Abstract

Objective

A community hospital system covers the entire population of Finland. Yet there is little research on the system beyond routine statistics. More knowledge is needed on the incidence of hospital stays and patient profiles. We investigated the incidence of short-term community hospital stays and the features of care and patients.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

Community hospitals in the catchment area of Kuopio University Hospital in Finland.

Subjects

Short-term (up to one month) community hospital stays of adult residents.

Main outcome measures

The outcome was the incidence rate of short-term community hospital stays according to age, sex and the first underlying diagnoses.

Results

A number of 13,482 short-term community hospital stays were analyzed. The patients’ mean age was 77 years. The incidence rate of short-term hospital stays was 28.6 stays per 1000 person-years among residents aged <75 years and 419.0 among residents aged ≥75 years. In men aged <75 years, the hospital stay incidence was about 40% higher than in women of the same age but in residents aged ≥75 years incidences did not differ between sexes. The most common diagnostic categories were vascular and respiratory diseases, injuries and mental illnesses.

Conclusions

The incidence rate of short-term community hospital stays increased sharply with age and was highest among women aged ≥75 years. Care was required for acute and chronic conditions common in older adults.

Implications

Community hospitals have a substantial role in hospital care of older adults.

Key Points

Finland has a broad network of community hospitals covering the entire population. More knowledge is needed on incidences and patient profiles of community hospital stays.

The incidence of short-term community hospital stays increased sharply with age and was the highest among women aged ≥75 years.

Vascular and respiratory diseases accounted for most of the community hospital admissions.

Community hospitals play an important role in the care of an aging population.

Introduction

The Finnish Social and Health Care System is publicly funded. There are five catchment areas of university hospitals providing tertiary care. These were divided into specialized care districts (n = 21) until 2023. All primary care services were run by municipalities, including about 200 community hospitals as well as home care services and residential care. describes the use of inpatient care in secondary and tertiary care hospitals and in community hospitals in 2016. A large social and health care reform was launched in Finland in the beginning of the 2023 [Citation1,p.3–4]. Community hospital system continued its functioning under the wellbeing services counties (n = 22).

Table 1. Hospital stays and in-patient days by age groups in special level and community hospitals in Finland in 2016.

Community hospitals provide basic level inpatient care mainly for older people who often have multimorbidity and functional limitations. The care is responsive to local needs and is expected to be broad and holistic including assessments and optimization of the patient’s health, functioning and services. Community hospitals are most often led by primary care physicians and staffed by nurses, physiotherapists, ward secretaries and allied professionals such as social workers [Citation2,p.104,Citation3,Citation4]. Community hospitals are located in the near proximity of the health centers, most under the same roofs.

Local community hospitals seek to support people’s ability to live at home. Rehabilitative care in acute and chronic medical conditions enhances functional recovery and the discharge of patients to their own homes [Citation4–6].

Acute illnesses are the main reason for admissions; only one-fourth of admissions are for care after inpatient care in a secondary or tertiary hospital. Other significant tasks of community hospitals include end-of-life care, rehabilitation, providing scheduled interval care and serving as consultation units for home care [Citation3].

In recent years, long-term stays in community hospitals have decreased due to the simultaneous increase in the number of aged care facilities [Citation2,p.104]. In 2016, long-term care represented 17% of community hospital days among patients aged ≥75 years [Citation7]. However, the number of short-term community hospital stays has remained relatively stable despite the centralization of on-call and emergency services, which had been previously provided by all of the over 200 primary health care centers, into secondary and tertiary care hospitals [Citation2,p.104,Citation7,Citation8]. Thus, short-term care in community hospitals plays an important role in the care of an aging population.

The pace of population aging in Finland is among the fastest in the world and Finland is the fastest-aging society in Europe [Citation9,Citation10]. The challenges related to population aging and the increasing use of health and social care services can be seen, e.g. in overcrowded emergency departments and hospital wards, longer waiting times to aged care facilities, rapidly growing work load in home care services and failures in integrated care [Citation11,Citation12,p.333–349].

At the moment, community hospitals are of particular interest due to the ongoing major structural and financial reform of health and social services in Finland [Citation1,p.3–4]. Routinely collected data from the Finnish Care Register (HILMO) provide basic information on the utilization of inpatient care [Citation13,Citation14]. Yet, in order to plan and develop the hospital system and services of older adults, we need more detailed information on incidences and patient profiles of community hospital stays.

We investigated short-term (up to one month) community hospital stays in real-life settings in central and eastern Finland. The specific aims of the present study were to analyze the incidence of short-term hospital stays and to determine the characteristics of patients.

Materials and methods

Setting

The current population in Finland is 5.5 million. The country is sparsely populated especially in its northern and eastern parts. The present survey was conducted in central and eastern Finland in the catchment area of Kuopio University Hospital (KUH), which has 813,000 residents in 65 municipalities. In 2016, when the survey was conducted, the share of people aged ≥75 years was 10.6% in the study area [Citation15]. The community hospital stays represented a fourth (27%) of all adult patients’ hospital stays in the KUH area and a half (48%) of hospital stays among patients aged ≥75 years [Citation7].

The present study involved all community hospitals in the KUH area. Of the 55 community hospital units, 37 were located in rural and 18 in urban surroundings. This distribution was similar to other parts of Finland. Urban community hospitals were located in the same cities that have secondary or tertiary care hospitals. Rural hospitals were usually located further away from population centers and were the only hospitals in the locality. The data collection was carried out between January and June 2016. The duration of the data collection period per hospital unit was 2–4 (mean 3.2, standard deviation (SD) 1.0) months.

Patient selection

All community hospital stays lasting from 1 to 31 days were included in the study. We considered that medical care of acute and chronic conditions fits mainly in one-month time frame. Similar categorization for the short-term care was also used previously [Citation16]. Readmissions of patients were counted as separate hospital stays.

Data collection

We recruited community hospitals by visiting or meeting with the chief physicians. Physicians responsible for treatment, ward secretaries and rehabilitation professionals were jointly responsible for data collection. The data collection was carried out with a structured and standardized electronic survey developed by the researchers. Detailed instructions for how to complete the survey were sent to respondents by e-mail. The survey was completed at the end of each patient’s hospital stay. The data included no personal identifiers [Citation4]. The survey included items identical to the records routinely collected for the Finnish Care Register [Citation13,Citation14,p.15–16]; thus, the personnel were accustomed to report these reliably. In addition, questions concerning the primary reason for the hospital stay, contents of the diagnostic investigations and care, and whether a patient received rehabilitation were asked.

The survey was comprised of 25 questions on the following items: demographics (age and sex, home municipality), hospital unit identifier, date of admission, where the patient came from to the community hospital (secondary or tertiary hospital, residential care, home with or without home care), the primary reason for the hospital stay (acute diseases, chronic diseases, assessment of symptoms, diagnostic investigations), underlying diagnoses, content or goal of the care (management of multimorbidity, continuing care, treatment of a medical complication, starting a new treatment, diabetes management, treatment of pain, wound care, psychiatric care, substance abuse treatment, treatment of poisoning, terminal care, scheduled interval care), specialist consultations, discharge date and destination.

Outcome

The outcome was set as the incidence rate of short-term community hospital stays according to the patients’ age (<75 and ≥75 years), sex and first underlying diagnoses.

The diagnoses were recorded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) classification. The first underlying diagnoses represented the diseases or health conditions assessed as the main cause of the hospital stay [Citation17]. The first underlying diagnoses were reported on a category or subcategory level (e.g. J17* or J18.9) and we aggregated them to a chapter level (e.g. J) to constitute the main groups of diseases and other health conditions.

The patient’s age was calculated by subtracting the number of the year of birth from the number 2016. The incidence of community hospital stays was analyzed by adjusting the number of hospital stays to residents of the same age and sex in the study area. The population data were obtained from Statistics Finland [Citation18].

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means with SDs and counts with percentages. Incidence rates of short-term community hospital stays per 1000 person-years and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated using Poisson’s regression models. The possible non-linear relationship between age and incidence rates was modeled using restricted cubic splines Poisson regression models with 4 knots at the 5th, 35th, 65th and 95th percentiles; knot locations are based on Harrell’s [Citation19] recommended percentiles. The Poisson regression models were tested using a goodness-of-fit test and the assumptions of overdispersion in models were tested using the Lagrange multiplier test. The Stata 17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) statistical package was used for the analysis.

Ethics

The study is primarily organizational research and the subject of the research is the hospital stays. Informed consent was attained from all the 57 community hospitals included in the study. The physicians responsible for treatment collected the data in the end of patients’ hospital stays and the study had no influence on the treatment of patients. The researchers did not have contact with the patients. The data transferred to researchers did not include direct identifiers of the patients, only sex and birth year were recorded. The Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of the North Savo approved the study (approval number 340/2015).

Results

A total of 13,482 community hospital stays were analyzed. The mean age of the patients was 77 (SD 14) years and 55% (n = 7363) were women (). A total of 6137 (46%) patients came to community hospitals through primary care health centers and a clear majority (n = 11,182; 83%) were discharged to their own homes. The majority of patients (71%) were treated in rural community hospitals.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients in short-term stays of community hospital.

The incidence rate of short-term community hospital stays was 28.6 (95% CI: 28.2–29.1) per 1000 person-years among residents under 75 years of age, and 419.0 (414.7–423.4) per 1000 person-years among residents aged 75 years and older. In men under 75 years of age, the incidence was about 40% higher than in women of the same age (IRR 1.41 (1.36–1.45)), but in those aged 75 years and over, the incidence of stays did not differ between the sexes (IRR 0.98 (0.96–1.00)) ().

Table 3. Incidence rates of community hospital short-term stays per 1000 person years.

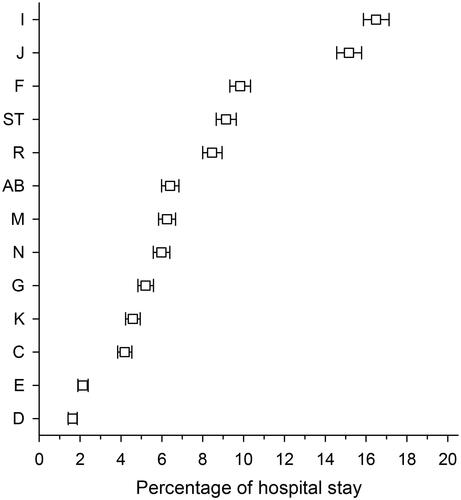

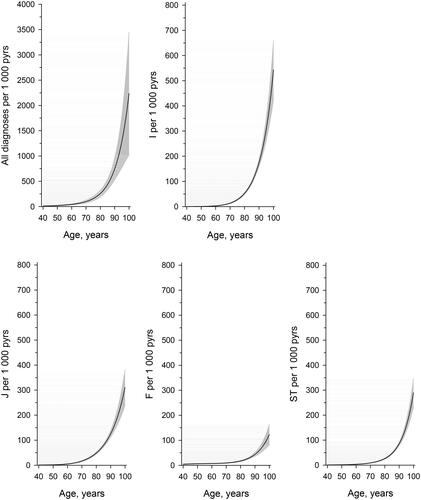

Among short-term hospital stays, the most common first underlying diagnoses were from the chapters of ICD-10 related to circulatory (I) and respiratory (J) diseases, mental and behavioral diseases (F) and injuries (ST) (). The incidence rate was highest and surged with age in the chapter of circulatory diseases (I) (). The most common category-level diagnoses were pneumonia and other respiratory infections (J9–J22, n = 1557; 11.5%), organic mental disorders and other degenerative diseases of the nervous system/dementia (F00–F09; G30–G32, n = 698, 5.2%), heart failure (I50, n = 601, 4.5%) and mental and behavioral disorders related to alcohol use (F10, n = 558, 4.1%). About a third (33.5%) of hospital stays for alcohol-related reasons were short-term detoxification care provided to support cessation of excessive drinking. Within the chapter of injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (S00–T98, n = 1232), the most common category was fractures of the femur (S72, n = 85, 6%).

Figure 1. Proportions of hospital stays by diagnostic chapters. Proportions of community hospital short-term stays by ICD-10 diagnostic chapters*. 95% confidence intervals are marked to the sides of the squares. *I: diseases of the circulatory system; J: diseases of the respiratory system; F: mental and behavioral disorders; ST: injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes; R: symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified; AB: certain infectious and parasitic diseases; M: diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue; N: diseases of the genitourinary system; G: diseases of the nervous system; K: diseases of the digestive system; C: neoplasms; E: endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases; D: in situ and benign neoplasms, neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behavior, diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism.

Figure 2. The incidence rates of short-term community hospital stays per 1000 person-years by age in all and in most common diagnostic chapters circulatory (I) and respiratory diseases (J), injuries (ST) and mental and behavioral diseases (F). The graphs were derived from a 4-knot restricted cubic splines Poisson regression models. The 95% confidence intervals are illustrated with gray color. pyrs: person years; ICD-10 chapters: I: diseases of the circulatory system; J: diseases of the respiratory system; F: mental and behavioral disorders; ST: injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes.

There were some sex-related differences in hospital stay incidences in the most common disease groups (). For example, among men under 75, the incidence due to mental and behavioral disorders (F) was twice as high as among women of the same age (IRR 2.29 (2.12–2.47)). Conversely, incidence due to injuries (ST) was a third lower among men aged 75 years or over than among women (IRR 0.68 (0.63–0.73)). The incidence of short-term community hospital stays due to respiratory diseases (J) was clearly higher in men in both age groups.

Discussion

We investigated the incidence of short-term (up to 1 month) community hospital stays and the characteristics of the patients treated in community hospitals. The incidence of short-term hospital stays increased sharply with age, and it was higher in men under 75 years of age than in women of the same age. The difference leveled off among residents over 75 years of age and furthermore, the incidence was highest among women aged ≥75 years. The most common reasons for community hospital care were vascular and respiratory diseases, injuries and mental illnesses.

A strength of our study was that all the 55 community hospitals participated the survey. Hence, the comprehensive data on hospitalizations and population structure in the study area enabled us to investigate incidence rates of short-term hospital stays among women and men and in different diagnostic categories and diseases and age groups. The hospitals operated normally at the time of data collection and the epidemiological situation of infectious diseases was similar to usual.

The cohort in our study was from a sparsely populated area where morbidity is high. These geographical and demographic characteristics should be considered when generalizing the findings. However, community hospital system exists in several countries and share a lot of common features [Citation20–24].

The care provided by community hospitals is tailored predominantly for older patients with various needs [Citation3,Citation25–27]. In our study, only about a third of hospital stays were needed to treat patients under 75 years of age. Findings from Finland provide a view of what many other countries will experience when their population aging accelerates. The results of our study indicate that there is a need for basic-level hospital care especially for the acute problems and chronic conditions of older people.

According to our results, the most common underlying diagnoses were from ICD chapters on vascular and respiratory diseases. This was in line with a Swedish study reporting that pneumonia and heart failure were the most common main diagnoses for hospital stays in rural community hospitals [Citation28]. Injuries and mental illnesses also resulted in a large number of community hospital stays in the KUH area. These findings were in line with the burden of disease in older people worldwide [Citation29].

In our study, the incidence of hospital stays due to respiratory diseases was more common among men both under and over the age of 75 than among women. Pulmonary diseases are more common and begin at an earlier age in men than in women [Citation30]. Some previous studies have found that men needed more hospitalization than women due to pneumonia [Citation28,Citation31]. Underlying factors probably include smoking and the higher morbidity of chronic pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases.

We also found that men needed more short-term hospital stays due to mental and behavioral diseases than women did, and most of these were explained by the harmful use of alcohol. Alcohol consumption and both acute and long-term complications of alcohol use are more common among men [Citation30,Citation32].

In the present study, women aged ≥75 years required hospitalization due to injuries and musculoskeletal disorders more often than men did. It is known from previous research that osteoporotic fractures are more common among women [Citation33]. In addition, the risk of falling has been shown to be higher among older home-dwelling Finnish women than among men [Citation34]. It is also known that low back pain, osteoarthritis and other musculoskeletal disorders are more common in women than in men, and the gap increases with age [Citation29,Citation35,Citation36].

A significant share of diagnoses was from the ICD-10 chapter of symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings (R). This may reflect situations in which an older adult’s functional capacity is reduced, but no single specific diagnosis can be established or there may be many underlying reasons for the decrease in functional capacity.

There is a discussion as to how to prepare to deliver person-centered, high-quality hospital care to meet the needs of aging populations [Citation21,Citation37,p.16–18]. Winpenny et al. stated that community hospitals’ ability to play an integrative role in local services by co-working with other primary care services and secondary and tertiary hospitals is important in the health service system of older adults in the future [Citation27]. The Finnish Community Hospital System has many roles such as treatment of acute and chronic conditions, end-of-life care, rehabilitation and close collaboration with home care and residential aged care services. Above all, they provide a substantial amount of acute and subacute hospital care for older patients. An advantage of community hospitals is their proximity to patients’ homes and knowledge of local services. Care in community hospitals has been reported to be more holistic and integrated compared with care in general hospitals [Citation21,Citation28]. Consequently, community hospitals have a substantial role in supporting the coordination and continuity of care for older people. Continuity of care is associated with a lower need for out-of-hours services, hospitalization and cost [Citation38–41].

Population aging leads to an epidemic of chronic conditions. The leading contributors of disease burden worldwide are cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, musculoskeletal diseases and neurological and mental diseases [Citation29]. These same diseases, along with infectious diseases and injuries, were the leading causes of short-term community hospital stays in this study. The question remains whether the role of community hospitals could be a better-identified and strategic part of managing the effects of population aging. Currently, the role of community hospitals is neither determined nor prioritized in rapidly ageing Finland. New wellbeing services counties started to provide primary care services (including community hospitals, home care and residential care) in the beginning of 2023. At the moment, there are considerable challenges in financing social and health care services. At the same time, there are growing shortages of health care personnel. Emergency departments and many wards in secondary and tertiary care hospitals are overcrowded while community hospitals are under pressure to be reduced in the number of units and beds [Citation1,p.8]. Considerations and contradictory arguments about the role of community hospitals have aroused in several countries [Citation20–23,Citation42]. At least, the care in community hospitals is less expensive than in secondary or tertiary hospitals and may better meet the broad care needs of older patients. Average costs of inpatient day in a Finnish community hospital are about one-third that of inpatient day in secondary or tertiary care hospital [Citation43]. Cost control has been a major reform motivator in the health care. Yet, cutting down services at one sector tend to cause crowd and dissatisfaction to another [Citation44]. Cost-effectiveness of the community hospital care, however, needs further evaluation.

Our study showed the incidences and clinical profiles of community hospital stays. The incidence of short-term community hospital stays increased sharply with age. Community hospital care is needed for the treatment of acute and chronic conditions common in old age, such as pneumonia and heart failure. There were sex-related differences in the incidence of hospital stays, which are probably explained by differences in morbidity.

Community hospitals have a substantial role in the hospital care of older patients. Aging societies should develop and enhance the role of community hospitals in the care of acutely ill older adults.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tynkkynen LK, Keskimäki I, Karanikolos M, et al. Finland: health system summary. European health systems and policies. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2023. p. 3–4 [cited 2023 Nov 11]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/366710

- Keskimaki I, Tynkkynen LK, Reissell E, et al. Finland: health system review. Health system in transition. Vol. 21. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327538

- Saari H, Lönnroos E, Mäntyselkä P, et al. Mitä on Perusterveydenhuollon lyhytaikainen sairaalahoito? [What are the characteristics of short-term in-patient care in Finnish primary care hospitals?]. Finn Med J. 2019;44:2506–2518.

- Saari H, Ryynänen OP, Lönnroos E, et al. Factors associated with discharge destination in older patients: Finnish Community Hospital Cohort Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(11):1868.e1–1868.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.07.004.

- Young J, Green J, Forster A, et al. Postacute care for older people in community hospitals: a multicenter randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01456.x.

- Green J, Young J, Forster A, et al. Effects of locality based community hospital care on independence in older people needing rehabilitation: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331(7512):317–322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38498.387569.8F.

- Statistical information on welfare and health in Finland; 2023 [Internet]. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [cited 2023 Nov 11]. Available from: https://sotkanet.fi/sotkanet/fi/haku?q=perusterveydenhuollon%20vuodeosastohoito

- Health Care Act 1326/2010. § 50a issued in Helsinki; 2010 [Internet]. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health [cited 2023 Aug 31]. Available from: https://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2010/en20101326.pdf

- Elderly population [Internet]. OECD iLibrary; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: doi: 10.1787/8d805ea1-en.

- Pirhonen J, Lolich L, Tuominen K, et al. “These devices have not been made for older people’s needs” – older adults’ perceptions of digital technologies in Finland and Ireland. Technol Soc. 2020;62:101287. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101287.

- Valkama P, Oulasvirta L. How Finland copes with an ageing population: adjusting structures and equalising the financial capabilities of local governments. Local Gov Stud. 2021;47(3):429–452. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2021.1877664.

- Karvonen S, Kestilä L, Saikkonen P. Suomalaisten hyvinvointi 2022 [Well-being of Finns 2022]. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2022. Available from: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-996-2

- Care register for health care [Internet]. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health; 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 31]. Available from: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/statistics-and-data/data-and-services/register-descriptions/care-register-for-health-care

- Kajantie M, Manderbacka K, McCallum A, et al. How to carry out register-based health services research in Finland? Compiling complex study data in the REDD project. Helsinki: STAKES; 2006. Available from: julkari.fi

- Statistical information on health and welfare in Finland; 2023 [Internet]. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [cited 2023 Aug 31]. Available from: https://sotkanet.fi/sotkanet/en/taulukko/?indicator=szbyAAA=®ion=s061AAA=&year=sy4rBwA=&gender=t&abs=f&color=f&buildVersion=3.1.1&buildTimestamp=202211091024

- Saukkonen S, Vuorio S. Perusterveydenhuollon vuodeosastohoito vuosina 2015–2016 [Inpatient care in primary health care in 2015–2016]. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2017. Available from: perusterveydenhuollon vuodeosastohoito vuosina 2015–2016 (julkari.fi)

- Komulainen J. Suomalainen tautien kirjaamisen ohjekirja [Finnish manual for recording diseases]. Tampere: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2012. Available from: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/70398/URN_ISBN_978-952-245-511-6.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Statistics Finland’s free-of-charge statistical databases. Helsinki: Statistics Finland; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: https://pxdata.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__vaerak/?tablelist=true

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001.

- Seamark D, Davidson D, Ellis-Paine A, et al. Factors affecting the changing role of GP clinicians in community hospitals: a qualitative interview study in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(682):e329–e335. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X701345.

- Davidson D, Ellis Paine A, Glasby J, et al. Analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient experience and community value of community hospitals: a multimethod study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2019;7(1):1–152. doi: 10.3310/hsdr07010.

- Frakking T, Michaels S, Orbell-Smith J, et al. Framework for patient, family-centred care within an Australian community hospital: development and description. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(2):e000823. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000823.

- Charante EM, Hartman E, Yzermans J, et al. The first general practitioner hospital in The Netherlands: towards a new form of integrated care? Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004;22(1):38–43. doi: 10.1080/02813430310004939.

- Ekanem E, Fajola A, Usman R, et al. Management of epilepsies at the community cottage hospital level in a developing environment. Niger Med J. 2019;60(4):186–189. doi: 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_6_18.

- Heaney D, Black C, O’Donnell CA, et al. Community hospitals—the place of local service provision in a modernising NHS: an integrative thematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):309. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-309.

- Pitchforth E, Nolte E, Corbett J, et al. Community hospitals and their services in the NHS: identifying transferable learning from international developments – scoping review, systematic review, country reports and case studies. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2017;5(19):1–220. doi: 10.3310/hsdr05190.

- Winpenny EM, Corbett J, Miani C, et al. Community hospitals in selected high income countries: a scoping review of approaches and models. Int J Integr Care. 2016;4:1–13.

- Hedman M, Boman K, Brännström M, et al. Clinical profile of rural community hospital inpatients in Sweden – a register study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021;39(1):92–100. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2021.1882086.

- Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet. 2015;385(9967):549–562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61347-7.

- Koponen P, Borodulin K, Lundqvist A, et al. Terveys, toimintakyky ja hyvinvointi Suomessa: FinTerveys 2017 – tutkimus [The FinnHealth 2017 Survey – report]. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2018.

- Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for pneumonia in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl. 7):S570–S576. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz053.

- Shield K, Manthey J, Rylett M, et al. National, regional, and global burdens of disease from 2000 to 2016 attributable to alcohol use: a comparative risk assessment study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e51–e61. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30231-2.

- Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, et al. The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br Med Bull. 2020;1:105–117.

- Luukinen H, Koski K, Hiltunen L, et al. Incidence rate of falls in an aged population in Northern Finland. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(8):843–850. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90187-2.

- Vina ER, Kwoh CK. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30(2):160–167. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000479.

- Wu A, March L, Zheng X, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(6):299. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.175.

- Health at a glance Europe 2012. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2012. Available from: doi: 10.1787/9789264183896-en.

- Sandvik H, Hetlevik Ø, Blinkenberg J, et al. Continuity in general practice as predictor of mortality, acute hospitalisation, and use of out-of-hours care: a registry-based observational study in Norway. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;72(715):e84–e90. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0340.

- Barker I, Steventon A, Deeny SR. Association between continuity of care in general practice and hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: cross sectional study of routinely collected, person level data. BMJ. 2017;356:j84. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j84.

- Baker R, Bankart MJ, Rashid A, et al. Characteristics of general practices associated with emergency-department attendance rates: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(11):953–958. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.050864.

- Chao YH, Huang WY, Tang CH, et al. Effects of continuity of care on hospitalizations and healthcare costs in older adults with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):724. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03407-7.

- Aaraas I, Langfeldt E, Ersdal G, et al. The cottage hospital model, a key to better cooperation in health care – let the cottage hospital survive! Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2000;120(6):702–705.

- Mäklin S, Kokko P. Terveyden- ja sosiaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2017. [Unit costs of health and social care in Finland in 2017]. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2020. Available from: Terveyden- ja sosiaalihuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2017 (julkari.fi)

- Tjerbo T, Hagen TP. The health policy pendulum: cost control vs activity growth. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(1):e67–e75. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2407.