Abstract

Background: Many patients are diagnosed with an anal cancer in high ages. We here present the outcome after oncological therapy for patients above 80 years compared with younger patients.

Materials and methods: A series of 213 consecutive patients was diagnosed and treated at a single institution from 1984 to 2009. The patients received similar radiation doses but with different techniques, thus progressively sparing more normal tissues. The majority of patients also had simultaneous [5-fluorouracil (5FU) and mitomycin C] or induction chemotherapy (cisplatin and 5FU). The patients were stratified by age above or below 80 years. Despite that the goal was to offer standard chemoradiation treatment to all, the octo- and nonagenarians could not always be given chemotherapy.

Results: In our series 35 of 213 anal cancer patients were above 80 years. After initial therapy similar complete response was observed, 80% above and 87% below 80 years. Local recurrence rate was also similar in both groups, 21% versus 26% (p = .187). Cancer-specific survival and relative survival were significantly lower in patients above 80 years, 60% and 50% versus 83% and 80%, (p = .015 and p = .027), respectively.

Conclusion: Patients older than 80 years develop anal cancer, but more often marginal tumors. Even in the oldest age group half of the patients can tolerate standard treatment by a combination of radiation and chemotherapy, and obtain a relative survival of 50% after five years. Fragile patients not considered candidates for chemoradiation may be offered radiation or resection to control local disease.

Anal cancer is an uncommon cancer in Norway with an annual incidence of about 60 new cases [Citation1]. Before 1983 all early anal cancers were treated by surgery, most often by an abdominoperineal resection (APR), which cured 60% of the resected patients [Citation2,Citation3]. Only unresectable tumors and locoregional recurrences were treated by irradiation, often with substantial side effects. Based on publications by Papillon [Citation4] and Cummings [Citation5] on radiation therapy for localized anal cancer, and Nigro and other groups [Citation6–8] on early use of a combination of radiation and chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and mitomycin C (MMC), we introduced this combination therapy as our standard regimen, instead of surgery in Bergen in 1983. From 2001 to 2007, patients with locally advanced primary tumors (T3 and T4) and/or lymph node metastases were included in the Nordic Anal Cancer Project (NOAC) [Citation9]. The treatment of anal cancer follows internationally accepted guidelines [Citation10,Citation11]. However, the optimal treatment for the patients above the age limits for inclusion in randomized trials, is still not well documented. Despite few studies included patients above 90 and even 100 years of age, a limited number of series have specifically reported on the outcome for patients above 80 years of age [Citation12–21]. In the current study, we analyzed the overall efficacy and feasibility of the combination of radiation and chemotherapy with particular focus on octo- and nonagenarians with anal cancer.

Materials and methods

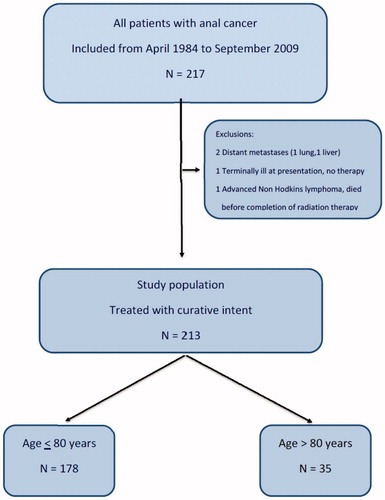

From April 1984 to September 2009, a total of 217 consecutive patients were referred to the Department of Oncology, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen. Our department is the single referral center for patients with anal cancer in Western Norway, serving a population of about one million. Four patients were excluded from the current analysis () and 213 patients with local anal carcinoma treated with curative intent were eligible for analysis. In this cohort we address the outcome in the patients above and below 80 years of age in order to assess whether the oldest patients actually benefit from an active treatment approach.

Tumors mainly localized in the anal canal were classified as anal canal cancers, whereas tumors located on the skin covering an area within 5 cm from the anal verge, were classified as anal margin cancers. All tumors were verified by histopathologic examination. Patient characteristics are presented in with regard to age, below and above 80 years. There was no difference of symptoms between the two age groups (data not shown). There was significantly more anal margin tumors in the oldest age group compared to the younger age group (51% vs. 32%, p = .028). The histological subtypes also varied, i.e. cloacogenic carcinomas were more common in the youngest age group, in contrast to Paget’s disease which was more common after the age of 80 years. All histological groups were treated according to the same guidelines as given below. Adenocarcinomas were considered as rectal cancers and these tumors were therefore not included in this study.

Table 1. Patient characteristics of anal cancer diagnosed 1984–2009, presented by age above or below 80 years.

All patients underwent standard blood tests including liver and kidney function tests, chest X-ray examinations and abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans. Since 1995 chest X-ray examinations were replaced by chest CT, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) became the standard procedure as it better demonstrates the extent of the primary tumor and pelvic lymph nodes. All patients underwent anorectoscopy and palpation by an experienced senior consultant for final classification, together with palpation of lymph nodes in the groins. Fine needle cytology was used where the radiological or clinical assessment of lymph nodes were uncertain. PET scanning was not routinely used in the period the patients were recruited.

For staging we followed the fourth edition of UICC TNM classification from 1987: T1: Primary tumor <2 cm, T2: Primary tumor 2–5 cm, T3: Primary tumor >5 cm, T4: Infiltration of neighboring structures. N0: No lymph nodes, N1: Pararectal lymph nodes, N2: Unilateral internal iliac nodes and/or unilateral inguinal nodes, N3: Metastasis in perirectal and inguinal nodes, and/or bilateral internal iliacal and/or inguinal nodes. M0: No distant metastasis, M1: Distant metastasis(es) [Citation22]. There were fewer stage T1 tumors and less T4 tumors in the oldest age group (p = .013; ).

Radiotherapy

Initially, we used a three-field technique according to individual two-dimensional treatment plans, consisting of one anterior field and two oblique dorsal wedged fields with the patient in supine position. For morphologically verified inguinal node metastases, electron fields against both inguinal regions were added. Since 1987 we changed to two opposing anterior and posterior fields including the true pelvis with a 1 cm margin to the lateral pelvic bone brim. The fields were widened to include the inguinal regions when lymph node metastases were present. The upper limit was the sacral promontory and lower edge at least 3 cm below the anus or tumor if it was visible. By both techniques a split course regimen was used: first a series of 40 Gy in 20 fractions over four weeks were given. After three weeks’ rest, an additional dose of 16 Gy in 8 fractions was added by a perineal electron field directed 10–15 degrees dorsal with the patient in lithotomy position. Typically, this field measured 9 × 9 cm and was given by 16–19 MeV electrons. One of the old patients had all radiation by an electron field to 60 Gy due to presumed reduced radiation tolerance. Mean actual given doses for all patients treated with this technique was 55.6 Gy (range 40–73 Gy). Since 1995 we used 3D dose planning based on CT simulations where the primary tumor was covered by a margin of at least 2 cm to a dose of 54–60 Gy together with a dose of 42–46 Gy to uninvolved regional nodes, without scheduled gaps. The upper border was set at the lower end of the iliosacral joints or at the sacral promontory if the tumor extended above the dentate line. Since 2008 we administered most radiation therapy using intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) treatment plans. Despite different planning procedures, the primary tumor and the lymph nodes received similar doses through the whole period, while uninvolved tissues were progressively spared from unnecessary radiation exposure. Both young and elderly patients were treated with the same techniques.

Chemotherapy

The chemotherapy regimen (FuMi) was administered as a continuous infusion of 5FU (750 mg/m2/day Day 1–5 or 1000 mg/m2/day Day 1–4) in combination with a 30 min infusion of MMC (15 mg/m2 in the first period, in 1987 reduced to 10 mg/m2 due to bone marrow toxicity, most often thrombocytopenia; ). The chemotherapy started Day 1 or 2 of the radiation therapy. Most patients had one course of chemotherapy, but patients with advanced T3 and T4 tumors had a second FuMi course the fifth week of radiation therapy. Patients considered ineligible for chemotherapy had radiation alone. As part of the NOAC project patients under 80 years, had primary chemotherapy (neoadjuvant) with two courses of cisplatin and 5FU (CiFu) consisting of 5FU (1000 mg/m2 Day 1–4) combined with cisplatin (100–75 mg/m2) infusion over four hours Day 1 [Citation9]. A third course of the same regimen, but with reduced cisplatin doses (60–75 mg/m2), was given the first week of radiation therapy.

Table 2. Primary treatment for anal cancer patients according to age above and below 80 years. CiFU: cisplatin and fluorouracil, given as two initial courses and one course the first week of radiation therapy; FuMi: fluorouracil and mitomycin C administered concurrent with radiation; RT: radiation therapy.

Surgery

All anal cancers had local resections or APR for cure before 1983. Some patients followed this procedure the first years of this study, mainly at local hospitals: in 20 patients (9%) gross tumor had been resected before admission to Haukeland University Hospital, and 10 of these were accepted as adequately treated by the initial surgical procedure. In the current series local excision of well differentiated squamous cell carcinomas at the anal margin with a diameter of less than 2 cm and tumor-free margins, was considered as radical surgery. All tumors larger than 2 cm, or anal margin cancers less than 2 cm with moderate or low differentiation, were treated by radiation with or without chemotherapy. APR was only used for persisting tumors after radiation alone or combined with chemotherapy and for treatment of persisting necrotic ulcers in the tumor bed.

Follow-up

Most patients were followed at the Outpatient Clinic, Department of Oncology, Haukeland University Hospital, by an experienced oncologist, for a minimum of several months until a complete clinical response was ascertained. Some patients were then followed at the local hospital by a colorectal surgeon who regularly sent follow-up reports. If there was a persistent tumor, confirmed by biopsy, an APR was performed if feasible. Regular control was scheduled every six months for five years with clinical examination, rectoscopy if feasible, blood counts, chest X-ray and ultrasound of the abdomen with additional CT or MR examination when clinically indicated.

Statistics

The data were analyzed by the IBM SPSS 22 package (IBM SPSS Statistics Inc., Chicago, IL). Survival estimates were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and significance assessed by the log-rank test. The results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Differences with p < .05 were considered statistically significant by two-sided tests. Relative survival for anal cancer patients were calculated using flexible parametric survival models in STATA [Citation23]. A sparse model with only sex and year of diagnosis as explanatory variables was used. In the other model, age above/below 80 years was added as an explanatory variable. A standard likelihood ratio test of the two models was performed to assess whether relative survival differed between patients above and below 80 years. Toxicity was scored according Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events v3.0 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf).

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee West, and the study therefore complies with the official legal regulations in Norway.

Results

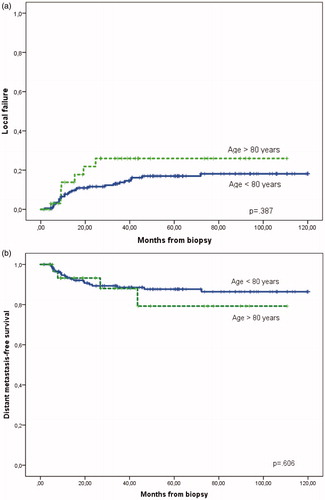

A total of 213 patients were treated with curative intent in the period studied. There were 35 patients above 80 years at presentation. In total 133 patients under 80 years, and 19 above 80 years had chemotherapy (; p < .05). Thus, chemotherapy was significantly less used in the oldest age group. The primary treatment resulted in similar rate of complete response (CR) regardless of age: 155 CR (87%) under 80 years versus 28 CR (80%) above 80 years (p = .279), assessed clinically 1–3 months after treatment. For all patients the five-year disease-free survival (DFS) was 71% (95% CI 64–77%), with more than 90% of the recurrences seen within the first three years. DFS at five-year was 73% (95% CI 66–80%) for the younger group and 59% (95% CI 39–79%) in the eldest group, p = .187. There was no difference in local failure rate (recurrences with or without distant metastases or direct progression) below and above 80 years, 21% (95% CI 14–27%) and 26% (95% CI 9–43%), respectively (p = .387; . Direct progression during and immediately after treatment was observed in six patients in the younger group compared to only one in the eldest group. Distant metastasis-free survival was also similar, 88% (95% CI 82–93%) and 79% (95% CI 59–99%), p = .606 (.

Figure 2. (a) Local failures, local recurrence and direct progression after primary treatment for anal cancer. (b) Distant metastases after primary treatment for anal cancer. Both figures show separate data for patients above and below 80 years. No significant difference.

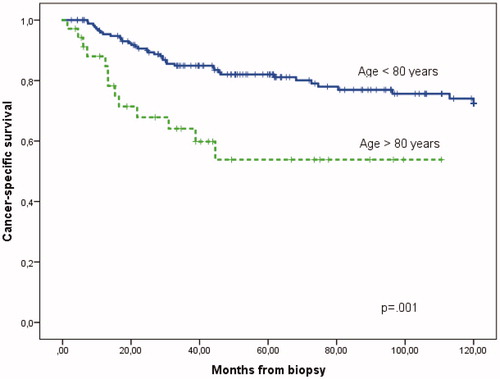

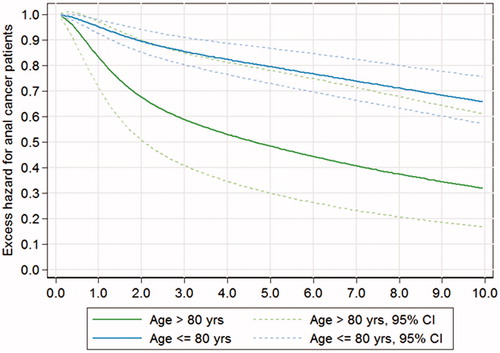

The five-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) for patients less than 80 years was 83% (95% CI 77–89%) in contrast to the oldest group, 60% (95% CI 40–80%), p = .015 (). When including death of complications caused by the primary or salvage therapy (chemotherapy and surgery) the CSS actually was 82% (95% CI 76–88%) compared to 54% (95% CI 34–73%), p = 0.001. Mortality by other causes was significantly higher in the oldest group, 34% (95% CI 12–56%) versus 11% (95% CI 6–16%), p < .001; largely due to cardiovascular diseases. The overall five-year survival observed in the two groups was 73% (95% CI 64–80%) and 36% (95% CI 18–53%), p < .001, respectively. The median survival time in the oldest group was 39 months. As a comparison, the five-year relative survival for the group above 80 years was 50%, thus significantly reduced compared to 80% for patients <80 years (p = .0271), assessed by the likelihood ratio test (). Thus, the mortality that can be attributed to the diagnosis and treatment of anal cancer is higher in the oldest age group.

Figure 3. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) including death of anal cancer and treatment complications above and below 80 years (p = 0.001).

Figure 4. Relative survival for patients with anal carcinoma above or below 80 years with 95% confidence intervals. p = 0.0271 assessed by the likelihood ratio test.

Toxicity

Acute side effects were only prospectively scored during the first period for 106 patients. The respective distribution in the two groups were: Grade 0: 8 and 0, Grade 1: 18 and 4, Grade 2: 35 and 10, Grade 3: 31 and 3, Grade 4: 7 and 2 in patients below and above 80 years, respectively. Thus 36% in the younger group and 26% in the oldest group exhibited Grade 3 and 4 acute toxicity. When only the patients treated by the FuMi regimen were assessed, there was no difference in reported acute toxicity rate. However, late (>3 months after therapy) side effects Grade 3–4 occurred in 26 of 128 patients (15%) in the younger group against none in the eldest group (p = .022). In the eldest group one woman died of cardiac failure and pneumonia after 26 Gy radiation combined with the FuMi regimen, while two others died of complications during treatment for recurrence. Thus, the mortality due to primary treatment was acceptable in this series as only one 84-year-old female with serious comorbidity died during treatment as a consequence of the primary treatment.

Anal function

One of the main goals of using radiation combined with chemotherapy is preservation of the control of bowel movements. In the elderly group three patients ended up with a colostomy, one due to residual tumor after chemoradiation and two due to recurrences. In the younger group a total of 41 patients had a colostomy, eight of them before tumor treatment due to obstructing or fistulating tumors, eight due to residual disease, 13 due to recurrences, 11 for symptom palliation of complications (ulcerations, fistulas or necrosis) and one because of a secondary rectal cancer. For all the patients in this study the five-year colostomy-free survival was 82% (95% CI 77–88%). In the younger group the five-year colostomy-free survival was 80% (95% CI 74–86%) versus 91% (95% CI 80–100%) in the group over 80 years of age (p = .248; Supplementary Figure 1). This non-significant difference might be explained by the less intense treatment given to the elderly patients. In addition to patients having colostomies, seven patients were reported having various degrees of fecal incontinence after treatment, six of these were in the younger group.

Discussion

DFS, CSS and overall survival rates in all patients is comparable with other recently published series [Citation1,Citation9,Citation24,Citation25]. We observed similar CR, local failures and distant metastases in both age groups. Despite the initial good responses also reflected in similar DFS in the oldest group, we observed statistically significant poorer CSS in the oldest group. One reason for this discrepancy could be that older patients and patients with other debilitating comorbidities does not undergo scheduled controls and their symptoms may be masked by other clinical symptoms. The younger patients could probably tolerate more active second line treatment, i.e. major surgical resections as reflected in a significant better CSS in the younger group. CSS relies on the quality of the coding of the cause of death, and has been found to be less reliable for rare cancers and for patients aged 85 and above [Citation26]. Relative survival is thus a more robust and reliable measure of the mortality attributable to the anal cancer disease.

The observed difference in OS is as expected for the age group under consideration as the mean age in the eldest group was 85 years. In Norway, the expected remaining life time for an 80-year-old woman is now 6.4 years and for men 5.9 years, which is further expected to increase by about three and two years, respectively (Statistics Norway). Therefore, the treatment for patients above 80 years aims at control of the cancer for many years. We should not forget that without treatment anal cancer is a cumbersome disease leading to death within few months.

Our colostomy-free survival rate is well above a recent published study from Denmark [Citation27]. The acute toxicity data recorded reflect that the larger fields used in the first time period, probably was more important for development of acute dermatitis and diarrhea during treatment, as we now see these reactions mainly in the group with the largest tumors who received the largest treatment volumes to cover the tumor. In our series more intense chemotherapy regimens were used in the younger age group (), which can explain why we did not observe more late toxicity in the eldest group. This apparent difference probably reflects the more intense treatment policy in the younger age groups, but also earlier deaths due to other diseases in the eldest group, shifting the focus away from symptoms related to the initially given treatment.

For assessment of presumed treatment tolerance, we clinically assessed the classic prognostic factors such as patients’ general performance status, advanced disease and judged the comorbidity, as most important for selection of therapy [Citation28]. We did not use more complex gradings like comprehensive geriatric assessment scales [Citation29]. These tools have not yet demonstrated sufficient consistency to accurate predict treatment tolerance [Citation30]. Hopefully, such instruments can be further developed in the future.

Current advances in radiation techniques (IMRT, including volumetric arc techniques, tomotherapy and protons) aim at reducing exposure of normal tissues and may therefore reduce side effects and improve the tolerance for radiation, allowing concomitant chemotherapy for more patients in the older age group [Citation31–36]. When administering chemotherapy, one must be aware of the risk of severe diarrhea, leucopenia and septicemia which can be fatal in some patients. We observed that patients between 75 and 80 years did not differ from younger ones concerning tumor response and side effects. In the sparse series on elderly anal cancer patients some set the lower age to 70 years [Citation12,Citation18,Citation20], 75 years [Citation13,Citation17,Citation21] and 77 years [Citation14]. Which age that needs specific attention in elderly anal cancer patients who need specific treatment adjustments is not yet clearly defined. Our experience indicates that we should judge the patient as candidates for active chemoradiation therapy as long as the general health is sufficient to cooperate in a satisfactory way and as long as there is no serious comorbidity that will seriously interact with standard therapy, also above 80 years.

The strength of the current study is that the patients were recruited from a geographical area and treated and assessed by a single institution and one senior oncologist, but our study is limited by being a retrospective study recruiting few patients from a long time period with changes in diagnostic and treatment procedures.

Conclusion

Patients older than 80 years develop anal cancer, but with more marginal tumors than in younger patients. Even in the oldest age group more than half of the patients can tolerate standard treatment by a combination of radiation and the FuMi regimen. Patients not considered candidates for chemoradiation may be offered radiation or resections to control the disease, especially in fragile patients which may not tolerate chemotherapy.

Fig_1_Suppl.1_298_.pdf

Download PDF (185.3 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Bentzen AG, Guren MG, Wanderas EH, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of anal carcinoma: survival and recurrence in an unselected national cohort. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;83:e173–80.

- Clark MA, Hartley A, Geh JI. Cancer of the anal canal. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:149–57.

- Lund JA, Wibe A, Sundstrom SH, et al. Anal carcinoma in mid-Norway 1970-2000. Acta Oncol 2007;46:1019–26.

- Papillon J, Mayer M, Montbarbon JF, et al. A new approach to the management of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer 1983;51:1830–7.

- Cummings BJ. The place of radiation therapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer Treat Rev 1982;9:125–47.

- Cummings BJ. Carcinoma of the anal canal–radiation or radiation plus chemotherapy? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1983;9:1417–18.

- Flam MS, John M, Lovalvo LJ, et al. Definitive nonsurgical therapy of epithelial malignancies of the anal canal. A report of 12 cases. Cancer 1983;51:1378–87.

- Nigro ND, Seydel HG, Considine B, et al. Combined preoperative radiation and chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Cancer 1983;51:1826–9.

- Leon O, Guren M, Hagberg O, et al. Anal carcinoma: survival and recurrence in a large cohort of patients treated according to Nordic guidelines. Radiother Oncol 2014;113:352–8.

- Benson AB, 3rd., Arnoletti JP, Bekaii-Saab T, et al. Anal carcinoma, Version 2.2012: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:449–54.

- Glynne-Jones R, Northover JM, Cervantes A. Anal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21 Suppl 5:v87–92.

- Lestrade L, De Bari B, Montbarbon X, et al. Radiochemotherapy and brachytherapy could be the standard treatment for anal canal cancer in elderly patients? A retrospective single-center analysis. Med Oncol 2013;30:402.

- Allal AS, Obradovic M, Laurencet F, et al. Treatment of anal carcinoma in the elderly: feasibility and outcome of radical radiotherapy with or without concomitant chemotherapy. Cancer 1999;85:26–31.

- Charnley N, Choudhury A, Chesser P, et al. Effective treatment of anal cancer in the elderly with low-dose chemoradiotherapy. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1221–5.

- Chauveinc L, Buthaud X, Falcou MC, et al. Anal canal cancer treatment: practical limitations of routine prescription of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Br J Cancer 2003;89:2057–61.

- Claren A, Doyen J, Falk AT, et al. Results of age-dependent anal canal cancer treatment: a single centre retrospective study. Dig Liver Dis 2014;46:460–4.

- De Bari B, Lestrade L, Chekrine T, et al. Should the treatment of anal carcinoma be adapted in the elderly? A retrospective analysis of acute toxicities in a French center and a review of the literature. Cancer Radiother 2012;16:52–7.

- Fallai C, Cerrotta A, Valvo F, et al. Anal carcinoma of the elderly treated with radiotherapy alone or with concomitant radio-chemotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;61:261–8.

- Foo M, Link E, Leong T, et al. Impact of advancing age on treatment and outcomes in anal cancer. Acta Oncol 2014;53:909–16.

- Saarilahti K, Arponen P, Vaalavirta L, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of anal cancer is feasible in elderly patients: treatment results of mitomycin-5-FU combined with radiotherapy at Helsinki University Central Hospital 1992-2003. Acta Oncol 2006;45:736–42.

- Valentini V, Morganti AG, Luzi S, et al. Is chemoradiation feasible in elderly patients? A study of 17 patients with anorectal carcinoma. Cancer 1997;80:1387–92.

- Hermanek P, Sobin LH. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 4th ed. Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag; 1987.

- Lambert PC, Royston P. Further development of flexible parametric models for survival analysis. Stata J 2009;9:265–90.

- Gunderson LL, Winter KA, Ajani JA, et al. Long-term update of US GI intergroup RTOG 98-11 phase III trial for anal carcinoma: survival, relapse, and colostomy failure with concurrent chemoradiation involving fluorouracil/mitomycin versus fluorouracil/cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4344–51.

- Peiffert D, Tournier-Rangeard L, Gerard JP, et al. Induction chemotherapy and dose intensification of the radiation boost in locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: final analysis of the randomized UNICANCER ACCORD 03 trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1941–8.

- Skyrud KD, Bray F, Moller B. A comparison of relative and cause-specific survival by cancer site, age and time since diagnosis. Int J Cancer 2014;135:196–203.

- Sunesen KG, Norgaard M, Lundby L, et al. Cause-specific colostomy rates after radiotherapy for anal cancer: a Danish multicentre cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3535–40.

- Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, et al. Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1829–34.

- Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, et al. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e437–44.

- Hamaker ME, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, et al. The value of geriatric assessments in predicting treatment tolerance and all-cause mortality in older patients with cancer. Oncologist 2012;17:1439–49.

- Julie DR, Goodman KA. Advances in the management of anal cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 2016;18:20.

- Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderås EH, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncol 2013;52:736–44.

- Julie KA, Oh JH, Apte AP, et al. Predictors of acute toxiciries during definitive chemoradiation using intensity-modulated radiotherapy for anal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol 2016;55:208–16.

- De Bari B, Jumeau R, Bouchaab H, et al. Efficacy and safety of helical tomotherapy with daily image guidance in anal canal cancer patients. Acta Oncol 2016;55:767–73.

- Tomasoa NB, Meulendijks D, Nijkamp J, et al. Clinical outcome in patients treated with simultaneous integrated boost-intensity modulated radiation therapy (SIB-IMRT) with and without concurrent chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Acta Oncol 2016;55:760–6.

- Ojerholm E, Kirk ML, Thompson RF, et al. Pencil-beam scanning proton therapy for anal cancer: a dosimetric comparison with intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Acta Oncol 2015;54:1209–17.