Abstract

Background: Cancer survivors have to deal with symptoms related to cancer and its treatment. In Oncokompas, cancer survivors monitor their quality of life by completing patient reported outcome measures (PROMs), followed by personalized feedback, self-care advice, and supportive care options to stimulate patient activation. The aim of this study was to investigate feasibility and pretest–posttest differences of Oncokompas including a newly developed breast cancer (BC) module among BC survivors.

Material and methods: A pretest–posttest design was used. Feasibility was investigated by means of adoption, usage, and satisfaction rates. Several socio-demographic and clinical factors, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) were explored that might be associated with patient satisfaction. Barriers and facilitators of Oncokompas feasibility were investigated by evaluating nurse consultation reports. Differences in patient activation (Patient Activation Measure) and patient-physician interaction (Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interactions) before and after Oncokompas use were investigated.

Results: In total, 101 BC survivors participated. Oncokompas had an adoption rate of 75%, a usage rate of 75–84%, a mean satisfaction score of 6.9 (range 0–10) and a Net Promoter Score (NPS) of −36 (range −100–100) (N = 68). The BC module had a mean satisfaction score of 7.6. BC survivors who received surgery including chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were significantly more satisfied with Oncokompas than BC survivors with surgery alone (p = .013). Six facilitators and 10 barriers of Oncokompas feasibility were identified. After using Oncokompas, BC survivors scored significantly higher on patient activation (p = .007; r = .24), but not on patient-physician interaction (p = .75).

Conclusion: Oncokompas including a BC module is considered feasible, but needs further optimization to increase user satisfaction. This study shows the value of tailoring eHealth applications for cancer survivors to their specific tumor type. Oncokompas including the BC module seems to improve patient activation among BC survivors.

Introduction

There is a persistent high need for supportive care among breast cancer (BC) survivors concerning the impact of cancer and its treatment on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [Citation1], such as fatigue, anxiety, arm-shoulder disabilities, and menopause related concerns [Citation2–5]. To address these symptoms, survivors need to have access to supportive care services such as psychosocial care by a health care professional or self-help interventions (e.g., targeting a healthy lifestyle) [Citation6,Citation7]. Although supportive care has been proven effective for a range of cancer-related symptoms [Citation8–11], relatively few survivors benefit from it [Citation12] and as a result, many survivors have unmet care needs [Citation13,Citation14]. Additionally, reduced follow-up visits, resulting from an increasing evidence for the lack of effect of routine follow-up on early detection of cancer recurrence [Citation15], might lead to a further increase in unmet needs in cancer survivors. To increase usage of supportive care services, survivors are encouraged to adopt an active role in managing their own health. Hibbard et al. [Citation16] defined activated patients as ‘patients who believe they have important roles to play in self-managing care, collaborating with providers, and maintaining their health’. Patient activation is an element of patient engagement, referring to patients’ involvement in their health and healthcare overall [Citation17]. Several studies have shown that self-management methods, ranging from psycho-education interventions, exercise programs, and (online) self-help interventions targeting distress can encourage patient activation by providing information and teaching problem solving and coping skills [Citation16,Citation18–22].

To stimulate patient activation in cancer survivors, we developed the eHealth self-management application ‘Oncokompas’ [Citation23]. Oncokompas aims to increase the knowledge of cancer survivors on the impact of cancer and its treatment on various aspects of their personal HRQOL, and to facilitate access to supportive care. In Oncokompas, survivors follow three steps: measuring HRQOL by means of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) (‘Measure’), obtaining insight into their cancer-related symptoms through automatically generated tailored feedback (‘Learn’), and taking action by selecting optimal supportive care services (‘Act’). Because of the necessity for tumor-specific personalized information, self-care advice, and supportive care services [Citation12,Citation24], we developed a BC module as an additional part of Oncokompas. Next to the generic quality of life topics, the BC module comprises topics specifically targeted at consequences of BC.

The primary goal of the present study was to investigate the feasibility of Oncokompas including the BC module among BC survivors by (1) investigating adoption (intention to use Oncokompas), usage (actual use of Oncokompas), and user satisfaction; (2) exploring possible socio-demographic and clinical factors, and HRQOL that may influence user satisfaction; and (3) interviewing BC survivors on possible barriers and facilitators of the feasibility of Oncokompas. A secondary goal was to obtain insight into pretest–posttest differences with regard to patient activation and patient-physician interaction.

Material and methods

Study sample and procedures

Between September 2015 and September 2016, eligible BC survivors were invited to participate in this study by oncology nurses from five hospitals in the Amsterdam region in the Netherlands. The study was conducted according to regular procedures of the local ethical committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam. All participants signed informed consent.

BC survivors were eligible if they (1) were treated for BC with curative intent; (2) completed surgery, radiotherapy, and/or chemotherapy 1 month–2 years prior (survivors who still received adjuvant hormonal therapy or trastuzumab were also eligible); (3) were able to write, speak, and read Dutch; and (4) had some digital skills (self-reported verbally to the oncology nurse).

A pretest–posttest design was used, with a survey at baseline (T0) and a follow-up survey 1 week after providing BC survivors access to Oncokompas (T1). If survivors agreed to participate, they were first asked to complete the online baseline survey. Subsequently survivors received an invitation by e-mail to use Oncokompas. One week after receiving the invitation, survivors completed the online follow-up survey. Finally, survivors were asked for a consultation with their oncology nurse to evaluate Oncokompas. An additional semi-structured interview was held among a sub-sample of survivors by one interviewer (H. M.). The consultations and interviews were scheduled right after completion of the follow-up measurement (T1). After interviewing 10 survivors, data saturation was reached. Survivors who agreed in the informed consent to be contacted for an interview (all participants agreed) and who had completed the T1 survey were asked to participate. We randomly approached survivors from four hospitals to increase diversity of the sample. The goal was to gain more in-depth insight into user experiences of Oncokompas, posing three main questions: (1) What were your general expectations of Oncokompas?, (2) Can you tell something about your experiences with Oncokompas use?, and (3) Can you describe in what way you benefited from Oncokompas?. The interviews were conducted by telephone and took about half an hour. Quotes from the qualitative interviews were used to illustrate the quantitative data. One coder (H. M.) read all interviews. Relevant citations about general expectations, experiences, and benefits form Oncokompas were selected. The citations were checked for consensus by a second coder (CvU-K).

Intervention Oncokompas including the breast cancer module

Developmental process

To ensure sustainable usage, Oncokompas is developed following an iterative participatory design [Citation12,Citation23,Citation25,Citation26], meaning that we strive for constant optimization of Oncokompas while involving cancer survivors and healthcare professionals (HCPs) in each step of the development process. First, a needs assessment was conducted among BC and head- and neck cancer (HNC) survivors and HCPs [Citation12,Citation25]. Next, usability of a prototype of Oncokompas was tested by HNC survivors in two iterative cycles and HCPs participated in cognitive walkthroughs [Citation27]. Subsequently, HNC survivors participated in a multi-center study to assess feasibility of this prototype [Citation23]. In response to the results of this feasibility study, Oncokompas was optimized. Among others, we included a functionality for repeated use and redeveloped Oncokompas to enable usage on tablets.

Breast cancer module

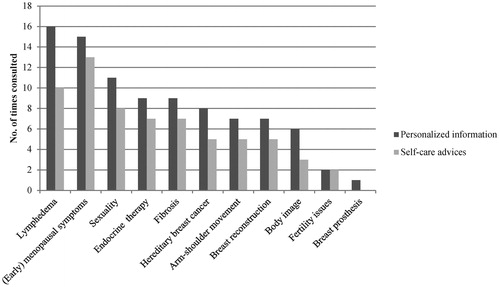

For BC survivors, specific topics were developed. An expert team consisting of nine BC survivors and 14 HCPs specialized in BC care were involved in the development process of the BC module: an oncological surgeon, a radiation oncologist, a medical oncologist, a clinical geneticist, a cosmetic and reconstructive surgeon, a physiotherapist, and eight oncological nurses. A list of relevant topics was composed, based on a non-systematic literature scan which focused on key review articles in the field of (late) effects of breast cancer and its treatment, and finalized with the expert team. The final version of the Oncokompas BC module encompasses 11 topics: endocrine therapy, (early) menopausal symptoms, body image, fertility issues, hereditary breast cancer, lymphedema, fibrosis, arm-shoulder movement, breast reconstruction, breast prosthesis, and sexuality (). The BC module is offered to BC survivors in addition to the generic modules of Oncokompas.

Table 1. Overview of domains and topics in Oncokompas.

Measure component

Oncokompas consists of three components: ‘Measure’, ‘Learn’, and ‘Act’ (see Supplementary File 1 for screenshots of the Oncokompas flow). Oncokompas starts with the ‘Measure’ component in which users first answer a set of questions regarding demographic and clinical characteristics. Based on these answers, a selection of personal relevant topics is composed (e.g., the topic ‘return to work’ is only relevant to those who are not retired). Subsequently, cancer survivors can independently complete PROMs targeting relevant topics in the following quality of life domains: physical, psychological and social functioning, healthy lifestyle, and existential issues ().

Learn component

Data from the ‘Measure’ component are processed in real-time and linked to tailored feedback to the user by means of algorithms. All algorithms are based on evidence based cutoff scores, or are defined based on Dutch guidelines, literature searches, and/or consensus by teams of experts. In the ‘Learn’ component, feedback on the topics is provided to the user by means of a three-color system: green (no elevated well-being risk), orange (elevated well-being risk), and red (seriously elevated well-being risk). Users receive personalized information on the topics, e.g., on the topic lymphedema, information is provided on symptoms of lymphedema and the proportion of BC survivors who suffer from it. Special attention is paid to clusters of interrelated symptoms (e.g., possible changes in weight related to endocrine therapy). The feedback in the ‘Learn’ component provides users with tailored self-care advice including tips, brochures, and links to relevant websites.

Act component

In the ‘Act’ component, users can select supportive care options that are personalized based on the individual PROM scores and preferences. If a user has elevated well-being risks, the feedback consists of options for self-help interventions. If a user has seriously elevated well-being risks, the feedback consists of options to contact a HCP. Users can print their results in a PDF format, to share with their HCP. In the case of repeated use of Oncokompas, the user is provided with insight in the course of symptoms during the cancer trajectory.

Outcome measures

A study-specific survey was composed comprising items on socio-demographic and clinical factors and questionnaires on health literacy, HRQOL, and need for supportive care (baseline (T0)), items on usage, satisfaction, and technical issues regarding Oncokompas (follow-up (T1)), and questionnaires on patient activation and patient-physician interaction (T0 and T1) ().

Table 2. Components in the baseline and follow-up survey.

Adoption and usage

Oncokompas was pre-defined as feasible for BC survivors in case of an adoption and usage rate of over 50%, a satisfaction score of at least 7, and a positive Net Promoter Score (NPS). This definition of feasibility is based on adoption and usage rates reported in previous studies on eHealth applications [Citation23,Citation28,Citation29]. Adoption was defined as the intention to use Oncokompas and was calculated as the percentage of BC survivors that agreed to participate in the study, returned the informed consent and completed the T0 survey. Usage was defined as the percentage of survivors that actually used Oncokompas as intended, based on logging data of the application.

Satisfaction

Mean satisfaction with Oncokompas was assessed by calculating the mean of two study-specific questions: general impression and user-friendliness of Oncokompas, on a 11-point rating scale: 0 (poor) to 10 (good). Satisfaction with the BC module specifically was assessed with the question ‘How do you score the BC module of Oncokompas?’, also on a 11-point rating scale. Furthermore, satisfaction was measured with the NPS ‘How likely it is that you would recommend Oncokompas to other BC survivors?’ on a 11-point rating scale: 0 (not likely) to 10 (very likely). The NPS is calculated by subtracting the percentage of detractors (who score 0–6) from the percentage of promoters (who score 9–10). The NPS ranges between −100 and +100. A positive score is considered good [Citation30,Citation31]. Additionally, user experiences on the three components ‘Measure’, ‘Learn’, and ‘Act’ as well as on the BC module of Oncokompas were assessed based on study-specific questions (dichotomized in yes/no format) in the follow-up survey (T1). We used logging data to report on the most frequently consulted components of the BC module. To gain insight into technical issues, we evaluated the type of technical problems survivors encountered using Oncokompas and the type of help they received to solve these problems (T1).

Associated factors

Socio-demographic (age (< 60 years versus ≥60 years old), education level (low versus medium/high), marital status (together versus single), occupational status (employed versus unemployed/retired)), and clinical factors (treatment modality (surgery alone versus surgery plus chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) and time since diagnosis (< 12 months versus ≥12 months)) were collected using study-specific questions. Scores were dichotomized due to the small sample size.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 is a cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire [Citation32]. In this study, a summary score was used as the outcome measure [Citation33]. A higher score represents a better quality of life [Citation34]. The EORTC QLQ-BR23 is a supplementary module meant to be used among BC survivors, consisting of four functional subscales and four symptom subscales [Citation35].

The validated 14-item Dutch translation of the self-reported Functional Communicative and Critical Health Literacy scale (FCCHL) was used to inform on how often patients have had problems with health information and the extent to which they extracted, communicated, and analyzed health information [Citation36,Citation37].

The Supportive Care Needs Survey Short Form 34 (SCNS-SF34) measured the need and level of need for supportive care in the last month on 34 items on a 5-point, two-level response scale [Citation38,Citation39].

Barriers and facilitators

After completion of the T1 survey, a consultation between a BC survivor and an oncology nurse was scheduled to obtain qualitative insight into the barriers and facilitators of Oncokompas use as experienced by BC survivors. During the consultations, a standardized interview report was used comprising three key components: (1) overall experience with Oncokompas, (2) congruence between the well-being score and survivors’ own perception, and (3) added value of the advice and supportive care options offered. If survivors did not make use of Oncokompas, the key components included: (1) reason for not using Oncokompas, and (2) needs and preferences towards the application in order to enable Oncokompas use. Inductive analysis was used to evaluate the reports, meaning that themes were identified gradually from the data [Citation40]. All written consultation reports were read several times by one coder (H. M.) to become familiar with the data. Relevant citations about barriers and facilitators were selected and synthesized into a list of key findings. A second coder (CvU-K) read this list and both coders met to discuss the findings until consensus was reached.

Pretest–posttest differences

The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) is a 13-item PROM on knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management of one’s health or chronic condition. Patients are asked to report their level of agreement with various statements on a 4-point rating scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) or to indicate that the item was not applicable. A total score can be obtained by calculating a mean score of all the applicable items (items which were answered on the 4-point scale), which is transformed to a standardized activation score ranging from 0 to 100 [Citation41].

The Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interactions (PEPPI-5) measures patients’ confidence in interacting with their main care provider using the short 5-item version scale. Patients can indicate on a 5-point rating scale (1 = not at all confident to 5 = completely confident) how confident they were that they e.g., knew which questions to ask or were able to make the most out of the visit [Citation42,Citation43].

Data-analyses

Analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL). Logging data from Oncokompas were analyzed in R version 3.3.1, a language and environment for statistical computing [Citation44]. We used descriptive statistics to report on adoption, usage, and satisfaction.

The outcome variable mean satisfaction with Oncokompas was not normally distributed and, therefore, dichotomized into two categories: a score <7 and a score of ≥7, in accordance with the cutoff point in the previous feasibility study of Oncokompas [Citation23]. Associations between satisfaction with Oncokompas and socio-demographic and clinical factors were explored conducting Chi-square tests and if appropriate Fisher’s exact tests. Associations between satisfaction with Oncokompas and HRQOL, health literacy, and need for supportive care were explored using a Mann–Whitney test. No corrections for multiple testing were applied due to the explorative approach of this feasibility study.

To assess the pretest–posttest differences in patient activation and patient–physician interaction, Wilcoxon-signed rank tests were conducted. The effect size estimate r for non-parametric tests was calculated by converting the z-score with the equation r = z/N [Citation45], and was interpreted using Cohen’s guidelines for r of .1 = small effect, .3 = medium effect, and .5 = large effect [Citation46]. We also analyzed factors that could be associated with an increase or decrease in patient activation and patient–physician interaction. Associations with socio-demographic and clinical factors were analyzed using Mann–Whitney tests; HRQOL, health literacy, and need for supportive care were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Survivors who completed the T1 survey, but did not make use of Oncokompas, were included in the analysis according to the ‘intention to treat’ principle. Statistical significance was assumed when p < .05 (two-tailed).

Results

Adoption and usage

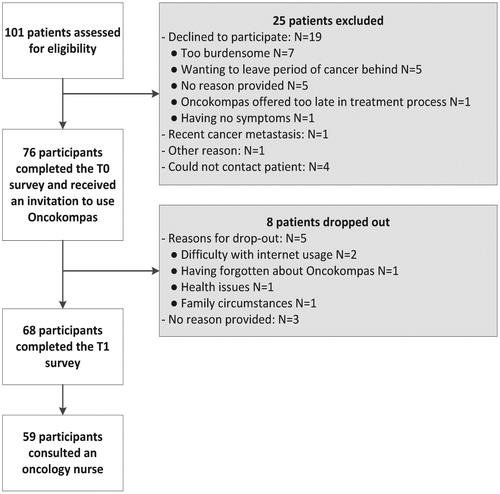

In total, 101 eligible BC survivors were invited to participate. shows details of the participant flow. The adoption rate of Oncokompas was 75%: 76 out of 101 survivors had the intention to use Oncokompas and filled in the informed consent and the T0 survey. Reasons for non-consent included finding participation too burdensome (N = 7) and wanting to leave the period of cancer behind (N = 5). During the study, eight survivors dropped out, leaving a study cohort of 68. The mean age was 56 years (range 32–85) and the mean time since diagnosis was 14 months (range 4–31). A full overview of the participant characteristics is shown in .

Table 3. Demographic and health characteristics of the participants.

The usage rate was 75% (57 out of 76, including dropouts) or 84% (57 out of 68, excluding dropouts) of survivors who made use of Oncokompas as intended based on the logging data. In total, 14 technical issues that hampered usage of Oncokompas were reported in the T1 survey: survivors were not able to find specific information, e.g., the supportive care overview (N = 6); they had trouble using Oncokompas on a smartphone (N = 2) or tablet (N = 1); and they received page errors (N = 2). Two survivors reported problems using the system attributed to a lack of internet skills (N = 2); and one participant had problems with Oncokompas due to using an older browser version (N = 1).

Satisfaction

Survivors who made use of Oncokompas (N = 57) evaluated satisfaction with Oncokompas with a mean score of 6.9 (range 0–10) (SD 1.8), 95% CI [6.4, 7.4]. The NPS was negative (−36) (range −100 to 100), consisting of 46% detractors, 10% promoters, and 44% passives.

When focusing on the user satisfaction of the ‘Measure’ component, for some survivors, the PROMs were intrusive (N = 9; 16%) (e.g., PROMS on intimacy and sexuality) or difficult to answer (N = 17; 30%). One of the survivors illustrated: ‘Some questions were difficult to answer, because you are forced to rate your situation. Sometimes you are doing fine and sometimes you’re not. I find it difficult to express that in numbers.’

The component ‘Learn’ in Oncokompas was viewed by 77% of the survivors (N = 44). The description of the outcomes was regarded as clear and understandable (N = 36; 82%) and presented in a structured way (N = 33; 75%). Approximately half of the survivors found the information about their health of added value (N = 23; 52%) and evaluated the outcome in congruence with their own perception (N = 24; 55%): ‘What I found nice is that it was recognizable. I was also a bit shocked by the results, that I needed more help than I expected. The psychological part, the fear and the alcohol use to suppress that feeling. Yes, that was confronting.’

More than half of the survivors (63%) (N = 36) read their self-care advice. These were scored as clear (N = 28; 76%) and complete (N = 27; 73%). In total, 35 survivors (61%) viewed the ‘Act’ component. Half of this group (N = 19; 54%) was interested in the supportive care options presented in Oncokompas and 12 of them (34%) had already undertaken action to improve their wellbeing consequently. One survivor declared: ‘The moment I saw what I filled in, I thought: I am not recovered yet. That was an eye-opener and it encouraged me to go see a psychologist. I was already hesitating, but when I looked at the results I thought: I believe I should do it.’

Of the 35 survivors who viewed the ‘Act’ component, some survivors intended to use Oncokompas in the future to look into their personalized advice and supportive care options (N = 22; 63%) or to complete Oncokompas again (N = 29; 51%). However, this did not apply to everyone: ‘It did not have added value for me anymore. Partly because I finished the treatments and partly because in my life, I adhere to my own compass.’

Regarding the BC module, 33 out of 57 survivors (58%) made use of one or more BC specific topics. The most frequently consulted personalized information and self-care advice on the topics from the BC module are lymphedema, (early) menopausal symptoms, and sexuality (). Survivors evaluated satisfaction with the BC module with a mean score of 7.6 (range 1–10) (SD 1.2), 95% CI [7.2, 8.0]. The topics were recognizable and survivors valued the BC specific information. ‘I found it important to read things that were recognizable, that you are not alone in this difficult period.’

Factors associated with satisfaction with Oncokompas

Survivors who were treated with surgery including chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were significantly more satisfied with Oncokompas than survivors who were treated with surgery alone (74% versus 25% satisfied with Oncokompas) (p = .013). Satisfaction was not significantly associated with any of the other socio-demographic, clinical factors, HRQOL, or need for supportive care.

Barriers and facilitators

In total, 59 survivors consulted an oncology nurse (50 users and nine non-users of Oncokompas). Ten barriers and six facilitators towards the feasibility of Oncokompas were mentioned five times or more. The most frequently mentioned barrier was ‘Oncokompas is (too) extensive’ and the most frequently mentioned facilitator included ‘the well-being score in Oncokompas is congruent with survivors’ own perception’. summarizes the barriers and facilitators mentioned.

Table 4. Barriers and facilitators towards the feasibility of Oncokompas (N = 59).

The qualitative interviews took 29 min on an average (range 21–38 min). The results matched with the barriers and facilitators mentioned in the consults with oncology nurses. For example concerning the barrier ‘Oncokompas has no added value’ one survivor declared: ‘Everything that was asked [in Oncokompas], I had already left that behind. I received supportive care options that I had already used. The information is outdated.’ Concerning the facilitator ‘Oncokompas provides a reflection and acknowledgement of one’s personal situation’ another survivor mentioned: ‘I recognized things and that was pleasant.’

Pretest-posttest differences

Patient activation (PAM score) was significantly higher after Oncokompas use than before (mean 60.5 versus 55.8), z = −2.71, p = .007, with a small effect size (r = .24). We found no significant associations between PAM scores and socio-demographic and clinical factors, HRQOL, or need for supportive care. Patient-physician interaction (PEPPI score) was not different after Oncokompas use than before (mean 20.4 versus 20.2), z = −.324, p = .75.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of Oncokompas including the newly developed BC module among BC survivors, and to explore pretest–posttest differences in patient activation and patient-physician interaction. The results showed that Oncokompas was considered feasible among BC survivors based on the definition of an adoption and usage rate of over 50%, but not with respect to the overall satisfaction score (6.9) and Net Promoter Score (−36). Oncokompas seems to activate BC survivors in managing their own health and health care.

The adoption rate and usage rate in this study (75% and 75–84%) were comparable with a previous study on the feasibility of Oncokompas among HNC survivors (64% and 75–91%) [Citation23]. The somewhat lower usage rate among BC survivors (compared with HNC survivors) may be explained by the use of logging data in the present study instead of self-reported data used in the study on HNC survivors. The satisfaction score and Net Promoter Score in this study (6.9 and −36) were lower than the previous feasibility study of Oncokompas among HNC survivors (7.3 and 1) and did not meet the predefined feasibility criteria. The difference in usage and satisfaction scores between BC and HNC survivors are in line with the results of an earlier study investigating the needs and preferences towards an eHealth application monitoring quality of life, showing that especially HNC survivors were positive about such an eHealth application, while BC survivors were more divided in their opinion [Citation12]. An explanatory factor might be the different symptom burden between BC and HNC survivors. Symptoms that are related to vital functions required for maintaining daily life (such as swallowing and speech) [Citation47,Citation48] are much more common among HNC survivors compared to BC survivors. Additionally, HNC survivors quite often have comorbidities [Citation49], which may further increase the numbers of symptoms. Another explanation could be that BC survivors are more critical eHealth consumers because eHealth interventions in oncology are mainly focused on BC patients and less on other populations such as HNC patients [Citation6].

Barriers of Oncokompas as found in the current study were in line with barriers found in a review study on adherence to online psychological self-help interventions in general, as e.g., the intervention is too generic, impersonal or not relevant to one’s personal situation [Citation50].

The low satisfaction score could also be attributed to the most frequently mentioned barrier of Oncokompas in this study; the application was found to be too extensive, especially regarding the amount of PROMs to be completed. This barrier was also mentioned in the earlier feasibility study among HNC survivors [Citation23]. To limit the amount of PROMs to be completed in the optimized version of Oncokompas used in this study, users were provided with two options: to fill in the complete range of PROMs, or to select specific topics of interest. Results, however, showed that BC survivors were still of the opinion that they had to put too much effort in answering questions, before they received personalized feedback and advice. According to several studies in the field of information processing, the large amount of information readily available on the internet makes people expect to find the answer to their questions directly, encouraging more screen-based and less in-depth reading behavior [Citation51,Citation52].

The percentage of survivors that completed one or more BC specific topics was 58%. This might be clarified by the fact that topics could be selected freely, as part of the enhanced usability of the system to lessen the amount of PROMs to be completed.

An interesting finding in this study is that the satisfaction score with the BC module was relatively high (7.6), compared with the satisfaction score of the generic Oncokompas (6.9). Although not statistically significant, this result confirms the added value of tailoring information as well as tailoring suggestions for supportive care services to individuals’ characteristics [Citation1,Citation6].

BC survivors who were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in addition to a surgery were more satisfied with Oncokompas than BC survivors who were treated with surgery only. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are associated with several health-related consequences such as fatigue, pain, and breast symptoms e.g., skin problems or an oversensitive breast area [Citation53–55]. These survivors might have more treatment-related symptoms and, therefore, it is expected that more topics in Oncokompas are of personal relevance to them. However, in contrast to our expectations, no association between satisfaction with Oncokompas and HRQOL was found (as measured with the generic global quality of life scale of the EORTC-QLQ-C30). Because the findings could also be a result of the multiple tests performed, further research is necessary to be able to draw conclusions on whether Oncokompas is more beneficial for specific patient groups. In the ongoing randomized controlled trial of Oncokompas, we will analyze the association between symptom burden, HRQOL and usage and satisfaction with Oncokompas more thoroughly.

The use of Oncokompas seems to activate BC survivors with regard to patient activation. This is in line with previous studies showing that (online) self-management interventions for cancer patients increase patient activation [Citation19,Citation56–58]. In qualitative studies on the expected perceived use of Oncokompas, patients also reported to expect that Oncokompas would allow them to take control and stimulate to act upon their symptoms [Citation12,Citation59], which is thus confirmed by the empirical quantitative data in the present study. Empowering patients using self-management applications is important because it provides patients with a solution to address their need for help concerning psychosocial and physical symptoms and contributes to improved survivorship cancer care aiming to increase quality of life, facilitate re-integration to work, and reduce healthcare consumption [Citation6].

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is that we included a diverse sample of BC survivors with a wide age range and that we used mixed methods to gain extended insights into the feasibility of Oncokompas. However, there are also some limitations. This study was a non-randomized single-arm exploratory study, and, therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. A randomized controlled trial is warranted and is currently ongoing [Citation7]. Additionally, results of this study might be less generalizable since the study sample consisted of relatively young BC survivors.

Conclusion

Oncokompas including a BC module is considered feasible, but needs further optimization to increase user satisfaction. Improvements have to be made to overcome the barrier of putting too much time and effort in completing PROMs before receiving feedback and advice. Theories in the field of information processing can be used to optimize the design of Oncokompas, for example, by enhancing the possibility of ‘selective shopping’, whereby users are encouraged to only complete PROMs that are of interest to them. Moreover, limiting the amount of demographic and clinical questions at the start might lower the effort needed to complete Oncokompas. This study shows the value of tailoring eHealth applications for cancer survivors to their specific tumor type. Further tailoring of Oncokompas by developing tumor-specific modules for other types of cancer is recommended. Oncokompas including the BC module seems to improve patient activation among BC survivors.

| Abbreviations | ||

| HRQOL | = | health-related quality of life |

| BC | = | breast cancer |

| NPS | = | Net Promoter Score |

| PROM | = | Patient Reported Outcome Measure |

| HCP | = | health care professional |

| HNC | = | head- and neck cancer |

Heleen_C._Melissant_et_al._Supplementary_File_1_20171026.pdf

Download PDF (1.9 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and health care professionals who contributed to this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pauwels EE, Charlier C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Care needs after primary breast cancer treatment. Survivors' associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Psychooncology. 2013;22:125–132.

- Abrahams HJG, Gielissen MFM, Schmits IC, et al. Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: a meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:965–974.

- Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, et al. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23:361–374.

- Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, et al. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2613–2619.

- Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:386–405.

- Aaronson NK, Mattioli V, Minton O, et al. Beyond treatment: psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. EJC Suppl. 2014;12:54–64.

- Van Der Hout A, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Witte BI, et al. Efficacy, cost-utility and reach of an eHealth self-management application ‘Oncokompas’ that helps cancer survivors to obtain optimal supportive care: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18:228.

- Meneses-Echávez JF, González-Jiménez E, Ramírez-Vélez R. Effects of supervised exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:77.

- Van Vulpen JK, Peeters PH, Velthuis MJ, et al. Effects of physical exercise during adjuvant breast cancer treatment on physical and psychosocial dimensions of cancer-related fatigue: a meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2016;85:104–111.

- Rogan S, Taeymans J, Luginbuehl H, et al. Therapy modalities to reduce lymphoedema in female breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159:1–14.

- Matthews H, Grunfeld EA, Turner A. The efficacy of interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes following surgical treatment for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2016;26(5):593–607.

- Lubberding S, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Te Velde EA, et al. Improving access to supportive cancer care through an eHealth application: a qualitative needs assessment among cancer survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1367–1379.

- Ellegaard MB, Grau C, Zachariae R, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and unmet needs among breast cancer survivors in the first five years. A cross-sectional study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1–7.

- Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1117–1128.

- Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. JCO. 2013;31:961–965.

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–1026.

- Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:223–231.

- Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet. 2004;364:1523–1537.

- Kuijpers W, Groen WG, Aaronson NK, et al. A systematic review of web-based interventions for patient empowerment and physical activity in chronic diseases: relevance for cancer survivors. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e37.

- van den Berg SW, Gielissen MF, Custers JA, et al. BREATH: web-based self-management for psychological adjustment after primary breast cancer–results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. *Jco. 2015;33:2763–2771.

- van de Wal M, Thewes B, Gielissen M, et al. Efficacy of blended cognitive behavior therapy for high fear of recurrence in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: the SWORD Study, a randomized controlled trial. JCO. 2017;35:2173–2183.

- Beatty LJ, Koczwara B, Rice J, et al. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a self-help workbook intervention on distress, coping and quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis. Med J Aust. 2010;193:S68–S73.

- Duman-Lubberding S, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Jansen F, et al. Feasibility of an eHealth application ”OncoKompas” to improve personalized survivorship cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2163–2171.

- Van Den Berg SW, Peters EJ, Kraaijeveld JF, et al. Usage of a generic web-based self-management intervention for breast cancer survivors: substudy analysis of the BREATH trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e170.

- Duman-Lubberding S, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Peek N, et al. An eHealth application in head and neck cancer survivorship care: health care professionals’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e235.

- Van Uden-Kraan CF, Lubberding S, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. Abstracts of the 2012 International MASCC/ISOO (Multiple Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society for Oral Oncology) Symposium. New York City, New York, USA. June 28–30, 2012. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(Suppl 1):1–283.

- Lubberding S, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Cuijpers P, et al. Abstracts of the IPOS 15th World Congress of Psycho-Oncology. November 4–8, 2013. Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2013;22(Suppl 3):1–374.

- Cnossen IC, Van Uden-Kraan CF, Rinkel RN, et al. Multimodal guided self-help exercise program to prevent speech, swallowing, and shoulder problems among head and neck cancer patients: a feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e74.

- Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, et al. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e152.

- Reichheld FF. The one number you need to grow. Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81:46–54, 124.

- Krol MW, de Boer D, Delnoij DM, et al. The Net Promoter Score – an asset to patient experience surveys? Health Expect. 2015;18:3099–3109.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376.

- Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:79–88.

- Fayers P, Bottomley A. EORTC Quality of Life Group, Quality of Life Unit. Quality of life research within the EORTC—the EORTC QLQ-C30. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(Suppl 4):S125–S133.

- McLachlan SA, Devins GM, Goodwin PJ. Validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) as a measure of psychosocial function in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:510–517.

- Ishikawa H, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:874–879.

- van der Vaart R, Drossaert CH, Taal E, et al. Validation of the Dutch functional, communicative and critical health literacy scales. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:82–88.

- Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C. Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:602–606.

- McElduff P, Boyes A, Zucca A, et al. The Supportive Care Needs Survey: a guide to administration, scoring and analysis. Newcastle: Centre for Health Research & Psycho-oncology; 2004.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116.

- Rademakers J, Nijman J, van der Hoek L, et al. Measuring patient activation in The Netherlands: translation and validation of the American short form Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health. 2012;12:577.

- Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, et al. Perceived efficacy in patient–physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:889–894.

- ten Klooster PM, Oostveen JC, Zandbelt LC, et al. Further validation of the 5-item Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interactions (PEPPI-5) scale in patients with osteoarthritis. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87:125–130.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria; 2017.

- Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2–18.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159.

- Burnip E, Owen SJ, Barker S, et al. Swallowing outcomes following surgical and non-surgical treatment for advanced laryngeal cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127:1116–1121.

- Jacobi I, van der Molen L, Huiskens H, et al. Voice and speech outcomes of chemoradiation for advanced head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1495–1505.

- Piccirillo JF. Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:593–602.

- Beatty L, Binnion C. A systematic review of predictors of, and reasons for, adherence to online psychological interventions. Int J Behav Med. 2016;23:776–794.

- Liu Z. Reading behavior in the digital environment: changes in reading behavior over the past ten years. J Document. 2005;61:700–712.

- Alexander PA. Reading into the future: competence for the 21st century. Educ Psychol. 2012;47:259–280.

- Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse L, et al. Variation in fatigue among 6011 (long-term) cancer survivors and a normative population: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2165–2174.

- Mols F, Beijers AJ, Vreugdenhil G, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, physical activity and health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors from the PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:512–522.

- Williams LJ, Kunkler IH, King CC, et al. A randomised controlled trial of post-operative radiotherapy following breast-conserving surgery in a minimum-risk population. Quality of life at 5 years in the PRIME trial. Health Technol Assess. 2011;15:i–xi, 1–57.

- McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:50–62.

- Cimprich B, Janz NK, Northouse L, et al. Taking CHARGE: a self-management program for women following breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2005;14:704–717.

- Solomon M, Wagner SL, Goes J. Effects of a Web-based intervention for adults with chronic conditions on patient activation: online randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e32.

- Boele FW, van Uden-Kraan CF, Hilverda K, et al. Attitudes and preferences toward monitoring symptoms, distress, and quality of life in glioma patients and their informal caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3011–3022.