Abstract

Objective

Despite access to effective therapies many asthma patients still do not have well-controlled disease. This is possibly related to underuse of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and overuse of short-acting β2-agonists (SABA). Our aim was to investigate longitudinal trends and associated factors in asthma treatment.

Methods

Two separate cohorts of adults with physician-diagnosed asthma were randomly selected from 14 hospitals and 56 primary health centers in Sweden in 2005 (n = 1182) and 2015 (n = 1225). Information about symptoms, maintenance treatment, and use of rescue medication was collected by questionnaires. Associations between treatment and sex, age, smoking, education, body mass index (BMI), physical activity, allergic asthma, and symptom control were analyzed using Pearson’s chi2-test. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using logistic regression.

Results

Maintenance treatment with ICS together with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) and/or montelukast increased from 39.2% to 44.2% (p = 0.012). The use of ICS + LABA as-needed increased (11.1–18.9%, p < 0.001), while SABA use decreased (46.4– 41.8%, p = 0.023). Regular treatment with ICS did not change notably (54.2–57.2%, p = 0.14). Older age, former smoking, and poor symptom control were related to treatment with ICS + LABA/montelukast. In 2015, 22.7% reported daily use of SABA. A higher step of maintenance treatment, older age, obesity, shorter education, current smoking, allergic asthma, low or very high physical activity, and a history of exacerbations were associated with daily SABA use.

Conclusions

The use of ICS + LABA both for maintenance treatment and symptom relief has increased over time. Despite this, the problem of low use of ICS and high use of SABA remains.

Introduction

Despite access to effective therapies and continually updated treatment recommendations, many asthma patients still do not have well-controlled disease (Citation1–5). Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the cornerstone in the management of asthma (Citation1), but the proportion of asthma patients regularly treated with ICS remains low (Citation6). Since 2019, ICS + formoterol is recommended as a first-line therapy for asthma according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) (Citation1). Formoterol is a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) with rapid action, similar to short-acting β2-agonists (SABA), and is therefore, suitable as rescue medication (Citation7). For mild asthma and with symptoms occurring less than twice a week, SABA used to be recommended as monotherapy for as-needed symptom relief (Citation1).

SABA-treatment results in rapid reduction of asthma symptoms making it more appealing to patients when asthma is worse, rather than increasing the dose of ICS. This may lead to an insufficient treatment of the underlying inflammation (Citation8). Overuse of SABA has been related to an increased risk of asthma exacerbations and mortality, and the risk of mortality was seen to be further increased with higher use of SABA (Citation9). A previous Swedish study found that from 2001 to 2005, there was increased use of ICS in combination with either LABA or montelukast, or the combination of all three (Citation2). There was no difference over time in prevalence of SABA as monotherapy.

In this study, we aimed to address the change in asthma treatment from 2005 to 2015 among a population from both primary and secondary care in Sweden and to identify factors related to the use of SABA and maintenance treatment with ICS in combination with either LABA and/or montelukast.

Methods

Population

This research used the Swedish PRAXIS study, involving adults with asthma in seven regions in central Sweden first included in 2005 (Citation2,Citation10,Citation11). From each region, the pulmonary medicine unit at the central hospital, the internal medicine unit at a randomly selected district hospital and eight randomly selected primary health centers (PHCs) were invited to participate: in total 14 hospitals and 56 PHCs. PHCs with less than 3000 listed patients were excluded.

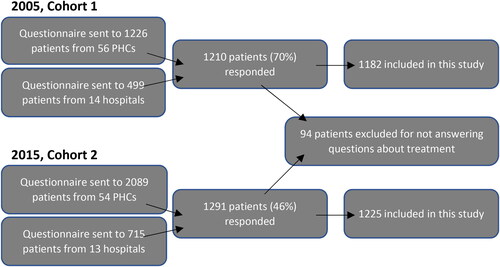

A questionnaire was sent to randomly selected patients with physician-diagnosed asthma (ICD-10 code J45) that had attended the clinic during 2000–2003. Patients that had not answered the questions about their medication were excluded from this study. A second cohort was created in 2015, with randomly selected patients from 13 hospitals and 54 of the original 56 PHCs. See flow chart for details on inclusion of patients (). To identify factors related to differences in treatment, we used data from 2015.

Questionnaires

Data on patient characteristics including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), education (dichotomized into shorter and longer duration), smoking history, and physical activity were extracted from the patient questionnaire. Age was divided into four groups (≤39, 40─54, 55─64, ≥65 years) in all analyses except for the interaction analyses, where age was dichotomized into <55 and ≥55 years. Longer duration of education was defined as at least 3 years longer than Swedish compulsory school for 9 years. Smoking was divided into three groups: never, former, or current (daily or occasional use). If patients experienced asthma symptoms or allergic symptoms from the eyes or nose in contact with pollen or furry animals, it was defined as allergic asthma.

Based on the answers to questions about pharmacological treatment, we divided maintenance treatment into four steps; 1a, no regular or periodic treatment with ICS; 1b, periodic but not regular treatment with ICS; 2, regular treatment with ICS only; 3, regular treatment with ICS in combination with either LABA and/or montelukast. The questionnaire also provided information about use of rescue medication more than twice during the previous week in order to reduce asthma symptoms, with separate questions for SABA, LABA, and combined ICS + LABA. The patients were also asked in the questionnaire about number of courses of oral corticosteroids (OCS) due to an asthma exacerbation during the past 6 months, and whether they were using OCS regularly, regardless of indication.

Exacerbation during the past 6 months was defined as either being prescribed OCS or having had an emergency visit to the hospital or primary health center due to worsening of asthma.

In 2015, the questionnaire included the Asthma Control Test (ACT) (Citation12), which was used to assess symptom control. Well-controlled asthma was defined as an ACT score of ≥20 and poorly controlled asthma as <20.

Based on the fourth question in ACT, about use of SABA as rescue medication, we derived a variable for those who responded that they used rescue medication daily (alternative 1 or 2 in ACT). This question is translated from Swedish to “During the past 4 wk, how often have you used your short-acting bronchodilator (such as Bricanyl, Ventoline, Airomir)?”. To ensure that the group responding daily SABA use actually used SABA and not any other kind of rescue medication, we further examined whether they had taken extra doses of SABA more than twice during the previous week. Only patients reporting both daily SABA use in ACT and extra doses of SABA more than twice during the previous week to reduce asthma symptoms were defined as using SABA daily. Data on daily SABA use are only available from 2015.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Nominal variables were compared with Pearson’s chi2-test. Continuous variables were compared using the two-sample t-test. Multiple logistic regression adjusted for confounding factors was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Dependent variables were maintenance treatment on step 3, compared to treatment on any other step, and daily SABA use. Interactions were assessed for sex or age with smoking, education, BMI, allergic asthma and physical activity, in relation to the risk of maintenance treatment on step 3 or daily use of SABA. A p value of <0.05 or 95% CIs not including 1.00 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Uppsala Regional Ethical Review Board (2004: M-445 and 2011/318). All participants have given written consent for their participation.

Results

Comparison of 2005 and 2015

The characteristics of participants are presented in . The 2015 cohort members were slightly older than the 2005 cohort (mean age 54.0 vs. 49.9, p < 0.001), had significantly higher BMI, were less likely to be current smokers and more likely to have had longer education.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants in 2005 and 2015 (n (%)).

Treatment with ICS in combination with LABA and/or montelukast increased between 2005 and 2015. Regular treatment with OCS (regardless of indication) also increased significantly in this time. There was no significant difference in regular treatment with montelukast, regardless of inhalation treatment. Neither was there any difference in oral courses of corticosteroids due to asthma exacerbations in the past 6 months. The overall use of bronchodilator for symptom relief more than twice during the previous week did not change between 2005 and 2015, but the use of SABA and LABA decreased, and the use of a combination of ICS + LABA as-needed increased. ().

Table 2. Pharmacological asthma treatment in 2005 compared to 2015 (n (%)).

Results from 2015

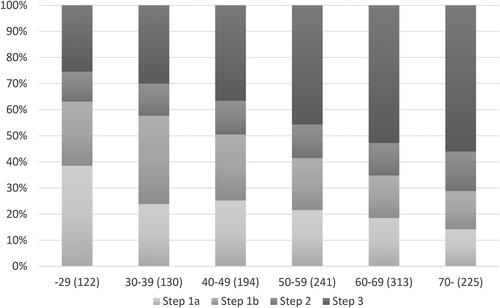

Patients with poor symptom control (ACT < 20) were found on all treatment steps, with the highest proportion of patients with poor symptom control on step 3 and the lowest on step 1a (). The same trend was found for exacerbations where the prevalence of exacerbations was 8% in step 1a and 36% in step 3 (). Overall, 41.4% had a poor symptom control in 2015. Older age, poor symptom control, and former smoking were statistically significantly related to higher level of maintenance treatment. The distribution of treatment steps 1─3 in different ages is displayed in , showing an increase in the proportion on treatment step 3 with increasing age. In the initial analyses, allergic asthma was related to a higher risk of having maintenance treatment with ICS, and shorter education was related to maintenance treatment on step 3, but there were no differences in treatment on step 3 for either of these factors when adjusted for potential confounding factors. There were no differences in maintenance treatment associated with sex, physical activity, or BMI.

Figure 2. Prevalence (%) of treatment on step 1–3 within each age group (years (n)) in 2015.

Step 1a: No maintenance treatment. Step 1b: Periodic treatment with inhaled corticosteroids.

Step 2: Regular treatment with inhaled corticosteroids only. Step 3: Regular treatment with inhaled corticosteroids in combination with LABA and/or montelukast.

Table 3. Asthma treatment 2015 in patients on different treatment steps.

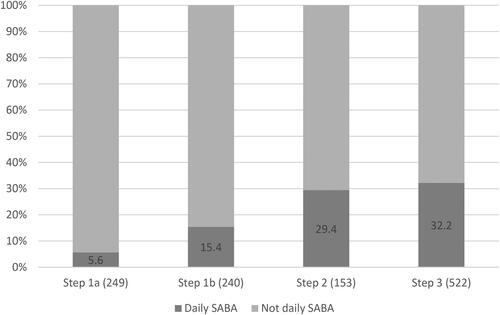

Daily use of SABA was reported by 264 patients (22.7%) in 2015. Patients with higher level of maintenance treatment were more likely to take SABA daily (). Older age, obesity, shorter education, current smoking, allergic asthma, lower as well as higher physical activity and a history of exacerbations were independently associated with daily SABA use ().

Figure 3. Prevalence (%) of daily use of SABA within each treatment step (n) in 2015.

Step 1a: No maintenance treatment. Step 1b: Periodic treatment with inhaled corticosteroids.

Step 2: Regular treatment with inhaled corticosteroids only. Step 3: Regular treatment with inhaled corticosteroids in combination with LABA and/or montelukast.

Table 4. Daily SABA use in 2015 (n (%), p value within group for chi2 test) and adjusted odds ratio (OR (95% CI))*.

No interactions were found for sex or age with smoking, education, BMI, allergic asthma, or physical activity, in relation to the risk of maintenance treatment on step 3 or daily use of SABA.

Discussion

In this longitudinal observational study in Sweden, we found that the use of ICS + LABA increased both as maintenance treatment and as rescue medication from 2005 to 2015. In GINA, since 2019 ICS + formoterol is recommended as an optimal first-line therapy in western countries (Citation1). This shift from SABA to ICS + formoterol in step 1 is not yet fully implemented in Swedish national or local guidelines. However, the overall use of regular ICS did not increase during the study period. Our results, with only just over half of asthma patients using ICS regularly in both cohorts is consistent with other reports of underuse of ICS (Citation6,Citation13). Another 20% of patients in our study used ICS periodically, which did not differ over time.

We speculate that the low use of ICS may, to some extent, be due to low adherence, as studies have found the adherence to ICS to be suboptimal, ranging from 22% to 63% (Citation14). In a previous study, asthma patients were asked about their understanding of the role of asthma medication and their concerns about ICS, and there were indications of confusion between the role of ICS and bronchodilators (Citation15). Approximately half of the patients were very or somewhat concerned about using ICS. Common concerns about ICS were fear of side effects and the misconception that ICS could become less effective when used on a long-term basis. Adherence and concerns about medication have not been monitored in this study.

As many as 41% of asthma patients reported poor symptom control with an ACT score below 20. Even on step 1a, which consisted of participants with no maintenance treatment, as many as 18% had poor symptom control. This is in line with previous findings showing that many asthma patients do not have well-controlled asthma (Citation5,Citation16,Citation17).

Our finding of an overall high use of daily SABA is alarming since higher use of SABA is related to more frequent exacerbations and higher mortality (Citation9). High SABA use has also been reported previously from countries across Europe (Citation18). Use of ICS + LABA as needed is associated with a reduced risk of exacerbations both for the short and long-term, compared with SABA as needed in mild asthma (Citation19,Citation20). Most patients reporting daily use of SABA in our study have maintenance treatment on step 3, possibly indicating that their asthma is difficult to treat, but even on step 1 (1a + 1b), with no regular ICS-treatment, 10% of the patients reported daily use of SABA. Since our data on use of medicines is based on self-report, we cannot know if the patients with high use of SABA have difficulty treating their asthma or if they use the medicines incorrectly. We also do not know whether lack of maintenance treatment is due to lack of compliance or due to under-prescription.

The high use of SABA in the group with maintenance treatment on step 3 raises questions about inhaler techniques, which we have not monitored in this study. Incorrect inhaler technique has been associated with poor asthma control (Citation21,Citation22). In previous studies, only about 30% of patients has been observed using a correct technique and 30% using a poor technique, and unfortunately the prevalence of poor technique has not improved over 40 years (Citation23). Some studies indicate that older age, shorter education, and comorbidities such as obesity, may be associated with a higher proportion using inhalers inappropriately (Citation21), but there are conflicting results for age. As seen in our study, these factors were also associated with daily SABA use.

Older age was associated with greater use of maintenance treatment on the highest steps, and the oldest patients (≥65) also had a higher likelihood of daily SABA use compared with the younger age groups. Older age has been associated with regular use of ICS-treatment and fewer interruptions in treatment in other studies (Citation13,Citation24).

There was no association between treatment steps and BMI, but obesity was related to a higher risk of daily SABA use. In previous studies, obesity was associated with a higher risk of development of asthma and poorer asthma control (Citation4,Citation25). In our study obesity was related to daily SABA use, indicating a higher symptom burden. Patients with obesity appears to have a decreased response to ICS, and may require longer treatment exposure to gain effect (Citation26,Citation27). Obesity also imposes direct mechanical effects on respiration, with increased respiratory effort due to increased intra-abdominal pressure and lower lung volume (Citation25), and these patients may benefit from non-pharmacological interventions such as weight loss to reduce symptoms (Citation28).

In our study, former smoking was related to a higher risk of maintenance treatment on step 3. Current smoking on the other hand was related to more frequent daily SABA use. Smoking is associated with resistance to ICS, which can decrease the effect of the medication (Citation29). In a previous study, nonsmoking was related to a higher probability of having anti-asthmatic medication compared with current smokers, while former smokers were equally likely to have anti-asthma medication as nonsmokers (Citation30). In a follow up of that study, however, the difference in smoking history was not statistically significant after adjustment for sex, age, BMI, asthma exacerbations, doctor visits, survey, and country (Citation6). In our study, there were no difference between never smokers and current smokers for maintenance treatment on step 3.

The prevalence of patients with regular OCS use increased from 3% to 5% from 2005 to 2015. This prevalence is higher than has been found in other Swedish studies (Citation31,Citation32). The probable reason for this discrepancy is that in this study we do not know the indication for the treatment, whereas in the previous studies only OCS used for asthma treatment was assessed.

There were statistically significant differences between the 2005 and 2015 cohorts for age, smoking, education and BMI. Shorter education was more common in the older generations in Sweden. During the 10 years from 2005 to 2015 the profile of the Swedish population has changed, and is probably reflected in our sample. The decrease in smoking and increased average BMI may also be due to general trends (Citation33,Citation34).

The main strength of our study is that it is conducted in a real-world setting, with questions asking how the patients take their medicine rather than how it is prescribed, hopefully reflecting the reality of asthma patients. Self-reported data may on the other hand add uncertainty of the accuracy of the data due to recall and other reporting biases. In this study, asthma was defined as having doctor-diagnosed asthma, retrieved from the medical records and identified using the ICD-10 code. Doctor-diagnosis of asthma was based on GINA guidelines at the time. There is a risk that patients have been misdiagnosed and incorrectly included in this study. Although some patients may have been included in the study without having asthma according to GINA guidelines, we believe it is unlikely that this has had any major impact on the conclusions. A limitation to the study is that we lack information on comorbidities and cannot therefore know if some of the patients apart from asthma also had other respiratory diseases.

In the questionnaires, there were combined questions for any kind of LABA concerning both maintenance treatment and extra doses. Therefore, we cannot differentiate between formoterol and other kinds of LABA, which would have been of interest since the current guidelines recommend use of formoterol over other LABAs. When this study was conducted these recommendations did not yet apply.

In this study, asthma control was assessed using ACT and self-reported history of exacerbations. A limitation is that we had no data on objective measurements of asthma control such as bronchodilatory responsiveness or FeNO. The majority of the patients included in this study were from primary care. At Swedish primary health care centers, the access to spirometry does not allow for continuous tests during follow up of patients with diagnosed asthma and FeNO is not yet accessible in most Swedish primary health care centers. In clinical praxis asthma control is, therefore, usually assessed using the ACT.

Conclusions

The most important finding in our study is that the use of ICS/LABA both for maintenance treatment and symptom relief has increased over time. Despite this, the problem of low use of ICS and high use of SABA remains. Our results show that there are asthma patients with high use of SABA and no ICS-treatment. Hopefully these patients will benefit from the new guidelines and start treatment with ICS. In a future study, we plan to follow this group to see how the treatment has changed after the new guidelines are introduced.

Disclosure statement

Caroline Ahlroth Pind, Marta A Kisiel, Anna Nager and Mikael Hasselgren has no conflicts of interests to declare. Björn Ställberg has received honoraria for educational activities and lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Meda, Novartis and Teva, and has served on advisory boards arranged by AstraZeneca, Novartis, Meda, GlaxoSmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim outside the submitted work. Karin Lisspers has received honoraria for educational activities from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca and Chiesi and served on advisory boards held by GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. Josefin Sundh has received honoraria for educational activities and lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi and Novartis outside the submitted work. Hanna Sandelowsky has received honoraria for educational activities from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, and TEVA, and has served on advisory boards arranged by AstraZeneca, Novartis, Chiesi, and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. Scott Montgomery has received research grants and/or honoraria for advisory boards/lectures from Roche, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Teva, Merck and IQVIA outside the submitted work. Christer Janson has received honoraria for educational activities and lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Orion, Novartis and Sanofi outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- 2021 GINA Main Report [Internet]. Global initiative for a-GINA. 2021. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/ [cited 11 November 2021].

- Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Hasselgren M, Janson C, Johansson G, Svärdsudd K. Asthma control in primary care in Sweden: a comparison between 2001 and 2005. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(4):279–286. doi:10.4104/pcrj.2009.00024.

- Backer V, Bornemann M, Knudsen D, Ommen H. Scheduled asthma management in general practice generally improve asthma control in those who attend. Respir Med. 2012;106(5):635–641. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.005.

- Tuomisto LE, Ilmarinen P, Niemelä O, Haanpää J, Kankaanranta T, Kankaanranta H. A 12-year prognosis of adult-onset asthma: seinäjoki Adult Asthma Study. Respir Med. 2016;117:223–229. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.017.

- Cazzoletti L, Marcon A, Janson C, Corsico A, Jarvis D, Pin I, Accordini S, Almar E, Bugiani M, Carolei A, et al. Asthma control in Europe: a real-world evaluation based on an international population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1360–1367. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.019.

- Janson C, Accordini S, Cazzoletti L, Cerveri I, Chanoine S, Corsico A, Ferreira DS, Garcia-Aymerich J, Gislason D, Nielsen R, et al. Pharmacological treatment of asthma in a cohort of adults during a 20-year period: results from the European Community Respiratory Health Survey I, II and III. ERJ Open Res. 2019;5(1):00073–2018. doi:10.1183/23120541.00073-2018.

- Seberová E, Andersson A. Oxis®(formoterol given by Turbuhaler®) showed as rapid an onset of action as salbutamol given by a pMDI. Respir Med. 2000;94(6):607–611. doi:10.1053/rmed.2000.0788.

- O’Byrne PM, Jenkins C, Bateman ED. The paradoxes of asthma management: time for a new approach? Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1701103. doi:10.1183/13993003.01103-2017.

- Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(4):1901872. doi:10.1183/13993003.01872-2019.

- Sundh J, Wireklint P, Hasselgren M, Montgomery S, Ställberg B, Lisspers K, Janson C. Health-related quality of life in asthma patients - A comparison of two cohorts from 2005 and 2015. Respir Med. 2017;132:154–160. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.10.010.

- Kämpe M, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, Sundh J, Montgomery S, Janson C. Determinants of uncontrolled asthma in a Swedish asthma population: cross-sectional observational study. Eur Clin Respir J. 2014;1(1):24109. doi:10.3402/ecrj.v1.24109.

- Asthma Control Test [Internet]. Asthma control test. 2021. Available from: https://www.asthmacontroltest.com/ [cited 11 November 2021].

- Ekström M, Nwaru BI, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Risk of rehospitalization and death in patients hospitalized due to asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(5):1960–1968.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.030.

- Bårnes CB, Ulrik CS. Asthma and adherence to inhaled corticosteroids: current status and future perspectives. Respir Care. 2015;60(3):455–468. doi:10.4187/respcare.03200.

- Boulet LP. Perception of the role and potential side effects of inhaled corticosteroids among asthmatic patients. Chest. 1998;113(3):587–592. doi:10.1378/chest.113.3.587.

- Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24(1):14009. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9.

- Demoly P, Annunziata K, Gubba E, Adamek L. Repeated cross-sectional survey of patient-reported asthma control in Europe in the past 5 years. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21(123):66–74. doi:10.1183/09059180.00008111.

- Janson C, Menzies-Gow A, Nan C, Nuevo J, Papi A, Quint JK, Quirce S, Vogelmeier CF. SABINA: an overview of short-acting β2-agonist use in asthma in European countries. Adv Ther. 2020;37(3):1124–1135. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01233-0.

- O’Byrne PM, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, Barnes PJ, Zheng J, Gustafson P, Lamarca R, Puu M, Keen C, Alagappan VKT, et al. Effect of a single day of increased as-needed budesonide–formoterol use on short-term risk of severe exacerbations in patients with mild asthma: a post-hoc analysis of the SYGMA 1 study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(2):149–158. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30416-1.

- Beasley R, Holliday M, Reddel HK, Braithwaite I, Ebmeier S, Hancox RJ, Harrison T, Houghton C, Oldfield K, Papi A, et al. Controlled trial of budesonide–formoterol as needed for mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):2020–2030. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1901963.

- Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, Dunlop WCN, Heron L, Farrington E, Dekhuijzen R. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y.

- Price DB, Román-Rodríguez M, McQueen RB, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Carter V, Gruffydd-Jones K, Haughney J, Henrichsen S, Hutton C, Infantino A, et al. Inhaler errors in the CRITIKAL study: type, frequency, and association with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(4):1071–1081.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.01.004.

- Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S. Systematic review of ein inhaler use: has patient technique improved over time? Chest. 2016;150(2):394–406. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.041.

- Laforest L, El Hasnaoui A, Pribil C, Ritleng C, Osman LM, Schwalm M-S, Le Jeunne P, Van Ganse E. Asthma patients’ self-reported behaviours toward inhaled corticosteroids. Respir Med. 2009;103(9):1366–1375. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.010.

- Ricketts HC, Cowan DC. Asthma, obesity and targeted interventions: an update. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;19(1):68–74. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000494.

- Peters-Golden M, Swern A, Bird SS, Hustad CM, Grant E, Edelman JM. Influence of body mass index on the response to asthma controller agents. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(3):495–503. doi:10.1183/09031936.06.00077205.

- Camargo CA, Boulet L-P, Sutherland ER, Busse WW, Yancey SW, Emmett AH, Ortega HG, Ferro TJ. Body mass index and response to asthma therapy: fluticasone propionate/salmeterol versus montelukast. J Asthma. 2010;47(1):76–82. doi:10.3109/02770900903338494.

- Mohan A, Grace J, Wang BR, Lugogo N. The effects of obesity in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019;19(10):49. doi:10.1007/s11882-019-0877-z.

- Stapleton M, Howard-Thompson A, George C, Hoover RM, Self TH. Smoking and asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(3):313–322. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100180.

- Janson C, Chinn S, Jarvis D, Burney P. Individual use of antiasthmatic drugs in the European community respiratory health survey. Eur Respir J. 1998;12(3):557–563. doi:10.1183/09031936.98.12030557.

- Janson C, Lisspers K, Ställberg B, Johansson G, Telg G, Thuresson M, Nordahl Christensen H, Larsson K. Health care resource utilization and cost for asthma patients regularly treated with oral corticosteroids – a Swedish observational cohort study (PACEHR). Respir Res. 2018;19(1):168. doi:10.1186/s12931-018-0855-3.

- Ekström M, Nwaru BI, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Oral corticosteroid use, morbidity and mortality in asthma: a nationwide prospective cohort study in Sweden. Allergy. 2019;74(11):2181–2190. doi:10.1111/all.13874.

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Tobaksrökning, daglig [Internet]. Stockholm: Folkhälsomyndigheten; 2022. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/fu-tobaksrokning [cited 28 October 2022].

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. Övervikt och fetma [Internet]. Stockholm: Folkhälsomyndigheten; 2022. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/fu-overvikt-och-fetma [cited 28 October 2022].