ABSTRACT

This study adds to the literature on the gendered culture of the forest sector by examining testimonies of sexual harassment in relation to the gendering of forestry-related competence and organisations and the consequences that the sexualisation of social relations in organisations has, mainly for women. The empirical base of the study comprised testimonies within the campaign #slutavverkat published on Instagram to highlight experiences of sexual harassment of women in the Swedish forest sector. Qualitative content analysis of the testimonies suggested that the situations described in the testimonies in #slutavverkat comprise controlling actions that diminish women’s power in the forest sector. Sexualised forms of male control and harassment thus work to remind women that they are first and foremost a representation of women, rather than of forestry professions and knowledge. In that sense, sexualised forms of male control and harassment are part of, rather than deviating from, the overall gendering of forestry as a men-dominated sphere. The study adds to organisational understandings and policy developments on discrimination and harassment and suggests that researchers and policy-makers interested in reducing inequality in forestry need to pay more attention to issues of harassment and sexualisation of social relations.

Introduction

Enough now.

We are tired of being diminished, attenuated and sexually objectified.

We are tired of sexist comments, jokes and jargon.

We are tired of being subjected to intimidation and dictatorial techniques.

We are tired of sexual harassment and assault.

[…]

Our wish is that our managers and male and female co-workers read our stories and start to talk with each other about how we, together, can change the situation. The culture of silence must be broken. As must macho culture and power structures.

This declaration of intent is part of the appeal #slutavverkat (clear-felled), a campaign against sexual harassment taking place in the Swedish forest sector. The appeal relates to the hashtag #MeToo, coined by the Afro-American feminist Tarana Burke in 2006. It went viral in October 2017 when the American actress Alyssa Milano called upon all who have been sexually harassed to demonstrate the magnitude of the problem by leaving the comment “me too” on her tweet. While #MeToo became heavily debated in many countries, what sets Sweden apart is the vast number of industry-specific campaigns that it created. The first was on 8 November 2017, when more than 700 Swedish actresses published the appeal #tystnadtagning (keeping silent), describing the sexual harassment they had witnessed or been subjected to within the film and television industry. In addition to the signatures and a letter of intent emphasising the need to break the “culture of silence” and take action against misogynist structures, the responses included numerous graphic testimonies by individuals about the harassment they had suffered. The appeal gained massive attention and, in its wake, similar appeals emerged calling for women, based on their profession, industry or other interests, to witness and protest against the sexual harassment they had experienced. By the end of 2017, more than 50 such campaigns had emerged from different parts of the Swedish labour market and society as a whole. Hence, when #slutavverkat was launched, this occurred in the context of previous campaigns and the “genre” these had created. Since @slutavverkat started on 17 December 2017, testimonies of individuals describing assault and harassment in the forest sector have been published on Instagram. By 26 January 2018, 100 testimonies had been published, with more to come. The industry-specific campaigns created by #MeToo indicate that, while a pattern of gender hierarchies exists throughout working life, the specific ways in which sexual harassment and assault are played out depend on the specific conditions and circumstances in the respective industry. Hence, #MeToo has the potential to add to existing knowledge and understanding on reproduction of inequalities within specific industries. From a research perspective, the many debates and initiatives relating to the #MeToo campaign appear to have the potential to add insights on the reproduction of inequalities within specific contexts. As time passes, this potential is likely to be translated into scientific productions, but as yet #MeToo has only resulted in short comments and reflections (Corcione Citation2018; Zarkov and Davis Citation2018).

There is a body of existing literature on dominant masculine culture and its implications for the work organisation and for individual men and women in the forest sector (e.g. Follo Citation2002; Brandth et al. Citation2004; Brandth and Haugen Citation2005; Lidestav Citation2010; Coutinho-Sledge Citation2015; Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016; Johansson et al. Citation2017). However, little attention is directed toward sexuality or the more violent aspect of masculine culture, so analyses of #MeToo and #slutavverkat are justified. The existing literature shows that the homogeneity and common cultural perceptions in the forest sector influence how work is understood and organised and how knowledge is valued and transmitted (cf. Follo Citation2002). By simply deviating from the masculine norms, women are not expected to possess the right kind of skills or knowledge and are expected to need additional help, so they become invisible as carriers of knowledge (Lidestav et al. Citation2011). The dominance of men in the sector is pervasive and constructions of certain forms of masculinity are key regarding the conceptions of who “knows forestry” (Brandth and Haugen Citation2000, Citation2005). To address this research gap, this study set out to analyse and discuss the testimonies within #slutavverkat as a potential aid to understanding the gendered structures and notions of organisations in the Swedish forest sector. Apart from adding important insights on the entwinement of sexualised forms of male control and gendered organisational inequalities in (forest-related) workplaces, the study sought to provide suggestions on improving organisational understanding and policy development on discrimination and harassment.

Material and methods

This study draws upon stories of sexual harassment in the forest sector published on the social media platform Instagram, under the appeal #slutavverkat. Social media is commonly defined as “a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of User Generated Content” (Kaplan and Haenlein Citation2010, p. 62). In 2010, over 75% of all internet users also used social media, and the numbers are still rising for all ages. This kind of digital platform facilitates information sharing and collaboration among people. In the case of #slutavverkat, “women and non-binary in the Swedish forest sector”, including employees, former employees and students, were invited to share their stories on the Instagram account @slutavverkat. The first 100 stories published between 19 December 2017 and 26 January 2018 were analysed in this study. Together, the stories amount to almost 10 000 words. The uniqueness of this dataset relies on the anonymity of those testifying, but because of this we have no further information on the individuals who contributed as regards geographical spread, age, education level and so forth than what is shared in the stories. The testimonies also reveal very little regarding the timeframe and location of the events and experiences mentioned. In general, the stories reveal very little about the individuals behind posts or about the perpetrators and bystanders mentioned in the testimonies, although some are signed with a job title such as forester and/or an organisational affiliation.

When exploring a phenomenon that is sparsely researched, such as sexual harassment and sexualised forms of male control in the forest sector, conventional content analysis is useful, since it starts with the empirical material and allows the categories and themes to be derived from the data set (Krippendorff Citation2004; Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). Thus, in the present analysis, all 100 testimonies were first gathered and individually coded inductively by all three researchers, based on patterns, meaning units and communalities in the material. Triangulation of the individual coding was then carried out, followed by an additional deductive coding on the basis of the analytical framework. Through this process, extracted codes and categories were analysed and structured into three main themes: What?, Where/when? and How?, as illustrated below ().

Figure 1. Examples from the analytical procedure, where each theme is illustrated with some of its subcategories and codes.

The emphasis in the analysis was on meaning making, patterns and commonness, applying a perspective where language is understood as constitutive, rather than descriptive, of the lived reality. No generalisation or quantitative measurements concerning “how many” or “how often” were derived based on the testimonies. Instead, the study offers a deeper understanding of how inequality and sexual harassment are understood in the everyday (working life) experiences of women in the forest sector and how meaning makings of sexual harassment reciprocity are constructed in relation to gendered structures and notions of forestry organisations.

Analytical framework: situating men’s violence in organisations

Sexual harassment concerns “the unwanted imposition of sexual requirements in the context of a relationship of unequal power” (MacKinnon Citation1979, p. 1). According to Kensbock et al. (Citation2015, p. 37) this covers a continuum of practices, “ranging from verbal comments, jokes and sexual gestures, to actions encompassing touching, coercive attempts to establish a sexual interaction and rape”. In the present study, sexual harassment is based on the understanding of sexuality as part of the ongoing production of gender (Acker Citation1992), which forms gendered interactions and relations through sexualised forms of male control, particularly in men-dominated industries and organisations (Collinson and Collinson Citation1989, Citation1996; Cockburn Citation1991; Witz et al. Citation1996; Bagilhole Citation2002; Paap Citation2006; Watts Citation2007). In this way, sexuality surfaces as a means of control over women (e.g. Collinson and Collinson Citation1996; Bagilhole Citation2002; Watts Citation2007; Wright Citation2016), as an integral part of organisational life (e.g. Hearn et al. Citation1989; Hearn and Parkin Citation2001) and as the institutionalisation of heterosexuality (Ingraham Citation1994). In the workplace, sexuality is used by men to demonstrate their masculinity (Paap Citation2006) and to define femininity on the basis of heterosexual norms. Within the conceptualisation of body politics, describing how the relations and interactions of men and women are materialised though the “lived body”, sexual harassment is perceived as a violation of bodily integrity structured along verbal, spatial and physical dimensions. These dimensions include verbally calling up bodies and sexuality, physically violating the symbolic space (notion of “personal space”) and enforcing/governing the spatial segregation (exclusion) of and between bodies (Cockburn Citation1991). These concepts support the analytical process of identifying discourses of difference (negative representations that e.g. set limitations) and discourses of differentiation (positive representations that e.g. emphasise complementary relations and notions) linking the sexual politics of organisations/workplaces to body politics (Witz et al. Citation1996). As such, sexual harassment should not only be seen as a practice of subordinating women in the workplace, but as “an individual appropriation, a ‘taking’ of women’s bodies” (Cockburn Citation1991).

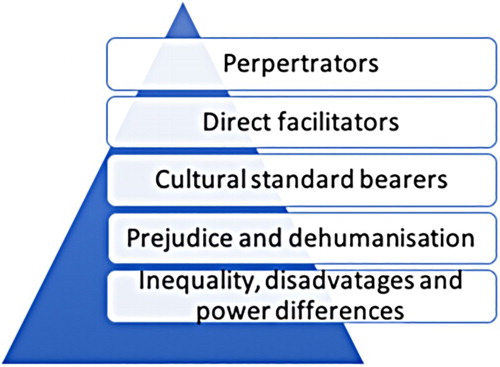

One way to illustrate the relationship between sexualised forms of male control and their organisational context is the cultural-systematic perspective offered by Kilmartin (Citation2014, Citation2015). Using a pyramid (), Kilmartin demonstrates how gender-based violence, sexual harassment included, is not likely to arise without social support. At the top of the pyramid are the perpetrators, who harass, abuse and ultimately murder women. Below them in the pyramid are the direct facilitators, such as the silent bystanders who keep from intervening when violence occurs. Supporting the direct facilitators are the cultural standard bearers, those influential voices in specific cultures repeatedly expressing disrespectful attitudes towards women. This is in turn is supported by prejudice and dehumanisation. Sexist attitudes towards women are found in large parts of society and examples of prejudice and dehumanisation involve mechanisms such as objectification of women and victim blaming (Nussbaum Citation1995; Langton Citation2009). At the base of the pyramid is inequality, disadvantage and power differences. It can be argued that gender-based violence will not come to an end until its foundation is eroded (Kilmartin Citation2014, Citation2015).

Figure 2. Illustration of the pyramid model of gender-based violence (Kilmartin Citation2014, Citation2015).

Understanding men’s violence, such as sexual harassment, against women from a structural perspective rather than as a matter of individual actions does not exclude notions of agency and resistance. Among studies of women trying to “handle” or “manage” male sexuality (Wright Citation2013, Citation2016), some have shown how women who deviate from cultural norms find it easier to gain acceptance as “one of the guys” through bonding and identifying with men over masculine interests and activities (Wright Citation2008; Denissen and Saguy Citation2014). Through this, they distance themselves from typical “femininity” (Martin Citation2001) and are marked as sexually unavailable (McDowell Citation1997; Paap Citation2006). On the basis of agency, the #MeToo and #slutavverkat campaigns can be viewed as acts of resistance in a cultural system that ordains silence and complicity (cf. De Welde et al. Citation2015). In relation to the forest sector, women’s networks are examples of agency and resistance highlighted in research (Brandth et al. Citation2004; Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016).

Results

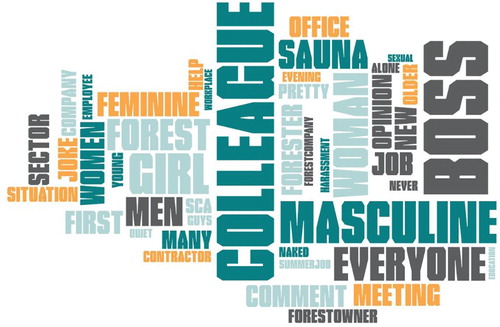

The #slutavverkat testimonies provide fruitful insights when viewed as discursive resistance practices, as they are central to the experiences of the participating women. The analysis uncovered a number of recurring themes and issues among the stories. The first theme, What? (Objects of male desires – difference and differentiation), describes the characteristics of the sexual harassment reported through the stories. The second theme, Where/When? (Unsafe spaces – gendered spaces), elaborates on the time and place of the events reported. The third theme, How? (Reproducing practices and resistance), considers whether sexual harassment is connected to the gendered practices and gendered culture of the forest sector. These themes partly overlap, as all episodes described can be explored in relation to when and where, just as all episodes are examples of how sexist structures in the Swedish forest sector are reproduced. To illustrate the material, a word cloud () was created to highlight similarities and the key words used by the women to describe their experiences. This representation revealed the recurrence of gender and workplace relations in the testimonies, as well as specific places and practices frequently described.

Theme 1: objects of male desires – difference and differentiation

A prominent pattern in the stories was how objectification of women is used in a wide range of situations varying from “heedless compliments” to studious attempts resulting in silenced and scared women. Story 26 problematises heedless compliments by explaining that even though her supervisor and colleagues “probably meant well”, it was highly unwelcome to listen to judgments concerning her own body from men she will be spending much time with in remote forests. This violation of bodily space resulted in feelings of discomfort and insecurity. Another story describes the conversation between two managers where the objectification is no longer masked as a compliment, but shows contempt and disrespect:

There are two reasons why he gave that girl the job, her left and her right boob. (Story 16, #slutavverkat)

Aside from experiences of being objectified, diminished and ridiculed, some of the stories in #slutavverkat bear witness to sexual harassment and sexual violence. In many of the stories, the ways in which sexual harassment and sexual violence are mentioned indicate that these seem widespread and “naturalised” as practices women in the industry need to accept and take into account. Story 79 states that during 10 years in the company, “not once have I escaped a tap on the butt at the annual Christmas party” meaning that the bodily integrity of women is continually violated. Story 19 tells how an older male colleague approached a woman after a company dinner:

He came up to me and said: “Can I give you a hug?”. At the same second as he said it, he both hugged me and gave me a wet kiss on my cheek. I didn’t have time to react or answer his question, and he had me in a firm grip. How can anyone just do like that, and totally without my consent? (Story 19, #slutavverkat)

When she dared to talk to her boss, she was told that she just had to put up with it. Both the boss and the perpetrator are still with the company and what happened was hushed up. (Story 5, #slutavverkat)

Theme 2: unsafe spaces – gendered spaces

The where and when, or the time and space of sexual harassment and assaults in the forest sector, are not always explicitly described in #slutavverkat. Occasions described in relation to sexist comments and remarks include everyday organisational activities such as job interviews, meetings or coffee breaks where women interact with men, without these comments and remarks being challenged by the other people present. Field work and interactions with forest owners also seem to be perceived as unsafe spaces for women:

Daily comments about my breasts and my bum and what they would do to me behind the pile of brushwood. (Story 66, #slutavverkat)

In this industry, there is always sauna baths. As soon as there is a social activity of some sort, sauna bathing happens. Sauna bathing was my first social activity as a new employee at XXX. When I came into the sauna, a number of naked men over the age of 50 were sitting there. Some had the good taste to have a towel, one used bathing shorts. But the first time I met some of my co-workers, they were naked and sweaty. That situation is not ok. Respecting them after that is difficult. I wonder how the organisation can allow this? After that one time, I stopped participating in sauna baths. I am often the only women and this [avoiding the sauna] makes me feel excluded from social events. While the men socialise, I do something else, go to my room, take a walk, e-mail, make calls or wait in the relaxing area (if such exists). This means that the men in the sauna baths have conversations that I am not part of. When I meet them later, I always feel left out. (Story 17, #slutavverkat)

Theme 3: reproducing practices and resistance

The third recurring theme in the stories gives insights into how these inequalities and harassment are reproduced as part of the culture of both the sector and its organisations. They provide examples of how these behaviours and sexist practices are normalised, how men and women are socialised into the culture and how women, within the sector, have developed various forms of strategies to handle the situations (cf. Wright Citation2013, Citation2016). A great number of the stories describe how men are established as the norm and blame is placed on women, who have to “suit themselves” and be able to stand sexist jokes and verbal and physical harassment, with expressions such as “you have to have a thick skin” and “you can’t be so sensitive”. One of the women in #slutavverkat describes her men colleagues’ perspective:

She knew what she was getting into when she picked the forest. Then you actually have to stand the jargon that we have in this group. (Story 60, #slutavverkat)

I was told by an older forester that I had the possibility to make it in this sector, partly because I was a woman (…) and partly because I wasn’t like the other women. I couldn’t be “too sensitive”, because then I wouldn’t last long. I had to be able to take jokes or let them pass – then could I make it far. (Story 72, #slutavverkat)

Being the only girl among nine guys at the forestry secondary school, the only strategy that worked for me was to be twice as hard as the guys – by telling even dirtier jokes and ignoring groping. I quite quickly noticed that if I gave in to their harassment and was affected, then they would have won. Instead, I built a shield where I became the cool girl who had a “thick skin” and could stand sex jokes, in contrast to other “sourpusses”. (Story 90, #slutavverkat)

Discussion

Analysing the stories in the #slutavverkat campaign about the issue of sexual harassment in the Swedish forest sector revealed both the sexuality and the body politics of its organisations. In this context, the various forms of sexual harassment included in the testimonies can be viewed as controlling gestures that diminish women’s sense of power in the sector. As such, they function to remind them that they are “only” women in an organisation in which “men’s sexuality and organisational power are inextricably linked” (Collinson and Collinson Citation1989).

Using the cultural-systemic model in which gender-based violence is conceptualised as a pyramid (cf. Kilmartin Citation2014; Kilmartin Citation2015), the #slutavverkat testimonies can be traced to all of the levels described. The perpetrators are described there, as are the silent bystanders and the prejudice culture in which women are reduced to their bodies. Some of the testimonies, Story 5 for example, clearly demonstrate the culture of silence, which is crucial for the persistence of sexual harassment and violence (De Welde et al. Citation2015). In Story 5 the manager was a direct facilitator, allowing sexual harassment to take place (cf. Kilmartin Citation2015). By acting as though it never happened, the manager was able to avoid dealing with the specific perpetrator and with the workplace culture in which such behaviours are made possible. The effects of these body politics are also described in the ways in which women navigate around and manage men, and men’s sexuality, to avoid feeling unsafe in certain spaces. In all, the stories improve understanding of how the body politics of the Swedish forest sector structure and reproduce a culture, through both formal and informal occasions/events, that maintains the dominance of men by limiting safe and inclusive spaces and cultures for e.g. women.

Due to the specificity of the empirical data, the results have some constraints and weaknesses in relation to the limited number of observations. The 100 testimonies provide unique insights on the gendering of the forest sector and the consequences of this, but are nevertheless a limited source of knowledge, which prevents generalisation to the Swedish forest sector at large. The data set does not give any further information on the actors and events described than what is open for all to read in social media. The data analysis method applied also has its limitations in capturing the full nuances of the processes described. Nevertheless, commonalities and patterns found in the material and indicated in previous research offer important contributions to understanding organisational inequalities in the forest sector. In a scientific context, this study adds to existing findings on how matters of sexuality and gendered-based violence are entwined in the gendering of forestry professionals and organisations (cf. Kilmartin Citation2014, Citation2015). Johansson et al. (Citation2017) show that for some male forestry professionals, the assumed association between forestry skills and men’s bodies results in hiring and promotion of women professionals being perceived as affirmative action and a deviation from meritocratic principles. Johansson et al. (Citationforthcoming) show that one consequence of the gendered constructions of forestry knowledge in relation to a certain type of men and masculine is that women professionals are assumed to lack technical skills until they prove their knowledge. Similar results have been reported in relation to forest ownership (Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016). The present study demonstrates an additional aspect of the general lack of belief in the technical ability of women forestry professionals to do their job, namely the tendency to frame their success not as proof of their practical ability, but as proof of their sexual desirability.

This study also reveals that the sexualisation of social relations in organisations has consequences for women, particularly in men-dominated organisations. By structuring different bodies within different spaces, the practices and processes of body politics provide various subject positions and associate them with particular meanings and thus particular spaces of action and agency (cf. Cockburn Citation1991). By associating bodies and meanings, the stories in #slutavverkat give examples of how these practices both embrace and exclude bodies, by making some “the norm” and others deviant. Men’s bodies are placed in the centre, by e.g. being naked in the sauna, taking up space at meetings and making women the subject of sexual desire in both the forest and the office. As “men call up women’s embodiment in ways which diminish their competence and authority” (Witz et al. Citation1996), women are socially forced to adapt to male norms, handle male sexuality, give up their bodily notions of personal space and, to a higher degree, prove their wordiness/competence. Through the discourses of difference and differentiation, women and their bodies in the Swedish forest sector are structured by male heterosexuality through complementary representations (cf. Ingraham Citation1994; Follo Citation2002; Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016). With the objectification of women’s bodies, processes of segregation and exclusion separate them from the dominant male body and its symbolism of forestry knowledge (cf. Brandth et al. Citation2004; Brandth and Haugen Citation2005; Lidestav Citation2010; Coutinho-Sledge Citation2015; Andersson and Lidestav Citation2016; Johansson et al. Citation2017). This study revealed the entwinement of sexuality and gendered-based violence with the gendering of forest-related competence and organisations, and the consequences that the sexualisation of social relations in organisations has, mainly for women, However, there is still a need for further research on how these mechanisms function and are made sense of (naturalised) in the everyday organisational life.

The study points to the need for policy-makers and employers to intensify and broaden the scope of gender equality interventions in the forest sector. According to Acker (Citation2006), sexual harassment can be viewed as informal interactions while “doing the work”, and need to be better understood when addressed by formal policy interventions (Acker Citation2006; Healy et al. Citation2011). Previous research has shown a tendency in the forest sector to focus on antidiscrimination and routines for handling sexual harassment (Johansson and Ringblom Citation2017; Andersson et al. Citation2018). Important as this is, it can nevertheless be concluded from #slutavverkat that it does not seem to be enough. The results of this study highlight the need to pay more attention to sexuality within research on the forest sector and its organisations, in order to better understand its gendering and cultural processes – and potentially challenge these. With reference to a cultural-systemic perspective on men’s violence against women, we recommend that, in their future work, research and forestry organisations target the mechanisms that make room for sexist behaviour and harassment in forestry-related workplaces and in forestry education. We also strongly emphasise a need to account for men’s responsibility in upholding a culture where this can take place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Acker J. 1992. Gendering organizational theory. In: Mills AJ, Tancred P, editors. Gendering organizational analysis. Newbury Park: Sage; p. 248–260.

- Acker J. 2006. Inequality regimes: gender, class, and race in organizations. Gend Soc. 20(4):441–464. doi: 10.1177/0891243206289499

- Andersson E, Johansson M, Lidestav G, Lindberg M. 2018. Constituting gender and gender equality through policy: the political of gender mainstreaming in the Swedish forest industry. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal. (Accepted).

- Andersson E, Lidestav G. 2016. Creating alternative spaces and articulating needs: challenging gendered notions of forestry and forest ownership through women’s networks. Forest Policy Econ. 67(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2016.03.014

- Bagilhole B. 2002. Women in non-traditional occupations: challenging men. New York (NY): Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brandth B, Follo G, Haugen MS. 2004. Women in forestry: dilemmas of a separate women’s organization. Scand J Forest Res. 19(5):466–472. doi: 10.1080/02827580410019409

- Brandth B, Haugen MS. 2000. From lumberjack to business manager: masculinity in the Norwegian forestry press. J Rural Stud. 16(3):343–355. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(00)00002-4

- Brandth B, Haugen MS. 2005. Doing rural masculinity - from logging to outfield tourism. J Gend Stud. 14(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/0958923042000331452

- Cockburn C. 1991. In the way of women: men’s resistance to sex equality in organizations. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Collinson D, Collinson M. 1989. Sexuality in the workplace: the domination of men’s sexuality. In: Hearn J, editor. The sexuality of organization. London: Sage; p. 91–109.

- Collinson M, Collinson D. 1996. “It’s only dick”: the sexual harassment of women managers in insurance sales. Work Employ Soc. 10(1):29–56. doi: 10.1177/0950017096101002

- Corcione D. 2018. The shitty media men list is the #MeToo of toxic newsrooms: a failure to protect non-male freelance workers. Feminist Media Stud. 18(3):500–502. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2018.1456164

- Coutinho-Sledge P. 2015. Feminized forestry: the promises and pitfalls of change in a masculine organization. Gend Work Organ. 22(4):375–389. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12098

- Denissen AM, Saguy AC. 2014. Gendered homophobia and the contradictions of workplace discrimination for women in the building trades. Gend Soc. 28(3):381–403. doi: 10.1177/0891243213510781

- De Welde K, Stepnick A, Pasque PA, Pasque PA. 2015. Disrupting the culture of silence : confronting gender inequality and making change in higher education. Sterling (Virginia): Stylus Publishing.

- Follo G. 2002. A hero’s journey: young women among males in forestry education. J Rural Stud. 18(3):293–306. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00006-2

- Healy G, Bradley H, Forson C. 2011. Intersectional sensibilities in analysing inequality regimes in public sector organizations. Gend Work Organ. 18(5):467–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00557.x

- Hearn J, Parkin W. 2001. Gender, sexuality and violence in organizations : the unspoken forces of organization violations. London: SAGE.

- Hearn J, Sheppard D, Tancred-Sheriff P, Burrell G. 1989. The sexuality of organization. London: Sage.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. 2005. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ingraham C. 1994. The heterosexual imaginary: feminist sociology and theories of gender. Sociol Theor. 12(2):203–219. doi: 10.2307/201865

- Johansson K, Andersson E, Johansson M, Lidestav G. 2017. The discursive resistance of men to gender equality interventions: negotiating “unjustness” and “unnecessity” in Swedish forestry. Men Masc. (In print).

- Johansson K, Andersson E, Johansson M, Lidestav G. forthcoming. One step forward, two steps back? The gendered conditions of women working in a men-dominated industry aspiring gender equality. In review.

- Johansson M, Ringblom L. 2017. The business case of gender equality in Swedish forestry and mining - restricting or enabling organizational change. Gend Work Organ. 24(6):628–642. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12187

- Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. 2010. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus Horizons. 53(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

- Kensbock S, Bailey J, Jennings G, Patiar A. 2015. Sexual harassment of women working as room attendants within 5-star hotels. Gend Work Organ. 22(1):36–50. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12064

- Kilmartin C. 2014. Counseling men to prevent sexual violence. In: Englar-Carlson M, Evans MP, Duffey T, editors. A counselor’s guide to working with men. Alexandria (USA): John Wiley & Sons; p. 247–262.

- Kilmartin C. 2015. Men’s violence against women: an overview. In: Johnson AJ, editor. Religion and men’s violence against women. New York (NY): Springer New York; p. 3–14.

- Krippendorff K. 2004. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks (Calif.): Sage.

- Langton R. 2009. Sexual solipsism: philosophical essays on pornography and objectification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lidestav G. 2010. In competition with a brother: women’s inheritance positions in contemporary Swedish family forestry. Scand J Forest Res. 25(9):14–24. doi: 10.1080/02827581.2010.506781

- Lidestav G, Andersson E, Lejon SB, Johansson K. 2011. Jämställt arbetsliv i skogssektorn - underlag för åtgärder = [Gender equality in working life of the forest sector - basis for action]. Umeå: Institutionen för skoglig resurshushållning, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet.

- MacKinnon CA. 1979. Sexual harassment of working women : a case of sex discrimination. New Havenn: Yale univ. P.

- Martin PY. 2001. “Mobilizing masculinities”: women’s experiences of men at work. Organization. 8(4):587–618. doi: 10.1177/135050840184003

- McDowell L. 1997. Capital culture: gender at work in the city. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Nussbaum MC. 1995. Objectification. Philos Public Aff. 24(4):249–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x

- Paap K. 2006. Working construction. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press.

- Watts JH. 2007. Porn, pride and pessimism: experiences of women working in professional construction roles. Work Employ Soc. 21(2):299–316. doi: 10.1177/0950017007076641

- Witz A, Halford S, Savage M. 1996. Organized bodies: gender, sexuality and embodiment in contemporary organisations. In: Adkins L, Merchant V, editors. Sexualizing the social: power and the organization of sexuality. London: Macmillan; p. 173–190.

- Wright T. 2008. Lesbian firefighters: shifting the boundaries between “masculinity” and “femininity”. J Lesbian Stud. 12(1):103–114. doi: 10.1300/10894160802174375

- Wright T. 2013. Uncovering sexuality and gender: an intersectional examination of women’s experience in UK construction. Construct Manag Econ. 31(8):832–844. doi: 10.1080/01446193.2013.794297

- Wright T. 2016. Women’s experience of workplace interactions in male-dominated work: the intersections of gender, sexuality and occupational group. Gend Work Organ. 23(3):348–362. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12074

- Zarkov D, Davis K. 2018. Ambiguities and dilemmas around #MeToo: #ForHow long and #WhereTo? Eur J Womens Stud. 25(1):3–9. doi: 10.1177/1350506817749436