Abstract

Objective

Short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) overuse is associated with poor asthma outcomes; however, the extent of SABA use in Thailand is largely unknown. As part of the SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) III study, we describe asthma treatment patterns, including SABA prescriptions, in patients treated by specialists in Thailand.

Methods

In this observational, cross-sectional study, patients (aged ≥12 years) with an asthma diagnosis were recruited by specialists from three Thai tertiary care centers using purposive sampling. Patients were classified by investigator-defined asthma severity (per 2017 Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA] recommendations). Data on sociodemographics, disease characteristics, and asthma treatment prescriptions were collected from existing medical records by healthcare providers and transcribed onto electronic case report forms. Analyses were descriptive.

Results

All 385 analyzed patients (mean age: 57.6 years; 69.6% female) were treated by specialists. Almost all (91.2%) patients were classified with moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA treatment steps 3–5), 69.1% were overweight/obese, and 99.7% reported partially/fully reimbursed healthcare. Asthma was partly controlled/uncontrolled in 24.2% of patients; 23.1% experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the preceding 12 months. Overall, SABAs were over-prescribed (≥3 canisters/year) in 28.3% of patients. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), ICS/long-acting β2-agonists, oral corticosteroid (OCS) burst treatment, and long-term OCS were prescribed to 7.0, 93.2, 19.2, and 6.2% of patients, respectively. Additionally, 4.2% of patients reported purchasing SABA over the counter.

Conclusions

Despite receiving specialist treatment, 28.3% of patients were over-prescribed to SABA in the previous 12 months, highlighting a public health concern and the need to align clinical practices with current evidence-based recommendations.

Introduction

Asthma remains a common disease in Thailand, and according to the Global Asthma Report of 2022, Thailand ranks eighth in asthma mortality rates among low- and middle-income countries (Citation1). Consequently, the burden of asthma is high, with results from a survey of 400 patients with asthma in Thailand reporting that 17% had been hospitalized and 35% had an unscheduled emergency visit to a hospital or a physician’s clinic in the previous year (Citation2). This survey also revealed that asthma had a profound impact on patient well-being leading to a decline in productivity when asthma was at its worst (Citation2). Additionally, asthma imposes a considerable economic burden on the healthcare system in Thailand. Indeed, while the annual household income per capita in Thailand is $3322.8 (Citation3), the average annual asthma cost per patient in Thailand is reported to be ∼$600, with healthcare costs in patients with severe asthma being $71 higher than in those with mild/moderate asthma (Citation4).

The management of patients with asthma in alignment with evidence-based guidelines is essential to achieve and maintain symptom control and prevent exacerbations (Citation5). However, many patients continue to rely on the use of short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) for rapid relief from asthma symptoms, despite the fact that asthma is a disease of chronic airway inflammation and that SABAs have no inherent anti-inflammatory pharmacological properties (Citation6,Citation7). This is of particular concern since SABA overuse (≥3 canisters/year) is associated with an increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality (Citation8–11). Moreover, the purchase of ≥2 SABAs during the course of 1 year has been shown to correlate with poor asthma control as evaluated by patients (Citation12), with results from a recent study highlighting that the purchase of ≥3 types of all short-acting bronchodilators (SABA and anticholinergic inhalers and solutions) in one year should alert physicians to evaluate asthma control (Citation13). Therefore, following a landmark update in 2019, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) no longer recommends as-needed SABA without concomitant inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for patients aged ≥12 years; instead, GINA now recommends low-dose ICS-formoterol as the preferred reliever for adults and adolescents at GINA treatment steps 1 and 2, and patients prescribed ICS-formoterol maintenance therapy at GINA treatment steps 3–5 (Citation5). The Thoracic Society of Thailand first published asthma management guidelines in 1995, with the overall goal of improving asthma control in Thailand. To date, the general practice for treating patients with asthma in Thailand is per the GINA recommendations. Indeed, in 2019, the Thai Asthma Council and Association followed the updated GINA recommendations, initially recommending the use of SABA only with concomitant ICS and then removing SABA use altogether in 2020 (Citation14). However, despite the magnitude of the asthma burden in Thailand, little is known about the specific patterns of asthma medication use, particularly the prevalence of SABA use and overuse. As more patients seek clinical care for asthma, such information is essential to guide policy decisions and ensure the implementation of effective public health strategies for disease prevention and management.

The SABA use IN Asthma (SABINA) program was undertaken to describe the global extent of SABA use and its clinical consequences through a series of large observational cohort studies applying a harmonized approach to data collection, evaluation, and interpretation (Citation15). The SABINA International (III) arm of the program was conducted in 23 countries across Asia-Pacific, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Russia and used a standardized methodology that was designed to capture clinical information through electronic case report forms (eCRFs) to overcome the lack of robust national healthcare databases in many of the participating countries (Citation16). Here, we report results from the SABINA III Thailand cohort to provide real-world evidence on asthma treatment practices in patients under specialist care in the country.

Methods

Study design

This was an observational, cross-sectional study conducted at three sites distributed across Thailand. For all three study sites, patient recruitment occurred between November 2019 to mid-January 2020. The three study sites were academic tertiary care centers located in different geographical regions of Thailand: (i) the Maharaj Nakhon Chiang Mai Hospital, a medical school based in the North of Thailand; (ii) the Maharaj Nakhon Ratchasima Hospital, the largest regional hospital in the North East of Thailand under the Ministry of Public Health; and (iii) the Hatyai Hospital, a regional hospital under the Ministry of Public Health, in the South of Thailand. The study sites were selected on the basis that they were central healthcare hubs for their respective regions and had the necessary facilities to conduct the study. The objectives of the study were to describe the demographic and clinical features of the asthma population by asthma severity and to estimate SABA and ICS prescriptions per patient. The study sites were selected using purposive sampling with the aim of obtaining a sample representative of asthma management within each participating site by a national coordinator. The coordinator provided advice on the different types of centers (primary care centers, different types of hospitals, and geographical distribution), and facilitated the selection of the investigators (pulmonologists/respiratory physicians/general physicians with expertise in Good Clinical Practice). During the recruitment period, to minimize selection bias, patients were identified consecutively, with those meeting the eligibility criteria and providing consent, entered into the study. Prespecified patient data on exacerbation history, comorbidities, and asthma medication prescriptions were collected from existing medical records by healthcare providers (HCPs) and collated into eCRFs during a single study visit at each site. The detailed methodology for SABINA III has been described previously (Citation16). The study was conducted in accordance with the study protocol, local ethics committee guidelines, and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University; the Research Ethics Committee of Hat Yai Hospital (REC-HY); and the Ethics Committee of Maharat Nakhon Ratchasima Hospital.

Study population

Patients aged ≥12 years with a physician-documented diagnosis of asthma, ≥3 prior consultations with the same HCP to exclude those patients seen by several different physicians, and medical records containing data for ≥12 months before the study visit were enrolled (Citation16). Patients were excluded from the study if they had (i) other chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or (ii) an acute or chronic condition that, in the investigators’ opinion, would limit the patient’s ability to participate in the study. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients or legal guardians (for patients aged <18 years).

Variables and outcomes

Patients were categorized by their SABA and ICS prescriptions, as previously described (Citation16). SABA prescriptions were recorded and categorized as 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–12, and ≥13 canisters, with over-prescription defined as prescription of ≥3 SABA canisters in the 12 months prior to the study visit (Citation8,Citation9,Citation16). ICS canister prescriptions in the previous 12 months were recorded and categorized according to the prescribed average daily dose as low, medium, or high (Citation5).

Other key variables included sociodemographic characteristics (age, comorbidities, body mass index [BMI], smoking status, number of comorbid conditions, education level [primary or secondary school, high school, or university and/or post-graduate education], healthcare reimbursement status [not reimbursed, partially reimbursed, or fully reimbursed], and practice type [primary or specialist care]). Patients were also categorized based on asthma characteristics, such as investigator-classified asthma severity; in this regard, physicians were guided by GINA 2017 (Citation5) treatment steps (GINA steps 1–2, mild asthma; GINA steps 3–5, moderate-to-severe asthma), and directed to the study protocol, with information also provided via a pop-up window in the eCRF. The number of severe exacerbations in the preceding 12 months was documented, defined as a deterioration in asthma requiring hospitalization, emergency room treatment, or intravenous corticosteroids/oral corticosteroids (OCS) for ≥3 days or a single dose of an intramuscular corticosteroid, based on the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society recommendations (Citation17). Asthma symptom control was evaluated during the study visit using the GINA 2017 assessment for asthma control (Citation5) and categorized as well-controlled, partly controlled, and uncontrolled.

Prescription data for asthma medications, including ICS monotherapy, ICS fixed-dose combinations with long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), short-course OCS (defined as a short course of intravenous corticosteroids or OCS administered for 3–10 days, or a single dose of an intramuscular corticosteroid to treat an exacerbation), long-term OCS (defined as any OCS treatment for >10 days), and antibiotics prescribed for asthma, were collected. Data for SABA purchases over-the-counter (OTC) from a pharmacy without a prescription in the previous 12 months were obtained directly from patients at the study visit and entered in the eCRF by the investigator.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to characterize patients according to baseline demographics and clinical characteristics. Continuous variables were summarized by the number of non-missing values, mean (standard deviation [SD]), and median (range). Categorical variables were summarized by frequency counts and percentages. No statistical testing or comparisons were performed.

Results

Patient disposition

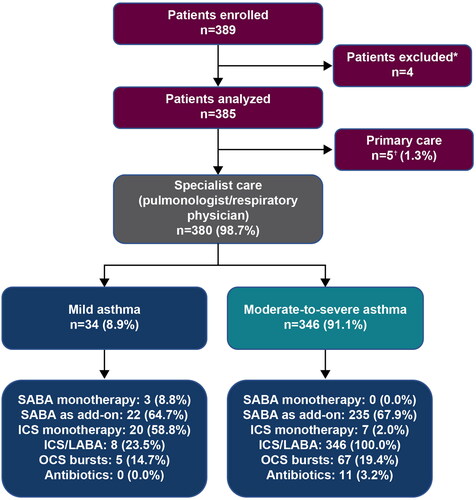

Of 389 patients enrolled, four were excluded due to an asthma duration of <12 months. Therefore, a total of 385 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 44.2% were recruited from the Maharaj Nakhon Chiang Mai Hospital, 26.0% from the Maharaj Nakhon Ratchasima Hospital, and 29.9% from the Hatyai Hospital. All patients were recruited by specialists comprising pulmonologists/respiratory physicians; however, five patients were erroneously allocated to “primary care” and were therefore excluded from the analysis of asthma severity ().

Figure 1. Patient population by asthma severity in the SABINA III Thailand cohort. *Patients excluded had an asthma duration of <12 months. †Patients were erroneously classified under primary care. Note. One patient included in this analysis was aged <18 years. Patients could have been prescribed multiple treatments in the 12 months before the study visit. ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; LABA: long-acting β2-agonist; OCS: oral corticosteroids; SABA: short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA: SABA use IN Asthma.

Patient demographics and lifestyle characteristics

The majority of patients were female (69.6%), and most (81.3%) had no history of smoking (). The mean (SD) age of patients was 57.6 (13.6) years, with over half of all patients aged ≥55 years (60.3%). One patient was aged <18 years. The mean (SD) BMI was 25.3 (4.5) kg/m2, and according to the Asia-Pacific BMI classification (Citation18), 19.2% of patients were overweight and 49.9% were obese. Nearly half of all patients (47.8%) reported only primary and/or secondary school education, while almost a quarter had obtained high school (23.4%) or university and/or post-graduate education (24.7%). With the exception of one patient, all other patients reported either partial (42.3%) or full (57.4%) healthcare reimbursement.

Table 1. Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics stratified by asthma severity in the SABINA III Thailand cohort.

Disease characteristics

Overall, the mean (SD) duration of asthma was 10.3 (10.5) years. The majority of patients (91.1%) had investigator-classified moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA treatment steps 3–5), whereas 8.9% had mild asthma (GINA treatment steps 1–2); most patients were at GINA treatment step 3 (35.1%) or step 4 (52.5%) (). More than half of all patients (57.9%) had 1–2 comorbidities, and 5.2% had ≥5 comorbidities. Patients experienced a mean (SD) of 0.5 (1.2) severe asthma exacerbations in the 12 months preceding study initiation, with 23.1% having ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation. The level of asthma control was assessed as well-controlled in 75.8% of patients, whereas 14.8 and 9.4% of patients had partly controlled and uncontrolled asthma, respectively.

Table 2. Asthma characteristics stratified by investigator-classified asthma severity in the SABINA III Thailand cohort.

Asthma treatment prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit

Overall SABA prescription categorization

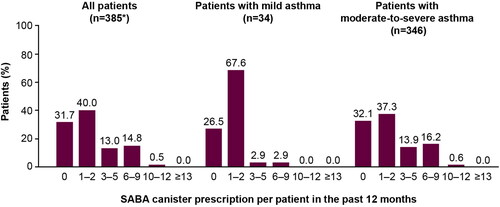

Among all patients, 28.3% were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months, defined as over-prescription (). Approximately, one-third of patients (31.7%) were not prescribed SABAs. A higher proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma than with mild asthma were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters (30.6 vs. 5.9%). Only one patient was prescribed nebulized SABA, with no patients prescribed oral SABA.

Figure 2. SABA prescription categorization in the 12 months before the study visit in the SABINA III Thailand cohort. *Five patients were erroneously classified under primary care and excluded from the analysis based on asthma severity (mild vs. moderate-to-severe). Note. One patient included in this analysis was aged <18 years. The category of patients classified as having zero SABA canister prescriptions included patients using non-SABA relievers, non-inhaler forms of SABA, and/or SABA purchased over the counter. SABA: short-acting β2-agonist; SABINA: SABA use IN Asthma.

SABA monotherapy

In total, only 0.8% of patients were prescribed SABA monotherapy, all of whom had mild asthma. These patients were prescribed a mean (SD) of 1.0 (0.0) SABA canisters in the preceding 12 months ().

Table 3. SABA prescriptions in the 12 months before the study visit in patients receiving SABA monotherapy and SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in the SABINA III Thailand cohort.

SABA in addition to maintenance therapy

Overall, 67.5% of patients were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy in the previous 12 months, with a mean (SD) of 3.3 (2.8) SABA canisters; 41.9% of these patients were prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters ().

SABA purchase without a prescription

In the 12 months before the study visit, 4.2% of patients reported purchasing SABA OTC, the majority of whom (93.8%) purchased 1–2 SABA canisters ().

Table 4. Patients who received SABA without a prescription in the 12 months before the study visit in the SABINA III Thailand cohort.

Maintenance medication

Overall, 7.0% of patients were prescribed ICS monotherapy, with a mean (SD) of 3.9 (2.2) ICS canisters in the previous 12 months; of these patients, 85.2 and 14.8% were prescribed low- and medium-dose ICS, respectively (). Meanwhile, 93.2% of patients, including all patients classified as having moderate-to-severe asthma, were prescribed ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations. Of these patients, more than half (58.7%) were prescribed medium-dose ICS, while 37.2 and 4.2% were prescribed low- and high-dose ICS, respectively ().

Table 5. Other categories of asthma treatment prescribed in the 12 months before the study visit in the SABINA III Thailand cohort.

Other asthma medications

In the preceding 12 months, 19.2% of patients were prescribed one or more OCS burst treatment and 6.2% were prescribed long-term OCS treatment (). In addition, 2.9% of patients, all of whom were diagnosed with moderate-to-severe asthma, were prescribed antibiotics for asthma.

Overall, 59.7% of patients were prescribed leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA), and 25.7% were prescribed xanthines in the 12 months before the study visit (). Additionally, long-acting muscarinic antagonists, monoclonal antibodies, and short-acting muscarinic antagonists/SABA were prescribed to 15.1, 1.6, and 1.0% of patients, respectively.

Asthma treatment prescriptions and exacerbations

When stratified by treatments prescribed in the 12 months prior, most patients (75%) prescribed long-term OCS experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation, followed by those prescribed OCS burst treatment (68.9%), antibiotics (63.6%), and SABA in addition to maintenance therapy (27.3%).

Discussion

This cross-sectional cohort study, conducted as part of the SABINA III study, provides real-world insights into asthma treatment practices at the specialist care level in Thailand. As achieved with some of the other SABINA cohorts (Citation19,Citation20), this study was intended to include a nationally representative sample of both primary care physicians and specialists; however, as observed in many other Asian countries included in SABINA III (Citation21–23), all patients from SABINA Thailand were recruited from specialist care. This lack of patient recruitment from primary care may be attributed to inherent challenges commonly encountered in conducting trials at a primary care level in Thailand, including the heavy caseload of primary care physicians, time constraints, health inequity, lack of resources, staff and training, and limited experience in clinical trial recruitment (Citation24–26).

Of concern, among all patients prescribed SABA, over a quarter (28.3%) were prescribed SABA in excess of current treatment recommendations (≥3 SABA canisters per year). These findings are in line with the country-aggregated SABINA III data from 24 countries, where SABA over-prescription was reported in 38% of patients (Citation16). Overall, more than two-thirds of all patients (67.5%) were prescribed SABA in addition to maintenance therapy, with 41.9% prescribed ≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months. In addition, 4.2% of patients reported purchasing SABA OTC in the preceding 12 months, although this was lower than anticipated given that SABAs are available for purchase without a prescription in Thailand. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the need to align clinical practices with current treatment recommendations and educate patients on effective self-management of asthma and the risks of SABA overuse. This is of particular importance since results from SABINA III indicated an association between high SABA prescriptions and poor clinical outcomes, with prescriptions of ≥3 SABA canisters (vs. 1–2 canisters) associated with increasingly lower odds of controlled or partly controlled asthma and higher severe exacerbation rates (Citation16).

Most patients in this Thai cohort were prescribed maintenance medication in the form of either ICS or ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations. While 7% of patients were prescribed ICS, consistent with 6.5% of patients being classified at GINA step 2, these patients were only prescribed a mean of 3.9 ICS canisters in the previous 12 months. This quantity suggests the potential underuse of ICS as one canister per month is considered good clinical practice. However, overall ICS coverage may be higher since 93.2% of patients were prescribed ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations, which was expected given that 89.9% of patients had moderate-to-severe asthma (GINA steps 3–5). These observations are in line with results from the 2016 Asia-Pacific Burden of Respiratory Diseases study, which enrolled 1000 patients with respiratory diseases across four sites in Thailand, and reported that ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations were the most commonly prescribed medication for asthma in Thailand, exceeding SABA prescriptions by ∼30% (Citation27). Taken together, these findings suggest that prescriptions for daily maintenance therapy in patients under specialist care in Thailand generally conformed to internationally recommended treatment and prevention guidelines and may account for the higher rates of asthma control compared with earlier surveys on asthma control in Thailand (Citation2,Citation28). These results may also be attributable to the success of the Easy Asthma Clinic Network that was developed to enhance the implementation of GINA guidelines in Thailand in 2004 (Citation29). These clinics, which are run by general physicians in hospitals throughout Thailand, aim to simplify asthma guidelines, facilitate teamwork, and emphasize the role of nurses and pharmacists. The Easy Asthma Clinics use a multidisciplinary approach comprising four main steps: (1) registration and asthma-control assessment by nurses; (2) evaluation and treatment by physicians; (3) follow-up appointments with nurses; and (4) asthma education, device education and adherence checks by clinically-trained pharmacists (Citation30). The implementation of the Easy Asthma Clinic Network has proven to be effective in reducing asthma-related hospitalizations and recently shown to facilitate controller use, resulting in an increasing trend of asthma control (Citation29,Citation30).

Our data also showed that a substantial number of patients were prescribed OCS burst treatment. While OCS bursts are typically used to treat exacerbations (Citation5), we observed that 31.1% of patients who were prescribed an OCS burst had not experienced any exacerbations in the previous 12 months. This may be partly due to physicians prescribing OCS medication as a standby in patients’ asthma action plans. Furthermore, it is possible that patients may be using OCS in place of inhaled medications to treat asthma symptoms. Indeed, previous reports have shown that in Asian countries, patients often prefer oral medication for asthma treatment (Citation31,Citation32). For instance, data from the Asia-Pacific Survey of Physicians on Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis study reported that 46% of physicians, including 29% of physicians surveyed in Thailand, strongly or somewhat agreed that patients prefer prescription of oral medications, as opposed to intranasal treatment, for asthma and allergic rhinitis (Citation31).

Of note, while the majority of patients (91.2%) had moderate-to-severe asthma, more than three-quarters of all patients (75.8%) in this study had well-controlled asthma. This suggests that the management and treatment of patients by specialists in Thailand may have improved over the past two decades, although patient populations across studies may not be entirely comparable (Citation2,Citation28). Furthermore, the level of asthma control in patients from Thailand is remarkably higher than that observed in the country-aggregated SABINA III data, where only 43.3% of patients had well-controlled asthma, although this finding is likely attributed to the fact that all patients in this Thai cohort were treated under specialist care, whereas 17.7% of patients in SABINA III were treated in primary care (Citation16). Results from SABINA Thailand are also very different from those of the 2015 Thailand Asthma Insight and Management (Thailand-AIM) survey, in which only 8% of adults and adolescents were classified as having controlled asthma, with 58 and 34% of patients having partly controlled or uncontrolled asthma, respectively (Citation2). However, in the Thailand-AIM survey, identification of patients did not involve accessing medical records or contacting healthcare providers, both of which could have impacted the results (Citation2). A possible explanation for the improved levels of asthma control observed in this Thai cohort is that nearly all patients reported full/partial healthcare reimbursement, a finding likely attributable to the fact that all patients were recruited from tertiary care centers by specialists. Nevertheless, even with the caveat that all patients were recruited from clinic/hospital sites by specialists, this finding is in stark contrast to the situation two decades ago, when healthcare services in Thailand were not subsidized. Indeed, the 2004 survey of asthma control in Thailand reported that a lack of healthcare reimbursement was the primary reason why 23.2% of patients had never consulted a physician (Citation28). This may explain the large proportion of patients who, as per GINA recommendations, received ICS/LABA fixed-dose combinations in this study despite the relatively high cost of this treatment. Nevertheless, despite the large proportion of patients with well-controlled asthma in our study, approximately one-quarter (23.1%) of patients experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the preceding 12 months, although this was lower than that reported from the country-aggregated SABINA III and Thailand-AIM studies, where 45.4 and 36% of patients experienced ≥1 severe asthma exacerbation in the previous year, respectively (Citation2,Citation16).

Although the results from this study imply improved asthma treatment in Thailand, it is noteworthy that all patients in the Thai cohort were treated by specialists with the expertise to provide optimal care for patients with asthma. Specialists are also more likely to be familiar with current asthma treatment recommendations and to prescribe ICS/formoterol as both maintenance and reliever therapy, which has been shown to substantially reduce exacerbations compared with ICS-containing maintenance plus as-needed SABA in patients with persistent asthma (Citation33). It is possible that the number of SABA prescriptions would have been greater if primary care physicians, who may be less familiar with asthma treatment recommendations, had participated in this study. Indeed, an assessment of 1440 patients with asthma from SABINA III who were treated at primary care centers reported that 44.9% of patients were over-prescribed SABAs, with 38.8% of patients experiencing ≥1 severe asthma exacerbations in the 12 months prior to the study visit (Citation34). Therefore, our cohort of patients likely represents a “better-case scenario,” with all patients being under specialist care and receiving either full or partial healthcare reimbursement. Nonetheless, the persistent exacerbation burden and large percentage of SABA over-prescriptions demonstrates the continued need for educational initiatives targeting both patients and physicians to improve asthma care.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. This study used purposive sampling which can be prone to research bias and was descriptive in nature with no statistical testing or comparisons performed. Prescribed asthma treatments were based on GINA 2017 recommendations, which were in place at the time this study was conceived and implemented. Physician-supervised eCRF data entry may have been susceptible to misinterpretation of instructions and incorrect patient classification by asthma severity. Indeed, our findings demonstrated that some patients classified as having mild asthma were prescribed medium- or high-dose ICS and long-term OCS. Furthermore, the prescription of SABA was used as an approximation of SABA use, but not all SABA prescriptions may have translated into actual use by patients; therefore, SABA use may have been overestimated (Citation24–26). Notably, a lack of continuity of care in the primary care setting in Thailand (Citation35) presented a challenge in attaining the pre-specified study inclusion criteria of ≥3 prior consultations with the same HCP. Additionally, only one patient aged 12–17 years was enrolled in this study, with all patients recruited from specialist care; therefore, the study population is not representative of the overall national patient population with asthma in Thailand and does not truly reflect the way asthma is currently being managed across the country. This selection bias may have contributed to the greater number of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma being recruited into the study, which precluded a comparison across asthma severities, and limited the generalizability of results. Moreover, the management of patients under specialist care likely contributed to optimal asthma management and thus improved clinical outcomes. Consequently, additional studies are required at the primary care level to gain a more comprehensive understanding of treatment practices and patient outcomes across Thailand. With increasing age a known risk factor for a concomitant diagnosis of asthma and COPD (Citation36,Citation37), and more than half of the study population aged ≥55 years, it is feasible that some patients with asthma and COPD-like symptoms may have been enrolled in this study, which could have impacted on treatment outcomes. Due to the small sample size, it was not feasible to examine the association between SABA prescriptions and asthma-related clinical outcomes. As such, it is not possible to categorically determine whether SABA overuse is predominantly linked to a small subset of patients with poorly controlled asthma, or indicative of a widespread health concern in Thailand. However, overall findings from SABINA III indicated that ≥3 SABA prescriptions/year (vs. 1–2 SABA prescriptions) were associated with increasingly lower odds of controlled or partly controlled asthma and higher rates of severe exacerbations across countries, healthcare settings, and asthma severities (Citation16). Finally, this study did not examine the impact of regional differences, such as urban and non-urban settings, on asthma prescription patterns or treatment outcomes; however, this should be an area of future research with larger patient numbers.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess SABA prescriptions in patients under specialist care in Thailand. Crucially, the real-world data generated from this study can support policymakers and clinicians in making pivotal changes in clinical practices to further improve the quality of care for all patients with asthma in Thailand. In the future, studies exploring potential factors contributing to SABA over-prescription and overuse, specifically with regard to disease management and medication adherence, will further enhance asthma management practices across Thailand.

Conclusions

Despite treatment under specialist care, almost 30% of patients were prescribed SABA in excess of the current treatment recommendations (≥3 SABA canisters in the previous 12 months). Approximately three-quarters of patients had well-controlled asthma, likely reflecting the fact that the prescription of maintenance medication generally conformed to internationally recommended treatment guidelines. Nevertheless, these findings highlight that SABA over-prescription remains widely prevalent in patients treated by specialists in Thailand, emphasizing the need for educational initiatives, policy changes to minimize SABA use, and enhanced adherence to the latest evidence-based recommendations to ensure further improvements in asthma management across the country.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data and provided input into the development of the manuscript, including preparation and critical feedback. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the manuscript for submission.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BMI | = | body mass index |

| eCRF | = | electronic case report form |

| GINA | = | Global Initiative for Asthma |

| ICS | = | inhaled corticosteroids |

| HCP | = | healthcare provider |

| LABA | = | long acting β2-agonist |

| LAMA | = | long-acting muscarinic antagonist |

| LTRA | = | leukotriene receptor antagonist |

| OCS | = | oral corticosteroids |

| OTC | = | over-the-counter |

| SABA | = | short-acting β2- agonist |

| SAMA | = | short-acting muscarinic antagonist |

| SABINA | = | SABA use IN Asthma |

| SD | = | standard deviation |

Acknowledgments

The medical writing support was provided by Nadine Rampf, PhD, of Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications, Mumbai, India) in accordance with the Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3) and funded by AstraZeneca.

Declaration of interest

NN reports receiving fees for advisory boards from Boehringer Ingelheim, and fees for providing independent medication education from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline. PS is an employee of AstraZeneca. MJHIB was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time the study was conducted and has shares in AstraZeneca. TT and AN have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Data underlying the findings described in this article may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Asthma Network (GAN). The global asthma report; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: http://globalasthmareport.org

- Boonsawat W, Thompson PJ, Zaeoui U, Samosorn C, Acar G, Faruqi R, Poonnoi P. Survey of asthma management in Thailand – the asthma insight and management study. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2015;33(1):14–20. doi:10.12932/AP0473.33.1.2015.

- Census and Economic Information Center. Thailand household income per capita; 2017 [cited 2021 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/thailand/annual-household-income-per-capita

- Dilokthornsakul P, Lee TA, Dhippayom T, Jeanpeerapong N, Chaiyakunapruk N. Comparison of health care utilization and costs for patients with asthma by severity and health insurance in Thailand. Value Health Reg Issues 2016;9:105–111. doi:10.1016/j.vhri.2016.03.001.

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: http://ginasthma.org

- O’Byrne PM, Jenkins C, Bateman ED. The paradoxes of asthma management: time for a new approach? Eur Respir J 2017;50(3):1701103. doi:10.1183/13993003.01103-2017.

- Aldridge RE, Hancox RJ, Robin Taylor D, Cowan JO, Winn MC, Frampton CM, Town GI. Effects of terbutaline and budesonide on sputum cells and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161(5):1459–1464. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9906052.

- Nwaru BI, Ekstrom M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J 2020;55(4):1901872. doi:10.1183/13993003.01872-2019.

- Bloom CI, Cabrera C, Arnetorp S, Coulton K, Nan C, van der Valk RJP, Quint JK. Asthma-related health outcomes associated with short-acting β2-agonist inhaler use: an observational UK study as part of the SABINA global program. Adv Ther 2020;37(10):4190–4208. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01444-5.

- FitzGerald JM, Tavakoli H, Lynd LD, Al Efraij K, Sadatsafavi M. The impact of inappropriate use of short acting beta agonists in asthma. Respir Med 2017;131:135–140. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.08.014.

- Stanford RH, Shah MB, D’Souza AO, Dhamane AD, Schatz M. Short-acting β-agonist use and its ability to predict future asthma-related outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;109(6):403–407. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.014.

- Shlomi D, Katz I, Segel MJ, Oberman B, Peled N. Determination of asthma control using administrative data regarding short-acting beta-agonist inhaler purchase. J Asthma 2018;55(5):571–577. doi:10.1080/02770903.2017.1348513.

- Shlomi D, Oberman B, Katz I. Short-acting bronchodilators purchase as a marker for asthma control. J Asthma 2022;59(1):206–212. doi:10.1080/02770903.2020.1837157.

- Thai Asthma Council and Association, The Asthma Association of Thailand. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of asthma in Thailand-adult revised edition-2020 [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.tac.or.th

- Cabrera CS, Nan C, Lindarck N, Beekman MJHI, Arnetorp S, van der Valk RJP. SABINA: global programme to evaluate prescriptions and clinical outcomes related to short-acting β2-agonist use in asthma. Eur Respir J 2020;55(2):1901858. doi:10.1183/13993003.01858-2019.

- Bateman ED, Price DB, Wang HC, Khattab A, Schonffeldt P, Catanzariti A, van der Valk RJP, Beekman MJHI. Short-acting β2-agonist prescriptions are associated with poor clinical outcomes of asthma: the multi-country, cross-sectional SABINA III study. Eur Respir J 2022;59(5):2101402. doi:10.1183/13993003.01402-2021.

- Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet L-P, Boushey HA, Busse WW, Casale TB, Chanez P, Enright PL, Gibson PG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180(1):59–99. doi:10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST.

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3.

- Khattab A, Madkour A, Ambaram A, Smith C, Muhwa CJ, Mecha JO, Alsayed M, Beekman MJHI. Over-prescription of short-acting β(2)-agonists is associated with poor asthma outcomes: results from the African cohort of the SABINA III study. Curr Med Res Opin 2022;38(11):1983–1995. doi:10.1080/03007995.2022.2100649.

- Alzaabi A, Al Busaidi N, Pradhan R, Shandy F, Ibrahim N, Ashtar M, et al. Over-prescription of short-acting β(2)-agonists and asthma management in the Gulf region: a multicountry observational study. Asthma Res Pract 2022;8(1):3.

- Shen S-Y, Chen C-W, Liu T-C, Wang C-Y, Chiu M-H, Chen Y-J, Lan C-C, Shieh J-M, Lin C-M, Wu S-H, et al. SABA prescriptions and asthma management practices in patients treated by specialists in Taiwan: results from the SABINA III study. J Formos Med Assoc 2022;121(12):2527–2537. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2022.05.014.

- Yorgancıoğlu A, Aksu K, Naycı SA, Ediger D, Mungan D, Gül U, Beekman MJHI, SABINA Turkey Study Group. Short-acting β(2)-agonist prescription patterns in patients with asthma in Turkey: results from SABINA III. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22(1):216. doi:10.1186/s12890-022-02008-9.

- Modi M, Mody K, Jhawar P, Sharma L, Padukudru Anand M, Gowda G, Mendiratta M, Kumar S, Nayar S, Manchanda M, et al. Short-acting β2-agonists over-prescription in patients with asthma: an Indian subset analysis of international SABINA III study. J Asthma 2023;60(7):1347–1358. doi:10.1080/02770903.2022.2147079.

- Suriyawongpaisal P, Aekplakorn W, Leerapan B, Lakha F, Srithamrongsawat S, von Bormann S. Assessing system-based trainings for primary care teams and quality-of-life of patients with multimorbidity in Thailand: patient and provider surveys. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20(1):85. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-0951-6.

- Tejativaddhana P, Briggs D, Fraser J, Minichiello V, Cruickshank M. Identifying challenges and barriers in the delivery of primary healthcare at the district level: a study in one Thai province. Int J Health Plan Manage 2013;28(1):16–34. doi:10.1002/hpm.2118.

- WHO Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS). Case study from Thailand; 2017 [cited 2023 Jan 10]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1344396/retrieve

- Thanaviratananich S, Cho SH, Ghoshal AG, Muttalif ARBA, Lin HC, Pothirat C, Chuaychoo B, Aeumjaturapat S, Bagga S, Faruqi R, et al. Burden of respiratory disease in Thailand: results from the APBORD observational study. Medicine 2016;95(28):e4090. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004090.

- Boonsawat W, Charoenphan P, Kiatboonsri S, Wongtim S, Viriyachaiyo V, Pothirat C, Thanomsieng N. Survey of asthma control in Thailand. Respirology 2004;9(3):373–378. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1843.2004.00584.x.

- Boonsawat W, Thepsuthammarat K. Reducing asthma admission: impact of the Easy Asthma Clinic Network. Eur Respir J 2012;40(56 Suppl):4342.

- Boonsawat W, Sawanyawisuth K. A real-world implementation of asthma clinic: make it easy for asthma with Easy Asthma Clinic. World Allergy Organ J 2022;15(10):100699. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100699.

- Aggarwal B, Shantakumar S, Hinds D, Mulgirigama A. Asia-Pacific Survey of Physicians on Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis (ASPAIR): physician beliefs and practices about diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of coexistent disease. J Asthma Allergy 2018;11:293–307. doi:10.2147/JAA.S180657.

- Wang E, Wechsler ME, Tran TN, Heaney LG, Jones RC, Menzies-Gow AN, Busby J, Jackson DJ, Pfeffer PE, Rhee CK, et al. Characterization of severe asthma worldwide: data from the international severe asthma registry. Chest 2020;157(4):790–804. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.053.

- Sobieraj DM, Weeda ER, Nguyen E, Coleman CI, White CM, Lazarus SC, Blake KV, Lang JE, Baker WL. Association of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonists as controller and quick relief therapy with exacerbations and symptom control in persistent asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2018;319(14):1485–1496. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.2769.

- Price D, Hancock K, Doan J, Taher SW, Muhwa CJ, Farouk H, Beekman MJHI. Short-acting β2-agonist prescription patterns for asthma management in the SABINA III primary care cohort. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2022;32(1):37. doi:10.1038/s41533-022-00295-7.

- Kitreerawutiwong N, Jordan S, Hughes D. Facility type and primary care performance in sub-district health promotion hospitals in northern Thailand. PLOS One 2017;12(3):e0174055. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174055.

- Soriano JB, Davis KJ, Coleman B, Visick G, Mannino D, Pride NB. The proportional Venn diagram of obstructive lung disease: two approximations from the United States and the United Kingdom. Chest 2003;124(2):474–481. doi:10.1378/chest.124.2.474.

- de Marco R, Pesce G, Marcon A, Accordini S, Antonicelli L, Bugiani M, Casali L, Ferrari M, Nicolini G, Panico MG, et al. The coexistence of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): prevalence and risk factors in young, middle-aged and elderly people from the general population. PLOS One 2013;8(5):e62985. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062985.