ABSTRACT

Wary of the ‘denial of coevalness’ associated with earlier anthropology, anthropologists at the turn of the millennium increasingly emphasized how sharing not just space but also time is constitutive of the ethnographic encounter. However, drawing on online and offline fieldwork conducted in Jordan, I use the tensions between a blood feud and the holy month of Ramadan to illustrate how humans often refuse to inhabit each others’ histories and temporal schemes regardless of the presence of anthropologists. I argue that discomfort with acknowledging such refusals of coevalness has increasingly hobbled anthropological description, especially at a time when new communications technologies are re-shaping human experiences of sharing (and not sharing) space and time. I suggest that anthropologists would benefit from following many of the Jordanian Muslims I encountered in attending to how one does not ‘share time’ with various others – as well as the ways in which one does.

Introduction

Recent decades have seen widespread criticism of the once-venerable anthropological distinction between ‘primitive,’ ‘tribal’ societies with ‘closed’ temporal schemes and anthropologists’ ‘modern,’ ‘open’ societies, which can supposedly embrace many different notions of time (Eickelman Citation1977: 39–40). This critique is perhaps best embodied in Johannes Fabian’s unapologetically polemical classic Time and the Other (Citation1983), which identified a tendency in anthropology towards ‘the denial of coevalness.’ Fabian noted that the same ethnographers who at one moment based their authority on having spent time with a particular group of people would, alternately, cast those same people into a different time in their writing (Citation1983, 31). For Fabian, denying coevalness could be something as subtle as the ‘ethnographic present’, which involved scientific-sounding statements like ‘the x are y’ that rendered peoples and their practices as homogenous and eternal rather than historically contingent – all while erasing the dialogic ethnographic encounter that produced such ostensibly timeless knowledge (Fabian Citation1983, 80–87). Yet denying coevalness was often overt, explicitly casting the other into the past. For Fabian, ‘primitive being essentially a temporal concept, is a category, not an object, of Western thought.’ The same went for ‘tribal, traditional, Third World or whatever euphemism is current’ (Fabian 17–18). Fabian argued that these were all objectifying devices that supported the Western anthropologist’s ‘psychological ingestion and appropriation … of the other,’ a sort of ‘cannibalism’ (Citation1983, 94). In a 2014 ‘retrospective’ on Time and the Other, Fabian explained his work’s far-reaching influence as an outgrowth of ‘field situations that changed radically when our discipline could no longer be exercised in a colonial and imperial state of affairs (when, in fact, it lost its traditional object, the primitive, the native, the tribe, and so forth)’ (Citation2014, 206). Yet while Fabian rightly sensitized anthropologists to the idea that ‘the anthropologist qua ethnographer is not free to ‘grant’ or ‘deny’ coevalness to his interlocutor’ (Citation1983, 32), he has had very little to say about how an interlocutor might refuse coevalness by rejecting the ethnographer’s temporalizations.

If Fabian was reticent to even ‘distinguish’ between denials of coevalness and such refusals of coevalness ‘at the present time’ (Citation1983, 154), it seems worth revisiting this distinction for at least three reasons. First, there is increasing recognition that refusal can be generative – both within the ethnographic encounter (Ortner Citation1995) and the contemporary political field more broadly (McGranahan Citation2016). For instance, in Audra Simpson’s Mohawk Interruptus (Citation2014), refusal becomes a potent political rejoinder to a North American liberal multicultural regime of recognition that places constraints on how government-recognized ‘tribes’ of ‘natives’ can name and critique the coloniality of their predicament. While Fabian might want to cast talk of ‘natives’ and ‘tribes’ and so forth into the past along with colonialism and imperialism, not all ethnographic interlocutors are so eager to accede.

Second, the concept of temporality (along with Fabian’s ‘temporalization’) has developed apace. Scholars engaging a range of marginalized communities have identified what Paul Gilroy termed ‘the distinctive and disjunctive temporality of the subordinated’ (Citation1993, 212), from precarity (Han Citation2018) to ‘crip time’ and ‘queer time’ (Kafer Citation2013, 34 et passim). In a parallel development, where Fabian conceptualized temporalization as a feature of ethnography qua ‘scientific discourse’ (Citation1983, 23), Nancy Munn and other anthropologists have been inspired by Fabian to theorize how temporalization is fundamental to the human condition in general (Munn Citation1992, 99, 104). This has helped popularize ‘a notion of ‘temporalization’ that views time as a symbolic process continually being produced in everyday practices.’ This is a far-reaching ‘sociocultural time with multiple dimensions (sequencing, timing, past-present-future relations etc.)’ that people are ‘in’ but also ‘forming through their projects’ (Munn Citation1992, 116). Growing interest in how everyone temporalizes – including some of the most marginalized – highlights the risks of overestimating ethnography’s institutional power to reify particular temporalities.

Third, recent scholarship also suggests that new communication technologies and their modalities of authorship and publicity may further exaggerate temporal divides. Emphasizing the fragmented, ‘leaking’ subjectivities that emerge through the agonistic back-and-forth of online communication (as opposed to the more bounded forms of subjectivity associated with the modern Arab novel), the literary theorist Tarek El-Ariss claims, ‘this recoding of the text and of the author function is tied to a model of tribal warfare that erupts through a portal into the archaic in cyberspace’ (Citation2019, 29). In their critical engagement with modernism and its cultural products, scholars like El-Ariss pose a question: if we think of newspapers as the moderns’ ‘substitute for morning prayers’ (Anderson [1983] Citation2006, 35–36) that once created grand ‘imagined communities’ with senses of shared history on unprecedented scales, does it follow that new media and the social movements they spawn will continue the trend or will those communities fragment? And what is lost if we rush to assimilate events on social media to a secular Euro-centric calendar without attending to other histories?

Where Fabian’s ideal of ‘coevalness’ in the ethnographic encounter ‘aims at recognizing cotemporality as the condition for truly dialectical confrontation between persons as well as societies’ (Citation1983, 154), I have been inspired by the generativity of partially overlapping temporalities and subjectivities – and especially the deep history of the written word in facilitating these messier, more fleeting encounters. Like David Henig, I try to avoid the pitfall of denying coevalness by emphasizing instead ‘multiple sites where these temporal modalities are negotiated and articulated’ (Citation2020, 95) as part and parcel of intersubjective experiences of everyday life. In doing so, I suggest that intersubjectivity may have always been as much about recognizing (and responding appropriately to) special, privileged senses of time as it is (in Fabian’s memorable phrasing), ‘ultimately, about creating shared Time’ (Citation1983, 31).

In what follows, I draw on over a decade of online and offline research on the impact of social media on Jordan. This includes eight months of intensive fieldwork on the ground in Jordan between 2016 and 2019 involving hundreds of informal face-to-face conversations with dozens of Jordanians from all walks of life about their use of social media as well as over 50 more structured face-to-face interviews with intellectuals, journalists, activists, government-recognized ‘tribal judges’, members of the security apparatus, and other important actors. I begin by situating myself ethnographically in relation to a series of tribal clashes that broke out during Ramadan, emphasizing the conflicting temporalities that emerged and came to pit the tribesmen involved in the conflict against the wider Muslim community (of which they were otherwise part). In the next section, I focus on how the very concept of tribe has come to be marginalized in anthropology in recent decades as an embarrassing remnant of an earlier era of anthropology, emphasizing how this has tended to align anthropologists with certain constructions of Islam (and of the Middle East as a region) at the expense of others. In the penultimate section, I show how online and offline invocations of the Quran inspired by the clash between the temporality of the blood feud and the temporality of Ramadan reveal the appeal of the written word itself as a means of transcending Time in ways that trouble Fabian’s ideal of coevalness in ethnographic writing. I conclude by arguing that attention to the refusal of coevalness as a conscious tactic of many anthropological interlocutors (whether with each other or sympathetic ethnographers) offers a way to reengage with histories that emphasize endurance, if not eternity.

The blood feud

In May of 2017 (1438 AH) my fieldwork in Jordan coincided with the holy month of Ramadan. Intrigued by the increasing role of social media in the lives of those I had been working with for over a decade, I had come to Jordan to study how local power structures might be shifting in response to these new technologies. Instead, I predictably found myself dehydrated and under-caffeinated from trying to fast alongside my Muslim interlocutors.Footnote1 I was also spending more time than I would have liked following a series of ‘tribal clashes’ (ashtabikāt ‘asha’iriyya) in the village of Sarih that had become a national sensation among Jordanian Facebook users. A popular genre of Jordanian news item, such ‘tribal clashes’ were always unfortunate but it was seen as a sure sign of the country’s moral predicament for them to coincide with Ramadan. With many praying to God to ‘guide the minds’ of those in conflict, the verdict online and at iftars where people broke their fasts in the evenings seemed relatively uniform: This was ‘ignorance’ (jāhiliyya) and ‘backwardness’ (takhaluf). As one online commenter proclaimed, ‘we carry the most expensive mobile [phones], wear the most prestigious brands and drive the latest models of cars[.] We’re still called Arabs but unfortunately we’re never going to advance [ – ] the backwardness and ignorance will be with us forever.’

The eruption of tribal conflict in the midst of a month ideally devoted to peaceful reflection and charity (and ensuing temporally-charged recriminations) should serve as a stark reminder of the fragility of collective temporal projects even in the most tight-knit communities. However, I also want to linger here on my own failure to achieve full ‘immersion.’ I want to resist both the conceit of ethnographic mastery as well as the analytic closure that the assertion of shared ‘temporality’ in the ethnographic ‘field’ promotes. This assertion is deeply complicit in forestalling frank discussion of the difficulties of achieving shared attunement under even the best of circumstances. As a resident fellow at the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman, where lunch continued to be announced daily by bell, my experience of the drama was both more immediate and more attenuated than during past visits. I was perfectly positioned for fieldwork with the country’s online news sites in the bustling capital city, but the physical as well as cultural distance between my accommodations and the rural communities where I usually live while conducting research left me feeling alienated from certain previously familiar rhythms. Interviews took me, usually via taxi, from office to office to café – including seedy, smoke-filled establishments with special permission to operate during Ramadan during daylight hours. In other ways, however, my sense of attunement to my rural Jordanian friends and their concerns was actually accentuated thanks to the marvels of social media, especially when it came to spectacular events. Even if my commitment to fasting was suffering, I could use my phone to access hundreds of my Jordanian friends anytime I wanted and seemingly ‘keep up’ with the ‘latest’ gossip from anywhere in the world.

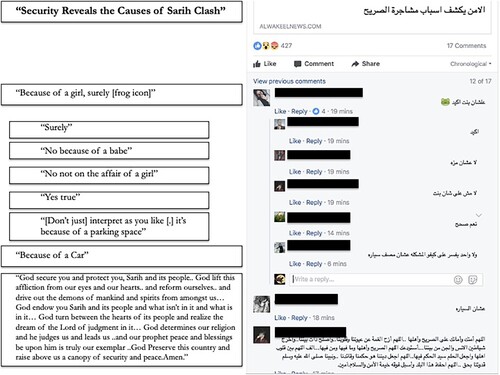

The tribal clashes at the centre of this article purportedly began around the time of afternoon prayers (ṣalāt) a few weeks before Ramadan in the village of Sarih. The initial casus belli (a dispute between two men over a parking space) belies a much more convoluted history of conflict amongst neighbouring families summed up in the journalistic gloss of ‘prior dispute’.Footnote2 Online commentators were quick to suggest everything from ‘a girl’ (see ) to government policies (see ) and even the local football club (see ) might be at issue. The argument escalated when one of the belligerents smashed the window of the others’ car. The commotion soon drew in others from the men’s respective tribes, ending with a member of the ‘Uthmaniyya tribe shooting a pump action shotgun into a crowd of men from the Shiyab tribe, blinding a man in one eye and seriously injuring two others. Then, in a familiar pattern, the dispute ‘moved from the town to the hospital’ as well-wishers and those thirsty for revenge crossed paths. In a fatal moment, a man from the Shiyab tribe was shot and killed.Footnote3 To make matters worse, he was an engineer, a ‘doctor’ in fact: a man with education and prestige who represented his family’s highest aspirations. Supporters of the family claimed that such a crime demanded qisās (retribution): the Quranically-endorsed prerogative of a homicide victim’s kin to have the perpetrator killed.

Anthropologists have long noted how such homicides can profoundly re-structure time and space. With the threat of further revenge attacks or banishment looming, participants swap guarantees of peace for promises of exorbitant payments at some later date in a series of highly ritualized truces (‘atwas) and reconciliations (suliḥs) (cf. Black-Michaud Citation1975; Hasluck in Bohannan Citation1967; Peters Citation1967). These can be negotiated down in subsequent years or become reason for new flare-ups. As Emyrs Peters suggests, the payment of the debt in full would end the relationship. Instead, ‘Debt must be allowed to run between groups, for it is this which creates obligations and perpetuates social relationships’ (Citation1967, 267). Drawing on Peters, Jacob Black-Michaud emphasizes that at least from the perspective of the deceased their kin, feuds are always ‘eternal’ in the sense that nothing can ever really compensate for such a loss. Black-Michaud suggests that homicides can be envisioned as operating like ‘a cursor sliding up and down the scale of genealogical history’ and from which can be derived ‘the type, rules and extent of endemic inter-group hostilities’ (Citation1975, 19). Yet while such deaths help bring groups into being and structure their subsequent movements in space and time, people can also work on group relations through these encounters: a death may be compensated monetarily in return for peace – at least until it becomes socially salient again.

In response to the killing of Dr. Qutiba Al-Shiyab, his kinsmen initially refused to bury the body until they had exacted retribution.Footnote4 While a common feature of such conflicts memorably captured in the opening scenes of Michael Gilsenan’s Lords of the Lebanese Marches, as the anthropologist comes face-to-face with the corpse of the scion of a now-ruined family whose death was never avenged (Citation1996, 29–37), this was at odds with mainstream Sunni practice. According to a number of sayings of the prophet Muhammad recorded in the most authoritative hadith compendia, such funerals should happen as soon as possible. The security apparatus stepped in decisively at this point, pressuring the Shiyab tribe into agreeing to a so-called ‘security truce’ (a contemporary replacement for the traditional ‘truce of the boiling blood’ or fawarat ad-damm of three and one third days). A few days later, leaders of the Shiyab tribe relented and agreed to hold a funeral in return for the killer being charged with murder.

Yet even as the funeral rites were moving forward, the government’s attempts to halt the violence were flagging, with riots breaking out amidst attempts to renew the security truce.Footnote5 In a press release to the media on behalf of the Shiyab tribe, family of the deceased justified their refusal to maintain the peace during Ramadan with reference to a whole range of legitimizing frameworks with their variegated temporalities. They invoked the Quranic injunction to punish murderers, of course, but they also invoked everything from nationalist concerns about the killing of highly skilled ‘cadre’ serving the national cause to humanitarian norms around hospitals as safe-havens from violence. They even invoked the King’s recent efforts to ‘lower the crime rate.’ However, their primary claim was tribal and turned on their prerogative as ‘guardians of the blood’ in keeping with their tribal ‘customs and traditions.’Footnote6 Ramadan or not, the violence continued despite attempts by the security services and senior men to broker lasting truces and organize a reconciliation that would ‘bury’ the conflict for good. It was in this phase that the role of the online audience of fasting Jordanians came to the fore. A cycle of escalating retaliatory violence proceeded to rock the village for weeks in the midst of the holy month of Ramadan. As the conflict progressed, the disturbing press images being disseminated via social media were increasingly drowned out by a nationwide chorus of voices in the comments denouncing the violence and imploring God to restore peace and tranquillity and ‘guide the minds’ of the belligerents (see ).Footnote7 As one journalist I interviewed put it, ‘[Our site] called for the intervention of the big figures and faces and the state to solve the problem … when people saw how this was being reported, they were more ready to solve the problem. This is especially true because this happened during Ramadan and they did not want to go against religion.’

On the one hand there was the time of Ramadan, given in advance by the Islamic calendar and confirmed through physical signs like the moon’s hilāl and the rising and setting of the sun and (in modern times) ratified by government pronouncements and state television. Here one could find the visceral, alternating rhythms of hunger/thirst and satiation and the plodding, patient disposition one must cultivate to master cravings for food, water, caffeine and nicotine from sun-up to sundown. On the other hand, there was the time of the feud, with its own temporality: the three and one third days truce (and longer subsequent truces, whether they were observed or not), the urgency of the decaying corpse, and the demand for quick justice to satiate the moral outrage occasioned by the crime. I want to argue that what my interlocutors and I were experiencing – in ways embodied even at a metabolic level – was a struggle between different projects of what Nancy Munn has termed (inspired by Fabian Citation1983) temporalization. As Munn argues, ‘such strategic temporalizations illuminate ways in which time is not merely ‘lived,’ but ‘constructed’ in the living’ (Citation1992, 109). One could add that time is also very much constructed in death and in notions of the afterlife that demand certain deeply temporal forms of religio-cultural observance (like Ramadan or vengeance).

Where Fabian conceptualized temporalization as a feature of ethnography qua ‘scientific discourse’ and concluded that, ‘in fact, if we remember the history of our discipline, [ethnography] is in the end about the relationship between the West and the Rest’ (Citation1983, 28, my emphasis), Munn was inspired by Fabian to theorize how all human societies temporalize. Munn’s innovation has itself inspired a sprawling research programme studying temporalization – even at the risk of resurrecting all that Fabian critiqued: ‘functionalism, culturalism and structuralism,’ which ‘did not solve the problem of universal human Time’ (Fabian Citation1983, 21). Fabian is surely correct to note that it is ‘characteristic of our discipline’ that, ‘the posited authenticity of a past (savage, tribal, peasant) serves to denounce an inauthentic present,’ but as I hope to show, this is not merely the preserve of Western philosophes travelling in ‘the Orient,’ ‘prefigured by the Christian tradition but crucially transformed in the Age of Enlightenment’ (Citation1983, 10–11). The conflict between the self-styled tribesmen and their pious online detractors certainly reflects engagements with the West (from developmentalist ideologies and social media technologies to Islamic critiques of ‘Western’ technology). Yet it seems reductive to say that ethnography’s institutional force is so ineluctable that everything that comes into its purview must then be about the ‘West and the rest’ – as Fabian says – ‘in the end.’ While significant, ethnography’s powers of objectification should not be overstated – especially in relationship to something as longstanding and far-reaching as Islam. In the next section, I show how a desire to avoid denying coevalness has made it more difficult for anthropologists of Islam (and the Middle East) to recognize the temporal divides that indigenous discourses of ‘tribalism’ index both between those anthropologists and their interlocutors and amongst their interlocutors.

From the denial of coevalness to the refusal of coevalness

With over 13,000 publications citing Time and the Other, a full review of its influence is far beyond the scope of this article. However, it is worth noting some critiques amidst the overwhelmingly positive embrace of Fabian’s ideal of coevalness before focusing on how his ideas have been used in the anthropology of the Middle East to valorize the study of more progressive temporalities at the expense of the self-avowedly primitive or tribal. Frederico Delgado Rosa diagnoses in Fabian a ‘hidden belief in progress’ and especially an extreme eagerness to deny any connection to (much less coevalness with) his own ‘Western’ intellectual ancestors (Citation2019, 27–28). Kevin Birth notes how this sort of ‘coevalness’ can lead to a ‘homochronism’ that reduces the diversity of human histories and temporalities to a simplified narrative of imperial expansion and resistance to that expansion, ironically reifying the very self-other divide that coevalness is supposed to counteract (Citation2008, 14–15). As Seraj Assi notes in The History and Politics of the Bedouin, one of Fabian’s legacies (alongside Talal Asad) has been the wholesale delegitimization of tribes as a legitimate topic of anthropological investigation (Citation2018, 10). Meanwhile, Asad’s anthropology of Islam has emerged as by far the most successful research programme (Schielke Citation2010, 3) responding to these challenges by grounding anthropological investigation in a profoundly diverse textual tradition too big and well-documented to ignore. To be clear, my aim here is not to assess the ultimate merits of Fabian’s intervention – or Asad’s for that matter.Footnote8 Rather, I use the comparatively favourable reception of Asad’s ‘discursive tradition’ paradigm for the anthropology of Islam (vis-à-vis the anthropology of tribalism) to highlight how anthropologists have already begun to productively engage with refusals of coevalness – even if they have yet to be fully conceptualized as such.

Even before the dawn of America’s ‘War on Terror’ in 2001, the ‘Arab’ and ‘Islamic’ ‘world(s)’ had become a repugnant other (Harding Citation1991) par excellance, with Western political commentators often castigating it as medieval, primitive and backward. Drawing on ‘sophisticated critics of anthropology's relationship to colonialism’ (Citation1989, 269) like Fabian, Said and Asad, Lila Abu Lughod found in her classic review of the field that the anthropology of the ‘Arab world’ was orientalist and largely derivative. She identified three main approaches or ‘theoretical metonyms’: ‘Homo Segmentarius’, ‘Harem Studies’ and ‘Islam’ (Citation1989, 280). Singling out tribalism, she urged anthropologists, ‘to stand back … to ask why it has so dominated anthropological discourse on the Middle East’ (Abu Lughod Citation1989, 285). She argued that ‘the current abuses of segmentary theory for the purposes of political analysis are disturbing’ because ‘the Arabs’ alleged failure to modernize, inability to cooperate, despotic rulers, emotionality, mendacity, failure to produce technology or art, and subordination of women are attributed to the legacy of tribalism’ (Abu Lughod Citation1989, 287). Over 20 years later in a follow-up, Jessica Winegar and Lara Deeb noted that ‘tribal social organization has practically vanished as a topic of concern for scholars.’ They describe an ‘urban focus’ that has ‘helped dispel the image of the region as a tribal, exotic, and isolated place’ (Deeb and Winegar Citation2012, 540). Yet as Andrew Shryock (Citation2019:, 30) has argued, all three metonyms (tribalism, gender and Islam) are still consistently used in pop social science and journalism to explain the region (often in precisely the terms anthropologists bemoan), while only tribalism is treated as an inherently suspect anthropological topic.

As Assi argues, there is an agrarian, territorializing, sedentarizing bias uniting modern colonial and anti-colonial movements in which ‘tribal and nomadic elements become no longer imaginable under colonial and national institutions, but are either erased … largely excluded … or modified and integrated’ (Citation2018, 12). The clearest evidence for the persistent odium of ‘backwardness’ accompanying tribalism is how contemporary English-language scholarship (usually political science or international relations) is now at pains to show how it is dynamic, modern, and easily adapted to the needs of the day (Khoury and Kostiner Citation1991; Tapper Citation2009; Watkins Citation2014), often with an emphasis on Western involvement whether in the form of sanctions regimes (Baram Citation1997) or proxy wars (Al-Mohammad Citation2011; Dukhan Citation2019; González Citation2009).Footnote9 A particularly intriguing development, however, is a growing interest in tribal justice as a model of restorative justice that might offer solutions to contemporary problems, whether in the form of monetary compensation for crimes (Ben Hounet Citation2021) or by promoting the value of mercy (Osanloo Citation2020). Arguably, I too ultimately take a similar tack here in emphasizing the relevance of contemporary Jordanian ‘asha’iriyya (tribalism) to understanding social media, with the increasing entextualization and codification of everyday life allowing me to manipulate the phenomenological ‘immediacy’ of ethnographic data in new ways.

One reason why the anthropology of Islam successfully eclipsed the study of ‘Homo Segmentarius’ then is because so many both in ‘the region’ and beyond find its pathologization of tribalism convincing – and take it for granted that anyone indulging in tribalism (or, worse, studying it) is primitive and backward and bears outsized responsibility for the region’s problems. Far from being some recent colonial import, though, the association between tribalism and primitivism has a venerable pedigree: the fourteenth century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun’s anthropology put the Bedouin tribesman at the beginning of a developmental trajectory. For Ibn Khaldun, civilization emerged fitfully from these vital tribal beginnings and hence remained constantly under threat from its forces, both those amassed on the margins of the fertile valleys where Islamic states flourished and latent within the family drama of the dynastic politics at its core.Footnote10 This discourse has been self-consciously preserved by Muslim urbanites, like the scion of a respected Jerusalem family who once quoted me Ibn Khaldun’s aphorism, yajid al-‘arab yajid al-kharab: where the tribes are found, ruins are found ([1377] Citation2015, 118–119).Footnote11 This worldview informs both Islamic activism aimed at discouraging tribalism and jāhiliyya (ignorance) (Shepard Citation2003, 523) and lay and scholarly framings of Islam as a reaction to the excesses of tribalism in the pre-Islamic period so often referred to as the ‘age of ignorance’ (e.g. Aslan Citation2011, 29–32).

In this spirit, rather than assimilating Islam into the post-enlightenment ‘episteme of natural history’ based on the increasing abstraction and universalization of Time as Fabian envisioned (Citation1983, 26), the anthropology of Islam under Asad’s tutelage has come to approach the faith methodologically as a ‘discursive tradition.’ Within this framework, Islam should be approached ‘as Muslims do, from … the founding texts of the Quran and the Hadith’ (Asad Citation[1986] 2009, 20). Here, Islam can be mobilized as a critical foil to Western liberalism and secularism, elaborating many Muslims’ refusals of coevalness with Western temporal projects and thereby challenging those projects’ received wisdom in anthropology. Islamic temporalities can help parochialize what Henig characterizes as the ‘secular forward-moving temporality favoured in the existing scholarship’ (Citation2020, 93). Part of what has made this such a successful research programme is that it captures a powerful Zeitgeist. For instance, as Lara Deeb has shown, even Shi‘i religious movements, traditionally defined precisely by their belief in the importance of a spiritual elect to mediate between texts and the masses, have come to embrace more textualist views of the faith. The result has been a massive push for what she calls the ‘authentication’ of Islamic traditions through a practical efflorescence of lay religious study, especially among women (Deeb Citation2006, 20–23). Sunni reformers have also become concerned with the reproduction of taqlīd, ‘blind repetition’ that masquerades as authentic, originary Islam but actually represents what they term innovations (bidʻāt). With a proliferation of instruction in ‘authentic’ Islam in mosques (Mahmood Citation2005), political movements (Deeb Citation2006) and even mass mediated forms like the cassette tape (Hirschkind Citation2006), the anthropology of Islam has been perfectly positioned to capture the action.

As the anthropology of Islam has shown, associations with the past and assertions of alternative temporality are not inherently pejorative and may even be embraced in moments ripe for ethnographic refusal where people refuse coevalness with each other and even with sympathetic ethnographers. Even the many devout Muslims who reject the Bedouin lifestyle as ‘backward’ may nonetheless seek a return to the vigour of Islam’s golden age and shun ‘innovations’ to ritual practice as morally questionable and polluting. Self-styled Bedouin tribesmen merely go further, equating ‘civilization’ with decadence, which is to say decay, loss of vigour and ultimately death. Of course Asad’s research programme for the anthropology of Islam has not been without its critics: for instance, Samuli Schielke has suggested that the image of Islam advanced by much of the anthropology of Islam is ‘too perfect’ (Citation2009: S36) and even to declare that there is ‘too much Islam’ in the anthropology of Islam (Citation2010, 2). Then there is Amira Mittermaier’s apt retort that there may also be ‘too little Islam’ in the anthropology of Islam – especially attention to ways of being Muslim that are not ‘tied to the rhetoric of Muslim reformism and rationalism’ (Citation2012, 250). Both have sought to study how Muslims live their faith in the ‘everyday’ through ritual practice. In a sensitive portrayal of these dilemmas entitled ‘Being Good During Ramadan’, Schielke makes an important connection between Islam and temporality, noting a common if ‘highly utilitarian’ view of Islam where Ramadan is ‘established as a moral and pious exception from not so perfect everyday life’ (Schielke Citation2009: S28). However, Daniel Birchok (Citation2019) has pushed the exploration of temporality in Islam further through his notion of the ‘Islamic everyday’ in which a whole range of temporalities can coexist within and beyond a wider Islamic discursive tradition. This focus on embodied ritual practice dramatizes the degree to which shared temporality may remain partial even in the most idealized local, face-to-face encounters. In what follows, I try to draw out how an overinvestment in specific relations of coevalness can distort the interplay of divergent temporal orientations in the ethnographic encounter.

Ramadan, the Quran and the making of sacred time

While I hasten to note that a widespread reticence about discussing speculative theology (kalām) represents one of the most intriguing challenges of trying to understand the range of temporalities in contemporary Jordan, I still elicited a diverse range of explicit theological opinions about Time. Even something as seemingly innocuous as a stray comment about prayer beads (misbaḥa, see ) could become an incitement to discourse: used as mnemonics to help count repetitive litanies of Quranic prayers (dhikr), some neighbours once warned me that they too were an innovation (bidʻah) and dangerously close to idolatry (shirk). The eldest explained that, ‘God, praise be unto him, in his wisdom gave us hands like this so that we would have no need for misbaḥa to praise him’ and then proceeded to teach me how to count out sets of 33 prayers (dhikr) on the bones of my fingers, chanting all praise be to God, praise God and God is most Great. The rhythmic engagement with the physical beads was seen as a distracting ‘innovation’ threatening believers’ attempts to reunite with God in the hereafter in eternity. Like fasting, the deeply embodied temporality of such Quranic prayer litanies underlines how recognizing and responding appropriately to subtle everyday refusals of coevalness can be a condition of possibility for deeper ethnographic engagement. I aim to capture how such refusals of coevalness that court what Fabian calls ‘Western rational disbelief’ (Citation1983, 34) stubbornly inhere in ethnographic encounters. I move between online and offline ethnography of the tribal clashes – and between Quranic formulae in everyday life with their tacit, often embodied temporalities (like the cyclical rhythm of the beads) and more explicitly theological terrain where otherwise implicit constructions of temporality and causality can be theorized – even if doing so always risks sowing discord.

Figure 5. Prayer beads (masbiha) and a plaque bearing Surat-an-nas (the final book of the Quran) hang from a car’s rear-view mirror. Electronic counters like the one on the turn signal have increasingly become an alternative to prayer beads, allowing users to better track of their daily prayer totals.

According to the Islamic, hijri, calendar, Ramadan begins every 12 lunar months as indicated by the appearance of the first sliver of the crescent moon or hilāl. This works out to about ten days earlier every solar year, such that the month of Ramadan moves through the solar calendar every 36 years or so (Eickelman Citation1977: 45). Debates about the exact start and end dates of Ramadan are as predictable as the coming of the new moon itself and, as On Barak notes, the practice of relying on the eye-witness testimony of a respected community member that began during the life of the prophet has been superseded by a nationalization of deliberations that often results in different countries observing Ramadan at slightly different times (Citation2013, 124–126). Nonetheless, most Muslims agree that the month should be a time of prayer, reflection, abstinence and charity – a time in which even raising one’s voice (much less violence) is widely seen as a form of rebellion against God. Those able to do so are expected to abstain from any food, drink, smoking, and sex from sunrise until sunset, typically rising before dawn for a meal known as the sahūr that will be their only sustenance until they eat their faṭūr after dusk, often in a festive atmosphere gathered with family, neighbours and friends.

The Quran tells us that it was first revealed during Ramadan and hence Ramadan exemplifies the mystery of how the ‘word’ of God acts in Time. The question fascinated both those who later compiled the sayings of the prophet Muhammad as well as even later theologians. The former recorded a series of distinctive lines of transmission and chains of custody stretching from God (who is emphatically outside of both His creation and Time itself) to the ‘lowest heaven’ (conceptualized as a series of concentric spheres around the earth). There the Quran can be found on a ‘well-preserved tablet’ alongside ‘a complete description of every real and possible determination (qadr) of everything that will be, or could have been, created’ (Mol Citation2017, 76–77), reflecting, but also standing outside of human Time. From here, opinions diverge about how the Quran was conveyed to Muhammad, but the descent of the Quran is strongly associated with laylat al-qadr or the night of power, today linked to the intensification of prayer and retreat into the mosque in the last third of Ramadan and climaxing on the 27th night. Arnold Yasin Mol notes that laylat al-qadr constitutes a ‘sacred time’ that creates a bridge between the seen and unseen realms ‘that is accessible to the whole of creation, as the whole of creation has a temporal aspect’ (Citation2017, 93).

Theologians in contrast attempted to formalize the ontological relationship between the Quran, God, and His creation in Time through debate and polemic rather than ritual. In a notorious episode during the Abbasid dynasty that now serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of excessive polemics, a group known as the Mu’tazilites briefly gained sufficient power to institute an inquisition (miḥna) against those who denied the createdness of the Quran. The Mu’tazilities were rationalists who argued for a notion of a distant God who had created the Quran as form of guidance while allowing humans the freedom to change things for better or worse through their mundane ethical choices. Their chief antagonists were the Ash’arites, a rival group of rationalists who denied the Quran’s historicity completely, arguing that the Quran was uncreated and co-eternal with God: His speech and thus one of His attributes (Mol Citation2017, 75). The Ash’arites went so far in their reading of the Quran as to argue that God re-created the universe from moment to moment in line with His will, with any apparent regularities merely a result of divine habit. Reverberating through one another, Ramadan and the Ash’arite-Mu‘tazalite debate about the ontological status of the Quran in Time invite anthropologists to think more concretely and more abstractly about how humans can (or cannot) individually and communally materialize shared temporalities through writing. As an ethnographer, I find myself humbled by the scope and ambition of what Muslims have temporalized through their engagements with their texts, to say nothing of the various refusals of coevalness that those temporalities may yet incite and, perhaps, necessitate.

So much for the entry of the Quran into Time – but how should humans use the Quran in Time? Like a precocious child, I have often been encouraged in the course of my Arabic language learning for riffing on pious Quranic formulae in my speech in ways my teachers deemed especially contextually appropriate (despite being a foreigner). This can be due either to a literalism yielding comedic effect (like complimenting a cook’s chopping technique with a ‘God protect your hand’) or relative obscurity (ie. specific formulae for funerals or when someone has bathed or cut their hair). As in offline spaces, so in online spaces: there are a panoply of contextually appropriate Quranic sayings that can accompany any specific news report. Many Muslims consider it a virtue to be able to calmly repeat in the face of any adversity ‘no capability or strength except through God’ (la hawla wa la qawa ila bi-allah) and ‘God is sufficient for us and the best disposer of affairs’ (ḥaṣabna allah wani‘m al-wakīl). Other Quranic formulae are more appropriate to bad news, like ‘I take refuge in God from the accursed Satan’ (‘audhu billah min ash-shaytān ar-rajīm) Some formulae, like variations on ‘God guide the mind’ or ‘God guide the soul’ are even more specific to contexts of communal violence while likewise figuring them as unfolding within a larger temporal drama with God at its centre.

Yet Quranic formulae also maintain constructive ambiguity about the nature of Time. The prevaricating use of inshallah (God willing) is somewhat notorious and the more subversively minded also joke that ‘praise God’ (al-ḥamdu lillah) is always an appropriate thing to say: ‘either it’s good or God is testing us,’ goes the jibe. Such formulae might suggest in keeping with Ash’arite theology that God is ultimately responsible for shared Time and what happens in it, but I was also repeated admonished that failing to use such formulae at the right times could thwart even my most admirable desires. I want to highlight the generativity of the partial intersubjectivity of such moments and argue that full coevalness in such situations may be neither ethnographically feasible nor desirable. In fact, the formulae themselves seem to undermine the authority of any mere individual who would presume to explicitly theorize Time on behalf of the whole community, shifting the focus away from anthropology’s most eloquent [and authoritative] ethnographic interlocutors.

Unsurprisingly, the activists, journalists, and intellectuals I interviewed were notably skeptical about taking these Quranic sayings at face value. One prominent lawyer and civil society advocate told me, ‘This is nothing but emotions (‘awāṭif)!’ She explained that the sha‘b [common people] were not given over to theological speculation (kalām) and that comments asking God to ‘guide the minds’ of antagonists ‘have no connection to religion. It is a way of insulting the person or the village or the family’ by implying they were godless, backwards and ignorant. It was not just well-educated urbanites who disparaged the sincerity of such utterances. Even members of the rural working classes, and especially those most committed to the Islamic movement, warned me to beware of the prevalence of ‘flattery’ and outright ‘hypocrisy’ as common social ills associated with such Quranic formulae. One man I knew, a notorious liar, was given the nickname dhakart-allah? ‘have you mentioned God[`s name]?’ by our neighbours in the village because of his tendency to repeat the phrase almost non-stop when he was dissembling. Asking others to pray could be an effective way of taking up discursive space, calling out for those assembled to ‘pray for the prophet’ (ṣalī ‘ala an-nabī) and using the time while those assembled were responding, ‘God bless him and grant him peace’ to begin making one’s case. As a result, there was often a good deal of constructive ambiguity about the degree to which such formulae were intended as simple supplications to God and to what extent they might be an opening to more practical forms of temporalization. On one level, one was obviously supposed to ask God to do something because one wanted God to do it and because the subsequent course of events was contingent on God’s will. I did not even need to ask people to establish this social fact because people were eager to tell me they were teaching me these formulae for precisely these reasons. Yet I was also told that this was all wrong – that I should focus on using these formulae to purify my soul and facilitate my return to God the Eternal.Footnote12

Quranic formulae promised to be efficacious in many ways – including refusing coevalness overtly via polemic and even covertly, by actively producing a constructive ambiguity that allowed people prioritizing different projects of temporalization to coexist and even cooperate. A number of people, including both those working within Jordan’s media sector and members of the sector’s intended audience, noted Quranic formulae could be posted online not to make a statement about theology or temporality but merely as a non-controversial way to follow a particular story and receive notifications of further comments.Footnote13 Given that most of these articles were highly sanitized police reports that studiously avoided naming the families involved (so as not to ‘widen’ the conflict), the most useful information was usually in the comments. Subsequent comments might shed light on the most mundane concerns, like details about the identities of the antagonists or even timely reports on ensuing traffic disruptions. As I already noted, many commenters figured the story firmly within a mundane history of village interpersonal dramas centred around social and biological reproduction early on (). ‘Because of a girl, obviously,’ read one comment. Perhaps not having read the article (or merely following a local belief that such conflicts are ultimately about sex), a number of people seconded this assessment, but then one person disagreed. Another commenter, summarizing the article’s description of the fight over the parking space, wrote ‘because of a car.’ Later on, others seemed to mostly be seeking more information, yet still reproducing a kinship-centred discourse with questions like, ‘Who are the families?’

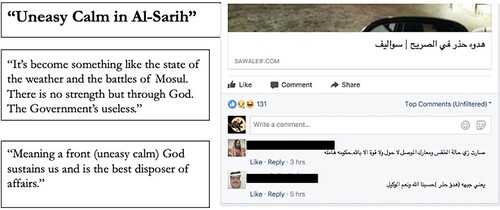

It is only in the following comment that Islamic formulae emerge, rejecting more mundane histories and figuring the conflict within a more soteriologically-informed history by imploring God to help humans reform themselves: ‘God secure you and protect you, Sarih and its people.. God lift this affliction from our eyes and our hearts.. and reform ourselves.. and drive out the demons of mankind and spirits from amongst us..’ However, to the degree that such comments start to sound like a litany of clichés, they might undermine one’s certainty about the sincerity of some of the more apparently overwrought examples. Seeming to combine a number of potential causal frameworks and temporal schemas within a single opaque comment (see ), one person wrote, ‘it’s become something like the state of the weather, the battles of Mosul [Iraq, referring to the neighbouring country’s civil war]. There is no strength but through God. The government is useless.’ Such comments suggest the possibility of partaking in multiple temporalities at once (Birchok Citation2019; Henig Citation2020), for instance combining mundane political histories with soteriological and even eschatological concerns, while still negotiating – even refusing – coevalness in complex ways.

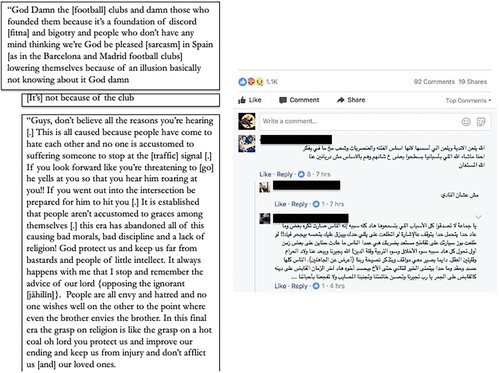

This pushes my analysis of conflicting temporalities back on disagreements where people explicitly argue about alternative histories and causal frameworks to better understand what is actually at stake when Quranic formulae are deployed – even if such polemics are suspect from the perspective of the Sunni tradition. In some instances, a person would blame more mundane causes only to be urged by others to consider more theological matters. For instance, a man blamed local sports clubs, only to be chastised for failing to attend to the more spiritual causes of the strife (see ): ‘Guys, don’t believe all the reasons you’re hearing … People are all envy and hatred and no one wishes well on the other to the point where even the brother envies the brother. In this final era the grasp on religion is like the grasp on a hot coal [.] oh Lord you protect us … .’ Whether comments focus on mundane temporalities of the sports clubs’ schedule or the apocalyptic temporality of ‘the final era’ before the day of judgment, these formulae help to sink a specific causal framework into the minutiae of discursive practice, imbuing petty jealousies with cosmic significance.

The real power of this discursive technique only becomes apparent in aggregate, when the rhythmic repetition of these formulae swamps other discourse (see ), refusing coevalness by drowning out everything else. It was these rows upon rows of repetitive formulae that first drew me into this particular clash and the study of these pious exhortations. In this case in particular, in the face of widespread accusations that they were ‘ruining Ramadan,’ leaders of the respective families were forced to make amends and compel their kinsmen to do the same amidst ostensibly national revulsion at their behaviour. When I asked people in 2019 if social media could ever resolve conflict, this particular feud’s resolution through widespread calls for God to ‘guide the mind’ was the only example people gave. Yet those typing the myriad of pious formulae would often, depending on context, be the first to say that their prayers (du‘ā’s) were not decisive – God’s will was.

Whether or not one believes humans are actually capable of making their own histories, alternative temporalizations seem to proliferate and, in such a context, ethnography is just one temporalizing and historicizing discourse among many, employing many of the same narrative and rhetorical techniques that ethnographic interlocutors employ. Ethnographic interlocutors also often have strong opinions about time – and with whom they wish to share it. For me, taking coevalness seriously eventually led to a realization that I had exceptionalized ethnography as a special kind of temporalizing discourse. Insisting on coevalness had allowed me to devour all other temporalizing discourses in a manner reminiscent of how, Asad reminds us, the Higher Biblical Criticism’s move to wrest previously sacred texts from ‘mythic time’ and subject to them historicism helped carve out a space of epistemic privilege for the modern social sciences in the first place (Citation2003, 37–45).Footnote14 In such a context, the ability to truly share temporality seems highly contingent, something often revealed when people discussed whether and to what degree my fasting as a non-Muslim constituted participation in Ramadan. While always appreciative and unfailingly polite about it, plenty of people pointed out matter-of-factly that I wasn’t really participating in Ramadan since I was not a Muslim and hence would derive no benefit in the hereafter. In other words, as a non-Muslim my attempts to participate were simply insufficient and it was not merely up to me as an anthropologist to determine if my interlocutors and I had achieved true coevalness. In fact, our very ability to communicate helped to underline (in sometimes excruciating detail) precisely all the ways in which we were not, in fact, ‘sharing time.’ Rather than assuming coevalness, ethnographers and their publics should be interrogating what the conditions of possibility for such an assertion might be and what that assertion might be masking about alternative temporalizations. Above all, when people refuse coevalness, anthropologists should listen and ask why.

Conclusion: ethnographic refusal and the refusal of coevalness

A common anthropological conceit today would be to reveal how the ostensible conflicts over time that have been detailed in this article are somehow really about sociality, belonging or, most popular today, ethics and morality. Instead, I have sought to return (via an ethnography of Islam in Jordan) to Munn’s classic observation that these things necessarily happen in time. From periodic fasting to daily prayer times and debates about the nature of agency, intentionality and cause and effect, it is not simply in Islam that morality is about doing the right thing at the right time. However, I have tried to use contemporary Jordan to showcase a range of these competing projects. Most notable here are the highly self-conscious temporalizations of powerful kin groups willing to flaunt religious conventions around Ramadan to honour their ‘customs and traditions’ and pious Muslims more or less prone to explicit reflection on how to engage with an all-powerful deity without adopting ‘innovations’ that threaten to divert believers from authentic, primitive monotheism and their ultimate return to God’s eternal embrace. These temporal projects mobilize complex infrastructures as well as physical and biological processes to shape humans both individually and collectively, including their thought patterns and metabolic processes. Where Ramadan highlights digestion, the feud foregrounds circulation. While these divergences can normally coexist, in other moments different temporalities assert themselves forcefully, even violently. The temporality of the blood feud impinges upon the temporality of Ramadan. Believers in turn deploy a litany of Quranic formulae in online comments figuring the tribesmen as backward and ‘ignorant’, hearkening back to a pre-Islamic ‘Age of Ignorance’ of degraded monotheism.

Yet even in disagreement, there may be concord on the major stakes: rather than making an alternative claim to modernity and the future, Bedouin tribesmen often assert their own alternative project of temporalization in which the past is valorized for its authenticity and honour, while the future can only bring decay. For their part, many traditionalist Muslims agree that the past (especially Islam’s golden age) is morally superior to the present and future, where questionable ‘innovations’ proliferate. For ethnographers to force such interlocutors into a relationship of coevalness against their will seems foolish. Interlocutors may well see the ethnographer’s modernity and cosmopolitanism and want nothing of it – even finding it disgusting. To condescendingly extend that temporality as some sort of gift conferring humanity will do little to promote greater understanding. In fact, it participates in the ongoing erasure of alternative human worlds that might not just challenge the ‘modern’ ‘civilization’ of the ethnographer but actually transform and outlast it in as-yet unimagined ways.

Acknowledgments

This research would have been impossible without the generous assistance of the many anonymous Jordanians from Sarih and elsewhere who shared their thoughts and experiences with me. Financial support for this research was provided by the US National Endowment for the Humanities and the British Academy. Barbara Porter and the American Center of Oriental Research in Amman proved to be excellent hosts during my stay in 2017. I am especially grateful to Stuart Strange, Douglas Farrer, Kawa Murad, Andrew Shryock, James Meador, Matan Kaminer, Blaire Andres, Christine Sargent, the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful comments and encouragement.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Jordanian police only enforce the fast in public spaces (Tobin Citation2016, 51–56) and there are plenty of legitimate reasons why Muslims might not be fasting and no expectation that a non-Muslim like myself should fast, but I try to share the experience of fasting during fieldwork anyway – especially when I have been invited to an ifṭār.

2 https://tinyurl.com/mwn99mr6

3 https://tinyurl.com/ywxzf5rh

4 https://tinyurl.com/2px39znv

5 https://tinyurl.com/53za8dcs

6 https://tinyurl.com/mwpe9nzc

7 https://tinyurl.com/mr46h2pp

8 Asad offers an incisive critique of how earlier anthropological conceptualizations of ‘tribe’ often masked a diverse range of social systems (Asad Citation[1986] 2009, 9–19) and even of the ‘pseudoscientific notion of ‘fieldwork’’ (Citation2003, 17).

9 In contrast, Yazan Doughan (Citation2019, 63) has recently noted a revisionist trend in contemporary Arabic-language historiography seeking a usable past in Jordan’s tribal uprisings of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, suggesting a wider reevaluation of tribalism is afoot. See also Frederick Wojnarowski’s Unsettling Times (Citation2021).

10 Of course, for ibn Khaldun, the movement in time was not only linear but also cyclical, with decline inevitably following rise – though I would also hasten to note that such civilizational discourses never fully went out of fashion. Indeed, the enduring popularity of ibn Khaldun since the nineteenth century ([1377] Citation2015: xxvii-xxxv) itself seems indicative of this and also suggests (contra Fabian Citation2014, 201) that anthropologists cannot necessarily ‘assume’ that ‘when our predecessors spoke of primitives, preliterate peoples without history … that they did this without guile.’

11 Despite stereotypes to the contrary (widespread in the region as well), there are Palestinian as well as Jordanian tribes (Assi Citation2018; Watkins Citation2014, 33–43).

12 Allah’s 99 names also include The First (Al-Awal), The Last (Al-Akhir), The Everlasting (Al-Baqi), and The Ever-Living (Al-Hayy)

13 Ieva Jusionyte (Citation2016) reports a similar phenomenon of using comments to follow developments rather than to communicate in South America as a response to state censorship, misinformation campaigns, and the widespread intimidation of journalists.

14 Shahzad Bashir offers a brief overview of some of the multiple temporalities that characterized history-writing in pre-modern Islam and an incisive critique of the tendency in modern historiography to reduce Islamic history to a ‘single timeline’ (Citation2014, 519) privileging the Arabian peninsula and a declensionist periodization.

Works Cited

- Abu Lughod, Lila. 1989. “Zones of Theory in the Anthropology of the Arab World.” Annual Review of Anthropology 18: 267–306. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.18.100189.001411

- Al-Mohammad, Hayder. 2011. “‘You Have car Insurance, we Have Tribes’: Negotiating Everyday Life in Basra and the re-Emergence of Tribalism.” Anthropology of the Middle East 6 (1): 18–34. doi:10.3167/ame.2011.060103

- Anderson, Benedict. [1983] (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

- Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity. London: Stanford University Press.

- Asad, Talal. (1986) 2009. “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam.” Qui Parle? 17 (2): 1–30. doi:10.5250/quiparle.17.2.1

- Aslan, Reza. 2011. No God But God: The Origins, Evolution and Future of Islam. London: Arrow Books.

- Assi, Seraj. 2018. The History and Politics of the Bedouin: Reimagining Nomadism in Modern Palestine. London: Routledge.

- Barak, On. 2013. On Time: Technology and Temporality in Modern Egypt. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Baram, Amatzia. 1997. “Saddam Hussein’s Tribal Policies in Iraq: 1991–1997.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 29: 1–31. doi:10.1017/S0020743800064138

- Bashir, Shahzad. 2014. “On Islamic Time: Rethinking Chronology in the Historiography of Muslim Societies.” History and Theory 53 (4): 519–544. doi:10.1111/hith.10729

- Ben Hounet, Yazid. 2021. Crime and Compensation in North Africa: A Social Anthropology Essay. London: Palgrave.

- Birchok, Daniel. 2019. “Teungku Sum’s Dilemma: Ethical Time, Reflexivity, and the Islamic Everyday.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 9 (2): 269–283. doi:10.1086/705468

- Birth, Kevin. 2008. “The Creation of Coevalness and the Danger of Homochronism.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00475.x

- Black-Michaud, Jacob. 1975. Cohesive Force. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bohannan, Paul. 1967. Law and Warfare: Studies in the Anthropology of Conflict. Garden City, NY: American Museum of Natural History.

- Deeb, Lara. 2006. An Enchanted Modern: Gender and Public Piety in Shi’i Lebanon. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Deeb, Lara, and Jessica Winegar. 2012. “Anthropologies of Arab-Majority Societies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 537–558. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145947

- Doughan, Yazan. 2019. “The Reckoning of History: Young Activists, Tribal Elders, and the Uses of the Past in Jordan.” POMEPS Studies 36: 60–63.

- Dukhan, Haian. 2019. State and Tribes in Syria: Informal Alliances and Conflict Patterns. London: Routledge.

- Eickelman, Dale. 1977. “Time in a Complex Society: A Moroccan Example.” Ethnology 16 (1): 39–55. doi:10.2307/3773102

- El-Ariss, Tarek. 2019. Leaks, Hacks and Scandals: Arab Culture in the Digital Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and The Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Fabian, Johannes. 2014. “Ethnography and Intersubjectivity: Loose Ends.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (1): 199–209. doi:10.14318/hau4.1.008

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

- Gilsenan, Michael. 1996. Lords of the Lebanese Marches: Violence and Narrative in an Arab Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- González, Roberto. 2009. “On “Tribes” and Bribes: “Iraq tribal Study,” al-Anbar’s Awakening, and Social Science.” Focaal 53: 105–116. doi:10.3167/fcl.2009.530107

- Han, Clara. 2018. “Precarity, Precariousness and Vulnerability.” Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 331–343. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041644

- Harding, Susan. 1991. “Representing Fundamentalism: The Problem of the Repugnant Cultural Other.” Social Research 58 (2): 373–393.

- Henig, David. 2020. Remaking Muslim Lives: Everyday Islam in Postwar Bosnia and Herzegovina. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Hirschkind, Charles. 2006. The Ethical Soundscape: Cassette Sermons and Islamic Counterpublics. London: Princeton University Press.

- ibn Khaldun. [1377] (2015). The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History. Franz Rosenthal, Trans. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Jusionyte, Ieva. 2016. “Crimecraft: Journalists, Police, and News Publics in an Argentine Town.” American Ethnologist 43 (3): 451–464. doi:10.1111/amet.12338

- Kafer, Alison. 2013. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Khoury, Philip., and Joseph Kostiner. 1991. Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mahmood, Saba. 2005. The Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- McGranahan, Carole. 2016. “Theorizing Refusal: An Introduction.” Cultural Anthropology 31 (3): 319–325. doi:10.14506/ca31.3.01

- Mittermaier, A. 2012. “Dreams from Elsewhere: Muslim Subjectivities Beyond the Trope of Self-Cultivation.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18 (2): 247–265. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2012.01742.x

- Mol, Arnold Yasin. 2017. “Laylat al-Qadr as Sacred Time: Sacred Cosmology in Sunnī Kalām and Tafsīr.” In Islamic Studies Today: Essays in Honor of Andrew Rippin, 74–97. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004337121_006

- Munn, Nancy. 1992. “The Cultural Anthropology of Time: A Critical Essay.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 93–123. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.000521

- Ortner, Sherry. 1995. “Resistance and the Problem of Ethnographic Refusal.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 37 (1): 173–193. doi:10.1017/S0010417500019587

- Osanloo, A. 2020. Forgiveness Work: Mercy, Law and Victim’s Rights in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peters, Emyrs. 1967. “Some Structural Aspects of the Feud among the Camel-Herding Bedouin of Cyrenaica.” Journal of the International African Institute 37 (3): 261–282. doi:10.2307/1158150

- Rosa, Frederico. 2019. “Totalitarian Critique: Fabian and the History of Primitive Anthropology.” In Disruptive Voices and the Singularity of Histories, edited by R. Darnell, and F. Gleach, 1–50. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Schielke, Samuli. 2009. “Being Good in Ramadan: Ambivalence, Fragmentation, and the Moral Self in the Lives of Young Egyptians.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15 (1): 24–40. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01540.x

- Schielke, Samuli. 2010. “Second Thoughts About the Anthropology of Islam, or how to Make Sense of Grand Schemes in Everyday Life.” Zentrum Moderner Orient Working Papers 2: 1–16.

- Shepard, William. 2003. “Sayyid Qutb’s Doctrine of “Jāhiliyya”.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 35 (1): 521–545. doi:10.1017/S0020743803000229

- Shryock, Andrew. 2019. “Dialogues of Three: Making Sense of Patterns That Outlast Events.” In The Scandal of Continuity in Middle East Anthropology: Form, Duration, Difference, edited by J. Scheele, and A. Shryock, 27–51. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Simpson, Audra. 2014. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Tapper, Richard. 2009. “Tribe and State in Iran and Afghanistan: An Update.” Études Rurales 184: 33–46. doi:10.4000/etudesrurales.10461

- Tobin, Sarah. 2016. Everyday Piety: Islam and Economy in Jordan. London: Cornell University Press.

- Watkins, Jessica. 2014. “Seeking Justice: Tribal Dispute Resolution and Societal Transformation in Jordan.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 46 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1017/S002074381300127X

- Wojnarowski, F. 2021. Unsettling Times: Land, Political Economy and Protest in the Bedouin Villages of Central Jordan (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge).