Abstract

Background: Radical cystectomy (RC) and radiochemotherapy (RCT) are curative options for muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC). Optimal treatment strategy remains unclear in elderly patients.

Material and methods: Patients aged 80 years old and above with T2-T4aN0-2M0-Mx MIBC were identified in the Retrospective International Study of Cancers of the Urothelial Tract (RISC) database. Patients treated with RC were compared with those treated with RCT. The impact of surgery on overall survival (OS) was assessed using a Cox proportional hazard model. Progression included locoregional and metastatic relapse and was considered a time-dependent variable.

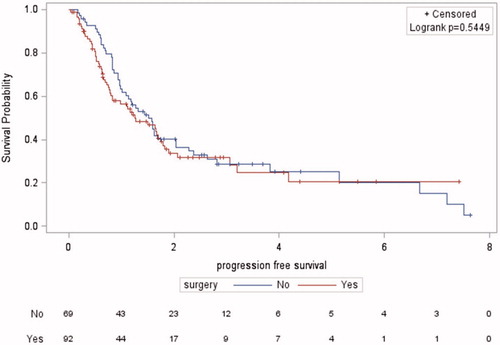

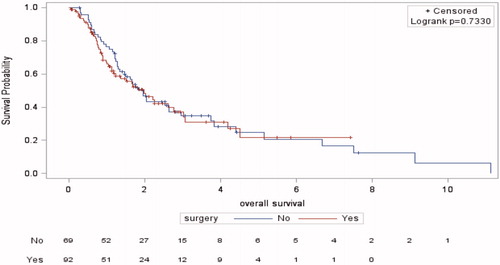

Results: Between 1988 and 2015, 92 patients underwent RC and 72 patients had RCT. Median age was 82.5 years (range 80–100) and median follow-up was 2.90 years (range 0.04–11.10). Median OS was 1.99 years (95%CI 1.17–2.76) after RC and 1.97 years (95%CI 1.35–2.64) after RCT (p = .73). Median progression-free survival (PFS) after RC and RCT were 1.25 years (95%CI 0.80–1.75) and 1.52 years (95%CI 1.01–2.04), respectively (p = .54). In multivariate analyses, only disease progression was significantly associated with worse OS (HR = 10.27 (95%CI 6.63–15.91), p < .0001). Treatment modality was not a prognostic factor.

Conclusions: RCT offers survival rates comparable to those observed with RC for patients aged ≥80 years.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the ninth most common cancer worldwide, with 430,000 new cases in 2012. Northern America and Europe have among the highest incidences in the world with age-standardized rates of 11.6% and 9.6%, respectively [Citation1]. The standard of care in non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy (RC) with extended pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) in fit patients [Citation2]. In a contemporary series reported by Hautmann et al., patients undergoing RC had 10-year recurrence-free and overall survival (OS) of 65.5% and 44.3%, respectively [Citation3]. However, surgery is associated with perioperative mortality and complications, impaired quality of life related to urinary diversion, and extended hospital stays even in patients operated on by high-volume surgeons [Citation4–6]. As the incidence of MIBC increases with age and life expectancy is increasing, more cases will be diagnosed in the elderly. In fact, the median age at diagnosis is 73 years and about 45% of patients are 75 years old or more [Citation7]. Therefore, physicians might be confronted with age-related comorbidities such as renal function impairment, and cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, which can affect treatment choices and outcomes. Multimodality treatment (MMT) could be offered as an alternative in selected, well-informed and compliant patients, especially those for whom cystectomy is not an option [Citation2]. It consists of maximal transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT), followed by radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy (RCT), and limits salvage RC to non-responder tumors or muscle-invasive recurrences. Although no randomized comparisons between cystectomy and MMT exist, data suggest that MMT may yield favorable results in appropriately selected patients [Citation8–10]. In elderly patients, optimal management remains controversial. In this retrospective study, we compared survival outcomes in patients aged 80 years old or more with MIBC treated with concurrent radiochemotherapy (RCT) or RC.

Material and methods

Study population

Patients with T2-T4aN0-2M0-Mx MIBC treated with curative intent between 1988 and 2015 were identified using the Retrospective International Study of Cancers of the Urothelial Tract (RISC) database. RISC is a population-based, retrospective study that includes consecutive urothelial cancer cases from 28 international centers [Citation11]. Only patients aged 80 years old and above with MIBC diagnosed after TURBT were selected from the database. The surgery cohort included patients from the RISC database who received RC. Patients were excluded if they were treated with partial cystectomy or if it was unknown if they received surgery or RCT as the primary treatment. Radiochemotherapy was offered if there were medical and/or surgical contra-indications for cystectomy or when patients rejected surgery. Patients were excluded if they had palliative irradiation, hypofractionated irradiation or radiotherapy without chemotherapy. The patients’ medical records were retrospectively reviewed. Data were collected regarding their gender, age at diagnosis, non-adjusted for age Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), T-stage and N-stage and recurrence. TNM staging was based on the pretreatment computed tomography in both groups. Data regarding complications and prognostic factors were not available, particularly histological tumor grade, tumor size and number, hydronephrosis, and carcinoma in situ.

The RISC database was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Mount Sinaï school of medicine and the design of this study was approved by the RISC consortium.

Statistical analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation to disease progression (locoregional and/or metastatic) or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the time from treatment initiation to death from any cause. The survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the prognostic impact of surgery on OS. Variables included in the univariate analysis were: gender, age at diagnosis (dichotomized using median, ≥83 years versus < 83), non-adjusted CCI (0–1–2 versus ≥3), T stage (T2–3 versus T4), N stage (N0 − Nx versus N+), progression (considered as a time depending variable) and treatment modality (surgery versus RCT). All variables with a p value of .15 or less were included in the multivariate model, adjusted for treatment modality, age, gender, T stage and N stage. Correlation between variables was tested. p Values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All p values were two-sided.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

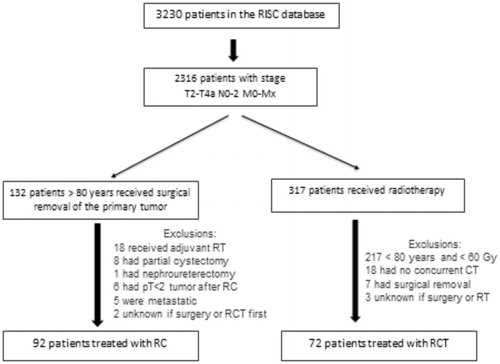

Between 1988 and 2015, 164 patients with non-metastatic MIBC were included: 92 (56.1%) underwent RC and 72 (43.9%) had RCT. Flow charts are shown in . Patients’ characteristics were comparable between RC and RCT groups (). Median age was 82 years (range, 80–100) in the RC group and 83 years (range, 80–93) in the RCT group. The majority of tumors were T2–T3 (91.5%) and N0 − Nx (92.7%). There were significantly more women in the RCT group (p = .01). Severe comorbidities were less frequent in patients treated with RCT (non-adjusted CCI ≥ 3: 22.2% versus 43.5%, p = .004). Eight (8.7%) patients had neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery. In the RCT group, 91.7% of patients received concurrent carboplatin or cisplatin alone and only two patients in association with 5 fluorouracil. Three patients were treated with paclitaxel and three other with gemcitabine (). The total radiation dose to the bladder is shown in . Data were missing in two patients. The majority of patients in the surgery group had open RC (89.1%), four (4.3%) had laparoscopic cystectomy and six (6.5%) had robotic cystectomy. The type of surgery was unknown in one patient. Urinary diversion types were ileal conduit, neobladder and Indiana pouch reservoir in 78 (84.8%), 7 (7.6%) and 2 (2.2%) patients, respectively. It was unknown in five cases.

Figure 1. Flowchart. RC: radical cystectomy; RCT: radiochemotherapy; RT: radiotherapy; CT: chemotherapy.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

Table 2. Chemotherapy in all 72 patients treated with radiochemotherapy.

Table 3. Radiation dose in 70 patients treated with radiochemotherapy.

Survival outcomes

The median follow-up was 2.30 years (range 0.03–7.40) in the RC group and 3.70 years (range 0.28–11.10) in the RCT group. The median OS was 1.99 years (95%CI 1.17–2.76) and 1.97 years (95%CI 1.35–2.64), respectively (p = .73) (). Among patients treated with RCT, 49 (68.1%) had died at the time of the analysis, versus 48 (52.2%) in the RC group. The 5-year OS did not differ significantly (21.70% versus 24.90%).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier’s overall survival curves for the radical cystectomy and radiochemotherapy groups.

Progressive disease was seen in 36 (39.1%) patients in the RC group and 32 (44.4%) patients in the RCT group (p = .2). Among patients with progression in the RCT group, 13 (18.1%) had loco-regional progression, 15 (20.8%) had metastatic progression and four (5.6%) had both. Metastatic sites were lung, bones, thoracic or retroperitoneal lymph nodes and liver in nine (12.5%), six (8.3%), six (8.3%) and five (7%) patients, respectively. The result of disease assessment after RCT was unknown in nine (12.5%) patients. In the RC group, five (5.4%) had loco-regional progression, 27 (29.3%) had metastatic progression and 16 (17.4%) had both. Metastatic sites were thoracic or retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones, liver and lung in 12 (13%), 11 (12%), 10 (11%) and eight (8.7%) patients, respectively. Other sites such as pelvic soft tissues and organs were seen in 11 (12%) patients. Median PFS was 1.25 years (95%CI 0.80–1.75) and 1.52 years (95%CI 1.01–2.04), respectively (p = .54) (). Five-year PFS did not significantly differ (20.60% versus 25.13%).

Prognostic factors

In univariate Cox regression analysis, disease progression was the only factor associated with poor OS (HR 9.59, 95%CI 6.25–14.71, p < .0001) ().

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for overall survival.

In multivariate analysis, disease progression remained significantly associated with OS (HR 10.27, 95%CI 6.63–15.91, p < .0001). However, the treatment modality did not have an impact on OS (HR 0.90, 95%CI 0.57–1.42, p = .66) ().

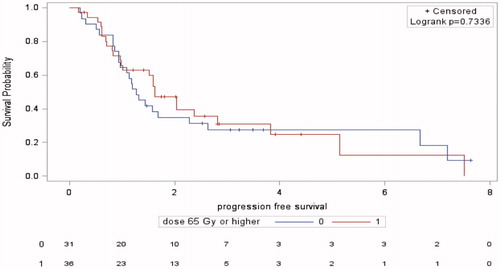

Patients receiving a dose of 65 Gy and higher had a median PFS of 1.63 year (95%CI 0.97–2.81) compared to 1.27 year (95%CI 0.94–2.28) in patients treated with a dose < 65 Gy (p = .73) ().

Discussion

We present survival outcomes in 164 elderly patients with non-metastatic MIBC treated with RC or RCT. To our knowledge, this is the largest population-based study reported in the literature about patients aged >80 years. We found no significant difference in OS and PFS between patients treated with RC or RCT. The Cox regression analyses showed no difference between the two modalities concerning their impact on OS.

In the surgery group, 5-year OS was 21.7%, which is lower than that reported in previous studies. Long-term results of RC were reported by Stein et al. in 1054 patients with a median age of 66 years. After a median follow-up of 10 years, the rates of OS were 60% and 43% at 5 and 10 years, respectively [Citation12]. However, our study concerned patients aged >80 years and survival outcomes following RC in such patients are not as good as those in younger patients. In fact, several studies have shown that patients aged 80 years and older have a significantly greater risk of disease recurrence, cancer-specific mortality and overall mortality than patients under 60 [13,14]. In our cohort, severe comorbidities (CCI > 3) and advanced tumors (T3–T4) were more frequent in patients treated with surgery than in patients who received RCT, which could explain the lower survival rates observed after surgery. However, the higher comorbidity score observed in the surgery group could not be explained as this is usually seen in patients treated with RCT.

In previously published series of MMT, 5-year OS ranged from 36% to 74% [Citation10]. The survival of patients treated with RCT in our study was similar to previously reported results. Efstathiou et al. reported 5-year OS of 22% in 348 patients included in successive prospective protocols evaluating MMT at the Massachusetts General Hospital [Citation9]. Mak et al. reported long-term outcomes of a pooled analysis of six RTOG prospective protocols evaluating bladder-preserving combined-modality therapy for MIBC in 468 patients [Citation8]. The median age was 66 years with 17% of patients aged 75 or more. There was no difference between elderly and younger patients (<75 year-old) for complete response rates (72% versus 73%; p = .78) and 5-year disease specific survival rates (71% versus 70%; p = .84).

No completed randomized controlled trial has compared RC with RCT. Our analyses showed no difference in survival between these modalities, suggesting that RCT in elderly patients, who are more likely to have comorbidities, is as effective as RC. These results are similar to other retrospective studies. In two population-based series from the United Kingdom, there was no difference in OS between RC and exclusive radiotherapy [Citation15,Citation16]. Five-year OS was 34.6% after RCT versus 41.4% after RC (p = .39) [Citation15]. Munro et al. found 10-year OS rates of 21.6% and 24.1%, respectively (p = .77) [Citation16]. More recently, Booth et al. found improved OS following cystectomy than with radiotherapy. However, patients treated with radiotherapy were older, had more severe comorbidities and only a proportion received concurrent chemotherapy. In addition, there was no difference in cancer-specific survival between the two treatment modalities [Citation17]. A large retrospective study using data from the SEER database reported a survival advantage achieved with both approaches. RC provided much longer OS in all age groups, except for octogenarians, in whom the OS advantage was limited to 3 months [Citation18].

As MIBC patients are often elderly and because MIBC is strongly associated with smoking, such patients are likely to harbor several comorbidities. One simple way to evaluate them is to use the CCI [Citation19]. Several studies have shown that a high CCI (>2) is associated with a significantly lower rate of PFS and OS following RC [Citation20,Citation21]. In addition, postoperative complications increase with increasing CCI [Citation22]. However, a high CCI in our cohort did not have an impact on OS.

This is the largest and most recent report on patients aged >80 years. In addition to its retrospective nature, our study has several other limitations. First, our results reflect the experience of multiple institutions across the world using different RCT protocols and with different cystectomy procedure volumes, thus making comparisons difficult. Furthermore, over the time-frame of inclusion (1988–2015), critical changes in the management paradigms for both RC and RCT have occurred. Second, we could not compare the toxicities of the two treatment modalities since post-operative complications and radiation-induced side-effects were not reported in the RISC database. Third, the T and N staging was based on radiological assessment after TURBT, thus leading to a possible misclassification. Finally, data regarding prognostic factors such as histological grade, multifocality, concomitant carcinoma in situ, hydronephrosis and tumor size were not available for analysis which is a major drawback in our study.

Conclusions

Bladder cancer is a disease of the elderly. The standard of care in MIBC is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by RC and PLND in fit patients. However, there is a significant risk of morbidity and mortality with these treatments, especially in the elderly. RCT seems an effective curative alternative. Physicians are confronted with a heterogeneous population with accumulating comorbidities, making treatment decisions complex. Our challenge is to identify preoperatively elderly patients at high risk of postoperative mortality and complications as well as major quality of life impairment. Performing a geriatric assessment as part of a multidisciplinary approach is mandatory in order to distinguish fit versus frail patients and to select the treatment strategy that optimizes patients’ outcomes. Studies that focus on this age category and incorporate geriatric screening tools should be encouraged.

Acknowledgments

The RISC investigators: N. Agarwal, D. Berthold, A. Bamias, J. Baniel, D. Bowles, L. Cerbone, R. Chen, G. Daugaard, R. Dreicer, N.M. Hahn, S. Hussain, M. Liontos, R. Mano, R. Morales-Barrera, A. Necchi, M. Nielsen, W. Oh, A. Smith, G. Sonpavde, S. Sridhar, S. Srinivas, C. Sternberg, C. Theodore and U. Vaishampayan.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflict of interest disclosures from any author.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386.

- Alfred Witjes J, Lebret T, Compérat EM, et al. Updated 2016 EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:462–475.

- Hautmann RE, de Petriconi RC, Pfeiffer C, et al. Radical cystectomy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy: long-term results in 1100 patients. Eur Urol. 2012;61:1039–1047.

- Hautmann RE, de Petriconi RC, Volkmer BG. Lessons learned from 1,000 neobladders: the 90-day complication rate. J Urol. 2010;184:990–994.

- Longo N, Imbimbo C, Fusco F, et al. Complications and quality of life in elderly patients with high comorbidities who underwent cutaneous ureterostomy with single stoma or ileal conduit after radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2016;18:521–526.

- Stein JP, Skinner DG. Radical cystectomy for invasive bladder cancer: long-term results of a standard procedure. World J Urol. 2006;24:296–304.

- Cancer of the urinary bladder-SEER stat fact sheets; 2016; [cited 2016 Dec 20]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/urinb.html

- Mak RH, Hunt D, Shipley WU, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer after selective bladder-preserving combined-modality therapy: a pooled analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group protocols 8802, 8903, 9506, 9706, 9906, and 0233. JCO. 2014;32:3801–3809.

- Efstathiou JA, Spiegel DY, Shipley WU, et al. Long-term outcomes of selective bladder preservation by combined-modality therapy for invasive bladder cancer: the MGH experience. Eur Urol. 2012;61:705–711.

- Ploussard G, Daneshmand S, Efstathiou JA, et al. Critical analysis of bladder sparing with trimodal therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;66:120–137.

- Galsky MD, Pal SK, Chowdhury S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:2586–2593.

- Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–675.

- Nielsen ME, Shariat SF, Karakiewicz PI, et al. Advanced age is associated with poorer bladder cancer-specific survival in patients treated with radical cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2007;51:699–706, 708.

- Patel MI, Bang A, Gillatt D, et al. Contemporary radical cystectomy outcomes in patients with invasive bladder cancer: a population-based study. BJU Int. 2015;116 Suppl 3:18–25.

- Kotwal S, Choudhury A, Johnston C, et al. Similar treatment outcomes for radical cystectomy and radical radiotherapy in invasive bladder cancer treated at a United Kingdom Specialist Treatment Center. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:456–463.

- Munro NP, Sundaram SK, Weston PMT, et al. A 10-year retrospective review of a nonrandomized cohort of 458 patients undergoing radical radiotherapy or cystectomy in Yorkshire, UK. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:119–124.

- Booth CM, Siemens DR, Li G, et al. Curative therapy for bladder cancer in routine clinical practice: a population-based outcomes study. Clin Oncol. 2014;26:506–514.

- Chamie K, Hu B, Devere White RW, et al. Cystectomy in the elderly: does the survival benefit in younger patients translate to the octogenarians? BJU Int. 2008;102:284–290.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383.

- Miller DC, Taub DA, Dunn RL, et al. The impact of co-morbid disease on cancer control and survival following radical cystectomy. J Urol. 2003;169:105–109.

- Koppie TM, Serio AM, Vickers AJ, et al. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity score is associated with treatment decisions and clinical outcomes for patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2384–2392.

- Schiffmann J, Gandaglia G, Larcher A, et al. Contemporary 90-day mortality rates after radical cystectomy in the elderly. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1738–1745.