Abstract

Introduction: Understanding the cause of their cancer is important for many cancer patients. Childhood cancer survivors’/survivors’ parents’ beliefs about cancer etiology are understudied. We aimed to assess survivors’/parents’ beliefs about what causes childhood cancer, compared with beliefs in the community. We also investigated the influence of clinical and socio-demographic characteristics on the participants’ beliefs about cancer etiology.

Methods: This two-stage study investigated the participants’ beliefs, by using questionnaires assessing causal attributions related to childhood cancer (stage 1) and then undertaking telephone interviews (stage 2; survivors/survivors’ parents only) to get an in-depth understanding of survivors’/survivors’ parents beliefs. We computed multivariable regressions to identify factors associated with the most commonly endorsed attributions: bad luck/chance, environmental factors and genetics. We analyzed interviews using thematic analysis.

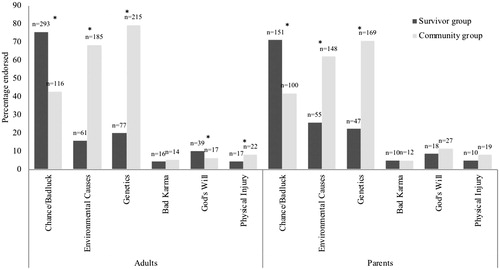

Results: Six hundred one individuals (64.6% survivors and 35.4% survivors’ parents) and 510 community comparisons (53.1% community adults, 46.9% community parents) completed the question on causal attributions. We conducted 87 in-depth interviews. Survivors/survivors’ parents (73.9%) were more likely to believe that chance/bad luck caused childhood cancer than community participants (42.4%). Community participants more frequently endorsed that genetics (75.3%) and environmental factors (65.3%) played a major role in childhood cancer etiology (versus survivors’ and survivors’ parents: genetics 20.6%, environmental factors: 19.3%). Community participants, participants with a first language other than English, and reporting a lower quality of life were less likely to attribute bad luck as a cause of childhood cancer. Community participants, all participants with a higher income and higher education were more likely to attribute childhood cancer etiology to environmental factors.

Conclusion: Causal attributions differed between survivors/survivors’ parents and community participants. Most of the parents and survivors seem to understand that there is nothing they have done to cause the cancer. Understanding survivors’ and survivors’ parents’ causal attributions may be crucial to address misconceptions, offer access to services and to adapt current and future health behaviors.

Introduction

After a childhood cancer diagnosis, patients and relatives often wonder ‘why me/my child?’. To seek an explanation for the occurrence of a threatening event is a natural human response [Citation1,Citation2], and patients and their families tend to ask oncologists to explain the cause of their cancer. Little is known about how patients settle on ‘a cause/multiple causes’ of their cancer. Patients may not listen purely to their oncologist when making this decision but may integrate other information, thereby developing their own ‘personal theory’ about cancer etiology [Citation3]. Deciding on a potential cause for a negative event is referred to as making a ‘causal attribution’ [Citation4]. Causal attributions can help patients to find meaning and create a better understanding of the negative event [Citation5].

It is important to understand the illness-related attributions of patients and healthy members of the community as they may influence health outcomes by prompting different health behaviors [Citation6]. In adult cancer patients, causal attributions can significantly impact patients’ psychological adjustment through cognitive-based coping strategies, as well as their service and information needs [Citation4,Citation7,Citation8]. A recent meta-review has shown that controllable attributions are associated with better adjustment [Citation7], whereas self-blame is associated with poorer outcomes [Citation4,Citation7]. Thus, causal attributions may be a potential future avenue for prevention and health behavior interventions [Citation6].

In adult cancer, the causes are better known and often related to risky health behaviors, environmental factors, aging and genetics. However, patients and the general community still develop their own beliefs about etiology, common risk factors that are not linked to their cancer [Citation8]. The most popular causal attributions in cancer patients and the community are lifestyle (e.g., smoking, diet), biological/genetic and environmental factors (e.g., air pollution, environment), suggesting that survivors and the community believe some factors (excluding lifestyle) are out of their control [Citation8,Citation9].

Causal attributions in childhood cancer patients and their primary caregivers are likely to differ to attributions made about adult-onset cancers. Most childhood cancer patients are diagnosed at a young age (often between 0 and 5 years), are rarely exposed to carcinogens or long-term environmental factors, and are not yet engaging in risky health behaviors [Citation10,Citation11]. Most pediatric cancers are considered to be sporadic, or caused by multiple factors [Citation11], with few environmental and exogenous factors firmly confirmed as risk factors [Citation12–14]. In many cases, the cause is unknown. Some patients and parents may look to genetics as a potential driver for childhood cancer because they may have other, older, affected family members. Yet causal mutations are only likely to influence about 10–15% of childhood cancers [Citation15]. However, this belief might shape their concerns for other family members and their child-bearing plans [Citation16]. As in adult cancer, understanding childhood cancer patients’ and parents’ causal attributions is important as they may influence psychosocial distress, and current and future health behaviors [Citation2,Citation6].

Causal attributions vary according to the patients’ different clinical and personal characteristics. A study from the United States showed that healthy adult women without a family history of cancer with a higher education who identified as white and had insurance, were more likely to attribute genetics as a cause of cancer [Citation9]. Very few, small studies have focused on childhood cancer survivors’ or parents’ causal attributions [Citation2,Citation17,Citation18]. One study grouped attributions into external (e.g., environmental, fate; 5/20 participants), internal attributions (e.g., heredity, ‘wrongdoing’; 4/20) and no attributions (e.g., just happened, don’t know; 6/20) [Citation2]. Those who made external attributions appeared to cope better than those who made internal or no attributions [Citation2]. Another study found that few parents believed that there was no cause for their child’s cancer, but more commonly attributed self-blame (e.g., smoking, diet) or a ‘trigger’ (i.e., cancer being latent in everyone and needing to be triggered by an accident or illness) [Citation17].

So far, no study appears to have assessed causal attributions on a large scale in pediatric oncology or explored possible associations with personal or clinical factors. Although beliefs may be influenced by information provided, verbally and in writing at the time of diagnosis and in interactions with oncology staff, there is currently no evidence regarding how survivors’ and survivors’ parents’ beliefs are shaped and whether they differ by characteristics such as diagnosis, family history or culture. Better understanding childhood cancer survivors’ and survivors’ parents’ causal beliefs and their characteristics, may assist oncologists and primary care physicians better address misconceptions and possibly improve adjustment to disease, health behaviors and satisfaction with care.

This mixed-methods study assessed causal attributions in four groups: a survivor group (childhood cancer survivors aged >16 years and survivors’ parents whose child was aged <16 years), and a community group (adults aged >16 years and parents with at least one child aged <16 from the general community with no history of cancer).

We compared survivor and community groups:

Personal beliefs about cancer etiology (i.e., causal attributions).

Socio-demographic factors associated with different causal attributions.

Clinical factors associated with different causal attributions (in the survivor group only).

Additionally, we conducted in-depth interviews with the survivor group to explore personal beliefs (causal attributions) in more depth and disclosure with healthcare professionals (HCPs).

Methods

This two-stage study is part of the Australian and New Zealand Children’s Haematology Oncology Group (ANZCHOG) survivorship study [Citation19]. In stage 1, we distributed surveys to families of childhood cancer survivors treated at one of 11 hospitals across Australia and New Zealand [Citation19]. Survivor aged ≥16 years, were invited directly. If the survivor was aged <16 years, we invited their parent(s) to participate on their behalf. In line with a sequential explanatory mixed-methods approach [Citation20], we offered participants who completed stage 1 the option to participate in stage 2; an in-depth telephone interview. Consistent with a sequential explanatory design, we used the survey data to inform the development of interview questions. We used the qualitative findings to further explain the quantitative data. [Citation20], We recruited a community comparison group to complete the survey.

Participants

Eligible survivors were diagnosed with any form of cancer under 16 years; were diagnosed ≥5 years prior to study participation; had completed active treatment; were proficient in English, were alive and in remission. To ensure eligibility, a clinician manually checked the list of potential participants at each hospital. We also screened the Australian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages to confirm the vital status of all participants. Given the potentially large time-lag between survivors’ cancer treatment and their study invitation, we used electronic matching software to cross-check hospital address records with white pages (an online national directory of residential addresses).

Eligible community participants were English speaking, did not have cancer and did not have a child with cancer. Community adults were aged 16–60 years to match the survivor group (may have had a child). Community parents had no age limit but had at least one child aged <16 years.

Procedure

The lead clinician at each hospital posted an invitation letter, a consent form, a survey and a pre-paid envelope to potential survivors/survivors’ parents. We telephoned non-respondents after four weeks up to four times (on average 1.73 calls per participant, SD=0.94, range=0–4). We designed the survey and interview guide with an expert committee and piloted with five survivors and five parents. We piloted the interview with two survivors and two parents. Experienced behavioral researchers administered the semi-structured telephone interview. The relevant ethics authority for all participating hospitals approved the study and it was endorsed by ANZCHOG.

We chose an online survey format to reach a wider sample of the general community. Community participants were reached through Pureprofile Pty Ltd, which contains a large panel of community members, most of whom respond to Australia Post’s surveys. We emailed community participants a link to the online survey. Participants provided consent before completing a series of screening questions to determine their eligibility. Participants received ∼$5(AUD) for their participation. Responses from identical IP addresses were deleted.

Measures

Primary outcome stage 1

Beliefs about what causes childhood cancer

We assessed causal attributions in accordance with Ferrucci et al. [Citation8], who coded the attributions of 775 cancer survivors into 9 types (5 internal, 4 external). We slightly modified these attributions to be more relevant for childhood cancer, resulting in six categories: chance/bad luck, environmental, genetics (runs in the family), ‘bad karma’ (deservedness), God’s will or purpose, and physical injury. Multiple attributions could be ticked.

The primary area of investigations for stage 2

In interviews, we assessed participants’ ‘personal theory’ about what caused childhood cancer with an open-ended question (based on Patenaude et al) [Citation3]: ‘We know that people consider many possible causes for their cancer which might differ from what doctors have told them. Have you ever had any thoughts about why you got cancer? These may not be things you’ve shared with others, just your own hypothesis’ and whether they have shared this theory with their HCPs.

Additional measures completed by all participants

Socio-demographic information

We assessed participants’ sex, age, education level, income, first language and religion ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survivors/adults from the community and survivors’ parents and community parents.

Quality of life

Assessed using the EQ-5D-5L, a six-item standardized measure of health status [Citation21], measuring health status across five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety and depression (‘no problem’ to ‘extreme problem’). The sixth item assesses self-rated health today with a visual analog scale (0: ‘Worst health you can imagine’, to 100: ‘Best health you can imagine’). We calculated a quality of life index value for each participant according to developer instructions, using the five domain items and the Australian sample (Model D) value set [Citation22]. A higher index indicates a better quality of life.

Measures completed by survivors and survivors’ parents

Medical characteristics

We assessed survivors’ primary diagnosis (categorized into leukemia, lymphoma, brain tumor and other), time since their primary diagnosis, time since last follow-up appointment, and whether their cancer had relapsed (yes/no/don’t know). We assessed their perceived worry/anxiety about developing late effects using response options ranging from 1: ‘not at all’ to 5: ‘a great deal’ which we grouped into 1: ‘not at all’, 2: ’a little’ and 3–5: ‘a great deal’.

Global satisfaction with care

Assessed using one item asking how satisfied the survivors were with their cancer-related follow-up care (1: ‘very unsatisfied’ to 5: ‘very satisfied’). The item was based on global satisfaction items used by prior studies [Citation23]. We categorized this variable into three groups: unsatisfied (i.e., very unsatisfied/unsatisfied), neither, and satisfied (i.e., satisfied/very satisfied).

Statistical analysis

We summarized clinical, socio-demographic data and data on causal attributions using descriptive statistics and compared survivor and community groups using t-tests and Chi-squared tests using Stata software (version 14.2: StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

For each attribution, we used separate uni- and multivariable logistic regression models to examine the association between each demographic variable (i.e., sex, education and income) and the probability of selecting that attribution adjusted for the group (community vs. survivor group, ). We conducted separate univariable logistic regressions for each causal attribution and clinical variables ( ) for the survivor group only. As we only conducted logistic regressions for attributions endorsed by at least 40 participants in each subgroup (), we did not run regression models on the attributions: ‘bad karma’, ‘God’s will’ and ‘physical injury’.

Figure 1. Proportion of survivors’ and survivors' parents endorsed causal attributions compared with community comparisons (*indicates significance level p < .05 between groups). Note: Participants were allowed to tick multiple causal attributions, Total number of survivors = 388, Total number of survivors’ parents = 213, Total number of community adults = 271, Total number of community parents = 239.

Table 2. Socio-demographic associations with causal attributions from univariable logistic regression adjusted for group (p values <.05 in bold).

Table 3. Clinical associations with causal attributions from univariable logistic regression in survivor group only (p values < .05 in bold).

We recorded and transcribed interviews verbatim. Two authors (J.V. and C.W.) developed the initial coding scheme guided by the six causal attributions used in our survey (see measure section). We analyzed interview data using thematic analysis as described by Miles and Huberman [Citation24]. We coded responses line by line and used NVivo11 to facilitate the coding of participant responses. No novel themes which were unrelated to the initial coding structure emerged. We extracted illustrative quotes and used these to inform quantitative findings. A random 20% of interviews were coded by two coders (J.V. and L.F.; 99.5% agreement as determined by the coding comparison in NVivo).

Results

There were 1132 participants, 622 individuals from the survivor group (response rate 53.8%, 404 survivors: mean age: 26.3 years, SD = 7.6; 218 survivors’ parents: child mean age: 13.05 years, SD = 2.5), and 510 in the community group (271 community adults: mean age: 27.3 years, SD = 7.4; and 239 community parents; and ).

Table 4. Clinical characteristics of survivors and children of survivors’ parents.

There were no significant differences between survivor and community adults in sex (p = .798) or age (p = .072) and no difference between survivors’ parents and community parents in sex (p = .122). We collected community data until we reached quotas for age, gender and region to match our survivor group. Therefore, it was not possible to calculate the response rate for the community group.

In survivors only, non-respondents differed significantly from respondents in sex and age (χ2 = 15.36, p < .001, t = –5.83, p < .001). Compared with respondents, non-respondents were younger (23.3 years) and were more likely to be male (55.8%). We did not perform a non-respondent analysis for the survivors’ parents, as we could not determine which parent would receive/complete the survey for their child.

In total, 361 individuals of the survivor group (226 survivors, 135 parents) opted-in for an interview. Eighty-seven (52 survivors, 35 parents) who were eligible and reachable completed the interview before we reached thematic saturation (assessed alongside data collection).

Cancer etiology (causal attribution)

In total, 601 participants (64.6% survivors) from the survivor group and 510 participants (46.9% parents) from community group answered the survey question on causal attributions.

Multiple attributions

Many participants recognized that childhood cancer could have several causal factors (44%). This differed between survivor and community groups, with 25% and 65% respectively endorsing more than one item in the survey as a causal attribution (p < .001). This finding was confirmed by interviewees (): ‘It’s a combination of genetic and environmental factors… across the road from me… was an electrical substation’. (Male survivor, 25 yo, lymphoma).

Table 5. Survivors’ and survivors' parents’ beliefs about their childhood cancer.

Bad luck/chance

The survivor group was significantly more likely to endorse ‘bad luck/chance’ as a causal attribution than the community group (73.9% survivor group, 42.4% community group; p < .001; ). As one survivor said: ‘It wasn't genetic, it wasn't environmental; I think it was just bad luck. I'm pretty sure that they said that there was nothing that could have prevented it’. (Female survivor, 19 yo, Non-Hodgkins lymphoma).

In the multivariable regression of socio-demographic factors, participants with a first language other than English (OR 0.57, CI: 0.33–0.97 p = .039) and the community group was less likely to attribute ‘bad luck/chance’ than the survivor group (OR 0.27, CI: 0.19–0.39, p < .001, data not shown). In multivariable regression, participants with a higher quality of life (OR 1.19, CI: 1.03–1.37, p = .021) were more likely to attribute ‘bad luck/chance’. In the univariable regression in the survivor group we found those indicating worrying more about late effects were less likely to endorse bad luck/chance: (e.g., ‘a great deal’ OR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.34–0.97, p = .044, ).

Genetics

The second most commonly endorsed attribution by the survivor group was ‘genetics’ (‘it runs in the family’; 20.6%). This was the most endorsed attribution by the community group (75.3%; p < .001).

Only a few survivors and survivors’ parents associated genetics with cancer: ‘No one actually said why, but I just believe it is genetics. I’m kind of born with it…I’m the unlucky one’. (Survivor, 37 yo, brain cancer).

In the multivariable regression, we found that the community group was more likely to attribute genetics than the survivor group (OR 12.42, CI: 8.23–18.74, p < .001). In the univariable regression in the survivor group, we found participants worrying more about late effects were more likely to attribute genetics (e.g., ‘a great deal’ OR = 2.42, 95% CI: 1.33–4.43, p = .009, ).

Environmental causes

The third most commonly endorsed attribution in survivor group was environmental causes (19.3%). By contrast, environmental causes were the second most commonly endorsed attribution in the community group (65.3%, p < .001).

Some survivors and survivors’ parents were convinced that smoking or other carcinogens and chemicals such as those in paint played a role: ‘I’m aware that every other mother in the oncology ward smoked during pregnancy’. (Survivor, 29 yo, Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, (ALL)).

Interviewees did not appear to endorse a strong role for environmental factors, however, it did ‘cross their minds’: ‘when I do my gardening and I spray things and don’t use any protection…. But you know, I’ve not ever realistically thought that [it caused cancer]’ (Mother, 14 yo survivor, Neuroblastoma).

In the multivariable regression, we found that the community group was more likely to attribute environmental causes than the survivor group (OR 8.84, CI: 5.92–13.20, p < .001). All participants with a higher income and participants with post-school qualifications were more likely (OR = 1.48, CI: 1.05–2.09, p = .025, OR = 1.72, CI: 1.19–2.49, p = .004 respectively) to attribute environmental causes. Survivors diagnosed with lymphoma, brain tumors and other tumors were less likely to attribute environmental factors than survivors diagnosed with leukemia (p = .042). Survivors worrying more about late effects were more likely to attribute environmental factors (e.g., ‘a great deal’: OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.02–4.08, p = .041).

Other attributions

The least often endorsed attributions were ‘bad karma’, ‘God’s will’ and ‘physical injury’ for all participants ().

The few interviewees who believed that ‘bad karma’ played a role described the attribution as a sort of punishment or malediction: ‘I thought I was just being punished, because I didn't really want to have another child’. (Mother, 14 yo survivor, brain cancer).

One mother who associated the brain cancer with a physical injury suggested that her son: ‘was so out of the box he used to climb up so high and then jump off something…I wondered if all that jumping off things somehow rattled something in his brain and caused some sort of dysfunction/malfunction somewhere?’ (Mother, 16yo survivor, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma).

Disclosure of personal theories regarding cancer etiology with HCPs

Most interviewees had not shared their beliefs with their HCP: ‘Nah, I haven’t [told them]. When I go to the oncologist I’ve been there for a reason. They’re generally behind so they kind of want to get you out of there’. (Male survivor, 25 yo, lymphoma) Other parents did share their beliefs for confirmation: ‘We went and spoke to [the Genetics department] and did a bit of family history stuff and they, they pretty much confirmed our views that it wasn’t genetics’. (Mother, 12 yo survivor, ALL, ).

Discussion

This is one of the first and largest studies describing childhood cancer survivors’ and survivors’ parents’ beliefs about cancer etiology in comparison to a community group. Our mixed-methods results demonstrated differences in causal attributions between the survivor group and community group. Interviewees tended not to share their theories about childhood cancer etiology with their HCP and future research should assess the meaning-making process of their beliefs. We found some socio-demographic (e.g., higher income and education) and clinical characteristics (e.g., diagnosis, worrying about late effects) associated with different causal attributions.

Survivors and survivors’ parents most commonly endorsed ‘bad luck/chance’, whereas community participants mainly attributed environmental factors and genetics. These results may indicate that HCPs are helping families understand that the causes are often unknown or related to chance/bad luck and there was nothing parents could have done which could have prevented cancer in most cases. In addition, families might also actively search for additional information on the causes of childhood cancer online or elsewhere to gain a better understanding [Citation25–27]. Bad luck/chance might not be a satisfying reason for some survivors/survivors’ parents and they might still try to find a different cause. This might also explain why most survivors/survivors’ parents did not disclose their personal theory about what has caused cancer with their HCP which is consistent with previous findings [Citation2]. Community participants may have less knowledge about the causes of childhood cancer which might explain why they more often selected multiple attributions. Also, they may be unaware that the causes are often unknown and are therefore more likely to attribute environmental factors and genetics, factors likely playing a greater role in adult cancers and factors which are often discussed in the media. Similarly, a previous study has shown that only a minority of community participants attributed the chance as a causal attribution [Citation9]. In more recent years important global initiatives such as the Childhood Cancer Awareness Month have been started which aim to raise awareness and raise funds through global charities and social media platforms. However, our findings highlight the importance to further increase the awareness of childhood cancer among the general community potentially through a wider media coverage to avoid stigma and self-blame in affected families.

Despite genetic causes (i.e., that cancer ‘runs in families’) being identifiable in only 10–15% of childhood cancers and new evidence is only emerging [Citation15], this was the second most common attribution made by survivors’ and survivors’ parents and the most common attribution made by community participants. Like our finding genetic factors were often attributed to cancer by healthy adult women without a family history of cancer [Citation9], indicating that healthy participants might be more likely to attribute factors out of their control. This can be hazardous as it might prevent participants from adopting healthy behaviors.

Even though only a few studies have found associations between childhood cancer etiology and environmental factors [Citation12,Citation13,Citation28,Citation29], our results showed that one-quarter of the survivor group attributed environmental factors to their (child’s) cancer. Similarly, a study of patients with the ten most common adult cancers showed that one-quarter of adults attributed environmental factors as a possible cause for their cancer [Citation8]. Consistent with large epidemiological studies [Citation13,Citation29], survivors and survivors’ parents attributed environmental factors more often if diagnosed with leukemia. Interview participants often reflected on potential exposures or wrongdoing during pregnancy or early childhood. Similar to our findings, a previous study by Ruccione et al who asked parents about any concerns they may have about the causes of their child’s cancer, showed that environmental factors such as quality of air, water and food but also occupational or household exposures were the biggest concerns for parents [Citation30]. Environmental factors might be more common factors for many adult cancers, which might also explain why more participants in the community group attributed environmental factors as a cause of childhood cancer.

Previous studies indicated that when cancer patients make external attributions (i.e., believe the cancer was not caused by their own actions/behavior such as genetics or bad luck), they may cope better with their treatment and experience fewer negative feelings (e.g., self-blame, long-term guilt) [Citation2]. Similarly, we found an association for attributing bad luck/chance and better quality of life. However, we did not find any associations with other causal attributions and well-being including satisfaction with follow-up care. In univariable regression, we also found that religious participants were less likely to attribute bad luck/chance as a cause of childhood cancer potentially indicating a less fatalistic approach. However, further research is needed to understand different religious and cultural factors associated with causal attributions. Highly educated participants and participants with a higher income were more likely to associate environmental factors to cancer etiology suggesting that socio-economic factors may influence health perceptions such as identifying health risks (i.e., carcinogens) and possibly adapting future health behaviors [Citation9]. Similarly, participants worrying about late effects were more likely to attribute genetics and environment as potential causes for (their) cancer possibly indicating that the awareness of future health risks might shape their belief and concerns about their health.

A strength of this study is the use of mixed-methods data which has the advantage of overcoming the weakness of each methodology. Another strength is the large sample size and the population-based approach, including both survivors and parents. A further strength is the use of a community comparison group. We were also able to report some data from non-respondents of the survey, which is relatively uncommon in this area [Citation31]. Even though respondents and non-respondents were significantly different in sex and age, we successfully recruited both attendees and non-attendees of follow-up clinics and therefore reached a wider range of survivors. The results need to be interpreted with some limitations. Some groups were likely underrepresented, including linguistically diverse populations (as the surveys were administered in English). Another limitation is the potential for self-selection bias: some participants (e.g., those with higher education) might have been more motivated to participate. Further, the time since diagnosis was long and beliefs might have changed over time. This study relied on self-report cross-sectional data, we are therefore not able to conclude whether the different associations caused their personal beliefs. Our response rate was modest, however likely because we contacted survivors/survivors’ parents who have been decades from diagnosis and many survivors were disengaged from the tertiary system where we identified and contacted them from.

Clinical implications

Searching for a cause for a disease is a natural human response. However, an explanation might not always be found. Even though many individuals of the survivor group attributed bad luck to childhood cancer development, misconceptions around genetics and environmental factors seemed common. Therefore, it seems crucial that HCPs discuss their patients’ personal beliefs about cancer etiology with their patients and families to reveal potential misconceptions. Discussions might help to move families away from attributions which are unlikely to be helpful. Offering access to genetic services and information about genetics and environmental factors might enable some families to plan for the future (e.g., family planning), help other family members learn about their future cancer risk and potentially decrease their worries. Future patients and families may have access to new information about the etiology of childhood cancer as new evidence is emerging and the field of genetic/genomic testing in pediatric oncology is rapidly advancing [Citation14].

Conclusion

Causal attributions differed between the survivor and community group. Survivors and survivors’ parents mostly endorsed bad luck/chance, whereas community group endorsed genetics and environmental factors. Few associations with different causal attributions were found. HCPs seem to reassure parents and survivors that the cancer is not because they have done something wrong. Understanding a cause of a patients’ cancer might be valuable in the acceptance of a disease and help patients and families to cope with the negative event. This might not only be important during early diagnosis but also later during survivorship. Potential misconceptions should be discussed, and additional information and services provided if required to adapt current and future health behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lucy Hanlon, Gabrielle Georgiou, Alison Young, Luke Fry and Sanaa Mathur for their contributions to this research. We would also like to thank each of the recruiting sites for this study, including Sydney Children’s Hospital Randwick, the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, John Hunter Children’s Hospital, the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Monash Children’s Hospital Melbourne, Royal Children’s Hospital Brisbane, Princess Margaret Children’s Hospital, Women’s and Children’s Hospital Adelaide, and in New Zealand, Starship Children’s Health, Wellington Hospital and Christchurch hospital. We would like to thank Rebecca Hill (BPsych), Joanna Fardell (Ph.D.), and Kate Hetherington (Ph.D.) for conducting the interviews. We would like to thank Nancy Briggs and Mark Donoghoe for their statistical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kelley HH, editor. Attribution theory in social psychology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska; 1967.

- Bearison DJ, Sadow AJ, Granowetter L, et al. Patients' and parents' causal attributions for childhood cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1994;11:47–61.

- Patenaude AF, Basili L, Fairclough DL, et al. Attitudes of 47 mothers of pediatric oncology patients toward genetic testing for cancer predisposition. Jco. 1996;14:415–421.

- Hall S, French DP, Marteau TM. Causal attributions following serious unexpected negative events: a systematic review. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22:515–536.

- Lipowski ZJ. Psychosocial aspects of disease. Ann Intern Med. 1969;71:1197–1206.

- Lykins EL, Graue LO, Brechting EH, et al. Beliefs about cancer causation and prevention as a function of personal and family history of cancer: a national, population-based study. Psycho-oncology. 2008;17:967–974.

- Roesch SC, Weiner B. A meta-analytic review of coping with illness: do causal attributions matter?. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:205–219.

- Ferrucci LM, Cartmel B, Turkman YE, et al. Causal attribution among cancer survivors of the 10 most common cancers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29:121–140.

- Rodriguez VM, Gyure ME, Corona R, et al. What women think: cancer causal attributions in a diverse sample of women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2015;33:48–65.

- Steliarova-Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001-10: a population-based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):719–731.

- Stiller CA. Epidemiology and genetics of childhood cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:6429–6444.

- Spycher BD, Lupatsch JE, Huss A, et al. Parental occupational exposure to benzene and the risk of childhood cancer: a census-based cohort study. Environ Int. 2017;108:84–91.

- Kuehni C, Spycher BD. Nuclear power plants and childhood leukaemia: lessons from the past and future directions. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w13912.

- Greaves M. A causal mechanism for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(8):471–484.

- Zhang J, Walsh MF, Wu G, et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2336–2346.

- Botkin JR, Belmont JW, Berg JS, et al. Points to consider: ethical, legal, and psychosocial implications of genetic testing in children and adolescents. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:6–21.

- Eiser C, Havertnans T, Elser JR. Parents' attributions about childhood cancer: implications for relationships with medical staff. Child Care Health Dev. 1995;21:31–42.

- Yi J, Kim MA, Parsons BG, et al. Why did I get cancer? Perceptions of childhood cancer survivors in Korea. Soc work in health care. 2018;13:1–15.

- Vetsch J, Fardell JE, Wakefield CE, et al. Forewarned and forearmed: long-term childhood cancer survivors' and parents' information needs and implications for survivorship models of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:355–363.

- Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2014;35(1):29–45.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736.

- Rabin ROM, Oppe M. EQ-5D-5L User Guide, (ed Version 1.0). Rotterdam. 2011.

- Lee DS, Tu JV, Chong A, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with quality and outcomes of care after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:1938–1945.

- Miles B, Huberman A, editors. Qualitative data analysis: an expended sourcebook. London, UK: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Tuffrey C, Finlay F. Use of the internet by parents of paediatric outpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:534–536.

- Nagelhout ES, Linder LA, Austin T, et al. Social media use among parents and caregivers of children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2018;35(6):399–405.

- Kilicarslan-Toruner E, Akgun-Citak E. Information-seeking behaviours and decision-making process of parents of children with cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:176–183.

- Spycher BD, Lupatsch JE, Zwahlen M, et al. Background ionizing radiation and the risk of childhood cancer: a census-based nationwide cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:622–628.

- Baker PJ, Hoel DG. Meta-analysis of standardized incidence and mortality rates of childhood leukaemia in proximity to nuclear facilities. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:355–363.

- Ruccione KS, Waskerwitz M, Buckley J, et al. What caused my child's cancer? Parents' responses to an epidemiology study of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1994;11:71–84.

- Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, Doolan EL, et al. Participation in psychosocial oncology and quality-of-life research: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e153–ee65.