To the Editor

The unique ability of thyroid cells to accumulate iodine has been used for diagnosis and treatment of benign and malignant diseases since the 1940s Citation[1], Citation[2]. The use of radioactive iodine in the therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer in Sweden was first published some years later Citation[3]. I would like to present some patients with functioning thyroid cancer treated at Radiumhemmet in Stockholm during the 1950s when I was responsible for the clinical radioiodine treatment at the hospital.

illustrates a 58 year old woman who was operated for a malignant submandibular tumour first considered to be of salivary origin. She received postoperative radiotherapy. One year later she developed a nodule in the right thyroid lobe and her basal metabolism was increased, +50%. She was operated with partial thyroidectomy and histopathology showed a thyroid cancer. Postoperative scanning with 131I identified an uptake in the mediastinum but no activity in the thyroid region. Urinary excretion of 131I was low. Chest radiography showed a metastatic lesion in the pulmonary hilus. The submandibular tumour was reevaluated and considered to represent a metastasis of thyroid cancer. She was treated with 100 mCi 131I, and illustrates the uptake in the mediastinal lesion. At follow-up the mediastinal uptake disappeared and an accumulation in the thyroid region was demonstrated. A second treatment with 131I was given, and 7 months later no uptake could be found in the mediastinum or in the thyroid region. illustrates the patient during the euthyroid, hyperthyroid, and the euthyroid state.

Figure 1. A 58 year old woman with metastatic thyroid cancer. Euthyroid (left panel), hyperthyroid due to functioning mediastinal metastases (middle panel), and euthyroid after thyroidectomy and 131I treatment and on thyroid hormone substitution (right panel).

Figure 2. Profile scanning of 131I uptake showing initial uptake over metastases in the mediastinum. After 131I treatment uptake in the thyroid rest is observed. After retreatment with 131I also the thyroid rest is ablated.

represent a woman who at age 15 had a nodule to the left in the thyroid region. No treatment was given. When she was 67 years she was admitted to the hospital with a 9 cm nodule in the thyroid region and a lesion of similar size to the left in the forehead (). Investigation showed an advanced thyroid cancer with an osseous metastasis in the skull. The uptake of 131I in the lesions is demonstrated in . The patient was operated with thyroidectomy. 131I therapy and thyroid hormone substitution was given and external radiotherapy, 5000 rad, to the lesion in the skull that gradually diminished ().

Figure 5. The patient in , 19 months after thyroidectomy, 131I treatment, external radiotherapy and thyroid hormone substitution.

& represent a woman who had goitre since age 19. At age 38 she had obstructive symptoms and was operated with thyroidectomy. Histopathology showed a thyroid cancer. Four years later she was operated for a subcutaneous lesion on the right forearm, a metastasis of thyroid cancer. Postoperative radiotherapy was given to the operation field. Scintigraphy with 131I showed an accumulation in the thyroid region (, left panel). She was treated with 131I. Ten weeks after the treatment the profile registration shows uptake in cervical and mediastinal lymph nodes metastases (, right panel, ).

Figure 6. Scanning of 131I uptake in a 42 year old woman with thyroid cancer operated with right-sided hemithyroidectomy (left panel). The right panel shows uptake in lymph node metastases on the right side of the neck and in the mediastinum following 131I treatment.

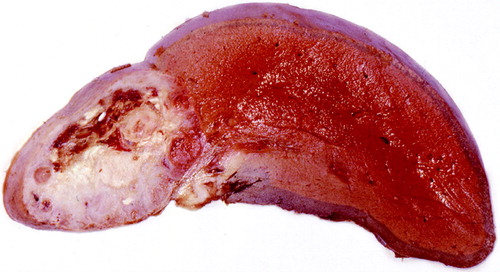

& represent a man operated for a benign goiter at 52 years of age. Nine years later he had a lesion adjacent to the left humerus. A biopsy showed that this was a metastasis from a thyroid cancer that invaded the osseous tissue. He also had bilateral pulmonary lesions and hepatomegaly. The scintigraphy showed an intense uptake of 131I over the liver lesion as well as other metastases in the lungs and the skeleton. He was treated with several doses of 100 mCi 131I. His general condition deteriorated and he had chronic fever, and later he developed tuberculosis. shows the liver metastasis at autopsy.

Figure 8. Whole body scanning of 131I uptake in a 52 year old man with metastatic thyroid cancer. Metastases to the liver, the lungs and the skeleton are demonstrated.

represents the effect of 131I therapy in a woman with a skeletal metastasis of thyroid cancer. At age 13 she was irradiated because of bilateral cervical lymph nodes. When she was 31 years she was operated for a thyroid tumour and within a year she developed a swelling in the skull. X-ray showed an approximately 3 cm large destruction of the bone. She was treated with 50 and later 100 mCi 131I. shows the epilation due to radioactivity and to the right the status when baldness was restituted. The patient died at age 74 due to metastatic colon cancer.

Figure 10. Demonstration of the epilation caused by 131I treatment of a metastasis in the skull (left panel). The right panel shows later regrowth of hair.

represent a 26 year old woman who also had been irradiated for cervical lymph nodes when she was 5 years old. She was operated for a benign goitre at age 24, but within one year she developed a relapse with three palpable lesions in the thyroid region. Reoperation showed malignancy and a total thyroidectomy was performed. Radiotherapy was administered to the operation field. During the following years she had several local relapses and was treated with repetitive irradiations. The patient had pulmonary lesions showing slow progression (). To suppress the pituitary stimulation a hypophysectomy was performed in 1957 and serial measurements of the metastases on chest radiography showed a striking reduction of the size of the pulmonary metastases as a result of this operation ().

Figure 11. Chest radiography showing two pulmonary metastases in a 38 year old woman with thyroid cancer.

Figure 13. Diagram showing the initial very slow progression of two pulmonary metastases and then the effect of hypophysectomy (compare & ).

This handful of patients from the 1950s illustrates the role of radioactive iodine in diagnosis and treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer. Furthermore, two of the patients had been exposed to radiotherapy to the cervical region during childhood, illustrating the etiologic role of ionising radiation in thyroid cancer Citation[4]. The accumulation of radioactive iodine in advanced thyroid cancer offers an option to surgery and other palliative treatments. However, the substitution with thyroid hormone is most crucial. It must also be emphasized that the ability of thyroid cancer cells to accumulate iodine may be lost during tumour progression, a fact that implies the effectiveness of early treatment.

For the arrangement of this symposium and the collection of illustrative cases in this article. I am deeply indebted to associate Professor Torgny Rasmuson.

References

- Seidlin SM, Marinelli LD, Oshry E. Radioactive iodine therapy: Effect on functioning metastases of adenocarcinoma of the thyroid. JAMA 1946; 132: 838–47

- Rawson RW, Rall JE, Peacock W. Limitations and indications in the treatment of cancer of the thyroid with radioactive iodine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1951; 11: 1128–42

- Egmark A, Larsson LG, Liljestrand A, Ragnhult I. Iodine-concentrating thyroid carcinomas; a report of three cases. Acta Radiol 1953; 39: 423–33

- Duffy BJ, Fitzgerald PJ. Cancer of the thyroid in children: A report of 28 cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1950; 10: 1296–308