Abstract

Objective

To investigate effectiveness of two different educational methods to improve inhaler techniques in patients with prior diagnosis of asthma, hospitalized with a non-asthma-related diagnosis.

Methods

We undertook a real-world, opportunistic quality-improvement project. Inhaler technique in hospitalized patients with prior diagnosis of asthma was assessed in two cohorts over two 12-week cycles using a standardized device-specific proforma of seven-step inhaler technique, classed: “good” if 6/7 steps achieved; “fair” if 5/7 compliant; “poor” for others. Baseline data was collected in both cycles. Cycle one involved face-to-face education by a healthcare professional; cycle two involved additional use of an electronic device to show device-specific videos (asthma.org.uk). In both cycles, patients were reassessed within two days for improvements and the two methods compared for effectiveness.

Results

During cycle one 32/40 patients were reassessed within 48 h; eight lost to follow-up. During cycle two 38/40 patients were reassessed within 48 h; two lost to follow-up During cycle one, two and 12 had good/fair baseline technique respectively, and 26 poor. Most commonly missed steps were no expiry check/not rinsing mouth after steroid use. On reassessment 17% patients improved from poor to fair/good. During cycle two, initial technique assessment identified: 23 poor; 12 fair; five good. Post-videos, 35% of patients improved from poor to fair/good. Proportion of patients improving from poor to fair, or poor/fair to good increased in cycle two vs one (52.5% vs 33%).

Conclusion

Visual instruction is associated with improved technique compared to verbal feedback. This is a user-friendly and cost-effective approach to patient education.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases and responsible for approximately 1 in 250 deaths worldwide (Citation1). Inhaled medications remain the mainstay of chronic stage treatment. This is due to direct delivery to the airways with rapid onset time with minimal dosing, as well as practicality with the use of portable and compact inhaler devices (Citation2,Citation3). Poor inhaler technique has been recognized as a frequently encountered issue in treatment optimization, due to less medication being deposited in the airway (Citation4,Citation5).

Due to the significant morbidity and mortality caused by poorly controlled asthma, patient education and optimization of inhaler provision and technique remains a global priority (Citation6). Good management with inhaled medications leads to greater disease control and quality of life. However, their use may be limited by, for example, poor coordination (exacerbated by comorbid conditions such as poorly controlled arthritis, disabling stroke or history of memory impairment) or poor understanding of how to use the device, especially if multiple types are prescribed to a single individual (Citation7). A Cochrane Review of interventions to improve inhaler technique in asthma found there to be marked variation in how inhaler technique is addressed in clinical practice, with most interventions failing to yield consistent or important benefits (Citation2). This review also highlighted that it is consistently recommended that clinicians check inhaler technique regularly, but there is no guidance on how this is best achieved, and how to effectively intervene in cases of inadequate technique. A recent study has examined the involvement of the multidisciplinary team (community pharmacists and pulmonologists) (Citation8). However, few studies have comprehensively examined interventions to optimize inhaler use and reduce error (Citation9).

In our district general hospital, Inhaler techniques have been regularly checked in patient with asthma admitted with an exacerbation of their disease, albeit not in those presenting with non-asthma related conditions to the acute unselected medical take. We undertook a two-stage quality improvement study to opportunistically assess inhaler technique in patients with asthma admitted acutely with non-asthma related conditions and assess two methods of educational intervention designed to improve technique.

Methods

This study was undertaken over two subsequent 12-week phases (i.e. 12 weeks per cycle) in two separate cohorts, with 40 patients recruited to each phase. A standardized device-specific proforma of seven-step technique was produced, based on guidance from British Thoracic Society and Asthma UK (Citation10). This was used as the gold-standard against which patient inhaler technique was assessed throughout the study.

Baseline data was obtained from patients during both cycles. Patients with a prior diagnosis of asthma using inhaled medication were identified consecutively via electronic health records from all patients admitted via the acute unselected medical take. Inclusion criteria were: patients 18 years or older; with a clinician-confirmed diagnosis of asthma prescribed at least one inhaler; and the primary reason or diagnosis on acute admission to hospital was not an exacerbation of asthma. Patients were only recruited if deemed having mental capacity to engage with the assessment of inhaler technique. Exclusion criteria were children (under 18 years old) and/or admitted acutely due to their asthma.

In both phases, patients were approached by a trained clinician and had inhaler technique assessed against the gold-standard. Technique was graded as follows: good if at least six steps achieved; fair if at least five steps achieved; poor if one to four steps achieved. Type of inhaler device and details of missed steps were recorded.

Following the first assessment, an intervention to improve technique was performed in each of the two cohorts. During phase one, the clinician provided verbal instructions on how to better use the inhaler device. During phase two, based on feedback and results from phase one, patients viewed device-specific videos on how to use their inhaler on the Asthma UK website (Citation10). Technique was reassessed within 48 h and graded as above.

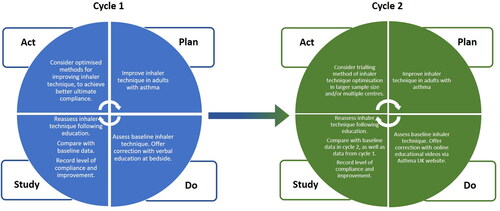

Summary of our methodology is available in , which is a “Plan-Do-Study-Act” format as per the convention for quality improvement studies.

Figure 1. Schematic analysis of “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycles for phases 1 and 2 of this quality improvement study, respectively.

Patient demographics and comorbidities were collated. Direct statements were also taken and recorded from patients on their experience of the interventions.

Subjects and data analysis

Patients with asthma were opportunistically recruited to the study using a consecutive sampling approach, on admission under the general medicine team. Recruitment took place for a period of two months in each cycle, or until a total of 40 patients had been reached in one cycle (if earlier than two months). This sample size was reflective of the number of patients with a diagnosis of asthma on at least one inhaler admitted to our local hospital for a non-asthma-related condition. No patients were missed in the consecutive sampling process, other than those both admitted and discharged out of hours.

Descriptive statistics were collated with regards to basic demographics and numbers of steps completed on assessment and re-assessment in each of the two cycles. The mean number of steps performed was compared before and after intervention in each of the two cycles, as well as assessing improvement from poor to fair, poor to good and fair to good, specifically. Chi-Square test was used to further compare the level of improvement following intervention between the two cycles.

Results

In each phase, 40 patients were recruited ( and Citation2). The average age of patients recruited to phase one and two was 62.7 (SD 18.6) and 62.5 years (SD 19.5) respectively. The majority of patients in both cycles was female (70% in cycle 1;75% in cycle 2). With regards to smoking status, in cycle 1, 17.5% were current smokers, 40% ex-smokers and 42.5% never smokers. In cycle 2, 7.5% were current smokers, 35% were ex-smokers and 57.5 were never smokers. All patients across cycles 1 and 2 were of Caucasian ethnicity.

Table 1. Phase one: Patient demographics and outcomes from inhaler checks, before and after intervention.

Table 2. Phase two: Patient demographics, outcomes and comments from inhaler checks, before and after intervention.

During phase one, 80% of patients were reassessed within 48 h, with eight lost to follow-up due to early discharge (n = 7) or transfer to another hospital (n = 1). During phase two 95% of patients were reassessed within 48 h, with two lost to follow-up. Across both phases, 12 patients had comorbidities which could adversely affect their technique e.g. dementia, disabling stroke, poorly-controlled inflammatory arthritis. Summary of all results are available in and Citation2.

During phase one, 65% of patients had poor inhaler technique at baseline check, 30% fair, and 5% good. On average, each patient was on two different inhalers with Salbutamol and Beclomethasone being the most frequently prescribed. The most commonly missed steps were not checking device expiry date and not rinsing mouth after steroid use. Two patients completed all steps with no errors, which was in contrast to only two self-identifying their techniques as being “suboptimal” prior to our intervention. On reassessment, 17% of patients improved from poor to fair or good, or fair to good. Seven patients achieved all seven steps on reassessment and three had no recollection of the consultations. The average number of steps performed increased 2.9 to 5.1 (Chi-Square test p < 0.05).

During phase two, 57% of patients had poor inhaler technique at baseline check, 30% fair, and 12% good. After viewing a device-specific video on use of their inhaler on the Asthma UK website, 35% of patients improved from poor to fair or good, or fair to good. The average number of steps performed increased from 3.9 to 5.2 (Chi-Square test p < 0.05). As for phase one, seven patients achieved all seven steps on reassessment. However, the proportion of patients improving from poor to fair, or poor/fair to good, increased in phase two (verbal instructions with videos) compared to phase one (verbal instructions alone) (52.5% vs 33%).

With regards to comments taken directly from patients, there was a demonstrable preference for the videos used during phase two, with patents describing them as “helpful,” “easy to understand,” “informative.” Patients also reported that they were able to learn specific steps of taking their inhaler that they had previously missed or had not realized their importance, e.g. “I sometimes wonder if the medicine is going in, but I will remember to tilt my head back and hold my breath after taking my inhaler.” Most patients felt that an acute admission is a good time to check inhaler technique as it is a quick and easy exercise provided the patient is not too unwell and has capacity to do so: “With time it is easy to forget instructions given regarding inhalers so the video was good for a reminder for me.”

Discussion

In this opportunistic educational study we have demonstrated that visual instruction (via videos) is associated with improved inhaler technique compared to verbal feedback when assessing and optimizing the use of inhalers in adults with asthma. This is novel study comparing interventions for an area of need which previous studies and reviews have highlighted as a cause of suboptimal asthma control leading to poor clinical outcomes.

Poor inhaler technique has been demonstrated as one of the most common reasons for suboptimal disease management in adults with asthma. Poor technique has a direct correlation with patients’ co-morbidities with higher chance of poorer technique in multi-morbid individuals (Citation4,Citation5). It is unclear whether there is an association between the place where the patient was initially taught their techniques (inpatient vs outpatient vs community) and the professional who delivered the teachings (physician, nurse or pharmacist) make any difference in achieving optimal technique. Nonetheless, a recent study comprising 140 patients with diagnosis of asthma or COPD demonstrated that increasing partnership between the pharmacists and chest physicians improve outcomes with inhaler techniques (Citation8). We have demonstrated improvements in inhaler technique, optimized through the use of freely available videos, in patients acutely admitted for non-asthmatic conditions. This is an opportunistic way by which to check inhaler technique in patients with asthma, harnessing a user-friendly, quick and cost-effective method.

Interventions to enhance inhaler technique fall broadly into three categories: technological interventions; educating the clinician; educating the patient (Citation9). Within these, the breadth of interventions available is so great that no individual method has been proven to improve technique and long-term outcomes. In our study, we were able to show the utility of opportunistic assessment of patients’ inhaler techniques during admission for a non-asthmatic problem. Generally, these patients are multimorbid and potentially at increased risk of asthma exacerbations. Furthermore, the reduction in face-to-face outpatient assessments in light of the COVID-19 pandemic makes it more imperative to address comorbidities such as asthma whilst in hospital for another reason.

We demonstrated some improvement in technique with verbal instruction, but an even greater improvement with the use of freely available online videos. Each video was approximately four minutes in length, leading to a total assessment time of under ten minutes. This is therefore a cost-effective and time-sensitive resource, which can be utilized globally and non-dependent on socioeconomic factors or language. Patient anecdotes demonstrate satisfaction with the intervention and overall interaction with the healthcare professional during the study.

Strengths of this study are a large sample size comprising patients of a broad age range and comorbidities, allowing assessment of these factors. Two separate interventions were trialed and allowing comparison between the two. The population surrounding our local hospital is homogenous with regards to ethnicity and socioeconomic status, allowing for reliable comparison of results. Our study was limited in that we were unable to test these interventions in those with conditions such as severe dementia or the acutely unwell due to lack of capacity. However, it would be expected, in the case of dementia patients, caregivers would undergo the training instead, potentially with the use of a delivery system, e.g. spacer. In the case of acutely unwell patients, interventions may be given later in the admission once the patient’s clinical condition improves. Patients who have had a cerebrovascular accident, leading to physical disability limiting their inhaler technique, would likely benefit from multidisciplinary input from specialist pharmacists, occupational therapists and stroke physicians for technique optimization. Additionally, patients who are not comfortable using the Internet may not be able to easily access the videos on discharge, should they wish to do so. However, to overcome this, printed screen-captures of key steps from the video were offered to these patients to take home.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have shown, in an opportunistically-recruited cohort of patients admitted to hospital with non-asthma-related conditions, that there are deficiencies in inhaler technique amongst patients with asthma. We have demonstrated that visual instruction (with the use of specialized videos) is associated with improved inhaler technique compared to verbal instruction alone. Consideration of comorbidities and involvement of the multidisciplinary team, including carers and family members, is vital in ensuring optimized use of inhalers and subsequent good asthma control. The use of online videos for optimization of inhaler technique is a user-friendly and cost-effective approach to patient education.

Declaration of interest

All authors mentioned do not have any declarations of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abdollahi M, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–1222.

- Cochrane Library Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Interventions to improve inhaler technique for people with asthma (Review) Interventions to improve inhaler technique for people with asthma (Review). 2022; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: www.cochranelibrary.com.

- Asthma | British Thoracic Society. Better lung health for all [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/.

- Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, Dunlop WCN, Heron L, Farrington E, Dekhuijzen R. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):10–20; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://respiratory-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y doi:10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y.

- Roche N, Aggarwal B, Boucot I, Mittal L, Martin A, Chrystyn H. The impact of inhaler technique on clinical outcomes in adolescents and adults with asthma: a systematic review. Respir Med [Internet]. 2022; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36063773/.

- Asthma [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/asthma.

- Vanoverschelde A, van der Wel P, Putman B, Lahousse L. Determinants of poor inhaler technique and poor therapy adherence in obstructive lung diseases: a cross-sectional study in community pharmacies. BMJ Open Respir Res [Internet]. 2021;8(1):e000823; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/8/1/e000823. doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000823.

- Gemicioglu B, Gungordu N, Can G, Yıldırım FIA, Doğan BSU. Evaluation of real-life data on the use of inhaler devices, including satisfaction and adherence to treatment, by community pharmacists in partnership with pulmonary disease specialists. J Asthma. 2022. doi:10.1080/02770903.2022.2144355.

- Price D, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Briggs A, Chrystyn H, Rand C, Scheuch G, Bousquet J, Inhaler Error Steering Committee. Inhaler competence in asthma: common errors, barriers to use and recommended solutions. Respir Med. 2013;107(1):37–46; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23098685/. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.09.017.

- How to use your inhaler | Asthma UK [Internet]; [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos/.