Abstract

Since 2006, the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management is a policy framework to promote chemical safety around the world. In 2009, safety of nanomaterials has been recognised as an Emerging Policy Issue, and awareness to it has improved in the last two decades. Various countries act as pioneers in their respective geographic regions. This article presents the Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan of Thailand and its implementation since 2012, when on the third International Conference on Chemicals Management nanosafety was amended as emerging policy issue. In 2015, an intersessional process was started to negotiate a new post-2020 regime. This process was delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic, so many countries have not yet implemented nanosafety in their national legislations. Therefore, it is important to keep nanosafety in the post-2020 context of the Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management as an issue of concern without going a second time through an elaborate evaluation process again.

1. Introduction

Global chemicals policy has been quite successful since half a century. Several multilateral environmental agreements such as the Montreal Protocol for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, the Basel Convention on Hazardous Wastes, and the Rotterdam, Stockholm, and Minamata Conventions have been negotiated and ratified. The Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) is like an umbrella above these conventions. SAICM's overall objective was to achieve sound management of chemicals throughout their life cycle so that by the year 2020 chemicals are produced and used in ways that significantly minimize adverse impacts on the environment and human health (SAICM Citation2006a). In addition, the international community has discussed emerging policy issues on several fora. The safety of manufactured nanomaterials is such an emerging policy issue.

Thailand early recognised the opportunities and risks associated with the use of nanomaterials and created appropriate structures to exploit the opportunities of nanomaterials while increasing the safety in their handling, for this purpose developing and implementing a Nanosafety Strategic and Ethics Plan. In this article this plan is explained and the importance of global cooperation in enhancing nanosafety is addressed. SAICM has proven to be an ideal platform for global discussion of nanosafety as an emerging policy issue. With this article is also proposed that global nanosafety should be further developed as an issue of concern in the post 2020 context.

2. The nanosafety and ethics strategic plan of Thailand

2.1. Coordination between ministries and other stakeholders

In Thailand, the first Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan was started for the years 2012–2016, and so far the second plan has been developed which covered the period of 2017–2021 (see NANOTEC Citation2017). Since Nanosafety issues are still a matter of concern for policy makers, therefore in Thailand we think it may be a good idea to incorporate this issue together with the guideline for ethical impact assessment for nanomaterials and products containing nanomaterials for implementation at the same level. During these years, the number of commercial products increased and many of them involved nanomaterials for added value products. Therefore, the following three government organizations started a strategic nano partnership:

the Thai Food and Drug Administration (FDA) responsible for controlling nano products for health, i.e. food, drugs, medical devices, cosmetics, and household sanitary products,

the Thai Industrial Standards Institute (TISI) responsible for the standard of industrial products, and

the National Nanotechnology Center (NANOTEC) responsible in research and development, innovation and engineering, and application of nanotechnology in product prototypes and their transfer to industry through technology license agreements.

These agencies agreed to collaborate and monitor that nanotechnology is applied to improve the value of products, at the same time not overlooking risks and dangers which may arise. In addition, other agencies namely the Department of Disease Control, the Department of Health, the Department of Medical Services who are under the Ministry of Public Health, the Department of Industrial Works under the Ministry of Industry, and the Nanotechnology Association of Thailand, an independent entity, are also in agreement that Thailand shall manage to promote the Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan. This strategic plan shall be implemented as a guideline for creating operational action plans by relevant agencies including reviewing and updating the action plan annually in order to provide updates, monitoring, and flexibility to achieve their goals.

The core organization is the National Science Technology and Innovation (STI) Policy Office which was established in 2008 as an autonomous public agency to implement the policy set forth by the National Council of Research and Innovation Policy. The two Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plans were approved by the Thai Cabinet in 2012 and 2018 through the lead of STI Policy Office with strong collaborations among the mentioned agencies above. NANOTEC has worked closely with STI to appoint the committees to create the strategies and policy in order to promote understanding, overseeing, monitoring, and managing the safety and ethics related to nanotechnology. In addition, NANOTEC controls the nanoproducts in Thailand. The current nanosafety strategic plan has been extended now to 2024 as approved by Office of the National Higher Education Science Research and Innovation Policy Council (NXPO) (NANOTEC Citation2021).

2.2. Vision, objectives, and key performance indicators of the strategic plan

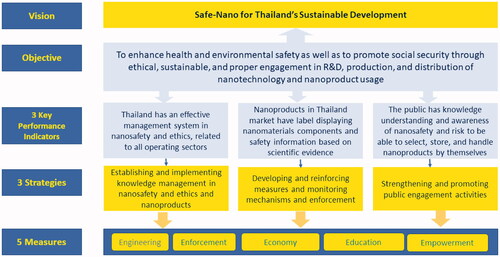

A diagram on the relationship between vision, objectives, indicators, strategies, and measures of the National Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan (2017–2021) is shown in .

Figure 1. Relationships between vision, objective, indicators, strategies, and measures of the National Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan (2017–2021).

The vision Safe-nano for Thailand’s sustainable development promotes social development in many aspects of health, education, environment, and economy.

The objective is to enhance public health and environmental safety, as well as to promote social security through ethical, sustainable, and proper support of research and development, production, distribution, and usage of nanoproducts.

Key performance indicators and targets for the Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan (2017–2021) are the following:

An effective management system of nanosafety and ethics is related to all operating sectors.

Marketed nanoproducts are labelled displaying nanomaterial components and safety information based on scientific evidence.

The public has sufficient knowledge and understanding to be aware of safety and risks associated with storage and handling of nanoproducts

To achieve the vision and objectives of the plan, three strategies have been determined to involve and integrate all sectors.

Strategy 1: Establish and implement knowledge management in safety and ethics of nanoproducts;

Strategy 2: Develop and reinforce measures of monitoring and enforcement mechanisms;

Strategy 3: Strengthen and promote public engagement.

Measures: These strategies are developed from Thailand’s Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, and Threat analysis for nanosafety and ethics, covering five working fields:

Engineering

Enforcement

Economy and finance

Education and knowledge management

Empowerment.

Implementation of the strategic plan is a significant process, it requires synergy, teamwork, proper technology, and vivid target. It unifies the objective with strategies as following:

Operation by focusing on every sector’s engagement: set clear goals and share responsibilities in order to enhance efficiency. Moreover, establish in mechanisms where beneficiaries and affected parties are involved in analysing, planning and making decisions in every process.

Reinforce knowledge and understanding to the public: the strategic plan emphasizes that each sector needs to establish work plans, projects and activity plans, which conform to the national policy and strategy. Nanosafety development shall be a national policy to be able to communicate to the public and related parties on how to manage and develop the strategic plan. Enhance understanding of nanosafety as well as create engagement in the monitoring process. Rise awareness on the potential risks and unexpected outcomes that may occur within the community and society.

Adapt work plans, projects, and activity plans to fit budget approval practice: each sector must concern in the work plans, projects and activity plans the time frame of the strategic plan as well as the vision, policy, public needs and the country’s development situation.

Public engagement: in order to make the policy and operation of the strategic plan to be fully effective, the public engagement shall be included in the private sector on nanosafety management. Several measures shall be included (1) strengthen communities’ awareness and monitoring of nanomaterials manufacturing process, (2) promote learning on the advantages of nanomaterials and nanosafety, (3) increase coordination in the community and different sectors aiming to produce concrete operational outcomes.

The mechanism of the nanosafety and risk management committee is used to improve the implementation: this process involves NANOTEC, representatives of the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Labour, the Ministry of Industry, the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, and of related parties from both public and private sectors. This brings integration, results in collaboration, and leads to financial support for operations concerning the nanosafety and risk management.

2.2.1. Implementing the strategic plan

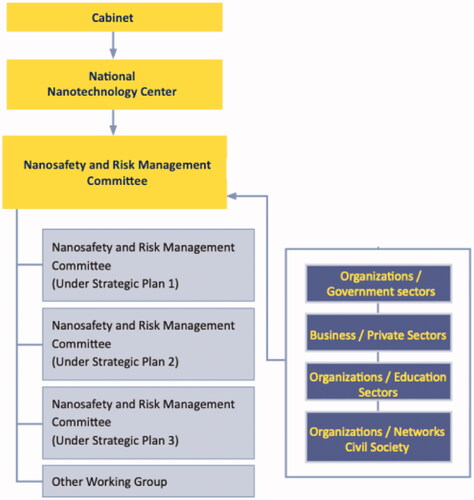

The organization structure with clear roles and missions of each sector leads to the implementation starting from the cabinet level to the operating level (). Several ministries and sectors are integrated in order to determine a strategy which involves nanosafety operations and the national financial plans such as determining the primary responsible agencies to work as a coordinator for the implementation plan, in order to emphasize engagement of ministries and network sectors. The budget submitting process of ministries and different sectors needs to include an annual implementation plan, which conforms to each sector’s roles and missions. The nanosafety and risk management committee coordinates, pushes forward and promotes financial support whereas different sectors work together.

2.3. Monitoring and evaluation

The process of monitoring and evaluation must follow the framework of public administration in a result-oriented approach. The concept includes the evaluation of key success indicators in different dimensions. A monitoring and evaluating committee is designated with representatives from government sectors, research centers, education sectors, and private sectors. They continuously evaluate and compile past performance at least once a year. The results will then be used by the Nanosafety and Risk Management Committee to efficiently follow up and speed up the implementation plan.

2.3.1. Status and trends of nanotechnology research and products in Thailand

The Thai government has also approved the National Nanotechnology Policy Framework (2012–2021) which provides national guidelines for nanotechnology development. It calls for a dramatic increase of science, technology, and innovation in nanotechnology. The guidelines cover nano safety practices for industrial sectors, safety practice guidelines for nanomaterials, practices for nano-healthcare products for entrepreneurs, and nano safety guidelines. The momentum continued in the area of building public awareness of direct and indirect effects of nano materials and nano products to health and environment. At present status, the Nanosafety Strategic and Ethics Plan has been officially extended into 2024, as per approval by the NXPO in December 2020 (NANOTEC Citation2021).

Successful case studies of companies active in nanoparticle technology reflect the Thai nanotech market. The first example is a Thai petrochemical company which started operation in 2014. One of their products is an antibacterial agent which can be supplied in almost any type of carrier including Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) copolymers in powder form with antibacterial effect up to 99% under the JIS Z2801 standard, which can be used for plastic products, sanitary ware, fibres, rubber, paints, and agriculture. The plant produces nanoparticles with production capacity of 140 tons per year and had net revenue of about 40,000 million Baht (1.25 Billion USD) announced by the company CEO in February 2021.

The second example is a nanotechnology-based company specializing in nanomaterial synthesis and applications. As spin-off of a research unit at the faculty of science of Chulalongkorn University, the company’s focus is on silver and gold nanoparticles. Other nanoparticles made of TiO2, SiO2, or Al2O3 are also available.

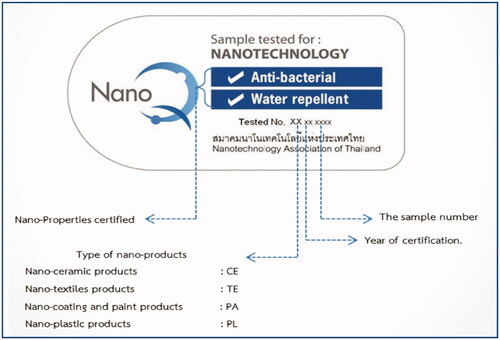

Since 2010 NanoQ exists, a voluntary label () for industrial products containing nanomaterials. NanoQ is issued by the Nanotechnology Association of Thailand, an independent association to support and promote awareness of nanotechnology innovations. It helps to build consumers’ confidence and sets quality standards. Companies wishing to obtain the label for a certain product can apply at the Association which, together with NANOTEC, will have the product tested by dynamic light scattering and certified of having particles of nano sizes and also for any other activity and efficacy claimed.

A yearly auditing process will also be part of the NanoQ mark package. Certification mark plays an important role in the commercial sector. It acts as evidence of the existence of follow-up agreements between manufacturers and national accredited testing and certification organization. With the increase of new nano-enabled products on the market, NanoQ certification will be an important factor to encouraging domestic manufacturers to develop nano products and promote consumers' acceptance. To date, 7 NanoQ labels have been awarded, with several more waiting in the pipeline.

In addition, the strategic plan has also been instrumental in initiating various activities such as creation of the Nanosafety Network for Industry and setting up of a Standards Development Organization which is approved and certified by TISI. At present, it is a function of the TISI and since 2020 they collaborate with NANOTEC to issue the standards for herbal extract nano-encapsulation particles, such as black ginger, turmeric, and centella extracts for beverage and cosmeceutical industries. Currently, the working group is pushing to complete draft industrial standards for a herb extract (Kaempferia extract) to be submitted to TISI for final approval within 2021.

NANOTEC has established an easy to read mobile phone application (in Thai language) of the existing seven industrial standards that have been approved by TISI, to promote nanosafety and industrial standards awareness among local industries.

On 9th December 2020, a collaborative partnership agreement between the Department of Industrial Works, the Consumer Protection Board, the Council of Scientific and Technological Associations, the Federation of Thai Industry, the Thai FDA, the National Institute of Metrology (NIMT), the Nanotechnology Association of Thailand (NAT), the TISI, and NANOTEC was established. The aim of this partnership is to promote the Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan 2017–2024, in order to enhance industrial understanding and awareness of how new nano-enabled products can pose risks to human and environmental health. In addition to existing industrial standards related to nanotechnology, the network will also explore other activities such as the generation of an industrial data base, of easy-to-read safety publications and manuals, or the participation in seminars and exhibitions.

2.4. Nanosafety research at NANOTEC

Research projects included nanoparticle-coated fabrics, which were subject to wash-water contamination tests. Nano-titanium dioxide (TiO2) coated fish tanks were tested for toxicity to fish. Skin creams containing titanium dioxide nanoparticles were also tested for skin penetration through a model (pig) skin. Ecotoxicity of nanosilver in waste water was also tested. More comprehensive nanomaterial safety data were generated in the Nano Safety and Risk Assessment Laboratory of NANOTEC, which specifically addresses two main areas regarding safety investigation of nanomaterials: Human health and the Environment. Currently, the effects of three nanomaterials, Ag, TiO2, and Au, have been investigated. In addition, NANOTEC and NIMT have been collaborating since 2010 to establish quality infrastructure in areas related to nano-scale measurement, calibration, and metrology.

In sum, Thailand is addressing nanosafety concerns in manners that embraces harmonization and enhances the overall goal of technology development. Such technology development and safety awareness need to complement each other in order to achieve sustainable development goals.

3. Examples of nanosafety approaches in other countries

UNITAR supported by the government of Switzerland prepared in a first phase (2012 − 2013) in the countries Nigeria, Thailand and Uruguay and in a second phase (2014–2015) in the countries Armenia, Jordan and Vietnam pilot projects related to the safety of nanomaterials at the national level (SAICM Citation2012b) (). Guidance was being developed by a group of experts from IOMC (UNITAR Citation2011). The guidance was tested in the pilot countries. Pilot project deliverables and key activities included:

Table 1. Pilot projects on nanosafety in selected countries.

undertaking preparatory activities, including identification of a lead agency and key ministries and other stakeholders involved in and interested in nanotechnology issues;

updating of the National Profile for chemicals management to include a new chapter on nanomaterials;

development of a national policy or action plan on the safety management of nanomaterials;

identification of key health and environmental protection‐related priorities concerning nanomaterial safety;

targeted training; and

including nanomaterial safety as part of the country’s national programme for the sound management of chemicals.

3.1. Regional meetings

In 2009 and 2010 in the context of SAICM, a first series of UNITAR/OECD/IOMC nanosafety awareness-raising workshops took place:

in December 2009 for Central and Eastern European countries in Lodz, Poland;

in January 2010 for the African region in Abidjan, Ivory Coast;

in April 2010 for the Arab region in Alexandria, Egypt;

in September 2011 for the Asia-Pacific region in Beijing.

Regional meetings were jointly organized by UNITAR and OECD in 2015 for the African region in Lusaka, Zambia; for the Latin American and Caribbean region in Bogota, Colombia; for the Asia-Pacific region in Bangkok, Thailand. In 2018, OECD and UNITAR organized two workshops, back-to-back with SAICM regional meetings being held in Panama and Poland. In addition, a workshop focusing on Africa and on the Asia-Pacific region was held in Geneva in September 2018.

4. Nanosafety in the global regulatory context

4.1. Early activities, intergovernmental forum on chemical safety

International cooperation on chemical safety after the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 is one of the success stories in international chemical governance (Karlaganis and Perrez Citation2011; Perrez and Karlaganis Citation2012). In response of the invitation of UNCED Agenda 21 to further consider the establishment of an Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety (IFCS), the executive heads of UNEP, ILO and WHO convened in Stockholm 25–29 April 1994 the International Conference on Chemical Safety (ICCS, or Forum I) at the invitation of Sweden and 114 countries, IGOs and NGOs. Intersessional work was guided by the Forum Standing Committee and the IFCS Secretariat, which is located at the WHO. Further Forum sessions were held Forum II in Ottawa 1997, Forum III in Salvador da Bahia 2000, Forum IV in Bangkok 2003, Forum V in Budapest 2006 and Forum VI in Dakar 2008. The meeting reports are available at the websites of WHO (WHO Citation2021) and IISD Earth Negotiation Bulletins (IISD ENB Citation2021).

The Dakar statement on nanotechnology and manufactured nanomaterials was adopted on 19 September 2008 by seventy governments, 12 intergovernmental organizations, and 39 nongovernmental organizations participating in Forum VI of IFCS in Dakar, Senegal (; IFCS Citation2008). The Dakar statement has a preamble and 21 recommendations of the Forum mentioning the precautionary principle and covering, among others, awareness rising, information transfer by material safety data sheets MSDS, occupational health and safety, research, national codes of conduct, legislative frameworks, ISO standards, consumer information and support by Governments, IGOs and NGOs.

Table 2. Dakar statement on manufactured nanomaterials (IFCS Citation2008).

On 6th February 2006 at Dubai, SAICM ICCM 1 adopted the resolution I/3 on the relationship between SAICM and IFCS (; SAICM Citation2006b). While IFCS was never officially closed, and collaboration with the Forum was encouraged at ICCM1, the IFCS no longer exists in a de facto sense. Nonetheless, it serves as a valuable reminder of the early commitment to multi sector and multi stakeholder collaboration. It is encouraging to see discussions in the Beyond 2020 framework reaffirm these commitments.

Table 3. Resolution I/3 ‘Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety,’ adopted 2006 in Dubai by ICCM 1 (SAICM Citation2006b).

4.2. SAICM and emerging policy issues

Adopted by the First International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM 1) on 6 February 2006 in Dubai, SAICM is a policy framework to promote chemical safety around the world (SAICM Citation2021a). SAICM was developed by a multi-stakeholder and multi-sectoral Preparatory Committee and supports the achievement of the 2020 goal agreed at the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development.

SAICM's overall objective is the achievement of the sound management of chemicals throughout their life cycle so that by the year 2020, chemicals are produced and used in ways that minimize significant adverse impacts on the environment and human health. shows the elements of SAICM.

Table 4. SAICM elements which were adopted 2006 in Dubai by ICCM 1.

The Global Plan of Action is a large table, which contains 273 activities (status 2006). As an example, activity 210 is shown in .

Table 5. Activity 2010 as part of the SAICM Global Plan of Action.

One of the functions of the International Conference on Chemicals Management (ICCM) as identified in the SAICM Overarching Policy Strategy (paragraph 24.j) is to call for appropriate action on emerging policy issues as they arise and to forge consensus on priorities for cooperative action. So far, resolutions have been adopted on the following eight emerging policy issues and other issues of concern at ICCM2, ICCM3 and/or ICCM4, as shown in .

Table 6. Emerging policy issues (1–6) and Issues of concern (7 and 8) of SAICM.

Three resolutions were adopted on ‘Nanotechnology and manufactured nanomaterials’ at ICCM2 2009 in Geneva (), ICCM3 2012 in Nairobi (), and ICCM4 2015 in Geneva (), respectively. The resolutions recognize the needs to address identified concerns.

Table 7. Resolution II/4 emerging policy issues, E: Resolution of nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials, adopted by ICCM2 2009 in Geneva (SAICM Citation2009).

Table 8. Resolution III/2 Emerging policy issues, E: Resolution of nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials, adopted by ICCM3 2012 in Nairobi (SAICM Citation2012a).

Table 9. Resolution IV/2 II existing emerging policy issues, D: Resolution of nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials, adopted by ICCM4 2015 in Geneva (SAICM Citation2015b).

In light of these concerns, ‘Nanotechnology and manufactured nanomaterials’ was designated as an emerging policy issue already at the second session of the International Conference of Chemical Management ICCM 2 in 2009 in Geneva (SAICM Citation2009). The decision is based on the resolution adopted also at this conference (). Furthermore, the decision was confirmed by another nano resolution at ICCM 3 in 2012 () and at ICCM 4 in 2015 (). The resolutions primarily aim to improve nano safety in developing countries through appropriate work programmes.

In addition, an amendment of the global plan of action was developed for work activities relating to the environmentally sound management of nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials (; SAICM Citation2012a). A report about the project activities and outcomes in relation to the nano global plan of action GPA and related ICCM3 resolution text was presented at ICCM 4 in 2015 in Geneva (; SAICM Citation2015a).

Table 10. Appendix 1 of Table B of the GPA; Work activities relating to the environmentally sound management of nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials, adopted by ICCM3 2012 (SAICM Citation2012a).

Table 11. Project activities and outcomes in relation to the GPA, presented 2015 at ICCM4 in Geneva) (SAICM Citation2015a).

4.3. SAICM post 2020 and emerging policy issues/issues of concern

SAICM ICCM 4 decided to initiate an intersessional process to prepare recommendations regarding the SAICM and the sound management of chemicals and waste beyond 2020 (SAICM Citation2015b), which created a lot of momentum. Intersessional meetings took place 2017 in Brasilia, 2018 in Stockholm and October 2019 in Bangkok.

The United Nations Environment Assembly UNEA of the United Nations Environment Programme UNEP adopted on the 15 March 2019 the resolution 4/8 on the sound management of chemicals and waste (UNEP Citation2019) and invited the third meeting of the SAICM open-ended working group OEWG 3 (April 2019 in Montevideo Uruguay) to prepare a resolution for ICCM5 about a SAICM post 2020 follow up process. But then came the pandemic, Covid-19 stopped this process and the forth Intersessional Process Meeting (planned for 2020 in Bucharest) and ICCM5 (planned for 2020 in Bonn) were postponed for over 2 years.

The SAICM Bureau wanted to restart this process and to gain momentum again. They created four virtual working groups (VWGs) and organized from November 2020 to February 2021 21 online meetings (English only):

Virtual working group 1 “Targets, indicators and milestones”;

Virtual working group 2 “Governance and implementation”;

Virtual working group 3 “Issues of concern”;

Virtual working group 4 “Financial considerations”.

The SAICM topic ‘Emerging policy issue’ corresponds to ‘Issues of concern’ in the SAICM post 2020 context, which was discussed in the Virtual working group 3. The virtual working group 3 had the following mandate:

Develop proposals for draft procedures for the identification, nomination, selection, review and prioritization of the issues of concern; determining the need for further work on an issue of concern; and duration for considering issues of concern, drawing on experience.

This mandate is on the process only, which is completely different from the SAICM Global Plan of action, which is on substance.

The VWG3 proposed the following definition (SAICM Citation2021b):

An issue of concern is an issue involving any phase in the life cycle of chemicals and which has not yet been generally recognized, is insufficiently addressed or arises from the current level of scientific information and which may have significant adverse effects on human health and/or the environment.

However, the status of the texts resulting from the virtual working groups was not clear in 2021, since negotiations were not allowed during the virtual online meetings. Delegates from countries with bad internet facilities are in disadvantage compared to delegates from industrial countries with high speed internet. In 2021 is was not clear, if theses texts from the virtual working groups can serve as a basis for further physical negotiations.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The safety of manufactured nanomaterials in many industrial countries is meanwhile covered by mainstream chemicals regulation (Karlaganis et al. Citation2019). Other countries have not yet adopted legally binding nanoregulation, but have taken other measures to increase the safety of nanomaterials. Suitable instruments are recommendations, road maps or action plans. These countries have a role as model function and act as regional lighthouses. One such example is Thailand, which has adopted already in 2012 the Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic plan and has a long experience of its implementation. .

Many intergovernmental organisations have been involved in improving the safety of nanomaterials over the last two decades, these are (in alphabetical order) the Basel Convention, ECOSOC, FAO, ILO, IOMC, ISO, OECD, SAICM, UNEP, UNESCO, UNITAR, WHO (see Karlaganis and Liechti Citation2013).

SAICM is an ideal platform to discuss the safety of nanomaterials, because it is a multi-stakeholder and multi-sectoral approach. ICCM2 recognised already in 2009 nanotechnologies and manufactured nanomaterials as an Emerging Policy Issue because it met the criteria required by SAICM. It is therefore not necessary to repeat this evaluation process again. An amendment of the global plan of action for the environmentally sound management of manufactured nanomaterials was adopted at ICCM 3 in 2012. The Global Plan of Action is a concrete proposal on substance with activities, actors, time frame and indicators of progress.

The SAICM post 2020 negotiations were initiated in 2015, were in the beginning rather slow and general and focused on process and not on substance. At the beginning of the SAICM post-2020 negotiations, all participants thought that there was enough time to successfully conclude the negotiations in Bonn in 2020. No one anticipated the years of delays caused by the pandemic. The target year 2020 was missed.

The SAICM ICCM.5 Bureau asked for a legal opinion whether SAICM automatically ends in 2020 based on the ICCM4 resolutions. While the achievement ‘of the 2020 goal’ is expressly referenced in Decision IV/1, the activities requested from the Secretariat are for the consideration of the Conference at its 5th session. No specific date is mentioned. Consequently, SAICM does not end, based upon ICCM 4 resolutions, and reporting is due at ICCM 5, without any specific date being set (SAICM Citation2021c).

In 2022, it was still difficult to predict how and when the negotiation process would resume. SAICM is a success story. It can therefore be assumed that the political will is there to resume the negotiations soon and bring them to a successful conclusion.

In conclusion, the safety of nanomaterials has been discussed by IFCS since 2006 and recognised as an Emerging Policy Issue by SAICM in 2009. Since then, nanosafety has been addressed in many SAICM workshops and conferences. This has improved awareness of nanosafety worldwide. In some countries, such as Thailand, policy and ethics plans have been adopted, which serve as a model for other countries. However, there is still much to be done. Many countries have not yet done anything to implement nanosafety nationally. Therefore, it is important to continue the emerging policy issue of nanosafety in the SAICM post-2020 context as an Issue of Concern without having to go through an elaborate evaluation process beforehand.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest related to this research work.

References

- Basel Convention Coordinating Centre and Stockholm Convention Regional Centre for Latin America and the Caribbean. 2013. Nanotechnology and Nanosafety in Uruguay – Nanoevaluation and Proposal for a Nanosafety Plan – UNITAR Nanosafety Pilot Project (90 Pages). Montevideo, Uruguay: Calaméo Publishing Platform, https://de.calameo.com/read/000255277db18a29c4641.

- IFCS (Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety). 2008. “Final Report Executive Summary of the Sixth Session of the Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety in Dakar, Senegal. Page 8: Dakar Statement on Manufactured Nanomaterials.” https://www.who.int/ifcs/documents/forums/forum6/f6_execsumm_en.pdf.

- IISD ENB (International Institute for Sustainable Development Earth Negotiation Bulletin). 2021. “Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety – IFCS.” https://enb.iisd.org/negotiations/intergovernmental-forum-chemical-safety-ifcs.

- Karlaganis, G., and F. X. Perrez. 2011. “Chemicals Legislation and Policy.” In Berkshire Encyclopedia of Sustainability Volume 3: The Law and Politics of Sustainability, edited by K. Bosselmann, D. S. Fogel, and J. B. Ruhl. Great Barrington: Berkshire Publishing Group.

- Karlaganis, G., and R. Liechti. 2013. “The Regulatory Framework for Nanomaterials at a Global Level: SAICM and WTO Insights.” Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 22 (2): 163–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12031.

- Karlaganis, G., R. Liechti, S. Teparkum, P. Aungkavattana, and R. Indaraprasirt. 2019. “Nanoregulation along the Product Life Cycle in the EU, Switzerland, Thailand, the USA, and Intergovernmental Organisations, and Its Compatibility with WTO Law.” Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry 101 (7–8): 339–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02772248.2019.1697878.

- NANOTEC. 2017. “The Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan 2017-2021.” https://www.nanotec.or.th/en/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Nanosafety-Soft-file.pdf

- NANOTEC. 2021. “The Nanosafety and Ethics Strategic Plan 2021-2024.” https://www.nanotec.or.th/en/?page_id=9279

- Perrez, F., and G. Karlaganis. 2012. “Emerging Issues in Global Chemical Policy.” In Chemicals, Environment, Health, a Global Management Perspective, edited by P. Wexler, J. van der Kolk, A. Mohapatra, and R. Agarwal, 689. Milton Park: CRC Press

- SAICM. 2006a. “About Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) – Overview.” https://www.saicm.org/About/Overview/tabid/5522/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- SAICM. 2006b. “Report of the International Conference on Chemicals Management on the Work of its First Session (ICCM 1), SAICM/ICCM.1/7.” http://www.saicm.org/Portals/12/documents/meetings/ICCM1/Final%20ICCM%20Report%20Eng.pdf

- SAICM. 2009. “Report of the International Conference on Chemicals Management on the Work of Its Second Session (ICCM 2).” SAICM/ICCM.2/15 37 (38): 12. https://www.saicm.org/About/ICCM/ICCM2/tabid/5966/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- SAICM. 2012a. “Report of the International Conference on Chemicals Management on the Work of Its Third Session (ICCM 3).” SAICM/ICCM.3/24 37 (38): 46–50. https://www.saicm.org/About/ICCM/ICCM3/tabid/5963/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- SAICM. 2012b. “Report on Nanotechnologies and Manufactured Nanomaterials.” SAICM/ICCM.3/INF/18. http://www.saicm.org/Portals/12/documents/meetings/ICCM3/inf/ICCM3_INF18_Nano%20Report.pdf

- SAICM. 2015a. “Emerging Policy Issue Update on Nanotechnologies and Manufactured Nanomaterials.” SAICM/ICCM.4/INF/19. http://www.saicm.org/Portals/12/documents/meetings/ICCM4/inf/ICCM4_INF19_Nano.pdf

- SAICM. 2015b. “Report of the International Conference on Chemicals Management on the Work of Its Forth Session (ICCM 4).” SAICM/ICCM.4/15 http://www.saicm.org/Meetings/ICCM4/tabid/5464/language/en-US/Default.aspx.

- SAICM. 2021a. “Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) – Overview.” https://www.saicm.org/About/Overview/tabid/5522/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- SAICM. 2021b. “Proposed Outcome Document – Virtual working group 3 – Process to address Issues of Concern.” Proposal from the co-facilitators of VWG3, draft status 1 February 2021.

- SAICM. 2021c. “Legal Opinion on the Mandate of and the Need for Procedural, Organizational and Administrative Decisions in Advance of ICCM5.” SAICM/ICCM.5/Bureau.TC.8/4. https://www.saicm.org/Portals/12/Documents/meetings/Bureau/ICCM5B16/SAICM_ICCM5-Bureau_TC_8_4_UNEP%20legal%20opinion.pdf

- UNEP. 2019. “Resolution 4/8 Adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly on 15 March 2019 – Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste.” UNEP/EA.4/Res.8. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/28518/English.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y.

- UNITAR. 2011. “Guidance for Developing a National Nanotechnology Policy and Programme.” https://cwm.unitar.org/publications/publications/cw/Nano/UNITAR_nano_guidance_Pilot_Edition_2011.pdf

- WHO (World Health Organisation). 2021. “Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety – Global Partnership for Chemical Safety.” https://www.who.int/initiatives/intergovernmental-forum-on-chemical-safety