ABSTRACT

Objective

The 2019 GINA guidance incorporates the presence of T2 inflammation in severe asthma patients to determine eligibility for add-on biologic therapy, though little data exists to characterize this population. The objective of this manuscript is to conduct a descriptive analysis to characterize patients with severe asthma in emerging countries based on disease severity, patient exacerbation history, and T2 phenotype.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of physicians treating asthma patients ages 12 years and older was conducted in eight countries. Physicians characterized their severe asthma patients and reported data from their patients’ medical charts. Medical chart data was selected from the physicians’ six most recent asthma patients taking prescription medication.

Results

A total of 550 physicians completed the survey and filled out 3,300 patient record forms. A total of 876 patients have been characterized with uncontrolled severe asthma. Of the 420 patients with available EOS lab data, 40% are indicated with T2 inflammation (EOS ≥150/µL). Ninety-one percent of all patients with available IgE lab data (n = 498) had IgE 30 − 1500 IU/mL indicating allergy-driven asthma. Finally, chronic OCS use (as reported by physicians) was reported in 11% of patients.

Conclusion

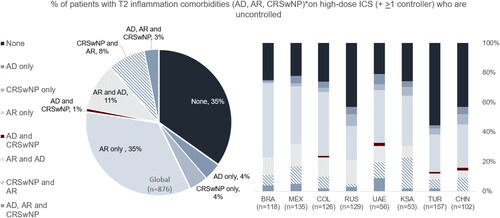

This research revealed that 65% of patients had at least one of three T2 inflammation comorbidities assessed: allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, and atopic dermatitis. Discrepancies were observed between patients’ treatment regimens and GINA step reported, suggesting there may be room to improve understanding of asthma severity as defined per GINA guidelines as well as asthma control assessment in clinical practice.

Introduction

Asthma is a heterogeneous, chronic inflammatory disease characterized by airway inflammation and a history of respiratory symptoms including wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and/or coughing that vary over time, with potential lung function impairment (Citation1). The cause of asthma is not fully understood; it is driven by a complex mix of genetic and environmental factors (Citation1).

According to the 2019 GINA guidelines, asthma severity is evaluated retrospectively from the level of treatment required to control symptoms and can be assessed after patients have been on controller medication for several months.

Severe asthma is recognized as a specific asthma phenotype rather than an extreme manifestation of more common asthma variants (Citation2). GINA guidelines include definitions for uncontrolled, difficult-to-treat, and severe asthma that are all interconnected. Uncontrolled asthma is characterized by poor symptom control and/or frequent or severe exacerbations. Difficult-to-treat asthma is uncontrolled despite the use of medium or high dose ICS with a second controller, or maintenance OCS, or requires these treatments to maintain control and reduce exacerbation risk. Severe asthma is a subset of difficult-to-treat asthma that is uncontrolled despite adherence with maximal optimized therapy and contributory factors (such as incorrect inhaler technic or comorbidities) have been addressed. Patients whose condition worsened when maximal treatment is decreased are also characterized as having severe asthma.

T2 inflammation as a driver of asthma

Research has illuminated the role of type 2 (T2) inflammation in the etiology and pathogenesis of asthma, which opens up the potential for its use to classify asthma severity (Citation3,Citation4). According to studies in patients with non-specified types of asthma (Citation5), mild to moderate asthma (Citation6), uncontrolled asthma (Citation7), and severe asthma (Citation8,Citation9), around 50–70% of asthma patients have type 2 inflammation (Citation8,Citation9).

T2 inflammation is driven by both the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune system. Cells in the adaptive arm (Th0 and Th2 cells) and the innate arm (ILC2 cells, mast cells, and basophils) produce the pro-inflammatory type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5, which drive type 2 inflammation (Citation4,Citation10–12). These three cytokine mediators have overlapping roles (Citation12):

IL-4 initiates T-cell differentiation toward the Th2 subtype and induces production of type 2-associated cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-5—this creates a positive feedback loop

IL-4 and IL-13 mediate B-cell activation, isotype switching and IgE production. They also play a role in fibrosis, airway remodeling, epithelial barrier dysfunction, FeNO production (Citation13,Citation14), and in eosinophil (EOS) trafficking to sites of inflammation

IL-13 mediates goblet cell hyperplasia, airway smooth muscle contractility, and mucus over production

IL-5 mediates EOS differentiation in the bone marrow, survival and mobilization, and migration from bone marrow to the blood

Biomarkers of T2 inflammation

Type 2 inflammation in asthma is associated with a range of elevated biomarker levels. These elevated biomarkers, which include higher blood EOS, higher serum IgE levels, and/or higher exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) levels, are key clinical indicators of type 2 inflammation (Citation1,Citation8).

Biomarker data can further define T2 asthma. Specifically, elevated IgE is indicative of allergic asthma when asthma symptoms are driven by allergen exposure, while elevated IgE and blood EOS is indicative of allergic/eosinophilic asthma (or type 2 asthma); additionally, elevated EOS and/or FeNO may indicate type 2 asthma.

The 2019 GINA guidance recognizes T2 inflammation and associated biomarkers. Specifically, GINA provides guidance for characterizing T2 inflammation in severe patients to determine eligibility for add-on biologic therapy; GINA defines T2 inflammation as (Citation1):

Blood EOS ≥150/μL and/or

FeNO ≥20 ppb and/or

Sputum EOS ≥2% and/or

Asthma is clinically allergen-driven and/or

Need for maintenance oral corticosteroids

T2 inflammation comorbidities

T2 inflammation is the pathophysiology behind several other conditions, some linked with more severe asthma and a greater burden of disease (see ).

Table 1. T2 inflammation comorbidities.

Asthma exacerbations are more likely in people with comorbid T2 inflammatory disease, and especially those with severe asthma and with upper airway comorbidities, such as rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) (Citation18,Citation19).

In an analysis of 118,981 UK patients with actively-treated asthma (Citation18), CRSwNP, rhinitis, and eczema were independent predictors of future asthma exacerbations.

The Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) analyzes large cohorts of people to look into clinical phenotypes and molecular mechanisms of asthma (Citation20). An analysis of 709 participants in the SARP-3 study (including 187 children) found chronic sinusitis was significantly associated with exacerbation frequency (Citation19).

Although there is currently a lack of evidence—especially in emerging markets—on asthma patient profiling, awareness of the impact of T2 inflammation and managing the associated comorbidities could play a role in improving asthma control for many patients.

Study objectives

Based on the lack of evidence on asthma patient profiles in emerging markets, the objective of this manuscript is to characterize patients with severe asthma based on measures of disease severity, patient exacerbation history and phenotyping. Improved understanding of the different profiles of patients with severe T2 asthma could support personalized treatment approach.

The data reported here is a subanalysis related to uncontrolled severe asthma patients from a 2018 survey conducted among physicians treating asthma patients regardless of severity level across eight countries. The manuscript aims to develop point-in-time patient profiles to characterize severe asthma. Aspects of asthmatic patient profiles included exacerbation history, T2 inflammation biomarkers and T2 inflammation comorbidities to align with the current understanding of T2 asthma and the 2018 GINA guidance (the most recent version at the time of the survey).

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of physicians treating asthma patients ages 12 years and older was conducted in eight countries: Mexico (MEX), Brazil (BRA), Colombia (COL), Russia (RUS), Turkey (TUR), Saudi Arabia (KSA), United Arab Emirates (UAE), and China (CHN) during a period from June 6, 2018 to July 18, 2018. The physician sample size was selected to represent the population size of their respective countries. No statistical hypotheses was to be tested in this analysis, as the purpose of the study is to provide a descriptive analysis of the severe asthma population. The research was carried out in compliance with local codes of conduct for market research (Citation21).

Survey design

The survey collected two types of information: declarative data reported from the physician perspective and data from patient medical charts, extracted and reported by the physicians.

First, physicians were asked to describe their asthma patient populations and treatment approaches for patients ages 12 years and older. This declarative portion of the survey included questions about the patient treatment regimens (including biologics, if applicable), GINA Step, control of asthma (pre- and post-physician exposure to the 2014 ERS/ATS definition), ambulance calls (Russia only), emergency room (ER) visits (all countries except Russia), hospitalizations, and T2 comorbidities. Physicians also provided their perspectives on treatment goals, patient OCS use, and considerations for biologic therapy.

Physicians were then instructed to complete patient record forms using medical chart data from a convenience sample of their six most recent asthma patients ages 12 years or older taking prescription medication regardless of the level of asthma severity, T2 inflammation profile or biomarkers. Physicians were asked to select 1–3 records for patients with uncontrolled asthma on a medium or high-dose ICS regimen, and the remaining records could be from any patient meeting the aforementioned criteria. Physicians were instructed to conduct data collection from their six most recent asthma patients without specification in order to avoid any selection bias. Specific information reported by physicians using patient medical charts is summarized in .

Table 2. Summary of main patient data reported by physicians.

Table 3. Physician demographics.

Table 4. Patient demographics: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) asthma patients age 12+.

Table 5. Asthma severity: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 12+.

Following GINA guidance regarding the importance of phenotyping patients with a confirmed diagnosis of severe asthma, this manuscript will focus on a subanalysis of the patient data for the subset of severe patients, defined as having uncontrolled asthma and receiving high-dose ICS plus at least one controller. The objective was to assess asthma severity (considering background therapy and GINA step), exacerbation history (including associated hospitalizations and ER visits/ambulance calls), and asthma phenotyping based on T2 inflammation biomarkers and comorbidities to provide a point-in-time characterization of severe asthma patients using real world evidence.

Survey participants

Participants were selected from a pool of pulmonologists, allergists, immunologists, and general practitioners. Each country physician sample was determined by local treatment patterns to ensure inclusion of physicians who routinely see, treat and manage asthma patients. Participating physicians had to spend at least 50% of their professional time performing direct patient care and see a minimum of 25 asthma patients age 12+ years per month with at least 50% of these patients being treated with prescription medication. Physicians were also required to have been practicing between 4 and 30 years. Physicians were excluded from participation if any member of their household was affiliated with a pharmaceutical manufacturer or if they were currently participating in a clinical trial as an investigator or patient.

Analysis

The analysis was conducted at the individual country and global level. Categorical variables were reported with the number and percentage of patients for each category. Continuous variables were reported with mean and standard deviation (SD).

Results

A total of 550 physicians completed the survey and filled out 3,300 patient record forms. Key findings were reported for the subset of patient record forms for uncontrolled asthma patients on high-dose ICS with at least one controller, which represented 27% (n = 876) of the overall cohort. Physician and patient demographics are reported in and , respectively. Supplementary data tables provide further data on the uncontrolled, medium-dose ICS population, and the adult population only (ages 18 years and older).

Key Findings

Asthma severity

Overall, physicians reported that 11% of patients were considered to be chronic OCS users. In comparison, a higher proportion of patients in Turkey (17%) were deemed to be chronic OCS users ().

The majority of patients overall were classified by physicians as being on GINA Steps 4 or 5 (72%) which aligned with the current GINA guidance at the time of the survey (2018). Per GINA 2018, treatment with high-dose ICS alone or medium dose plus a second controller could be considered as GINA Step 3 or higher (Citation22). However, physicians classified 5% of patients as being on GINA Steps 1 or 2 which indicated some discordance between physician-reported GINA Step and severity considering the current treatment regimen.

ACT and ACQ scores to assess more broadly the level of asthma control were reported in a limited number of patients, respectively, 46% and 19%. Overall patients had a poor level of asthma control with a mean ACT and ACQ score of 16.5 and 2.7, respectively.

Exacerbation history

The majority of overall patients (96%) had experienced at least one exacerbation regardless of severity in the past 12 months. Among these patients, the mean (SD) number of exacerbations experienced per patient over the past 12 months was 4.1 (4.8). Additionally, 76% of these patients had at least one exacerbation that required hospitalization, and the mean (SD) number of exacerbations requiring hospitalization per patient in the past 12 months (among patients who experienced at least one exacerbation) was 1.9 (2.5) ().

Notably, patients in Russia and China experienced a mean (SD) of 5.0 (6.0) and 6.6 (5.8) exacerbations respectively, which was greater than the global average. Moreover, Chinese patients experienced a greater mean (SD) number of exacerbations that required hospitalization [4.9 (4.4)].

Overall, 89% of patients required an ER visit at least once in the previous year and the mean (SD) ER visits per patient was 3.7 (4.8)Footnotei.

Russian and Chinese patients required a mean (SD) of 5.2 (5.7) and 6.3 (7.9) ER visits respectively, which were greater than the overall study population value.

Asthma phenotyping

Physicians extracted and reported their patients’ most recent biomarker test results when available in the medical charts; blood EOS level, FeNO measurement and IgE level was reported for 48%, 7%, and 57% of patients, respectively.

Overall, the mean (SD) EOS level among all patients who had available EOS test results was 203.0 (265.9) cells/µL; 40%, 31%, and 25% of patients had EOS ≥150, 300, and 400 cells/µL, respectively. Patients in Mexico and China had mean (SD) EOS levels of 376.2 (332.1) cells/µL and 459.3 (310.6) cells/µL, respectively, which were greater than the overall study population value. Additionally, higher proportions of patients in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, and China were represented by some EOS subgroups as compared with overall data (see ).

Table 7. Biomarker-based phenotypes: Uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) asthma patients age 12+.

Mean (SD) FeNO measurement across all patients was 90.7 (52.3) ppb; 98% and 95% had FeNO of 20 and 25 ppb, respectively. Data at the country-level was limited, with the exception of China.

Levels of total IgE were assessed as a proxy for allergy-driven asthma. At the overall study population level, mean (SD) IgE was 437.1 (730.6) IU/mL; 91% of patients had IgE levels within the range of IgE 30 − 1500 IU/mL.

Additional data on biomarker subgroups are summarized in .

The majority of patients had at least one of three T2 inflammation comorbidities assessed (65%)—atopic dermatitis (AD), CRSwNP, allergic rhinitis (AR). Higher proportions of patients in Russia, Turkey, and China had no T2 comorbidities versus the overall study population (see and ).

Figure 1. T2 inflammation comorbidities: Uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ >1 controller) patients age 12+. *AD = atopic dermatitis; CRSwNP = chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps; AR = allergic rhinitis.

Table 8. T2 inflammation comorbidities: Uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 12+.

Discussion

This analysis sought to characterize uncontrolled, severe asthma patients age 12 years or older across eight countries considering GINA guidance outlining indicators of T2 inflammation. Physicians reported data from a convenience sample of their six most recent asthma patients ages 12 years or older taking prescription medication. While they were asked to include 1 to 3 patients on a medium or high-dose ICS regimen, selection was not based on the patient’s T2 inflammation profile or biomarkers. The subanalysis focusing only on severe asthma patients showed a high burden of factors associated with T2 inflammation. Specifically, according to the 2019 GINA guidance for recognizing potential T2 inflammation, many patients included in the survey with EOS lab data recorded (n = 420) can be classified as having T2 inflammation as 40% had EOS ≥150/µL. Among all patients with available FeNO lab data (n = 65), 98% had FeNO ≥20 ppb. With IgE data as proxy for allergy-driven asthma, 91% of all patients with available IgE lab data (n = 498) had IgE 30 − 1500 IU/mL. Finally, chronic use of OCS (used as a proxy for maintenance OCS) was reported in 11% of all patients included in the survey.

Chronic OCS treatment and treatment on biologics may have had an impact on biomarker levels; however, the purpose of this study was to look at all severe asthma patients being treated at a specific point in time, not look at the variation in biomarker levels over time with different treatments. Additionally, the respective populations of these treatment groups were low, as 11% of patients use chronic OCS, and 15% of patients use a biologic add on, limiting the potential impact of medications on the interpretation of biomarker levels.

Type 2 inflammation comorbidities such as allergic rhinitis (AR), CRSwNP and atopic dermatitis (AD) were observed in respectively 59% (36% AR only), 17% (4% CRSwNP only), and 20% (4% AD only) of the overall population. These findings are in line with current published data (Citation23). Discordance between patient treatment regimen and physician-reported disease severity in terms of GINA Step was noted. This discrepancy indicates either a misinterpretation of asthma severity when using GINA Steps definitions as per treatment guidance versus physician interpretation of this guidance or an error in reporting.

There were a limited number of patients with reported data on asthma control using ACT or ACQ score, suggesting that assessment of level of control with these tools is limited in clinical practice or the data has not been reported.

Use of biologics was limited, ranging from 2% (KSA) to 24% (CHN). This could be due to limited access to biologics at the time of the study; omalizumab was available across all countries, while mepolizumab was available in four countries (MEX, RUS, UAE, and KSA) and reslizumab was only available in one country (RUS).

Limitations

There are limitations to this analysis that should be considered alongside the results. Patient data was reported by physicians who were instructed to extract data from medical charts as part of a survey and no confirmatory testing was conducted to validate these data. Also, comorbidities were physician or patient-reported and were not corroborated with claims data. Patient ACT/ACQ scores and biomarker lab values were reported for patients that had this information available in their medical records upon physician review and extraction. Additionally, data availability reflects real-life practice and variability in treatment guidelines. Furthermore, FEV1 tests were not always performed, which may have been impacted by a lack of facilities capable of performing spirometry in certain countries and regions. Biomarker data was also very limited for some countries; it is possible that blood EOS level testing, IgE level testing and FeNO measurement is not performed regularly for asthma patients in some countries. In particular, FeNO data was limited. The FeNO test is relatively new and lack of reimbursement may be a barrier to its adoption. Additionally, FeNO measurement was not included in the GINA guidance available at the time of the survey (2018); however, the most recent GINA guidance (2019) recommends the evaluation of FeNO as it can further support characterization of T2 inflammation and may also be a predictive factor of response to some T2 inflammation-targeted treatments. With regards to EOS testing, while parasitic infections such has helminthic infections, have a decreasing prevalence worldwide, it may have a significant presence in developing countries. These infections can stimulate Type 2 helper cells (Th2) immune response with up-regulation of cytokines IL-4-, IL-5-, and IL-13 mediated IgE and EOS (Citation24). Where relevant, physicians may test for parasitic infection and treat if present before commencing type 2 targeted treatment (Citation1).

Conclusions

The data provides an increased understanding of the different phenotypes and endotypes among severe, uncontrolled asthma patients with T2 inflammation. The increased understanding of severe asthma patient profiles can support the development of personalized treatment approaches. Characterization of T2 asthma has been specified in the 2019 GINA guidance and key indicators such as blood EOS, FeNO, allergen-driven asthma and OCS dependency should be considered. Multiple comorbidities related to T2 inflammation such as CRSwNP and moderate to severe atopic dermatitis should also be considered when determining eligibility for biologic add-on therapy as per the 2019 GINA guidance. This survey showed that 65% had at least one of three T2 inflammation comorbidities assessed (65%)—atopic dermatitis (AD), CRSwNP or Allergic rhinitis (AR). Use of biomarkers such as IgE or blood eosinophils are quite common, but FeNO data was limited despite its role to define type 2 asthma status. Discrepancies between treatment-defined asthma severity and physician perceived severity based on GINA classifications suggest there may be room to improve the understanding of asthma severity as defined per GINA Step definitions as well as asthma control assessment in clinical practice.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.9 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors wish to report the following conflicts of interest: Irina Kosoy and William Derrickson are paid consultants of Sanofi, sponsor of the research. Elisheva Lew is an employee of Sanofi, sponsor of the research. Olivier Ledanois is an employee of Sanofi, sponsor of the research.

Table 6. Exacerbation: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 12+.

Table A4. Biomarker-based phenotypes: Uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) asthma patients age 18+.

Table A5. T2 inflammation comorbidities: Uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 18+.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

Notes

i Russia reported ambulance calls due to exacerbations while all other countries reported emergency room visits due to exacerbations. For the sake of simplicity, this manuscript uses ambulance calls as a proxy for ER visits.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2019). Available from: https://ginasthma.org/severeasthma/ [last accessed 3 November 20 2019].

- Kim H, Ellis AK, Fischer D, Noseworthy M, Olivenstein R, Chapman KR, Lee J. Asthma biomarkers in the age of biologics. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2017;13:48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-017-0219-4.

- Walter MJ, Holtzman MJ. A centennial history of research on asthma pathogenesis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32(6):483–489. doi:https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.F300.

- Gauthier M, Ray A, Wenzel SE. Evolving concepts of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(6):660–668. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201504-0763PP.

- Seys SF, Scheers H, Van den Brande P, Marijsse G, Dilissen E, Van Den Bergh A, Goeminne PC, Hellings PW, Ceuppens JL, Dupont LJ, et al. Cluster analysis of sputum cytokine-high profiles reveals diversity in T(h)2-high asthma patients. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0524-y.

- Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Arron JR, Koth LL, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–395. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC.

- Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, Korenblat PE, Parsey MV, Arron JR, Harris JM, Scheerens H, Wu LC, Su Z, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1088–1098. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1106469.

- Peters MC, Mekonnen ZK, Yuan S, Bhakta NR, Woodruff PG, Fahy JV. Measures of gene expression in sputum cells can identify TH2-high and TH2-low subtypes of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):388–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.036.

- Schleich F, Brusselle G, Louis R, Vandenplas O, Michils A, Pilette C, Peche R, Manise M, Joos G. Heterogeneity of phenotypes in severe asthmatics. The Belgian Severe Asthma Registry (BSAR). Respir Med. 2014;108(12):1723–1732. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.007.

- Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma-present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(1):57–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3786.

- Chung KF. Targeting the interleukin pathway in the treatment of asthma. Lancet. 2015;386(9998):1086–1096. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00157-9.

- Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4624.

- Spahn JD, Malka J, Szefler SJ. Current application of exhaled nitric oxide in clinical practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(5):1296–1298. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.002.

- Saito J, Gibeon D, Macedo P, Menzies-Gow A, Bhavsar PK, Chung KF. Domiciliary diurnal variation of exhaled nitric oxide fraction for asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):474–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00048513.

- Tan BK, Chandra RK, Pollak J, Kato A, Conley DB, Peters AT, Grammer LC, Avila PC, Kern RC, Stewart WF, et al. Incidence and associated premorbid diagnoses of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(5):1350–1360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.002.

- deShazo RD, Kemp SF. Allergic rhinitis: Clinical manifestations, epidemiology, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/allergic-rhinitis-clinical-manifestations-epidemiology-and-diagnosis [last accessed 25 January 2018].

- Marcus P, Arnold RJG, Ekins S, Sacco P, Massanari M, Stanley Young S, Donohue J, Bukstein D, on behalf of the CHARIOT Study Investigators. A retrospective randomized study of asthma control in the US: results of the CHARIOT study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(12):3443–3452. doi:https://doi.org/10.1185/03007990802557880.

- Blakey JD, Price DB, Pizzichini E, Popov TA, Dimitrov BD, Postma DS, Josephs LK, Kaplan A, Papi A, Kerkhof M, et al. Identifying risk of future asthma attacks using UK medical record data: A respiratory effectiveness group initiative. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):1015–1024e8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2016.11.007.

- Denlinger LC, Phillips BR, Ramratnam S, Ross K, Bhakta NR, Cardet JC, Castro M, Peters SP, Phipatanakul W, Aujla S, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program-3 Investigators, et al. Inflammatory and comorbid features of patients with severe asthma and frequent exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(3):302–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201602-0419OC.

- Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE, Lee GB. Understanding asthma phenotypes, endotypes, and mechanisms of disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(2):219–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8712-1.

- The ICC/ESOMAR Code. Available from: https://www.esomar.org/what-we-do/code-guidelines [last accessed 06 December 2019].

- Global Initiative for Asthma. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2018). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention [last accessed 16 January 2020].

- Bouquet J, et al. Allergy. 2008;638–160.

- Ayelign B, Akalu Y, Teferi B, Molla M, Shibabaw T. Helminth induced immunoregulation and novel therapeutic avenue of allergy. J Asthma Allergy. 2020;13:439–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S273556.

Appendix A

Table A1 Patient demographics: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) asthma patients age 18+.

Table A2. Asthma severity: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 18+.

Table A3. Exacerbation: uncontrolled, high-dose ICS (+ ≥1 controller) patients age 18+.