Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth cause of cancer death and has a poor overall survival, with a five-year survival rate of 7% [Citation1]. The majority of patients (approximately 80%) have locally advanced and/or metastatic disease at diagnosis and are treated with palliative intent [Citation2–4].

At time of diagnosis, 30–40% of the patients report pain as a dominant symptom, which rises to 90% shortly before death [Citation5,Citation6]. Hence, successful pain management is often viewed as the key management in patients with advanced PDAC. In addition to neurolytic celiac plexus block (NCPB) [Citation7,Citation8] treatment with radiotherapy has shown to give improvement in pain control [Citation9–13]. However, in part of these studies the radiation is meant to improve local control and pain palliation is merely a (positive) side effect [Citation10,Citation13,Citation14].

In the Academic Medical Center (AMC) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, for patients with moderate to severe pain, a short course of palliative radiotherapy is applied. To evaluate the effect of this palliative radiotherapy we retrospectively analyzed all consecutive patients.

Material and methods

A total of 61 patients underwent palliative radiotherapy because of painful pancreatic cancer at the AMC between 1998 and 2015. Medical records and follow-up data were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. The institutional review board of the AMC granted an exemption from ethical review for this study.

The general characteristics of the patients are shown in . Median age at time of consultation was 62 years. The mean Karnofsky performance status (KPS) was 80%. At consultation 62% of the patients had metastatic disease. Mean pain duration before consultation was 4.5 months. Baseline pain scores, Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) 0–10, ranged from 4–10 with a median of eight. Eighty-five percent of the patients used strong opioids with a mean oral morphine equivalent (OME) daily dose of 147 mg (range 15–1920 mg).

Table 1. Patients and disease characteristics (n = 61).

The treatment schedule consisted of weekly radiotherapy in 1–3 weeks, with a total dose varying between 1 × 8 Gy and 3 × 8 Gy. Factors of importance in choosing a dose schedule were dependent of physician experience, tumor size and performance score. During the treatment, doctor consultation took place before the second and third fraction, to monitor and treat side effects and, if necessary, adapt the treatment.

The primary endpoint of our analysis was pain relief after radiotherapy. Evaluation of treatment was noted as ‘complete, any or no’ reduction of pain. Missing data were regarded as failure. Also the onset and duration of pain relief and treatment related toxicity were studied. Overall survival (OS), defined as the time between first consultation at the department of radiation oncology and death of any cause or last follow-up, was also analyzed.

Descriptive data and logistic regression analysis were applied using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 23, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Kaplan–Meier method was used for the OS.

Results

After consultation patients were planned according to three regimes; one, two or three fractions of 8 Gy, once a week. Forty-three patients (71%) were initially planned for a 3 × 8 Gy dose schedule, 16 patients (26%) for 2 × 8 Gy and two (3%) for 1 × 8 Gy. Eventually, 46, 39, 13 and 2% of the patients received 3 × 8 Gy, 2 × 8 Gy, 1 × 8 Gy and 1 × 6 Gy, respectively. In seventeen patients the intended treatment was changed due to improvement of pain (29%) or on the contrary, poor performance score (65%) and in one patient (6%) no explanation was given (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2). Anterior-posterior-posterior-anterior (APPA) radiotherapy, 3D conformal and intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)/volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) technique were used in 14, 56 and 30% of the patients, respectively. Mean clinical target volume (CTV) was 227 cc (range 8–2214 cc) and mean planning target volume (PTV) was 565 cc (range 74–3515 cc).

Radiotherapy was successful in 40 out of 61 patients (66%). Forty patients had pain relief after treatment. Four of these (7%) had complete pain relief (NRS of 0). The effect of radiotherapy was assessable in 54 patients and as mentioned previously missing data were regarded as failure. Baseline pain NRS was noted in 42 patients and after treatment pain NRS was evaluated in 10. A mean reduction of 5.3 points (from 7.7–2.4) was found in these 10 patients. We found no significant influence on pain relief from disease stage at consultation, KPS, morphine dose, radiotherapy target volume or radiotherapy dose. First pain relief was experienced one week after the end of radiotherapy based on evaluation of 25 patients. The median duration of pain relief was assessed in 11 patients and was 2.5 months (range 0.75–3.25 months).

Nausea grade –1–2 was reported in 31 (51%) patients and vomiting grade –1–2 in 13 (21%) patients. Transient flare of pain occurred in 20 (33%) patients. No grade 3 toxicity was noted.

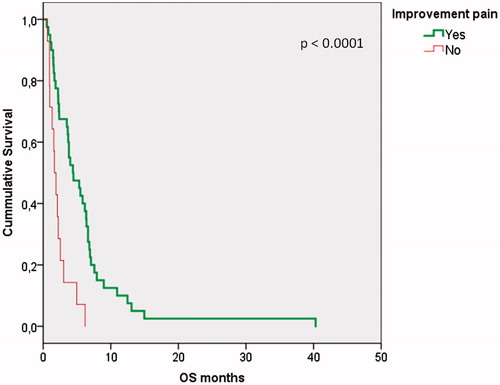

Median overall survival was 3.5 months (range 0.5–40 months). No statistically significant correlations were found in this study between KPS, PTV volume, radiotherapy dose and morphine dose regarding overall survival. Patients who responded to treatment had a significant (p < .0001) better OS of median 4.4 months (95% CI –2.0–6.8) vs. 1.7 months (CI 95% 1.1–2.3), respectively, as seen in the Kaplan-Meier curve in .

Discussion

This retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the effects of a short course of palliative radiotherapy for painful PDAC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study on the effect of radiation intended for pain palliation thus far. A high percentage of at least 66% of pain relief was achieved.

This is in line with previous studies on radiotherapy (65–100% response rates) [Citation9–13]. Various differences between these studies were seen with regards to patient selection and treatment. Morganti et al. used strict selection criteria, excluding patients older than 75 years and those with metastatic disease [Citation10]. Based on these selection criteria we would have treated much less patients, yet our response rate is similar, suggesting strict selection is not necessary. Interestingly, also the patient selection of Su et al. did not much influence pain response rates. A much smaller target volume of mean 43 cc (range –9–96 cc) was irradiated with stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) [Citation13] compared to our PTV of mean 565 cc, without differences in response rates. It should be emphasized that most radiotherapy studies reporting pain relief are high dose radiotherapy studies aiming at improvement of local control and/or disease free survival, rather than at pain palliation as such.

In this study we found comparable rates of gastro-intestinal (GI)-toxicity after radiotherapy as previously published studies. Large target volumes were not associated with more toxicity in our study, although a correlation between treated volume and toxicity might be expected. Remarkably, no significant difference in toxicity was seen between the high and the low dose groups of 24 Gy vs. ≤ 16 Gy.

The median OS of 3.5 months indicates selection of a poor prognostic patient group. Bernhards et al. reported a median OS of 2.3–2.8 months in Dutch metastatic PDAC patients [Citation14], in line with our results. Despite treatment of patients with a relatively poor performance and high pain scores we still managed to achieve a positive effect on pain. The extra poor survival observed in the non-responders may in part be due to a time bias; patients with a very short life span did not live up to evaluation of their pain relief or had other health problems making the reporting of eventual pain relief irrelevant.

The key limitation of our report is its retrospective nature. As a result we had a substantial amount of missing data concerning the endpoints of the study. To avoid bias we considered the seven patients of which we did not have information on pain relief (the primary endpoint) as failures. Despite being the largest study on painful PDAC, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Based on the current results and to overcome the aforementioned limitations, we have initiated the Short-term palliative radiation for painful irresectable pancreatic cancer (PAINPANC)-study, (Dutch trial register NTR5143) [Citation15]. With this prospective phase 2 study we hope to confirm the palliative effect of a short course of palliative radiotherapy (3 × 8 Gy) for painful pancreatic adenocarcinoma and obtain more knowledge about its duration and its influence on quality of life. Response is measured by two questionnaires: EORTC-QLQ-C15-PAL and the Brief Pain inventory (BPI). To date 27 out of 30 patients are accrued in this prospective study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, two-thirds of patients with local pain from pancreatic cancer experienced pain relief after a short course of palliative radiotherapy in our single institution retrospective study of 61 patients. No grade 3 or higher toxicity was observed. The prospective PAINPANC study is actively accruing.

Gati_et_al._Supplementary_material.docx

Download MS Word (18.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, et al. EUROCARE-5 Working Group. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE–5 – a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34.

- Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617.

- Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2004;363:1049–1057.

- Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, et al. Validation of the 6th edition AJCC Pancreatic Cancer Staging System: report from the National Cancer Database. Cancer. 2007;110:738–744.

- Yeo CJ. Pancreatic cancer: 1998 update. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:429–442.

- Bridenbaugh LD, Moore DC, Campbell DD. Management of upper abdominal cancer pain. JAMA. 1964;190:99–102.

- Yan BM, Myers RP. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for pain control in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:430–438.

- Eisenberg E, Carr DB, Chalmers TC. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for treatment of cancer pain: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:290–295.

- van Geenen RC, Keyzer-Dekker CM, van Tienhoven G. Pain management of patients with unresectable peripancreatic carcinoma. World J Surg. 2002;26:715–720.

- Morganti AG, Trodella L, Valentini V, et al. Pain relief with short-term irradiation in locally advanced carcinoma of the pancreas. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:258–262.

- Wolny-Rokicka E, Sutkowski K, Grządziel A, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of palliative radiotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: a retrospective analysis of single-institutional experiences. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:1088–1092.

- Comito T, Cozzi L, Zerbi A, et al. Clinical results of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) in the treatment of isolated local recurrence of pancreatic cancer after R0 surgery: a retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:735–742.

- Su TS, Liang P, Lu HZ, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy using CyberKnife for locally advanced unresectable and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Worl J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8156–8162.

- Bernards N, Haj Mohammad N, Creemers GJ, et al. Ten weeks to live: a population-based study on treatment and survival of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer in the south of the Netherlands. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:403–410.

- Nederlands trial register. [cited 2017 Nov 10]. Available from: http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/index.asp