Abstract

Objective: To assess the effect of asthma exacerbations and mepolizumab treatment on health status of patients with severe asthma using the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ).

Methods: Post hoc analyses were conducted using data from two randomized controlled trials in patients ≥12 years old with severe eosinophilic asthma randomized to receive placebo or mepolizumab 75 mg intravenously (32-week MENSA study) or 100 mg subcutaneously (MENSA/24-week MUSCA studies), and an observational single-visit study in patients with severe asthma (IDEAL). Linear regression models assessed the impact of historical exacerbations on baseline SGRQ total and domain scores (using data from each of the three studies), and within-study severe exacerbations and mepolizumab treatment on end-of-study SGRQ scores (using data from MENSA/MUSCA).

Results: Overall, 1755 patients were included (MENSA, N = 540; MUSCA, N = 551; IDEAL, N = 664). In all studies, higher numbers of historical exacerbations were associated with worse baseline SGRQ total scores. Each additional historical exacerbation (beyond the second [MENSA/MUSCA]) or first [IDEAL] was associated with worsening mean total SGRQ scores of +1.5, +1.1 at baseline and +2.3 within the year prior to study enrollment. During MENSA and MUSCA, each within-study severe exacerbation was associated with a worsening in total SGRQ score of +2.4 and +3.4 points at study end. Independent of exacerbation reduction, mepolizumab accounted for an improvement in total SGRQ score of −5.3 points (MENSA) and −6.2 points (MUSCA).

Conclusions: These findings support an association between a higher number of exacerbations and worse health status in patients with severe (eosinophilic) asthma.

Introduction

Asthma is a complex and heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation and symptoms of wheezing, chest tightness, shortness of breath, and cough that may periodically flare-up during exacerbations (Citation1). Exacerbations can vary in severity from mild to severe, and can occur across the spectrum of asthma severity, but constitute a considerable part of the disease burden in patients with severe asthma (Citation2,Citation3).

Several studies have used validated questionnaires to demonstrate that exacerbations significantly impact on patients’ overall health-related quality of life (Citation3–7). One of the most widely used questionnaires for assessing the perceived health status of respiratory patients is the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (Citation8). The SGRQ is strongly associated with measuring health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); however, the initial development of the SGRQ was in patients with asthma (Citation9) and recent studies have validated its relevance in patients with severe asthma (Citation10,Citation11).

Two cohort studies have assessed the impact of asthma exacerbations on SGRQ scores, with both reporting poorer health status in patients with frequent asthma exacerbations (Citation3,Citation4). Kupczyk et al. reported worse SGRQ total scores in patients experiencing frequent exacerbations, compared with patients experiencing less frequent exacerbations (Citation3). Similarly, Filipowski et al. showed an association between hospitalization due to exacerbations and reduced HRQoL when assessing SGRQ (Citation4). However, neither of these studies quantified the impact of each exacerbation experienced by the patients on worsening of SGRQ scores.

Recently, three studies have reported SGRQ scores and exacerbations in patients with severe asthma and severe eosinophilic asthma (Citation12–14). Two of these were randomized controlled trials (MENSA and MUSCA) which investigated the efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and a history of ≥2 exacerbations (Citation13,Citation14). Mepolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody indicated for patients with severe refractory eosinophilic asthma (Citation15,Citation16). It selectively targets interleukin-5 (IL-5), blocking the binding of IL-5 to its receptor on the surface of eosinophils and ultimately reducing eosinophil levels in blood and sputum (Citation17,Citation18). Furthermore, studies have suggested mepolizumab leads to a reduction in exacerbations rates and improves HRQoL compared with placebo (Citation13,Citation14); however, it is not known if mepolizumab has a direct impact on health status independent of its effect on exacerbation reduction. The third study identified was a cross-sectional, observational cohort study (IDEAL) which aimed to describe the frequency and characteristics of patients with severe asthma phenotypes who would be eligible for treatment with biologics. These three studies (MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL) were chosen for inclusion in this post hoc analysis as they provided SGRQ scores and exacerbation data in a severe asthma population, without the influence of another modifier (eg, oral corticosteroid [OCS] changes). Additionally, patient-level data were available for the analysis.

Here, we present the results of the post hoc analyses of MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL in which we assessed the impact of exacerbations on overall health status (using SGRQ) for each study, as well as the effect of mepolizumab treatment, independent of exacerbation reduction, on patients’ overall perceived health status as measured by the SGRQ scores using data from MENSA and MUSCA. Together, the data from these three studies offer the opportunity to examine the association between exacerbations and patients’ health status using different study designs encompassing both clinical trial and real-world data.

Materials and methods

Study design

The designs of the MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL studies have been reported previously (Citation10,Citation13,Citation14). In brief, MENSA (MEA115588, NCT01691521) was a 32-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effect of mepolizumab treatment on the frequency of exacerbations in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma (Citation13). During MENSA, patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive mepolizumab 100 mg subcutaneous (SC) plus placebo intravenous (IV), or the bioequivalent dose of mepolizumab 75 mg IV plus placebo SC, or placebo SC and IV, every 4 weeks for 32 weeks (final dose at Week 28), in addition to standard of care. This post hoc analysis used combined data from the two doses of mepolizumab.

MUSCA (200862, NCT02281318) was a 24-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy of mepolizumab on health status, as measured by SGRQ total score, in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma (Citation14). In MUSCA, patients were randomly allocated (1:1) to receive mepolizumab 100 mg SC or placebo SC, every 4 weeks for 24 weeks (final dose at Week 20), in addition to standard of care.

The IDEAL study (201722, NCT02293265) was a cross-sectional, single-visit, observational study that described patients with severe asthma across six countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the UK and US) (Citation12). Patients in IDEAL had been receiving standard of care treatment for severe asthma at the physician’s discretion, including high dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) plus at least one of the following: long-acting β2-agonist, leukotriene modifier, theophylline, or continuous or near continuous systemic corticosteroid (SCS).

The effect of mepolizumab on SGRQ score was assessed with post hoc analyses of data from the MENSA and MUSCA studies. The association between frequency of exacerbations and SGRQ score was investigated using analyses of data from the IDEAL study, as well as MENSA and MUSCA, in order to examine if the findings from the randomized controlled trials are consistent with real-world clinical practice and in patients with phenotypically-undefined severe asthma compared with eosinophilic severe asthma.

Patient populations

Eligibility criteria for MENSA and MUSCA have been detailed in the primary publications (Citation13,Citation14). Briefly, patients were ≥12 years old with a diagnosis of severe asthma (according to the European Respiratory Society [ERS]/American Thoracic Society [ATS] guidelines that were applicable during the study enrollment period) (Citation19), and a peripheral blood eosinophil count of ≥150 cells/µL at time of screening or ≥300 cells/µL during the previous year, and a history of ≥2 exacerbations requiring SCSs in the 12 months prior to enrollment. Patients had also been receiving high-dose ICS, with or without maintenance OCS, for ≥12 months prior to enrollment, plus an additional controller therapy for ≥3 consecutive months within the last 12 months.

In the IDEAL study, eligible patients were ≥12 years old, had a diagnosis of severe asthma (ERS/ATS guidelines) (Citation19), and had received high-dose ICS plus an additional controller medication(s) for ≥12 months prior to the study visit. In IDEAL, there were no restrictions on the number of historical exacerbations.

Exacerbations and SGRQ

Within-study severe exacerbations (recorded in MENSA and MUSCA) were defined as a worsening of asthma symptoms requiring a short-course of SCSs and/or an asthma-related hospitalization and/or emergency room (ER) visit. Historic exacerbations were defined as follows: In MENSA and MUSCA, history of SCS-treated exacerbations (defined as requiring treatment with SCS in the 12 months prior to enrollment) was collected at baseline. In IDEAL, history of severe exacerbations (defined as requiring treatment with SCS and/or ER visit and/or hospitalization in the 12 months prior to enrollment) was collected from medical records during the single study visit. The SGRQ was completed at baseline and at the end of study in MENSA; at baseline, three times during the study, and at the end of study in MUSCA; and during the single study visit in IDEAL. The SGRQ total and domain (Symptoms, Activity and Impacts) scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating worse health status. A 4-point difference in SGRQ score has previously been defined as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) (Citation20).

Post hoc analysis

Patients included in this post hoc analysis were from MENSA and MUSCA who had been randomized and received ≥1 dose of study treatment (modified intent-to-treat [mITT] population and the intent-to-treat [ITT] population, respectively) and patients from IDEAL who had completed all the study questionnaires (IDEAL total cohort). Data from all three studies were individually analyzed to investigate the association between history of exacerbations (categorized as ≤2 or >2 SCS-treated exacerbations in the past 12 months for MENSA and MUSCA, and 0, 1 or ≥2 severe exacerbations in the past 12 months for IDEAL) and baseline SGRQ score.

A linear regression model was used to determine the association between historical exacerbations and the baseline SGRQ score (total and domains) in MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL. For MENSA and MUSCA, covariates included the baseline SGRQ score and exacerbations in the prior year as a continuous variable. Covariates included for the IDEAL study data were the baseline SGRQ score, the presence/absence of historical severe exacerbations, and the number of additional severe exacerbations beyond the first one recorded in the prior year.

Data from MENSA and MUSCA were analyzed to assess the impact of within-study severe exacerbations and mepolizumab treatment on patients’ health status. First, changes in SGRQ score from baseline to the end of study were summarized by the number of severe exacerbations (categorized as 0, 1 or ≥2) experienced during the treatment period for mepolizumab versus placebo. Second, the change from baseline to end of study SGRQ scores (total and domain) were calculated using pooled data from all patients with available data in MENSA (mepolizumab 75 mg IV dose and 100 mg SC dose) and all patients in MUSCA. A linear regression model, using the covariates baseline SGRQ score, treatment, and number of severe exacerbations over the study treatment period, was used to evaluate the impact of within-study severe exacerbations on change in SGRQ score between baseline and the end of study following treatment with mepolizumab or placebo for MENSA and MUSCA. Under this parametrization, the treatment effect estimated from the model excluded the improvement in SGRQ score associated with a reduction in exacerbations since these were captured separately within the model. This meant that the treatment effect (final SGRQ scores) could be interpreted as the effect of mepolizumab treatment minus the expected improvement in SGRQ scores due to treatment-related reductions in exacerbations.

Results

Patient populations

In MENSA, 576 patients with severe eosinophilic asthma were included in the mITT population, 540 of whom had available SGRQ data and were included in this analysis. In MUSCA, 551 patients with severe eosinophilic asthma were included in the ITT population, all of whom were subsequently included in this analysis. The demographic data and baseline disease characteristics of the MENSA mITT and the MUSCA ITT populations are stratified by number of SCS-treated exacerbations in the previous year in and by within-study severe exacerbations in . A total of 748 patients were enrolled in observational IDEAL study, resulting in a total cohort of 670 evaluable patients with severe asthma. Of these, 664 had complete SGRQ data and were included in this analysis. Demographics and disease characteristics of the IDEAL cohort stratified by severe exacerbation history are shown in . A summary of baseline SGRQ scores and exacerbation history for patients in MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL, and within-study severe exacerbations for patients in MENSA and MUSCA is provided in .

Table 1. Patient demographics and disease characteristics by SCS-treated exacerbationsTable Footnotea in the MENSA mITT, and MUSCA ITT populations and by severe exacerbationsTable Footnoteb in the previous 12 months for the IDEAL total cohort.

Table 2. Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics by within-study severe exacerbations for MENSA and MUSCA post hoc analysis populations.

Table 3. Summary of baseline SGRQ scores, severe-exacerbation history and within-study severe exacerbations for MENSA mITT and MUSCA ITT populations and IDEAL total cohort.

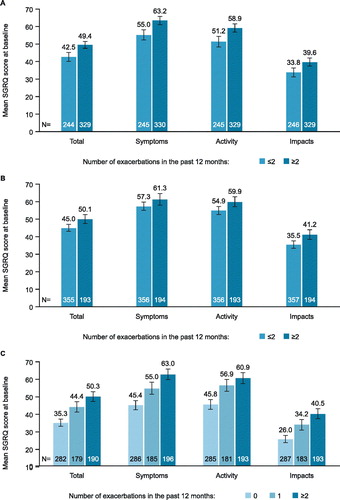

Impact of historical exacerbations on baseline SGRQ

A higher number of historical exacerbations was associated with worse baseline SGRQ total and domain scores compared with lower numbers of historical severe exacerbations in each of the three studies (. The difference in SGRQ total score between the SCS-treated exacerbation subgroups in MENSA and MUSCA (≤2 and >2) and all severe exacerbation subgroups in IDEAL (0, 1 and ≥2) exceeded the MCID of 4 points (Citation20). Due to study entry requirements, all patients enrolled in MENSA and MUSCA had experienced at least 2 SCS-treated exacerbations in the 12 months prior to randomization (with the exception of one patient in MENSA [placebo group] and two patients in MUSCA [one in the placebo group and one in the mepolizumab group]). In MENSA and MUSCA there was a mean worsening in SGRQ total score at baseline of +1.5 and +1.1, respectively, for each additional historical exacerbation beyond the second. This pattern was also found for patients enrolled in MENSA and MUSCA for each of the SGRQ domain scores (). In the IDEAL study, patients who reported no severe exacerbations in the 12 months prior to enrollment showed significantly better (lower) SGRQ total scores compared with patients experiencing ≥1 severe exacerbation (difference: -9.7 points). In addition, there was a further worsening in SGRQ total score of +2.3 points per each additional severe exacerbation within the year prior to study enrollment. A similar pattern was also observed for the SGRQ domain scores ().

Figure 1. Baseline SGRQ total and domain scores by the number of SCS-treated exacerbations† experienced in (A) MENSA or (B) MUSCA and severe exacerbations* experienced in (C) IDEAL studies in the previous 12 months. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *Severe exacerbations were defined as worsening of asthma symptoms requiring a short-course of OCS and/or an asthma-related hospitalization and/or ER visit; †SCS-treated exacerbations were defined as worsening of asthma symptoms, despite ICS use, that require treatment with SCS. ER, emergency room; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Table 4. Regression analysis of baseline SGRQ score by exacerbation history for the MENSA, MUSCA and IDEAL studies.

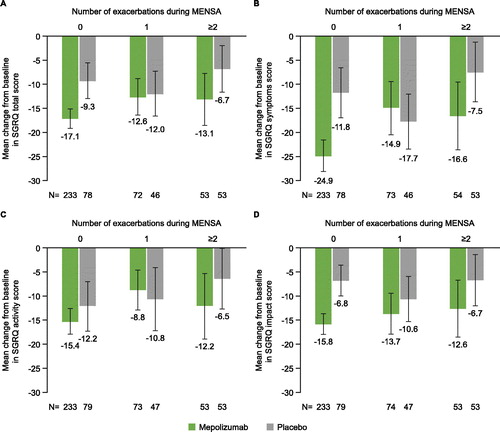

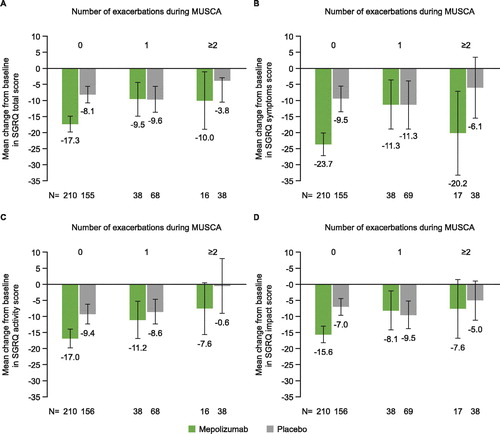

Impact of within-study severe exacerbations and mepolizumab treatment on change from baseline SGRQ scores in MENSA and MUSCA

The primary analyses of MENSA and MUSCA showed a mean improvement (lowering) in SGRQ scores in both mepolizumab and placebo groups between baseline and end of study. This improvement in health status was both clinically and significantly greater in patients treated with mepolizumab than placebo in both studies (Citation13,Citation14). In this post hoc analysis, patients with no within-study severe exacerbations experienced more improvement in SGRQ total and domain scores from baseline to end of study compared with patients with 1 or ≥2 within-study severe exacerbations. Patients in both MENSA and MUSCA who experienced only a single within-study exacerbation reported varying results versus placebo across the total and domain scores ( and ). Overall, the SGRQ total score worsened by +2.4 and +3.4 points for each severe exacerbation experienced during the MENSA and MUSCA treatment periods, respectively (). All SGRQ domain scores worsened with successive severe exacerbations, with the effect being most evident for SGRQ Symptom scores ().

Figure 2. Change from baseline at Week 32 in (A) SGRQ total score, (B) SGRQ symptoms score, (C) SGRQ activity score and (D) SGRQ impact score, by within-study severe exacerbations* experienced during MENSA. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *Severe exacerbations were defined as worsening of asthma symptoms requiring a short-course of OCS and/or an asthma-related hospitalization and/or ER visit. ER, emergency room; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Figure 3. Change from baseline at Week 24 in (A) SGRQ total score, (B) SGRQ Symptoms score, (C) SGRQ Activity score and (D) SGRQ Impact score, by within-study severe exacerbations* experienced during MUSCA. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *Severe exacerbations were defined as worsening of asthma symptoms requiring a short-course of OCS and/or an asthma-related hospitalization and/or ER visit. ER, emergency room; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Table 5. Regression analysis of change from baseline in SGRQ score by within-study severe exacerbations and mepolizumab treatment during the MENSA and MUSCA studies.

In these post hoc analyses, using the linear regression model, it was predicted that mepolizumab accounted for an improvement in SGRQ total score of −5.3 points in MENSA and −6.2 points in MUSCA (). Likewise, the direct effect of mepolizumab on SGRQ Symptoms, Activity and Impacts domain scores followed the same pattern ().

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the association between exacerbations and the perceived health status of patients with severe asthma, as well as the direct impact of mepolizumab treatment, regardless of reductions in exacerbations. The results showed that the numbers of exacerbations, both historical and experienced within the study, and the treatment used, all modify patients’ SGRQ scores. The improvements seen in patients’ SGRQ scores beyond those that can be achieved as a result of reductions in exacerbations may be due to improvements in asthma control, lung function and a reduction in overall systemic inflammation, all of which would have a positive impact on overall wellbeing. These findings highlight the importance of appropriate asthma treatment to control exacerbations and improve patient health status.

These post hoc analyses showed that patients with higher numbers of exacerbations in the previous year had significantly worse baseline SGRQ total and domain scores than patients with fewer historical exacerbations, although the differences were less than the MCID established for SGRQ for all three studies (Citation20). Using regression analysis, it was determined that each additional historical exacerbation (beyond the first [IDEAL] or second [MENSA/MUSCA] exacerbation) experienced in the 12 months prior to enrollment was associated with a similar worsening (greater difference) of 1.1–2.3 units in baseline SGRQ total score. In addition, patients who experienced ≥2 within-study severe exacerbations (MENSA and MUSCA) had substantially worse SGRQ total scores at the end of the study than patients who had none, independent of treatment allocation. Each within-study severe exacerbation was associated with a 2.4–3.4-unit worsening in score. These results demonstrate how exacerbations can potentially impact the perception of patients’ health status.

Examination of the effects of exacerbations on the SGRQ domain scores showed that the trend of worsening SGRQ score with increasing historical exacerbations for the total score was also reflected in all domains. In contrast, within-study exacerbations had larger effects on each domain compared with the historical exacerbations, with the largest effect on the Symptoms domain compared with the other domains (each exacerbation led to a worsening in the Symptoms domain of 4.0–4.8 units). This may be explained by how the different domains are measured. The Symptoms domain covers the patient’s recollection of symptoms over a preceding recall period and offers insight into perceived disease state, whereas the Activity and Impacts domains address a patient’s experience of current disease experience (Citation21). It is known from COPD that full recovery from an exacerbation is prolonged (Citation22). This is likely to be similar in severe asthma (although perhaps not as prolonged), but has not been studied. The Symptoms domain is retrospective, which could reflect the patients’ recollection of an event that took place during the recall period, but outside the time interval in which recovery of an exacerbation may have occurred. Thus, Symptoms domain scores may show a greater effect of an exacerbation than the Activity and Impact scores. Unfortunately, the time at which any event happened during the trial was not available, so this hypothesis cannot be tested. Comparisons of historical exacerbations and within-study exacerbations on SGRQ score are difficult to evaluate as data on historical exacerbations were derived from clinical practice, while within-study exacerbation data were obtained from clinical trials only.

MENSA and MUSCA were both randomized controlled trials, where patients were either treated with placebo or mepolizumab. These trials showed that mepolizumab is capable of decreasing exacerbations as well as improving health status (Citation13,Citation14). It is often challenging to clarify the association between exacerbations and health status measurements (Citation6) and to determine if treatments offer an added benefit for improving perceived health status beyond their ability to reduce exacerbations. In this analysis, using linear regression, the predicted change in SGRQ score attributable to mepolizumab beyond exacerbation reduction was estimated and found to be associated with clinically relevant improvements in SGRQ (mean decreases of 5.3–6.2 points). These results show that mepolizumab has a direct beneficial effect on patients’ health status, which operates via a different mechanism to that which results in exacerbation reduction; this may be related to the reduction of systemic inflammation, and improvements in daily lung function and symptoms and asthma control. Furthermore, the impact on health status was observed at the end of study treatment, separated in time from the occurrence of the exacerbation, supporting the sustained benefit of treatment with mepolizumab.

This analysis included different types of studies and aimed to determine whether there is a consistent association between exacerbations and health status across both clinical trial and real-world settings. MENSA and MUSCA were both randomized controlled trials enrolling only patients with severe eosinophilic asthma; in contrast, IDEAL was a cross-sectional study enrolling patients with severe asthma that was phenotypically undefined. Despite the differences in patient population and study design, the findings of the clinical trials with more stringent entry criteria are supported by the analysis of the observational study, suggesting the association between exacerbations and patient-perceived health status is applicable in real-life clinical practice, thus providing a more robust result.

The principal limitation of these post hoc analyses is that the presence of exacerbations is an element in the definition of asthma severity, as well as an outcome, which makes it difficult to determine exacerbation-independent causality of changes in health status. For instance, the definition of severe asthma according to Global Initiative for Asthma depends on the ability of asthma medication to maintain control and prevent exacerbations (Citation1). The SGRQ score is also derived in part by elements of exacerbations as it contains questions about past “attacks” of wheezing and chest trouble, although this is confined to the Symptoms domain that is the smallest part of the questionnaire (Citation21). It should be noted that the Activity and Impacts domains, which contain no indirect references to exacerbations, show a non-exacerbation related benefit of treatment. However, the treatment benefit on health status, independent of exacerbation prevention, could only be determined if there was an adequate number of patients who had no exacerbations during the study period (in all treatment arms). In this study, this problem was mitigated by using an analysis of covariance with adjustments for baseline SGRQ and exacerbations during the study to estimate the exacerbation-independent effect of mepolizumab in patients with severe asthma.

Conclusion

Findings from these post hoc analyses demonstrate an association between more frequent asthma exacerbations and a worsening of patients’ perceived health status. Although exacerbations are considered to be acute episodes, the results presented indicate that frequent exacerbations in patients with severe asthma lead to long-term impacts on health status. Furthermore, they indicate that treatment with mepolizumab may improve health status by mechanisms that are separate from those that result in exacerbation prevention. This supports the use of mepolizumab to treat patients with severe eosinophilic asthma to sustain health status and improve patients’ perception of their health status.

Declaration of interest

LMN, SMC, NBG, PJ, FCA and ESB are employees of GSK and hold stocks/shares in GSK. HM was an employee of GSK at the time of the study and owns stocks/shares in GSK; HM is now employed by AstraZeneca.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript and the analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in critically revising the work for important intellectual content, approved of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft based on author input, assembling tables and figures, collating authors comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Mary E. Morgan PhD and Natasha Dean MSc at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Data sharing statement

Anonymized individual participant data and study documents for the original studies (IDEAL, MENSA and MUSCA) can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. Available from: http://ginasthmaorg/gina-reports/. 2017.

- Bel EH, Sousa A, Fleming L, Bush A, Chung KF, Versnel J, Wagener AH. Diagnosis and definition of severe refractory asthma: an international consensus statement from the Innovative Medicine Initiative (IMI). Thorax 2011;66:910–917. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.153643.

- Kupczyk M, ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Bel EH, Papi A, Chanez P, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, et al. Frequent exacerbators–a distinct phenotype of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2014;44:212–221. doi: 10.1111/cea.12179.

- Filipowski M, Bozek A, Kozlowska R, Czyżewski D, Jarzab J. The influence of hospitalizations due to exacerbations or spontaneous pneumothoraxes on the quality of life, mental function and symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD or asthma. J Asthma 2014;51:294–298. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.862543.

- Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, Gupta S, Monteiro W, Sousa A, Marshall RP, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. New Eng J Med 2009;360:973–984. Epub 2009/03/07. PubMed PMID: 19264686; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3992367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808991.

- Lloyd A, Price D, Brown R. The impact of asthma exacerbations on health-related quality of life in moderate to severe asthma patients in the UK. Prim Care Respir J: J General Pract Airways Group 2007;16:22–27. Epub 2007/02/14. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00002.

- Luskin AT, Chipps BE, Rasouliyan L, Miller DP, Haselkorn T, Dorenbaum A. Impact of asthma exacerbations and asthma triggers on asthma-related quality of life in patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:544–552. e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.02.011.

- Ferrer M, Villasante C, Alonso J, Sobradillo V, Gabriel R, Vilagut G, Masa JF, Viejo JL, Jiménez-Ruiz CA, Miravitlles M. Interpretation of quality of life scores from the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Eur Respir J 2002;19:405–413.

- Quirk FH, Jones PW. Patients' perception of distress due to symptoms and effects of asthma on daily living and an investigation of possible influential factors. Clin Sci (Lond) 1990;79:17–21.

- Nelsen LM, Kimel M, Murray LT, Ortega H, Cockle SM, Yancey SW, Brusselle G, Albers FC, Jones PW. Qualitative evaluation of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe asthma. Respir Med 2017;126:32–38. Epub 2017/04/22. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.02.021.

- Nelsen LM, Vernon M, Ortega H, Cockle SM, Yancey SW, Brusselle G, Albers FC, Jones PW. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire in patients with severe asthma. Respir Med 2017;128:42–49. Epub 2017/06/15. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.04.015.

- Albers FC, Mullerova H, Gunsoy NB, Shin JY, Nelsen LM, Bradford ES, Cockle SM, Suruki RY. Biologic treatment eligibility for real-world patients with severe asthma: The IDEAL study. J Asthma 2017;55:1–9. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2017.1322611.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, Humbert M, Katz LE, Keene ON, Yancey SW, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. New Engl J Med 2014;371:1198–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403290.

- Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, Bratton DJ, Wang-Jairaj J, Nelsen LM, Trevor JL, Magnan A, ten Brinke A. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:390–400. Epub 2017/04/12. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(17)30125-x.

- FDA. Nucala (mepolizumab) Prescribing Information 2015 [December 2018]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125526s004lbl.pdf.

- EMA. Nucala (mepolizumab) Summary of Product Characteristics 2015 [December 2018]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2015/20151202133270/anx_133270_en.pdf.

- Pelaia C, Vatrella A, Busceti MT, Gallelli L, Terracciano R, Savino R, Pelaia G. Severe eosinophilic asthma: from the pathogenic role of interleukin-5 to the therapeutic action of mepolizumab. Drug Des, Dev Ther 2017;Volume 11:3137–3144. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S150656.

- Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, Bleecker ER, Buhl R, Keene ON, Ortega H, Chanez P. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2012;380:651–659. Epub 2012/08/21. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60988-x.

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343–373. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013.

- Jones PW. Interpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPD. Eur Respir J 2002;19:398–404. Epub 2002/04/09.

- Jones PW, ST George’s Respiratory Questionnaire Manual. St George's Univeristy of London, 2009. Available from: http://www.healthstatus.sgul.ac.uk/SGRQ_download/SGRQ%20Manual%20June%202009.pdf [last Accessed June 2019].

- Spencer S, Jones PW, Group GS. Time course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Thorax 2003;58:589–593. PubMed PMID: 12832673; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1746751. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.7.589.