Introduction

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman’s disease (iMCD) is a rare polyclonal lymphoproliferative disorder. It is characterized by systemic inflammatory symptoms, cytopenias and multi-organ dysfunction caused by proinflammatory cytokines [Citation1]. Even though hepatosplenomegaly and ascites are frequently associated with iMCD [Citation1], portal hypertension appears to be infrequent [Citation2]. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) of the liver is also an unusual condition, which is characterized by a generalized benign transformation of the hepatic parenchyma into small regenerative nodules, with minimal or absent perisinusoidal or periportal fibrosis [Citation3]. NRH is known to be associated with autoimmune, infectious, neoplastic, toxic and hematological conditions. It is usually asymptomatic, unless (non-cirrhotic) portal hypertension develops – estimated in 50% of the cases [Citation3]. NRH in iMCD patients has only seldom been reported [Citation4,Citation5]. We present a case of iMCD with portal hypertension and pathological features of NRH.

Case report

A 32-year-old male patient was diagnosed with Castleman’s disease (hyaline-vascular variant) in 2007. At that time, the patient presented with supraclavicular and mediastinal lymphadenopathies, without systemic symptoms and no active disease criteria. His medical history included a mild congenital factor V deficiency, without bleeding diathesis, and depressive and anxiety disorders for which he was medicated with escitalopram 20 mg id, olanzapine 10 mg id and lorazepam 2.5 mg id. There was no history of alcoholism. His family history was significant for scrotal cancer in his father.

Two years later, at age 34, the patient developed constitutional symptoms, consisting of malaise, anorexia, night sweats and weight loss, as well as epigastric pain. He weighted 70 kg, was afebrile, with normal blood pressure and heart rate. On physical examination, he had splenomegaly, but hepatomegaly, ascites and peripheral lymphadenopathy were absent. His laboratory evaluation revealed mild thrombocytopenia (118 × 109/L), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (84 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (3.26 mg/dL). Liver enzymes were raised: aspartate aminotransferase 58 U/L (normal lower than 45 U/L); alanine aminotransferase 75 U/L (normal lower than 35 U/L); gamma-glutamyl transferase 237 U/L (normal lower than 55 U/L); and alkaline phosphatase 457 U/L (normal range 30–120 U/L). Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia and positive antinuclear antibodies (1:160) were also present. Bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, total proteins and albumin were normal.

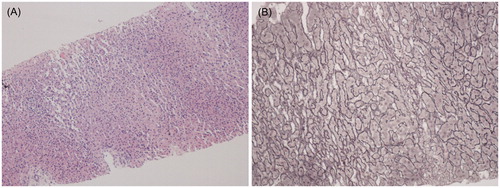

Abdominal ultrasound showed splenomegaly (20 cm) and a diffusely heterogeneous texture of the liver. Computerized tomography (CT) revealed left supraclavicular, mediastinal and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (the largest node with 4.3 cm), and confirmed an enlarged spleen and nonspecific changes in the liver parenchyma. 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging revealed increased uptake of FDG in those lymph nodes and no uptake in the spleen or liver. Histology of a supraclavicular lymph node showed abnormal follicles with hyalinization of germinal center, and an onion-skin aspect of the mantle zone, consistent with hyaline vascular variant of Castleman’s disease. HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen staining was negative in the lymph node tissue. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed a hypercellular marrow, with myeloid and megakaryocytic hyperplasia and mild lymphoplasmocytosis, without fibrosis. The patient was negative for HIV1/2, HHV-8, hepatotropic viruses (HAV, HBV, HCV, CMV, EBV), as well as for autoimmune, metabolic and granulomatous conditions. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed esophageal varices and signs of hypertensive gastropathy. Liver biopsy revealed sinusoidal distension and areas of nodular regeneration, without fibrosis in the perisinusoidal or portal areas, compatible with NRH (). Echocardiogram presented signs of pulmonary hypertension, with a severe enlargement of pulmonary trunk and right ventricle, with moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation and an estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) of 73–78 mmHg. Cardiology was consulted – pulmonary hypertension was confirmed by right heart catheterization and after exclusion of other causes of pulmonary hypertension, a portopulmonary syndrome was considered the likely cause.

Figure 1. Liver biopsy. (A) Routine staining reveals discrete nodular pattern, with enlarged hepatocytes. Centrilobular atrophy and sinusoidal dilation are also present between the nodules (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100). (B) Nodular areas consist of hepatocytes arranged in 2 cells thick plates (regenerating nodules) surrounded by zones of reticulin compression, where the hepatocytes are small and atrophic, without fibrosis (silver impregnation according to Gordon-Sweet, ×200).

At this time, a diagnosis of iMCD associated with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (due to NRH) and portopulmonary hypertension was made and the patient was treated with corticosteroids (prednisolone 60 mg/d), which he did not tolerate. Severe fatigue, lumbar pain and increased abdominal volume quickly ensued. His liver tests also worsened. Abdominal ultrasound with Doppler was remarkable for a dysmorphic liver, with relative reduction of the right lobe and discrete nodular features, splenomegaly (20 cm) and moderate ascites. Hepatic and portal venous flow was normal and there was no evidence of thrombosis. Hepatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed contrast-enhancing nodules on the diffusion-weighted images. Diuretic treatment was started (spironolactone and furosemide) and corticosteroids were progressively tapered and stopped. After one month, the patient developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGB) due to a ruptured varix and was treated with endoscopic ligation.

Given the patient’s clinical condition, he was treated with six cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone). Chemotherapy was well tolerated, with complete resolution of the systemic symptoms. Additionally, 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging revaluation showed significant reduction of the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes, maintaining slight uptake of FDG in one right hilar lymph node. The spleen’s characteristics did not change namely size and absence of FDG uptake.

The patient is 42 years old today, and his main complaint is fatigue for moderate efforts (NYHA class III). Besides the progressive reduction of PASP and pulmonary artery enlargement after chemotherapy, with a normal cardiac output, he maintained an elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (>5 Wood units), and sildenafil was recently introduced. He no longer has ascites, even though splenomegaly and esophageal varices are still present. No further bleeding episodes occurred. Inflammatory markers and liver enzymes have normalized, maintaining only a slight elevation of gamma-glutamyl transferase. His blood work shows a mild neutropenia and moderate thrombocytopenia, which are probably related to hypersplenism. Mediastinal masses are still present, but their size has been stable. Notably, the patient has no systemic inflammatory symptoms, and a watchful attitude with periodic clinical and imaging assessment was adopted.

Discussion

We present an unusual case of portal hypertension and NRH in a patient with iMCD. The available literature is scarce regarding such association, probably due to the rarity of both NRH and iMCD. Clinical features of Castleman’s disease are extremely heterogeneous, ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to vascular leak syndrome, organ failure and even death [Citation6]. However, severe life-threatening hepatic presentations are exceedingly rare. To our knowledge, there are only two other case reports of NRH in patients with MCD [Citation4,Citation5]. Molina et al. describe a case of MCD who died after an acute UGB, possibly in the context of portal hypertension (even though esophageal varices were not found). He was initially treated with corticosteroids, which he did not tolerate, and were eventually suspended. Autopsy revealed features compatible with NRH [Citation5]. Kiyuna et al. report a woman with NRH and MCD, treated with corticosteroids, with clinical improvement. Notably, she did not present signs of portal hypertension [Citation4]. There is an additional case reported by Abarca et al. who, despite not having NRH, also presented MCD and portal hypertension, with a fatal result due to hepatorenal syndrome. This patient presented with UGB due to esophageal varices [Citation2]. Our patient presented a more favorable outcome comparing to the other reports of MCD and concomitant portal hypertension. None of the other cases in the literature were treated with CHOP. Cytotoxic lymphoma based chemotheraphies are known to induce responses in severely ill iMCD patients [Citation7], with long-term remissions reported in up to 25% of cases [Citation8]. Newer therapies, such as siltuximab, an anti-interleukin 6 (IL-6) monoclonal antibody are now recommended [Citation9,Citation10], in light of the known association between Castleman’s disease and IL-6 [Citation11]. Additionally, transgenic mice expressing high level of IL-6 have developed NRH, similar to human NRH [Citation12]. Anti-IL6 therapy was not available at the time, and since the patient is currently stable, we have not medicated him further.

In conclusion, we describe an unusual association of iMCD with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension due to NRH, with a good outcome after CHOP, which had not yet been reported as a treatment option for this unique constellation of conditions.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Liu AY, Nabel CS, Finkelman BS, et al. Idiopathic multicentric Castleman’s disease: a systematic literature review. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e163–e175.

- Abarca M, Andrade RJ, García-Arjona A, et al. CASE REPORT: portal hypertension and refractory ascites associated with multicentric Castleman’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:697–702.

- Hartleb M, Gutkowski K, Milkiewicz P. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: evolving concepts on underdiagnosed cause of portal hypertension. WJG. 2011;17:1400–1409.

- Kiyuna A, Sunagawa T, Hokama A, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver and Castleman’s disease: potential role of interleukin-6. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:314–316.

- Molina T, Delmer A, LeTourneau A, et al. Hepatic lesions of vascular origin in multicentric Castleman’s disease, plasma cell type: report of one case with peliosis hepatis and another with perisinusoidal fibrosis and nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Pathol Res Pract. 1995;191:1159–1164.

- Dispenzieri A, Armitage JO, Loe MJ, et al. The clinical spectrum of Castleman’s disease. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:997–1002.

- Fajgenbaum DC, van Rhee F, Nabel CS. HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood. 2014;123:2924–2933.

- Herrada J, Cabanillas F, Rice L, et al. The clinical behavior of localized and multicentric Castleman disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:657–662.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. B-cell lymphomas (Version 3. 2017). [cited 2017 June 10]. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/b-cell.pdf

- Van Rhee F, Wong RS, Munshi N, et al. Siltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:966–974.

- Yoshizaki K, Matsuda T, Nishimoto N, et al. Pathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1989;74:1360–1367.

- Maione D, Di Carlo E, Li W, et al. Coexpression of IL-6 and soluble IL-6R causes nodular regenerative hyperplasia and adenomas of the liver. EBMO J. 1998;17:5588–5597.