Abstract

The treatment of the Significant Polyp and Early Colorectal Cancer lesion has evolved from strategies formally based around didactic pathological diagnoses (‘cancer or no cancer?’) and the limited availability of certain techniques (‘what can we do?’) into a more advanced situation of understanding diagnostic uncertainty (‘the what if scenario’), factoring patient preference & approach to risk and the availability of a wide range of techniques in both the rectum and the colon. It is now the former rather than the latter which are driving decision making and treatment strategies (‘what should we do’). Decisions are now made around possible planes of ‘safe’ excision and options for completion treatment and these issues are discussed in full. The range of techniques available extends to cover advanced endoscopic endoluminal therapies as well as the recently expanded range of surgical options for endoluminal treatment particularly in rectal lesions. This review looks at these and considers two new paradigms the therapeutic strategies available and those which are evolving.

Principles of treatment – strategies

Historically, strategies for therapeutic interventions for colorectal neoplasia have developed driven by one of two factors: either a histopathological diagnosis, for example the management of ‘early rectal cancer’ or according to the evolution and availability of therapeutic techniques, for example the widening use of endoluminal snare resections. Developments in endoluminal assessment and, for rectal lesions particularly, improved multimodal imaging options have led to an increasing appreciation of the key role that the choice of excisional plane plays in the therapeutic strategy for these lesions. Together with the move towards formally structured MDT decision making not just for rectal cancer but all significant colorectal neoplasms, the underlying therapeutic strategies have to some extent been re-evaluated and consideration given to how the various options for intervention can be seen to fit together to form an ‘interventional armamentarium’ rather than competing paradigms. The perspective on treatment decisions is now more ‘what should we do?’ than ‘what can we do?’

Choice, risk, and options

An essential factor which is gaining more prominence in the process is the patient’s choice and approach to risk. This predominantly applies to rectal lesions where the range of interventions is widest, the options for sequential completion treatment and ‘salvage’ treatment most numerous and where the consequences of ‘overtreatment’ or failed treatment can be the most telling in terms of impact on quality of life. This has also led to a widening recognition of strategies which build on the ‘what if’ scenarios as applicable to individual patients recognizing the innate uncertainty present in any assessment and the need to offer options for further interventions in the face of unexpected histopathology results. While the consideration of completion and salvage surgery is beyond the scope of this article they do play heavily into some treatment planning algorithms. Only the primary treatment strategies will be considered here.

Basic strategies for intervention

Colonic and rectal neoplasms are often considered separately and often with different basic approaches to treatment. There is the obvious difference that the security of the mesorectal fat envelope provides for the range of interventions making almost any form of transluminal technique safer in terms of risk of ‘transmural’ complications. There may be some differences in biological behavior between rectal and colonic carcinomas such as risk of lymphovascular spread but, in reality, the basic strategies upon which decision making can be shaped are arguably the same throughout the colorectum, just with fewer options open in the colon. Definitions of what actually constitutes the rectum may be anatomically relevant but in practical clinical terms, anything not accessible to one of the range of transanal, transluminal techniques is essentially a colonic lesion for the purposes of therapeutic options. The lack of equivalent platforms to transrectal surgery in the colon means that non-resectional therapies are limited mainly to endoscopic approaches. One key development in the thinking around therapeutic options is to move away from a specific diagnosis ‘adenoma versus carcinoma’ and away from ‘endoscopy versus surgery’ and to consider (a) what tissue planes might be considered appropriate for a treatment strategy, (b) what sort of specimen is best to deliver treatment and pathology allowing for subsequent options, and then (c) what options best fit these objectives given the site and characteristics of the lesion and the patient; ‘what plane?’ and ‘what specimen?’ before ‘what tool?’

The intact submucosal plane – putatively benign lesions

For lesions assessed and deemed to have an apparently intact submucosal plane, an excision anywhere in the submucosal plane is appropriate. The question remains if and the extent to which a single piece mucosectomy is superior to a piecemeal excision.

There seems little doubt that from the point of view of subsequent pathological assessment a single piece specimen is superior whatever the size of the lesion; the potential issues of pseudoinvasion, and epithelial misplacement may best be considered only when full orientation and ‘contextualization’ of the lesion is provided which is best in the single piece specimen. As a minimum, enbloc resection of all dominant nodules should be an aim given the higher propensity for them to contain either areas of malignancy or the epithelial changes leading to diagnostic uncertainty [Citation1,Citation2]. Whether there is any advantage in terms of recurrence comparing single piece to piecemeal techniques is unclear particularly when there is such variation in the use of endoscopic and surgical options for the ‘single piece’ approach although review guidelines do conclude that there is [Citation3]. It seems likely that complications such as bleeding and stricturing are no different.

The intact deep submucosal plane – ‘up to sm2’ early lesions

A strategy which is becoming much more widely adopted is the concept of the ‘intact’ deep submucosal plane. Whilst selection of lesions which demonstrate this feature on imaging/assessment will encompass both benign and early invasive lesions (effectively those up to Kikuchi sm2) it specifically allows tailored non-full thickness excision intervention both in the rectum and, where possible, in the colon while keeping the option for more radical completion treatment open in the knowledge that deeper tissue planes have not been opened. This is, arguably, most relevant and common in rectal lesions but is likely to become a more important concept as transluminal colonic techniques advance. There is evidence that by using multimodal assessment and a strategy to opt for ‘deep’ mucosectomy in such lesions the use of local excision as definitive treatment for rectal lesions at least can be significantly increased in the context of a specialist SPECC MDT [Citation4].

This strategy necessarily requires a specific deep submucosal excision with a single-piece specimen to ensure the essential plane is maintained and thus restricts therapeutic options to ESD and, in the rectum, ESD and the surgical procedures capable of the mucosectomy plane dissection.

The intact outer muscularis propria – ‘up to T2’ early rectal carcinomas

In a similar fashion, the selection of lesions suitable for full thickness excision is an essential attribute of assessment. The role of patient choice and involvement in decision making is absolutely essential in this context. The diagnostic uncertainties are the highest and the therapeutic options and consequences of sequential treatment the most relevant. It is not just for the elderly or infirm that non-resectional treatment is appropriate. Younger patients are often acutely aware of the consequences of radical treatment, particularly in the rectal lesion and offering a suitable plane of excision for lesions which may include up to an early T2 carcinoma is highly significant. While predominantly an issue for rectal lesions, the options for combined laparo-endoscopic non-resectional treatment and endoscopic full thickness excision mean that colonic lesions should not be forgotten albeit that the imaging capabilities necessary to select cases with any degree of reliability lag behind those for the rectum.

Treatment modalities

Endoscopic endoluminal techniques

Endoluminal endoscopic techniques have evolved considerably beyond the simple ‘lift and snare’ en bloc polypectomy for the small semi-pedunculated lesion. By definition the majority of SPECC lesions are of a size or morphology that prevents one piece snare excision for the entire lesion, predominantly on size criteria but occasionally due to diagnostic uncertainty. The range of lesions seen and the complexities of decision making have led to a number of guideline or consensus statement publications which look at both diagnosis and options for intervention [Citation1,Citation2,Citation5,Citation6]. The emphasis in publications varies between the practical aspects of process and technique to recommendations regarding strategy and decision making although these are mostly still centered on the simple ‘pivot’ of the decision on the presence/suspicion or otherwise of malignancy. An issue which these guidelines have also considered is the increasing range of options and differing levels of expertise offered and required in their delivery.

En bloc polypectomy (‘simple’ EMR)

The hot snare resection is the widely accepted standard technique for both pedunculated and semi-pedunculated lesions up to around 15 mm, usually involving one of a range of pre-injection fluids both as a hemostatic adjunct and also to deploy a thermal cushion to reduce the risk of deep mural injury [Citation1]. Lesions with a larger ‘head’, over 20 mm, can be accommodated by the technique with extra-large resection devices provided a thinner stalk is present to allow pretreatment. Generally, the typical SPECC lesion has a larger sessile component or multiple morphologies with one or more dominant nodules making the single en-bloc EMR resection difficult beyond about 20 mm diameter. Whilst the plane of excision is within the submucosal plane in most cases, the extent of submucosal tissue resected varies and is impossible to accurately assess from the specimen unless muscularis propria smooth muscle cells are seen. Often the depth varies across the snare plane and control of the plane is extremely difficult. This makes it only really applicable to the ‘intact submucosa’ group of lesions.

Even in ‘simple’ EMR, en-bloc resection remains the goal. The risk of unexpected malignancy can be correlated with several factors () but even in smaller lesions there is a risk of unexpected malignancy [Citation7] and the ‘whoops’ polypectomy remains a recurring headache for the SPECC MDT especially where margin positivity exists.

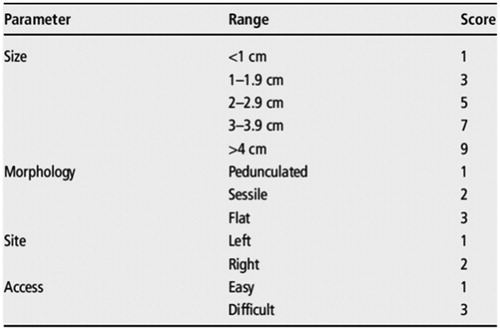

Table 1. Risk factors for the presence of malignancy in a SPECC lesion.

Of all endoscopic interventions, with adequate preparation and pre-injection, most would conclude that the risk of perforation is 1% or less and of major hemorrhage 2% or less [Citation5]. The risk of adenoma recurrence is very low in the simple EMR although there is evidence that the risk of recurrence increases with the documented use of ‘margin therapy’ such as application of APC or diathermy ablation [Citation1,Citation6]

Extended piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection (pEMR)

For the ‘true’ SPECC lesion, which encompasses lesions described as LSTs or NPCPs [Citation5], the commonest approach in the Western hemisphere is still likely to be the extended piecemeal EMR. The objective remains excision in the submucosal plane although as with the simple EMR, the depth of resection is uncertain and hard to control precisely. Visualization of the plane is better particularly once the resection gets underway and an appreciation of the extent to which the submucosal connective tissue has been resected can usually be estimated but, as before, histopathological assessment remains essentially difficult and use in the second ‘intact deep submucosal plane’ group is less precise.

Because these lesions much more frequently have one of more of the risk factors for malignancy present, it is usual that recommendations exist for the thorough assessment and multidisciplinary discussion of the lesion prior to treatment. It is also recognized that there are risk factors for incomplete excision () and a classification of lesions to allow for common comparisons of ‘difficulty’ and understandable communications between clinicians has been proposed in the UK ( and )

Table 2. Risk factors for the incomplete pEMR endoscopic resection (from [A]).

The technical skills of the interventional endoscopists undertaking these proceeds is now more clearly understood and has built on both clinical experience and the developments in device technology in the therapeutic options available. Even in the more extensive lesions situated on the right side of the colon perforation rates of <2% and major bleeding rates of <5% are the standard key Performance Indicators (KPIs) in the UK and similar figures are the norm across Europe. Recurrence rates of <10% are the standard aim and, depending on the cohort of lesions described, are routinely reported in larger series although there is evidence that incomplete resection and recurrence rates are worse in ‘complete’ pEMR excisions compared to ESD [Citation8].

The Achilles’ heels of the procedure remains the plane of excision and the issue of malignancy. Recommendations are that dominant nodules should always be resected en-bloc given their propensity to contain foci of undiagnosed malignancy and the overriding necessity for delivering an R0 specimen should carcinoma be present [Citation1,Citation3]. This may not always be easy with two or more dominant nodules, especially where coalescent and most guidelines only recommend consideration of the technique where malignancy has been confidently excluded.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

Originally developed and most widely used in Japan and in the upper GI tract, the formal submucosal plane excision by endoscopic means, ESD, offers the essential characteristics required where the therapeutic strategy demands a single piece specimen within a degree of certainty of the completeness of submucosal excision. The recognized limitations of the technique are mostly to do with the practicalities of providing or delivering it; a long, shallow learning curve, time consuming & prolonged procedure, need for overnight or longer hospital stay, and costly instrumentation. It is mostly these factors rather than innate problems with the technique that limit its wider use in western countries given that the safety profile seems able to at least match that of pEMR [Citation9]. Arguably, if the practical limitations could be discounted, ESD could provide the optimum approach to a majority of SPECC lesions in the colon especially. It is currently recommended for lesions ‘with high suspicion of superficial submucosal invasion’ which equates to the ‘intact deep sm plane’ concept or for lesions which cannot be ‘optimally removed by snare based techniques’ such as pEMR [Citation1].

ESD offers an endoscopic option equivalent to the surgical mucosectomy techniques available in the rectum for colonic lesions even where a Kikuchi sm1/2 carcinoma may be present. As considered elsewhere, the main issue is the relatively limited ability to accurately define this population in the colonic lesions with no really reliable imaging techniques in wide use. This means a reliance on intraluminal inspection or, if considered appropriate, the ‘non-lifting sign’ to define a target population although the ability of these techniques to reliably exclude the sm3/T2 lesion is uncertain.

Surgical endoluminal techniques

Surgical endoluminal techniques are currently limited to those in the rectum or very distal sigmoid ‘in range’ of the platform chosen. Not strictly limited to ‘true’ rectal lesions both mucosectomy and full thickness excision can be used even in the peritonealized rectum/sigmoid.

Mucosectomy versus full thickness

Mucosectomy should be delivered en-bloc and should deliver the deep plane of excision at the submucosal/muscularis propria interface. Whilst ESD is a controlled technique, the surgical mucosectomy usually involves a more accurate dissection process, without the possible distortion engendered by the use of injection of fluid into the tissues. This may have benefits in the sm1/2 lesion where providing a clear R0 resection is one of the ‘key blockers’ to accepting local excision for definitive or risk-compromise treatment. What is uncertain is the relative performance of surgical mucosectomy against both pEMR and ESD in the treatment of the putatively benign but large SPECC lesion both in the context of early complications and also longer term recurrence-free survival.

The surgical mucosectomy offers an option not so easily available via endoscopic techniques in the face of (a) dense or widespread scar underpinning the lesion, (b) recurrent lesions where neoplastic tissue may be harbored within scar sitting on the muscularis propria, and (c) where previous intervention has distorted anatomy making pEMR or ESD difficult. Whilst the endoknife options available in ESD are similar to the needle knife which can be deployed at surgery, the manual application and pressure available to assist in scar separation make it an excellent tool in these complex situations where anatomical planes are often obliterated.

Full thickness excision, in the context of the SPECC lesion is usually performed in the perimuscular plane is response to the ‘intact outer muscularis’ strategy. Deeper excisions are really the province of compromise or multimodality treatment of established carcinoma.

There are clinical scenarios in which surgical endoluminal techniques are either contra-indicated or present problems. The risk of general anesthesia in the population undergoing transanal treatment is low [Citation10] but there is evidence of the adverse impact of general anesthesia in preexisting cognitive impairment making surgical options requiring GA less attractive even in the context of early malignancy. The larger caliber of all surgical platforms makes the presence of anal stenosis, previous anal sphincter surgery and loss of rectal compliance issues which might lead to a preference for the narrower caliber offered by endoscopic methods although, the loss of rectal compliance may also limit the flexibility of position required for pEMR or ESD.

Platforms

A number of surgical platforms exist for transanal surgical approaches. While the Transanal Endoscopic MicroSurgical (TEMS) equipment is the most established, other platforms exist offering both rigid access (such as the Transanal Endoscopic Operating system, TEO) and flexible access (such as the TransAnal Minimally Invasive Surgery approach, TAMIS).

In many respects, the differences between the commonly used platforms may suit them to particular techniques and strategies but none preclude use in the treatment of the SPECC lesions. There are, however, no useful comparative data between platforms and the choice, where available, remains mostly one of experience, pragmatism or convenience. Some of the main differences are summarized in but a few relevant issues merit consideration.

Table 3. Technical comparisons of common transanal surgical platforms.

Fixed or flexible platform

This difference in platform access may be of greater relevance than previously considered. The assumption that flexibility and single patient positioning is necessarily a benefit in access platforms may be less appropriate than it seems. SPECC lesions in the rectum often exist over the rectal folds, in the upper rectum involving the rectosigmoid junction or have mixed morphology with several dominant nodules. The ability to actively distort, straighten or flatten the rectal folds or manipulate the lesion itself within the workspace using the device’s rigid platform may offer some direct practical benefits in the hands of experienced operators. The firmly fixed nature of the camera system and instrument access limits the field of operation at any one time but offers the most controlled operating field. The rectosigmoid junction is not always easy to access in the supine position as often used with flexible platforms and whilst a modest challenge to the anesthetic team, the lateral and prone positions required by rigid devices may offer better access in this area particularly in females.

Limits of scope access

Rigid scope systems allow for positioning of the operating field down to the mid anal canal offering the chance to complete the entire procedure via the single platform. Those systems involving a transanal flexible deice to maintain pneumorectum often necessitate a hybrid procedure with some open peranal technique used for the lowest extent of lesions down to this level. The upper accessible limit may also be effectively higher in the rigid system since, once the scope is delivered up to the lesion, the operating field is in the same position relative to the scope fixing the lumen whereas the increased distance from the flexible port device may make rectal stability less for higher lesions.

Vision system

The various systems offer either full true 3D vision by twin optic operating microscope, virtual 3D via post-image processing of a 2D camera head or simple 2D (standard or high definition). There are no studies to assess the impact of the 3D view but many operators argue that, particularly for mucosectomy excisions, the true 3D view may hold advantages both for accuracy of dissection and speed of procedure although these are uncertain.

Combined surgical-endoscopic techniques

The initial lack of a true transluminal resection equivalent to the transanal full thickness excision led to the evolution of two strategies targeted at extending the role of local excision in colonic SPECC lesions to avoid the impact and possibly the risks of standard resection, laparoscopic or otherwise.

Laparoscopic–endoscopic resection (LER)

The first has been combination laparoscopic surgery and synchronous endoscopic techniques, usually of the pEMR approach. This was initially aimed at extending the endoscopic ‘envelope’ to include lesions previously thought unsuitable for endoscopic excision such as those at flexures, those beyond the reach of colonoscopes due to difficult looping or those with a higher risk of full thickness injury. The somewhat contradictory needs of the pneumoperitoneum and the pneumocolon demand a carefully co-ordinated approach but it is mainly the inability to position the patient and the necessity for general anesthesia that has seen this approach rather stall in its adoption. It still offers an approach where resection might otherwise have to be entertained and it may also find a niche in the more complex full thickness local excisions although whether the risk associated with this is that much different from conventional laparoscopic resection is unclear.

Endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR)

True EFTR is really still in its infancy in terms of operating systems. ‘Over the scope’ devices currently predominate and whilst developments in ‘operating colonoscopes’ may open this option out for larger, more complex lesions, currently it is still only in use for small lesions. The use of this approach is not covered specifically in any of the guideline or consensus documents and evidence for its use is still mostly in the form of cases series and retrospective reviews. Data on safety and efficacy compared to specialist center experience with ESD are lacking. Its role in suspected polyp cancers is slightly controversial in any but those considered unsuitable for other interventions, such as resection of laparoendoscopic surgery. One area of use may be to augment endoscopic access in sites precluding endoscopic treatment such as the flexures, the ‘difficult’ sigmoid, or cecum especially around the appendix orifice.

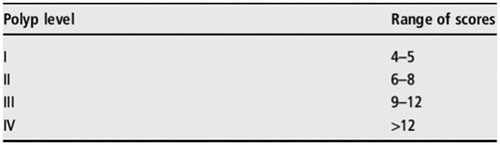

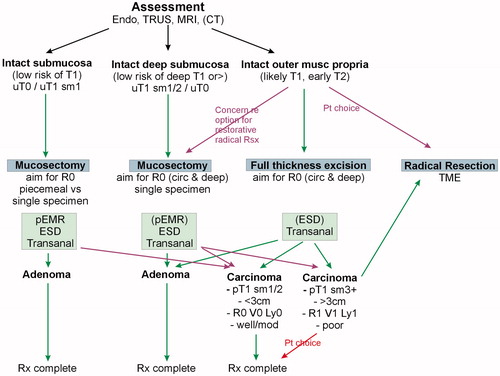

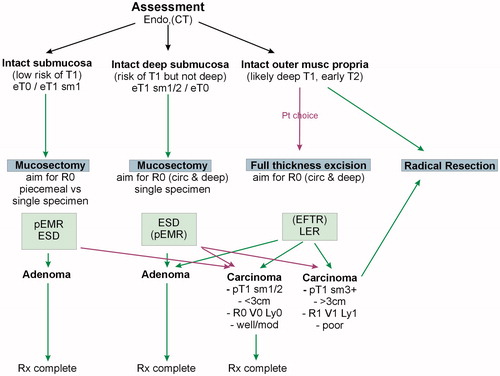

Algorithms

The application of these strategies and the blending with the treatment options will necessarily vary and depend to some extent on the guidelines followed as well as local or national policies and availability of expertise. Two such algorithms are shown in and which have been used to deliver options to patients in the context of a SPECC MDT.

The SPECC MDT in treatment decisions

One move is clearly developing across sites, platforms, and approaches; a fully constituted multidisciplinary team with access to the full range of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies is most likely to offer the best treatment selection for patients. ESGE guidelines recommend discussion including an interventional endoscopist prior to surgery for colorectal neoplasms unless deep submucosal invasion is suspected [Citation1]. It is likely that the reverse should also be considered; no endoscopic intervention for significant lesions without discussion including all transluminal options where they may be relevant, particularly rectal lesions. How best to deliver this concentration of expertise is an important consideration. Patients should not be exposed to needless repeated endoscopic procedures but ensuring rapid or even real time teleconferencing access to opinions including good imaging and video footage is often practically difficult even if it is likely to aid correct patient and strategy selection.

Future developments

ESD technology has advanced considerably in recent years. While further evolutions in the equipment available are likely, the most important development for the technique is how widespread, and how easy access to it as a primary treatment over pEMR is going to become.

Advanced endoluminal operating systems, possibly even incorporating microengines and mini robotic devices seem a very real possibility and would expand the options for treatment in colonic lesions. It is possible to foresee the blurring of distinctions between interventional endoscopists of a primarily medical background and the minimally invasive surgical specialist in much the same way as vascular interventionalists have evolved.

All current and future developments will need to be underpinned not only by data but by strong clinical teams and processes to optimize decision making and treatment delivery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:270–297.

- Langman G, Loughrey M, Shepherd N, et al. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain & Ireland (ACPGBI): Guidelines for the Management of Cancer of the Colon, Rectum and Anus (2017) – Pathology Standards and Datasets. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:75–81.

- Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, et al. JGES guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:417–434.

- Vaughan-Shaw PG, Wheeler JM, Borley NR. The impact of a dedicated multidisciplinary team on the management of early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:704–709.

- Rutter MD, Chattree A, Barbour JA, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctologists of Great Britain and Ireland guidelines for the management of large non-pedunculated colorectal polyps. Gut. 2015;64:1847–1873.

- Williams JG, Pullan RD, Hill J, et al. Management of the malignant colorectal polyp: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1–38.

- Lee TJW, Rees CJ, Nickerson C, et al. Management of complex colonic polyps in the English bowel cancer screening programme. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1633–1639.

- Kobayashi N, Yoshitake N, Hirahara Y, et al. Matched case control study comparing endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for colorectal tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:728–733.

- Repici A, Hassan C, De Paula Pessoa D, et al. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review. Endoscopy. 2012;44:37–150.

- Darwood RJ, Wheeler JM, Borley NR. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is a safe and reliable technique even for complex rectal lesions. Br J Surg. 2008;95:915–918.