likewise, property devolution could be extended to in-laws, as in the case of Leonhard and Elisabeth Poll who passed on revenues from family property on to aunts/cousins on the Meserl side of their kin. Probably lacking any children of their own, they invested in monastery-based female in-laws of the next generation and thus at the same time corroborated the wider family’s ties to the community of St Bernhard entitled to pray for them (cf. Signori Citation2021). Such alliances based on bilateral kin relations merged different family branches into endogamous kin groups, simultaneously preserving major parts of their property across generations instead of dividing it up by individual inheritance. In turn, members of these groups used their bilateral ties to exchange and thus accumulate properties and other economic resources. Hence bilateral kinship relations provided prime channels for the circulation of goods that was grounded in a spiritual economy anchored in religious communities like St Bernhard’s as hubs for this circulation ().

Interregional mechanisms of kinship, gender and memory

In her study of kin relations among Vienna’s town council members, Elisabeth Gruber established that by the mid-14th century the Poll family had moved into the centre of the city’s web of social elites (Gruber Citation2013, 32–35). As we have demonstrated above, the town hall chapel became part of their ‘family business’. Together with other religious institutions it played an important role as a hub in the network of donation strategies that the Polls channelled through their kin both in Vienna and its surroundings. In this final section we will follow a member of this top elite family who moved away from his hometown in the course of the 14th century. Generally, it was rather common for members of influential merchant families either to migrate to neighbouring or to more distant places to extend the scope of family business to new territories and to widen the geographical range of their families’ networks (Kubinyi Citation1978; Perger Citation1993). Such a move could also positively affect the migrant’s social mobility. Hence these were often less prominent family members, who by means of advantageous marriage arrangements would soon establish a considerable social status in their new home towns and consequently add a new branch to their kin (Majorossy and Sarkadi Nagy Citation2019).

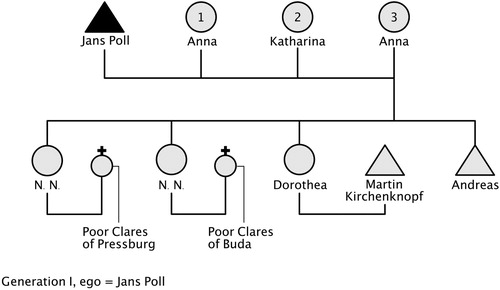

However, our next protagonist, Jans Poll, belonged to the most prominent branch of his family and, like his father, was an influential burgher in Vienna before he moved some 80 km eastwards to Pressburg on the border of the neighbouring Kingdom of Hungary. He was most probably the son of Ulrich Poll II, chaplain Jakob Poll’s brother, who were both grandchildren of the first traceable member of the family, Konrad Poll. This is one of the rare cases where a 14th-century family can be traced back over four generations.Footnote16 As a wealthy Viennese merchant, Jans was involved in short- and long-distance trade in Flemish, German and Italian cloth, but also had an interest in Styrian iron. His kin were among the richest and most influential Viennese cloth-merchant families. His father’s first cousin, Berthold I and his son, Berthold II owned shops on the Tuchlauben – Vienna’s prominent cloth-sellers’ site near the High Market (Hoher Markt) and the town hall. Jans’ last will also testifies to his contacts with top elite families in Villach (Carinthia), who were involved in iron production and trade. The bishop of Carinthian Gurk may have also been among his clients (Skorka Citation2018, 352). On the whole, Jans Poll’s profile fits well into a broader pattern of kin-related economic strategies that linked Viennese elite families to Southern Germany, via Styria and Carinthia to Venice and also to the Kingdom of Hungary – mainly to Buda and Pressburg. During the 15th century, additional towns such as Wiener Neustadt were included in these regional elite families’ strategic networks (Majorossy and Sarkadi Nagy Citation2019).

During the 1340s and 1350s Jans Poll held several commissions of trust, such as witness of legal transactions in Vienna and executor of last wills. As shown above, his wider family had close ties to noble families around the city. Jans married at least twice in Vienna: Anna is documented as his wife between 1343 and 1355, Katharina only once as of 1357. Unfortunately, the Viennese sources neither reveal anything about his wives’ families of origin nor if the couples left any children.Footnote17 Around 1350 at the latest, he started trading in Venice together with Nuremberg merchants (Simonsfeld Citation[1887] 1968, II/51–52). Through these business connections, his kin network later stretched to the court of the Hungarian King Louis of Anjou (d. 1382) in Buda. Jans’ Vetter, Ott Poll, supposedly died in Buda in the late 1370s (Skorka Citation2018, 344, 350). Jans and his kin were so successful in utilizing the economic potential of the Hungarian market to the benefit of royal circles that in 1360 King Louis informed the Venetian authorities that ‘the former burgher of Vienna’ Jans Poll had become a Hungarian ‘citizen’. The king thus took him under his special protection and provided him all the rights of an inhabitant of the Kingdom of Hungary. However, Jans did not subsequently move to the royal residence Buda, but became a burgher of Pressburg, located much closer to his kin in Vienna.Footnote18

From this time on, Jans quickly adapted to Pressburg’s local political elite, despite the fact that only a few families shared the town leadership among each other and formed a closed circle. As elsewhere in the region and contrasting Italian patricians, leading families in Hungarian towns mostly changed after two or three generations. However, most of these influential burghers bore nobility-related titles like ‘count’ (comes) and were ‘the king’s friends’ (familiares) due to their services to the royal family (Majorossy Citation2013, 116–119). Jans Poll thus established kin relations with Albert Hamboth, whose kin group was one of the most powerful in early 14th-century Pressburg. He became a business partner of the town judge, comes Jakob, and was involved in trading Hungarian wine. After having moved to Pressburg in 1360 (Skorka Citation2018, 347), he bought several houses there, first in the suburbs – seven on Hochstrasse and Pechkengasse in 1364, and an eighth one in 1368 – and later also in the city centre (1374), as well as a shambles at the St Lawrence gate (1370). Simultaneously, Viennese sources document incomes from his houses and properties there, which testify to his dual base.Footnote19

Hungarian sources give some additional information on Poll family members. In Pressburg, where Jans Poll had probably arrived already as a widower, he soon married for a third time: his wife Anna outlived him for many years and died some time before 18 May 1407 (AMB: n. 753). Like his Viennese relatives, Jans included both his progeny and religious institutions in his broad portfolio of career, kin and property management most powerfully represented in his last will of 1375 (AMB: n. 327). Already written in Jans’ new residence town, it mentions one son, Andreas, who perhaps originated from one of the Viennese marriages, since he was still living there in 1372 (Sailer Citation1931, 211), but he was the one who inherited his father’s town house in Pressburg. Jans’ daughter Dorothea married Martin Kirchenknopf from Pressburg. Martin had a relative named Hans, who in the 1360s served as chaplain in the Vienna castle’s chapel. Two other daughters entered houses of the Poor Clares in Pressburg and in Buda.Footnote20 On entry, each of them received 100 red guldens as a ‘dowry’. Hence, while reinforcing existing ties through in-laws, at each new site of the Polls’ family business their daughters served as intercessors in one prominent house of the mendicant orders, which were particularly fostered by the Anjou family and thus consolidated Jans Poll’s ties with the royal court (Burkhardt Citation2015; Just and Jaspert Citation2019). Surviving charters document some of his and his third wife’s additional bequests (AMB: nos. 175 and 327). Shortly before her own death, in 1407 Anna bequeathed to a perpetual mass foundation for her family established earlier at Pressburg’s main parish church of St Martin. Jans’ Vetter, Ulrich, stepson of the Pressburg town councillor Friedrich Habersdorfer, took care of the foundation on behalf of the Polls (AMB: n. 753). This arrangement testifies to their successful establishment within the socio-political and kinship network at their new dwelling place and beyond their lifetime ().

Donator’s choice

Jans Poll was the first burgher who gave a substantial donation to the local ‘burghers’ brotherhood, later known as the Corpus Christi confraternity, for the building of a chapel and altar in the parish church of St Martin. Established in 1349, most probably by the canons of the Pressburg Chapter, later documents testify that by the end of the 14th century this clerical confraternity had turned into a brotherhood representing the ruling urban elites. It became the richest confraternity, dominating the urban laity’s religious life throughout the whole of the 15th century (Majorossy Citation2018, 468–473). Jans gave a hundred red guldens for its roof tiles and for its glass window – as much as for the dowry for each of his daughters who went to Poor Clare houses. Confraternities held lists of their members, mostly naming husbands and wives together. Some widows retained their membership after their husbands’ death and were then listed individually (Majorossy Citation2021). Confraternity membership provided both ‘ritual kinship’ (Terpstra Citation2000) and offered convenient opportunities for establishing and sustaining social ties, often by means of marriage among members. Consequently, economic investments in the confraternity linked to spiritual purposes would add to a long-term remembrance of the benefactors, not just by their kin but also by extended groups of peers.

Importantly, in his choice of benefactions Jans Poll followed the example of prominent Pressburg elite members: he contributed to an altar foundation in St Martin’s parish church dedicated to the Holy Virgin, established in the early 14th century by a former judge, comes Hertlinus. Similar foundations had been established by Jans’ Pressburg peers, with whom he entered into family and business relations upon his arrival in town: Albert Hamboth was responsible for the oldest known foundation in town (1307) dedicated to the altar of the Holy Virgin and several other saints; Jakob the Judge for an altar foundation (before 1349) dedicated to the saints Adalbert and George (Majorossy Citation2021: Appendix 3). Hamboth’s family ties and his altar dedications show strong connections to Vienna. Hamboth’s wife, Margaretha was the sister of an Augustinian canon in the nearby town of St Pölten and widow of the Viennese Leopold auf der Säul (Perger Citation1967/1969, 72). In 1347, she donated to Vienna’s civic hospital (Bürgerspital) for her own and her husband’s soul. The document itself was sealed by Michael, a Viennese member of the Poll family (Pohl-Resl Citation1996; Csendes Citation2018, 54).

At the same time, Jans kept up the same strategy to select sites for benefaction according to his kin’s preferences back in his hometown. He supported the civic hospital (Csendes Citation2018, 98 and 108), and likewise donated to St Martin’s altar in Vienna’s main parish church of St Stephen. In 1447, almost a century later, a specific ‘Hans Poll mass’ was still being performed at the same altar (QGStW I/2: n. 1673, QGStW II/2: n. 3208). Given the status of Vienna’s town hall chapel as a ‘family business’ with Jans’ uncle Jakob as its chaplain, it is not surprising that the chapel was the only Viennese institutional beneficiary named in his Pressburg will. What is more, it occupied the most prominent place among all provisions. Among other things Jans left 50 Viennese pounds for the chapel’s glass windows alone (AMB: n. 327).

In sum, Jans’ pious donations show several structural similarities that connect his main sites of residence, Vienna and Pressburg. First, his mass donations in both towns were targeted at altars with the same patronage, St Martin. Both altars were located in the towns’ most prominent parish churches. Second, the cult of the Holy Virgin features in many of his bequests: he donated glass windows for the Our Lady town hall chapel in Vienna, and the Pressburg mass foundation was related to the feast of the Conception of the Virgin. He also donated ten pounds to the Our Lady Franciscan friary in Pressburg. Third, he supported the urban hospitals in both towns – the Bürgerspital in Vienna, and both suburban hospitals in Pressburg. Fourth, comparable to Hungarian royal and Austrian ducal preferences, he donated to the Poor Clares’ houses and sent his daughters there as intercessors and mediators. Finally, this time without a Viennese parallel in Jans Poll’s portfolio, Pressburg’s Corpus Christi confraternity was the target of his most generous testamentary bequest.

Conclusion

This final example is representative of social practices that became common during the 15th century and reached a peak during the Counter-Reformation in the Habsburg lands (Majorossy Citation2018). Confraternities emerged as important players in urban space and, like the religious communities previously discussed, helped to establish and corroborate ties between representatives of kin groups who held or moved into key positions in political organization. Hence they were intricately tied in with urban communal organization and the establishment of ruling elites. Outstanding elite representatives like the Polls, but also middling groups, operated on various local, regional and trans-regional levels. The scope of their actions depended on a large set of elements: their property and political standing, their success as merchants and their proximity to princely rulers, their longevity and the range of their social contacts, including bilateral kin networks as well as their strategic investment and uses of large and smaller assets in various segments of the urban, regional and ecclesiastical markets. Within this set of factors, the ‘spiritual economy’ was a very serious business, documented by the detailed arrangements for celebrating eternal masses on behalf of individual benefactor’s souls (Pohl-Resl Citation1996; Majorossy Citation2021). Top elites like the Polls had large and mixed portfolios (Lutter Citation2021) and would provide religious houses with extraordinary amounts of real estate, money, liturgical objects and other goods in return for abundant anniversaries. Family members of both genders played a key role in corroborating ties to religious institutions not just as benefactors, but also as community members, where they were expected to ensure that family investments would be properly, i.e. ‘perpetually’, taken care of by masses and communal prayer.

Hence not just in urban communities but particularly visible there, material and spiritual assets were two sides of the same coin. They provided a wide range of resources drawn upon by individuals and kin groups in an astonishingly wide variety. Marriage politics of regional elite families largely followed isogamous patterns that enhanced bonds between council members and other office holders. Intermarriages of in-laws were effective means to consolidate a robust power base within and across towns as well as with their rural hinterland. Marriages within and across status groups show that social mobility was quite substantial before 1500, which makes it difficult even to establish clear-cut social strata.Footnote21 The most wealthy and influential families succeeded in establishing both hypergamous and hypogamous marital relations that connected them with important noble office holders of the ducal or royal courts in the Austrian lands and the Kingdom of Hungary, and mutually fostered corresponding ties based on business and foundation practices. Hence, while organizing and maintaining social and spiritual memories were among the most important tasks of religious institutions, complex arrangements of property devolution among bilateral kin groups were all at the same time among the most important channels to allocate and distribute the resources needed for maintaining those memories. Neither religious communities nor kin groups fulfilled these tasks alone. On the contrary, one key for a sustainable spiritual economy was the overlap of these communities brought about by actors and goods belonging to both of them, interacting within and moving between them.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for feedback and comments to Andre Gingrich, Bernhard Jussen, Margareth Lanzinger and Gabriela Signori.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Jussen Citation2013, cf., Mitterauer Citation2003; for the broader debate among historians about Goody’s approach, see e.g. the special issue of Continuity and Change (1991); for a good recent summary of this debate with more up to date bibliographical references see Mathieu Citation2018. Jack Goody’s conceptual framework to analyse patterns of kinship and marriage as key elements of social organization deeply interwoven with political, economic and religious fields still provides important methodological tools to overcome meta-categories of structural thought and binary terms for framing them, cf. esp. Segalen Citation2021.

2 In the following, today’s geographical names Budapest and Bratislava are given in their contemporary forms, i.e. Buda and Pressburg respectively. Studies on the topics discussed in this article covering the Central European towns mentioned include Signori Citation2011; Gruber Citation2013; Lutter Citation2021; Majorossy Citation2021; Rolker Citation2014; Teuscher Citation2007.

3 The term was first coined by Max Weber in his book on Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Weber Citation[1905] 2005). While Weber recognized the idea of ‘accountability’ in medieval ‘Catholic’ practices of penitence and redemption, he did not link this idea to economic thinking in a narrower profit-oriented sense. According to Weber, the divide between religiously and economically motivated social practices was utterly modern and connected to the rise of Protestantism. His approach was criticized in several respects (cf. A. Giddens in his introduction to the English translation of the book, Citation[1905] 2005). Contrary to Weber, we argue in this paper that Catholic city dwellers were perfectly able to distinguish between moral and economic motives, yet they did so in a way that made these motives appear two sides of the same coin (cf. Chiffoleau Citation[1980] 2011, see also Signori Citation2021). For recent and comparable uses of the concept in social anthropology cf. D. Rudnyckj´s book on efforts in contemporary Indonesia to reconcile Muslim virtues with the principles of a global market economy. Rudnyckj addresses spiritual economy as a reconfiguration of faith and economy ‘in which religious values are mobilized to address […] the move toward transnational economic integration.’

4 This Jakob Poll is not to be confused with the prominent family member and chaplain Jakob Poll, who will be introduced later. This marriage arrangement is documented in QGStW II/1, nn. 527, 830. It is a case in point that would have required a dispensation by ecclesiastical authorities from the canonical rules of marriage degree. However, respective legal documentation is still rare at the time and has not survived in this case (Rudnyckyj Citation2010).

5 Medieval inheritance law is particularly complicated, because it was regionally oriented and thus subject to numerous variations; for a good recent overview on medieval Europe see Gottschalk Citation2013; for Vienna see Lentze Citation1952/53; Demelius Citation1970.

6 All documented in QGStW, online at www.monasterium.at

7 QGStW II/1, n. 385. Contemporary kin terminology reflects the openness of bilateral relations: the middle-high German term Vetter may refer to any male cousin (regardless of whether he is on the maternal or paternal side), but it also can address a more distant, not further specified male relative of the same generation. The corresponding term for female relatives covering the same range of relations is Muhme (cf. below, next section).

8 These transactions are documented in QGStW II/1, nn. 295, 719, 741. The Haslau were one of the politically most influential noble families in the Duchy of Austria, cf. Frey and Krammer Citation2019, 392–94, and 399.

9 Stephan II himself donated at least twice to the chapel: QGStW II/1, nn. 411, 903; further benefits by in-laws are documented in QGStW II/1, nn. 339, 962; 690.

10 In-laws: QGStW II/1, n. 765; bishop: QGStW II/1, nn. 333, 362, 479, 492, 493, 595, 680, 683, 709, 713, 793, 901–903, 929, 951, 953, 954.

11 Transactions in QGStW II/1, nn. 485, 487, 505, 682, 790, 964.

12 The register for 1367 has survived in the collection of charters of the Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna; other transactions in QGStW II/1, nn. 706; 568; 798, 889, 929.

13 QGStW II/1, nn. 364, 475, 793; on Jakob Poll’s own provisions see QGStW II/1, n. 765.

14 E.g. QGStW II/5, n. 47. Jakob Meserl was head of Vienna’s civic hospital (QGStW II/1, nn. 83, 224); Niklas Meserl, probably a brother of Jakob, was the city’s judge (QGStW II/1, n. 207).

15 Often, charters do explicitly spell out only some aspects of the relations between people involved in legal transactions. Further information has to be deduced from mostly fragmentary data given by various documents: Katharina Meserl II is mentioned for the first time in 1333, whereas Heinrich Schemnitzer is referred to for the first time in 1317 and for the last time in 1340. It thus seems that the spouses' age difference was large, and their marriage short (Sailer Citation1931, 391f).

16 Leopold Sailer (Citation1931, 216) lists four different members of the Poll family with the name Jans (Jans Poll I, II, III, IV). However, a re-reading of the charters suggests that there were only two and the references actually refer to Jans Poll I and his nephew, Jans Poll II (and the latter was the one who moved to Pressburg).

17 For his activity as witness: QGStW II/1, nn. 380, 426, 468; Csendes Citation2018, 48, 75. For his wives in Vienna: QGStW II/1, nn. 261, 380, 681 (Anna); QGStW II/1, nn. 467, 502; I/10, n. 17914 (Kathrein).

18 Ljubić Citation1874, 31: Hungarian citizenship; QGStW I/8, n. 15823: special protection; cf. Majorossy Citation2021; Skorka Citation2018.

19 Sources on purchases in Pressburg: AMB, nn. 216, 256 (Hochstrasse, Pechkengasse), n. 323 (Judenhof), n. 276 (St Lawrence gate). Viennese houses during his time in Pressburg: Münzerstrasse,1374, vor Stubentor under den Ledreren, 1372, in Antiquo Foro, 1374, domo sita in acie, 1375: QGStW II/1, n. 840; I/3, n. 3305; III/1, n. 620; III/3, n. 3170; III/2, n. 2090.

20 QGStW II/1, n. 600; Melk Stiftsarchiv, Urkunden, 15.6.1395; daughters: AMB, n. 327.

21 For contrasting marriage patterns in South Arabia after 1250 see Gingrich et al., Citation2021 in this issue.

References

- AMB = Archiv mesta Bratislavy (Town Archives of Pressburg/Bratislava), Bratislava.

- QGStW = Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Wien (Sources on the History of the City of Vienna).

- Algazi, G. 2010. “Bringing Kinship (Back) in”. Mediterranean Historical Review 25 (1): 83–92.

- Bonfield, L. 1991. “Canon Law and Family Law in Medieval Western Christendom.” Continuity and Change 6 (3): 361–374.

- Borgolte, M., et al., ed. 2014–2017. Enzyklopädie des Stiftungswesens in mittelalterlichen Gesellschaften. 3 vols. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Burkhardt, J. 2015. “Allerchristlichste Könige und Mindere Brüder: Franziskanische Klöster als Begegnungsräume im angevinischen Königreich Ungarn.” In Abrahams Erbe: Konkurrenz: Konflikt und Koexistenz der Religionen im europäischen Mittelalter, edited by K. Oschema et al., 340–357. Munich: De Gruyter.

- Chiffoleau, J. [1980] 2011. La comptabilité de l’au-delà: les hommes, la mort et la religion dans la région d’Avignon à la fin du Moyen Âge (vers 1320–vers 1480): Paris: Albin Michel.

- Clarke, H., and A. Simms, eds. 2015. Lords and Towns in Medieval Europe. The European Historic Towns Atlas Project. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Csendes, P., ed. 1986. Die Rechtsquellen der Stadt Wien. Vienna: Böhlau.

- Csendes, P., ed. 2018. Regesten der Urkunden aus dem Archiv des Wiener Bürgerspitals 1257–1400. Innsbruck-Vienna-Bolzano: StudienVerlag.

- Csendes, P., and F. Opll, eds. 2001. Wien. Geschichte einer Stadt. Vol. 1: Von den Anfängen bis zur Ersten Wiener Türkenbelagerung (1529). Vienna: Böhlau.

- Demelius, H. 1970. “Ehegüterrecht der Münzerstraße im 15. Jahrhundert.” Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 26: 46–75.

- Duindam, J. 2021. “Gender, Succession and Dynastic Rule.” History & Anthropology 32 (2): 151–170.

- Frey, D., and H. Krammer. 2019. “Ein Frauenkloster und seine sozialen Beziehungsgeflechte in städtischen und ländlichen Räumen: Die Zisterzienserinnen von St. Niklas bei Wien im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert.” In Orden und Stadt: Orden und ihre Wohltäter, edited by J. M. Havlík, J. Hlaváčková, and K. Kollermann, 386–422. Prague-St. Pölten: Diözesanarchiv St. Pölten.

- Geuenich, D., and O. G. Oexle, eds. 1994. Memoria in der Gesellschaft des Mittelalters. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Gingrich, A. et al. 2021. “Between Diversity and Hegemony: Transformations of Kinship and Gender Relations in Upper Yemen, Seventh- to Thirteenth Centiry CE.” History & Anthropology 32 (2): 188–210.

- Goody, J. [1983] 2012. The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gottschalk, K. 2013. “Erbe und Recht: Die Übertragung von Eigentum in der Frühen Neuzeit.” In Erbe: Übertragungskonzepte zwischen Natur und Kultur, edited by S. Willer, S. Weigel, and B. Jussen, 85–124. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Gruber, E. 2013. “Wer regiert hier Wien: Handlungsspielräume in der spätmittelalterlichen Residenzstadt Wien.” In Mittler zwischen Herrschaft und Gemeinde: Die Rolle von Funktions- und Führungsgruppen in der mittelalterlichen Urbanisierung Zentraleuropas, edited by E. Gruber, et al., 19–48. Innsbruck: StudienVerlag.

- Gruber, E., et al., ed. 2013. Mittler zwischen Herrschaft und Gemeinde: Die Rolle von Funktions- und Führungsgruppen in der mittelalterlichen Urbanisierung Zentraleuropas. Innsbruck: StudienVerlag.

- Jussen, B. 2013. “Erbe und Verwandtschaft: Kulturen der Übertragung.” In Erbe: Übertragungskonzepte zwischen Natur und Kultur, edited by S. Willer, S. Weigel, and B. Jussen, 37–64. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

- Just, I., and N. Jaspert, eds. 2019. Queens, Princesses and Mendicants. Close Relations in a European Perspective. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

- Korpiola, M., and A. Lahtinen, eds. 2018. Planning for Death: Wills, Inheritance and Property Strategies in Medieval and Reformation Europe. Leiden: Brill.

- Kubinyi, A. 1978. “Die Pemfflinger in Wien und Buda: Ein Beitrag zu wirtschaftlichen und familiären Verbindungen der Bürgerschaft in den beiden Hauptstädten am Ausgang des Mittelalters.” Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 34: 67–88.

- Lentze, H. 1952/53. “Das Wiener Testamentsrecht des Mittelalters.” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte 69: 98–154, and 70: 159–229.

- Ljubić, Š., ed. 1874. Listine o odnašajih izmedju južnoga slavenstva i Mletačke republike [Letters and Charters between the Southern Slavs and the Venetian Republic]. Vol. 4. Zagreb: Fr. Župan.

- Lutter, C. 2017. “The Babenbergs: Frontier March to Principality.” In The Origins of the German Principalities 1100–1350, edited by G. A. Loud, A. V. Murray, and J. Schenk, 312–328. London: Routledge.

- Lutter, C. 2021. “Donators’ Choice? How Benefactors Related to Religious Houses in Medieval Vienna.” In Entscheiden über Religion: Religiöse Optionen und Alternativen im Spätmittelalter und in der Frühen Neuzeit, edited by M. Pohlig and S. Steckel. Tübingen, in press.

- Lynch, K. A., ed. 2003. Individuals, Families, and Communities in Europe, 1200–1800: The Urban Foundations of Western Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Majorossy, J. 2013. “Towns and Nobility in Medieval Western Hungary.” In Mittler zwischen Herrschaft und Gemeinde, Die Rolle von Funktions- und Führungsgruppen in der mittelalterlichen Urbanisierung Zentraleuropas, edited by E. Gruber, et al., 109–150. Innsbruck: StudienVerlag.

- Majorossy, J. 2018. “The Fate and Uses of Medieval Confraternities in the Kingdom of Hungary during the Age of Reformation.” In Bruderschaften als multifunktionale Dienstleister der Frühen Neuzeit in Zentraleuropa, edited by E. Lobenwein, M. Scheutz, and A. S. Weiß, 441–475. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag.

- Majorossy, J. 2021. Piety in Practice: Urban Religious Life and Communities in Late Medieval Pressburg (1400–1530). Budapest: CEU Press, in press.

- Majorossy, J., and E. Sarkadi Nagy. 2019. “Reconstructing Memory: Reconsidering the Origins of a Late Medieval Epitaph from Wiener Neustadt.” Acta Historiae Artium 60 (2019): 71–122.

- Martin, J. 1993. “Zur Anthropologie von Heiratsregeln und Besitzübertragung: 10 Jahre nach den Goody-Thesen.” Historische Anthropologie 1 (1): 149–162.

- Mathieu, J. 2018. “Entwicklung von Ehe und Familie in Europa: Die Jack Goody-Debatte um die christliche Prägung der Familienverfassung.” In Familienvorstellungen im Wandel: Biblische Vielfalt, geschichtliche Entwicklungen, gegenwärtige Herausforderungen, edited by S. Klein, 83–98. Zurich: TVZ Verlag.

- Mitterauer, M. 2003. “Geschichte der Familie: Mittelalter.” In Geschichte der Familie, edited by A. Gestrich, J.-U. Krause, and M. Mitterauer, 160–363. Kröner: Stuttgart.

- Morsel, J. 2014. “Geschlecht versus Konnubium? Der Einsatz von Verwandtschaftsmustern zur Bildung gegenüberstehender Adelsgruppen (Franken, Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts).” Historische Anthropologie 22 (1): 4–44.

- Pajcic, K. 2013. Frauenstimmen in der spätmittelalterlichen Stadt? Testamente von Frauen aus Lüneburg, Hamburg und Wien als soziale Kommunikation. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

- Parkin, R., and L. Stone. 2004. Kinship and Family: An Anthropological Reader. Oxford: Wiley–Blackwell.

- Perger, R. 1967/69. “Die Grundherren im mittelalterlichen Wien. III. Teil.” Jahrbuch des Vereins für Geschichte der Stadt Wien 23/25: 7–102.

- Perger, R. 1972. “Zur Geschichte von St. Salvator.” Wiener Geschichtsblätter 27: 17–28.

- Perger, R., et al. 1980. Wiener Bürgermeister im Spätmittelalter. Vienna: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk.

- Perger, R. 1993. “Beziehungen zwischen Preßburger und Wiener Bürgerfamilien im Mittelalter.” In Städte im Donauraum: Sammelband zum 700 Jahresfeier des Stadtgrundprivilegs von Preßburg 1291–1991, edited by R. Marsina, 149–158. Bratislava: HÙ SAV.

- Perger, R., and W. Brauneis. 1977. Die mittelalterlichen Kirchen und Klöster Wiens. Vienna: Paul Zsolnay Verlag.

- Pohl-Resl, B. 1996. Rechnen mit der Ewigkeit: Das Wiener Bürgerspital im Mittelalter. Vienna: Oldenbourg.

- Rolker, C. 2014. Das Spiel der Namen: Familie, Verwandtschaft und Geschlecht im spätmittelalterlichen Konstanz. Stuttgart: Thorbecke.

- Rudnyckyj, D. 2010. Spiritual Economies: Islam, Globalization, and the Afterlife of Development. London: Cornell University Press.

- Sabean, D., and S. Teuscher. 2007. “Kinship in Europe: A New Approach to Long-Term Development in Kinship in Europe.” In Kinship in Europe. Approaches to Long-Term Development (1300–1900), edited by D. Sabean, J. Mathieu, and S. Teuscher, 1–32. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Sabean, D., S. Teuscher, et al., eds. 2011. Transregional and Transnational Families in Europe and Beyond: Experiences Since the Middle Ages. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Sailer, L. 1931. Die Wiener Ratsbürger des 14. Jahrhunderts. Vienna: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk.

- Scheutz, M. 2015. “In steter Auseinandersetzung mit mächtigen Nachbarn: Das alte und das neue Rathaus.” Wiener Geschichtsblätter 70 (4): 343–363.

- Segalen, M. 2021. “Gender and Inheritance Patterns in Rural Europe: Women as Wives, Widows, Daughters and Sisters.” History & Anthropology 32 (2): 171–187.

- Seidel, K. 2009. Freunde und Verwandte: Soziale Beziehungen in einer spätmittelalterlichen Stadt. Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag.

- Signori, G. 2001. Versorgen – Vererben – Erinnern. Kinder- und familienlose Erblasser in der städtischen Gesellschaft des Spätmittelalters. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Signori, G. 2011. Von der Paradiesehe zur Gütergemeinschaft: Die Ehe in der mittelalterlichen Lebens- und Vorstellungswelt. Frankfurt/Main: Campus.

- Signori, G. 2021. “Community, Society, and Memory in Late Medieval Nunneries.” History & Anthropology 32 (2): 231–248.

- Simonsfeld, H., ed. [1887] 1968. Der Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venedig und die deutsch-venetianischen Handelsbeziehungen: Quellen und Forschungen. 2 vols. [Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung]. Aalen: Scientia Verlag.

- Skorka, R. 2018. “Egy 14. századi vaskereskedő nyomában.” [In the Footsteps of a 14th-Century Iron Merchant]. In Veretek, utak, katonák: Gazdaságtörténeti tanulmányok a magyar középkorról [Plates, Routes, Soldiers: Economic Studies on the Hungarian Middle Ages], edited by B. Weisz, 339–354. Budapest: MTA TTI.

- Spieß, K.-H. 1993. Familie und Verwandtschaft im deutschen Hochadel des Spätmittelalters. 13. bis Anfang des 16. Jahrhunderts. Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Beihefte 111. Stuttgart: Steiner.

- Spieß, K.-H, ed. 2009. Die Familie in der Gesellschaft des Mittelalters. Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke Verlag.

- Terpstra, N., ed. 2000. The Politics of Ritual Kinship: Confraternities and Social Order in Early Modern Italy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Terpstra, N., ed. 2013. Cultures of Charity: Women, Politics, and the Reform of Poor Relief in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Teuscher, S. 2007. “Politics of Kinship in the City of Bern at the End of the Middle Ages.” In Kinship in Europe. Approaches to Long-Term Development (1300-1900), edited by D. Sabean, J. Mathieu, and S. Teuscher, 76–90. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Ubl, K. 2008. Inzestverbot und Gesetzgebung: Die Konstruktion eines Verbrechens (300–1100). Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Weber, M. [1905] 2005. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by T. Parsons, introduced by A. Giddens. London–New York: Routledge, e-Library.

- Zeibig, H., ed. 1853. Das Stiftungs-Buch des Klosters St. Bernhard. Fontes Rerum Austriacarum 2, Vol. 6, 125–346. Vienna: Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei.