To the Editor,

The oral fluoropyrimidine capecitabine is widely used in cancer therapy for solid tumours. It is often preferred over intravenous 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) due to its patient convenience and superior tolerability profile [Citation1,2]. However, the incidence of adverse events remains substantial, with hand-foot syndrome (HFS) as the most commonly observed toxicity. HFS, observed in up to 77% of patients in clinical trials [Citation3], is characterised by erythema, dysesthesia, desquamation, blistering and pain of the palms and soles of feet. The presence of these symptoms may impair quality of life and, in case of dose delays and reductions, may compromise efficacy.

S-1 is a fourth-generation oral fluoropyrimidine that combines the 5-FU prodrug tegafur with two modulators, oteracil and gimeracil. Oteracil inhibits 5-FU phosphorylation in the digestive tract and thereby may lower gastrointestinal toxicity. Gimeracil inhibits 5-FU degradation in order to obtain high levels of 5-FU in serum and tumour tissue [Citation4]. This inhibition subsequently lowers the concentration of the 5-FU catabolites that are thought to elicit HFS [Citation5].

S-1 has been studied extensively in Asian populations and has shown non-inferior efficacy results in different treatment regimens compared to capecitabine and intravenous 5-FU [Citation6–10]. The SALTO study, a randomised phase 3 study in a Western population, showed a significant lower incidence of HFS upon the use of S-1 compared to capecitabine (45% vs 71%, p < 0.001), with comparable efficacy results in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer [Citation11].

These data suggest that S-1 is a useful alternative to capecitabine. However, there are no data in patients on the tolerability of S-1 after HFS-related discontinuation of capecitabine. Therefore, we conducted this retrospective study in order to determine the tolerability of S-1 after HFS-related discontinuation of capecitabine, with special interest in HFS.

Patients and methods

Patients in The Netherlands and Denmark with any type of cancer who switched from capecitabine to S-1 (given as single agents or in combination schedules) because of HFS between June 2012 and September 2016 were reviewed. Baseline clinicopathological factors including (but not limited to) sex, age, number of cycles of capecitabine administered, reason for switch to S-1, dose and schedule of S-1, number of cycles administered, dose delays, dose reductions, toxicities and reasons for discontinuation were collected in case report forms.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of any grade HFS upon treatment switch to S-1. Secondary endpoints were the incidence of grade 3 HFS, other S-1-related adverse events and S-1 dose reductions. The severity of HFS was scored at the end of each cycle by the local investigators according to normal practice in all centres. When a decrease of HFS-related symptoms during treatment with S-1 was observed, the lowest overall grade of HFS was used. S-1-related HFS was compared to the maximum grade of previously capecitabine-induced HFS. All toxicities were scored according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 4.0.

Patients who completed at least one cycle of S-1 were included in the analyses on the incidence of any grade and grade 3 HFS. Patients who received at least one dose of S-1 were included in the analysis on other S-1-related adverse events.

Results

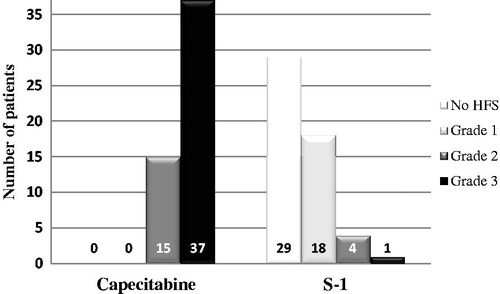

A total of 52 patients from 6 centres were identified. Baseline characteristics are shown in . The maximum grade of capecitabine-induced HFS was grade 2 in 15 patients (29%) and grade 3 in 37 patients (71%), which was scored after the last cycle of capecitabine-containing treatment in all patients.

Tabel 1. Baseline characteristics of patients.

Several S-1 treatment regimens were used (). A total of 49 patients (94%) started S-1 treatment at a full dose of 30 mg/m2 bid for monochemotherapy or 25 mg/m2 for combination treatment. At the time of this analysis, all 52 patients completed at least one cycle of S-1 with a median number of 5 cycles (range 1–13). A total of 49 patients (94%) experienced a lower grade of HFS upon treatment with S-1 compared to the capecitabine-induced grade of HFS, with 29 patients (56%) experiencing a complete resolution of HFS-related symptoms (). S-1 was initiated in 33 patients (63%) without waiting for a decrease in HFS-related symptoms, i.e., when the maximum grade of capecitabine-induced HFS was still present. In 28 of these patients (85%), a reduction of symptoms was obtained within two cycles of S-1. Three patients (12%) experienced ongoing grade 2 or 3 HFS, which was one of the reasons to discontinue treatment after one cycle in two of these patients. Upon switch to S-1, the overall incidence of any grade HFS was 44% (23 patients) and of grade 3 HFS 2% (one patient).

Figure 1. Distribution of hand-foot syndrome before and after switch from capecitabine to S-1. Legend Figure 1: S-1 was initiated in 33 patients (63%) without waiting for a decrease in HFS-related symptoms, i.e., when the maximum grade of capecitabine-induced HFS was still present.

Tabel 2. Characteristics of S-1 treatment.

As to other S-1-related adverse events, diarrhoea and fatigue were the most commonly observed toxicities, occurring in 15 (29%) and 20 (38%) patients, respectively. No significant differences were observed between capecitabine and S-1 in the incidence of these toxicities (Supplementary Table S1). No grade 4 or 5 adverse events were reported. Four patients discontinued treatment due to S-1-related toxicities. S-1 dose reductions and dose delays were applied in 11 (21%) and 8 patients (15%), respectively.

Discussion

Our data show that the great majority of patients (94%) who discontinued capecitabine due to HFS and subsequently switched to S-1 experienced a decrease or even a complete resolution of HFS-related symptoms, which allowed for the continuation of fluoropyrimidine treatment with S-1 at full dose. Although the number of patients in our analysis is limited, our findings strongly suggest that S-1 is a feasible and useful alternative in patients who do not tolerate capecitabine due to HFS-related symptoms.

The majority of patients started treatment with S-1 while the maximum grade of capecitabine-induced HFS was still present. Although a reduction of symptoms was observed in most patients within two cycles, three of these patients (9%) experienced ongoing HFS, which resulted in the discontinuation of S-1 in two patients who were therefore considered as S-1 failures. However, since capecitabine-induced HFS may persist for a prolonged period of weeks [Citation12], it cannot be excluded that S-1 would have been tolerated after HFS-related symptoms had decreased. Therefore, if clinically feasible, it may be preferred to initiate S-1 after a decrease of HFS to grade 1 or less.

Our data suggest that S-1 can be administered at the full recommended dose in this setting. Reasons for S-1 dose modifications mainly concerned gastrointestinal toxicities, but these were generally limited to grade 1–2. Importantly, we did not observe a sudden increase of adverse events after the switch to S-1 compared to previously observed toxicities. Diarrhoea has been identified as the S-1 dose limiting toxicity in Western patients [Citation13,14], and was also the most commonly observed adverse event upon treatment with S-1 in the SALTO study (Kwakman et al. manuscript submitted; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01918852).

Patients in our analysis were treated in a 3-weekly (S-1 on day 1–14) and 4-weekly schedule (S-1 on day 1-21). The 4-weekly schedule with S-1 at a dose of 25 mg/m2 bid in combination with cisplatin in the first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer was shown effective and tolerable in the FLAGS trial [Citation7]. S-1 monotherapy in a 3-weekly schedule proved feasible at a dose of 30 mg/m2 bid [Citation13]. The tolerability and efficacy of this latter regimen was confirmed in the SALTO study [Citation11] and should be considered standard in Western patients for S-1 monochemotherapy. The optimal dose of S-1 in combination with other chemotherapeutics has not been firmly established. The maximum tolerated dose of S-1 in combination with oxaliplatin in a Western population was observed at 25 mg/m2 bid and is currently recommended [Citation15]. The feasibility of this regimen is under investigation in a prospective trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02347904).

The design of our study does not allow assessing the efficacy of the substitution of capecitabine by S-1. However, the comparable outcome on survival in previous trials in gastrointestinal cancers does not raise concerns on this topic [Citation6–10]. Previous data from several studies suggest that dose delays and dose reductions of capecitabine do not significantly compromise efficacy outcomes [Citation2,Citation16]. Interestingly, a post hoc analysis of data from the X-ACT trial demonstrated that the occurrence of capecitabine-induced HFS in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer had a positive correlation with the 5-year disease-free and overall survival [Citation16]. These findings may imply that patients whose tumours are sensitive to capecitabine are inherently susceptible to its toxicities. For this reason, when HFS occurs upon treatment with capecitabine, a single dose reduction of capecitabine may be an option prior to a switch to S-1.

We were aware that our study could have the limitation that the severity of HFS had not been documented in sufficient detail by local physicians to allow a translation into objective toxicity grades according to NCI CTC. However, HFS was generally well documented and graded in the patients charts, and we are therefore confident that our data reliably reflect the observed severity of HFS in these patients.

In conclusion, our data show that S-1 should be considered as a treatment alternative in patients who do not tolerate capecitabine because of HFS-related symptoms. When grade 2–3 HFS occurs upon treatment with capecitabine, we recommend to switch treatment to S-1 either immediately or when grade 2–3 HFS persists after an initial dose reduction of capecitabine. In patients in whom dose-intensity is less relevant (i.e., who are treated with palliative intent), it is probably preferred to delay treatment with S-1 until HFS has decreased to grade ≤1.

IONC_1278459_supplemental.docx

Download MS Word (14.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Martijn Lolkema for providing access to the data of one patient.

Disclosure statement

CJAP has an advisory role for Servier and Nordic Pharma. PP has an advisory role for or has received funding from Lilly, Roche, Merck-Serono, Amgen, Celgene, Taiho, Servier and Nordic Pharma. JJMK has received an honorarium by Nordic Pharma. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Twelves C, Gollins S, Samuel L, et al. A randomised cross-over trial comparing patient preference for oral capecitabine and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin regimens in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:239–245.

- Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, et al. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:566–575.

- Tebbutt NC, Wilson K, Gebski VJ, et al. Capecitabine, bevacizumab, and mitomycin in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Randomized Phase III MAX Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3191–3198.

- Shirasaka T, Shimamato Y, Ohshimo H, et al. Development of a novel form of an oral 5-fluorouracil derivative (S-1) directed to the potentiation of the tumor selective cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil by two biochemical modulators. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:548–557.

- Yen-Revollo JL, Goldberg RM, McLeod HL. Can inhibiting dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase limit hand-foot syndrome caused by fluoropyrimidines? Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8–13.

- Muro K, Boku N, Sugihara K, et al. Irinotecan plus S-1 (IRIS) versus fluorouracil and folinic acid plus irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as second-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase 2/3 non-inferiority study (FIRIS Study) Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:853–860.

- Ajani JA, Buyse M, Lichinitser M, et al. Combination of cisplatin/S-1 in the treatment of patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: results of noninferiority and safety analyses compared with cisplatin/5-fluorouracil in the First-Line Advanced Gastric Cancer Study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3616–3624.

- Hong YS, Park YS, Lee JW, et al. S-1 plus oxaliplatin versus capecitabine plus oxaliplatin for first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomised, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1125–1132.

- Yamada Y, Takahari D, Matsumoto H, et al. Leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin plus bevacizumab versus S-1 and oxaliplatin plus bevacizumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (SOFT): an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1278–1286.

- Kwakman JJ, Punt CJ. Oral drugs in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17:1351–1361.

- Punt CJ, Simkens LH, Van Rooijen JM, et al. Randomized phase 3 study of S-1 versus capecitabine in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): the SALTO study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:(suppl; abstr 3640).

- Abushullaih S, Saad ED, Munsell M, et al. Incidence and severity of hand-foot syndrome in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: a single-institution experience. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:3–10.

- Zhu AX, Clark JW, Ryan DP, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of S-1 administered for 14 days in a 21-day cycle in patients with advanced upper gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:285–293.

- van Groeningen CJ, Peters FJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of oral S-1 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2772–2779.

- Chung KY, Saito K, Zergebel C, et al. Phase I study of two schedules of oral S-1 in combination with fixed doses of oxaliplatin and bevacizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Oncology. 2011;81:65–72.

- Twelves C, Scheithauer W, McKendrick J, et al. Capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results from the X-ACT trial with analysis by age and preliminary evidence of a pharmacodynamic marker of efficacy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1190–1197.