Abstract

Background: Rectal tumor treatment strategies are individually tailored based on tumor stage, and yield different rates of posttreatment morbidity, mortality, and local recurrence. Therefore, the accuracy of pretreatment staging is highly important. Here we investigated the accuracy of staging by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) in a clinical setting.

Material and methods: A total of 500 patients were examined at the rectal cancer outpatient clinic at Haukeland University Hospital between October 2014 and January 2018. This study included only cases in which the resection specimen had a histopathological staging of adenoma or early rectal cancer (pT1–pT2). Patients with previous pelvic surgery or preoperative radiotherapy were excluded. The 145 analyzed patients were preoperatively examined via biopsy (n = 132), digital rectal examination (n = 77), rigid rectoscopy (n = 127), ERUS (n = 104), real-time elastography (n = 96), and MRI (n = 84).

Results: ERUS distinguished between adenomas and early rectal cancer with 88% accuracy (95% CI: 0.68–0.96), while MRI achieved 75% accuracy (95% CI: 0.54–0.88). ERUS tended to overstage T1 tumors as T2–T3 (16/24). MRI overstaged most adenomas to T1–T2 tumors (18/22). Neither ERUS nor MRI distinguished between T1 and T2 tumors.

Conclusions: In a clinical setting, ERUS differentiated between benign and malignant tumors with high accuracy. The present findings support previous reports that ERUS and MRI have low accuracy for T-staging of early rectal cancer. We recommend that MRI be routinely combined with ERUS for the clinical examination of rectal tumors, since MRI consistently overstaged adenomas as cancer. In adenomas, MRI had no additional benefit for preoperative staging.

Introduction

A wide range of surgical strategies are available for rectal tumor treatment. Local resection methods include endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and transanal endoscopic resection (TEM), whereas major resection strategies include low anterior resection (LAR), combined transanal and abdominal mesorectal excision (TaTME), or abdomino perineal resection (APR) with permanent stoma. Treatment strategy selection is based on the preoperative staging of the tumor, and local resection is only recommended as definite treatment for adenomas and superficial T1 sm1 cancers [Citation1]. Compared to local resection, LAR is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Notably, at 1 year after LAR, up to 46% of patients suffer from major low anterior resection syndrome (LARS), compromising quality of life [Citation2]. Thus, accurate T-staging is necessary to avoid both overtreatment and undertreatment [Citation3].

For early rectal cancer, endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) is the preferred staging method. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) cannot be used to differentiate adenomas from early cancers [Citation4]. Biopsy analysis tends to lead to the understaging of malignant tumors as benign [Citation5]. Studies from dedicated centers reveal that ERUS staging of early rectal cancer has an accuracy rate of up to 89% [Citation6]; however, studies based on multicentre data from clinical practice report accuracy rates as low as 55% [Citation7,Citation8]. One recent investigation demonstrated that staging accuracy was improved when ERUS was combined with real-time elastography (RTE), in which tumor tissue stiffness is evaluated to predict malignancy [Citation9].

In the present study, we aimed to compare the accuracy of T-staging by MRI and ERUS for adenomas and early rectal cancers in a clinical setting.

Material and methods

Patients

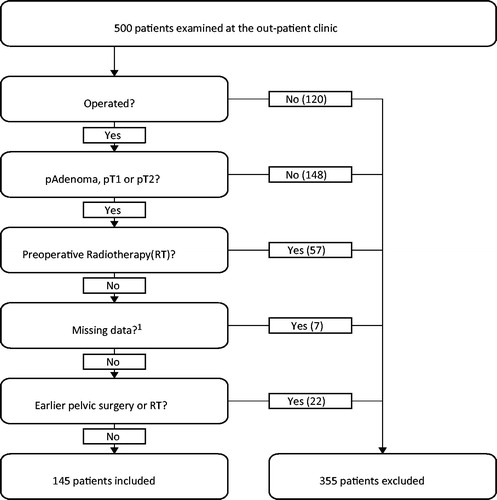

For this study, we prospectively and consecutively recruited the 500 patients with a suspected rectal tumor who were referred to the rectal cancer outpatient clinic of the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway, between October 2014 and January 2018. Of these 500 patients, 120 were excluded because they were ineligible for surgical treatment for multiple reasons (no visible tumor, frailty, or complete response after radiotherapy). We analyzed only early rectal cancers and adenomas (defined as pT1 and pT2 cancers), and thus excluded all histologically verified pT3 and pT4 tumors. After additionally excluding the patients who received preoperative radiotherapy or had undergone earlier pelvic surgery or radiotherapy, 145 patients remained eligible. shows the flowchart, and presents the patient characteristics.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing the patient inclusion and exclusion. 1Inconclusive/no findings with both ERUS and MRI, for example, patient with pacemaker and tumor beyond the reach of the ultrasound probe.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

All clinical examination results were prospectively recorded on a special form, and stored in a database. Our analyses were performed using data from these forms, and information from the electronic patient chart.

Clinical examination

Each consultation at the outpatient clinic began with a digital rectal exploration (DRE), followed by an airless rigid rectoscopy. These examinations were used to determine the tumor’s distance from the anal verge and localization at the rectal wall. The investigators recorded their findings regarding tumor size and morphology, and categorized the tumor as benign, malignant, or inconclusive. A final rigid rectoscopy with air was performed after the ultrasound examination.

ERUS and RTE

After the initial clinical examination, patients were examined by ultrasound and strain elastography. These examinations were performed by a total of seven different operators with varying degrees of experience; however, 72% of examinations were performed by one experienced clinician. The ultrasound equipment used was a standard scanner with elastography software (Hitachi EUB-8500, software version V16-04A; Hitachi Medical Corporation, Kashiva, Japan). Both the endoscopic ultrasound examination and RTE were performed using a rigid 360° ultrasound probe (Hitachi EUP-R54AW-19) with a micro convex array probe (5–10 MHz).

From the ERUS, we determined the T- and N-stage and recorded the overall impression of the tumor as benign, malignant, or inconclusive. In cases where the clinician could not distinguish between T-stages (e.g., T2/T3), the highest stage was recorded in the database.

While ultrasound revealed the degree of tumor infiltration, elastography provided information regarding the tumor tissue stiffness (strain). The elastography software adds a layer of color to the B-mode ultrasound image, such that soft and hard tissues are differently colored. A reproducible elastogram can be achieved by applying pulsatile pressure to the tumor using a water-filled balloon connected to a syringe. The examiner compared the elastogram of tumor tissue with that of the surrounding normal tissue to obtain a strain ratio (SR). An SR of <0.8 indicated a benign lesion, and >1.6 a malignant lesion. The method has been described in greater detail in our previous article [Citation5]. The results are reported as the median SR of 5 measurements, and categorized as benign, malignant, or inconclusive.

MRI and histopathology

Since 2015, almost all magnetic resonance scans have been performed using a 3T Siemens Prisma (Trademark Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). In the few exceptions, MRI was performed using a 3T Siemens Skyra or a 1.5T Siemens machine. The MRI protocol included transversal, sagittal, and coronal T2-weighted turbo spin echo sequences, as well as a high-resolution T2-weighted series angled perpendicular and parallel to the long axis of the rectal lesion [Citation10,Citation11]. The acquired images were examined by a radiologist, who commented on them and set a tentative T-stage for the tumor. If the radiologist considered two stages of infiltration to be equally probable (e.g., T1/T2), the higher stage was chosen and recorded in the database. During the study period, the MRIs were interpreted by 10 radiologists with varying degrees of experience.

Biopsies were obtained during colonoscopy or rectoscopy. Biopsy results were recorded as either adenocarcinoma, adenoma, or inconclusive.

EMR material was formalin-fixed and sent to the department of pathology. Specimens from transanal endoscopic microsurgery were pinned on a plate before fixation, and sectioned at intervals of 2–3 mm, followed by investigation of the whole specimen. The specimens from rectal resections were sectioned at intervals of 3–4 mm, and only representative sections were selected for microscopy. The tissue samples were stained with hematoxylin–eosin.

We retrospectively obtained the MRI staging, biopsy, and final histopathological results from the electronic patient chart. The outpatient clinic DRE, rectoscopy, ERUS, and RTE results were recorded as benign, malignant, inconclusive, or not performed. Tentative T- and N-stages were determined based on the ERUS and RTE findings.

Statistics

Final tumor histopathology was set as the gold standard reference. For all examination techniques, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy. To compare ERUS to MRI, the data were paired and a Wilson score interval [Citation12] was calculated to determine 95% confidence intervals for the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of each examination.

Ethics

The database creation was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics of Western Norway. This study was part of a surgical quality registry: ‘Surgical treatment of colorectal cancer and other bowel illnesses 2011-6524’.

Results

Patients

The median age of the total patient cohort was 68 years, and was similar among all T-stages. The male/female ratio was 1.64. Of the 145 patients investigated, final histopathological analysis revealed adenomas in 69 patients, and early rectal cancer (pT1 or pT2) in 76 patients. Upon investigation at the outpatient clinic, one-third of the tumors were described as polypoid, another one-third as sessile, whereas the rest were inconclusive or thought to be malignant.

Among the adenomas, ∼94% (n = 65) were treated with EMR, ESD, or transanal endoscopic microsurgery. The remaining four patients (5.8%) were treated by resection without a permanent stoma, and are described in Supplementary Table 1. The early colorectal cancers were treated by transanal endoscopic microsurgery, LAR, or APR. Six of the patients treated by LAR received a permanent stoma.

There were 38 T1 tumors, and sm-substage was available for 32 and unavailable for six. Five T1 tumors were classified as sm1, of which three were resected by TEM and the other two T1sm1 tumors were treated with a LAR. Among the T1sm2 and T1sm3 tumors, ∼50% (14/27) were initially operated by TEM. A total of 19 T1sm2, T1sm3, and T2 tumors were initially operated by TEM, of which 10 were reoperated within 6 weeks. Among these 10 cases, the final histopathological results identified tumor tissue in seven of the specimens. Among the nine cases in which salvage surgery was not performed, postoperative radiotherapy was performed in two. The remaining seven patients without salvage surgery received follow-up examinations by rectoscopy and MRI, in accordance with the patients’ wishes, and one of these patients experienced recurrence by November 2018.

T-stage accuracy

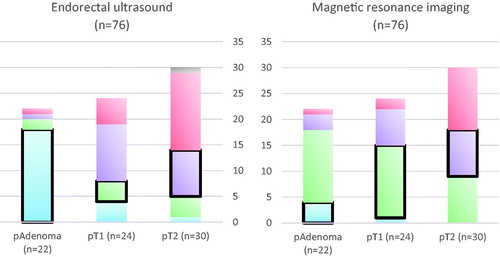

A total of 76 patients were staged by both MRI and ultrasound. presents the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy of both means of examination. presents the rates of understaging and overstaging.

Figure 2. Diagrams showing the T-staging accuracy of ultrasound (left) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (right), based on the 76 patients with conclusive results from both MRI and endorectal ultrasound (ERUS). Correctly staged tumors are marked with a thick line. Colors indicate tentative staging, with blue indicating adenomas, green cT1, purple cT2, red cT3, and gray cT4. ERUS overstaged 4 adenomas (2 T1, 1 T2, and 1 T3), 16 T1 tumors (11 T2 and 5 T3), and 16 T2 tumors (15 T3 and 1 T4). ERUS also understaged 4 T1 tumors and 5 T2 tumors (4 T1, 1 adenoma). MRI overstaged 18 adenomas (14 T1, 3 T2, and 1 T3), 9 T1 tumors (7 T2 and 2 T3) and 12 T2 tumors (12 T3). MRI understaged 1 T1 tumor and 9 T2 tumors (9 T1).

Table 2. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of ERUS and MRI for staging adenomas and pT1 and pT2 rectal cancers, based on the 76 patients with both conclusive MRI and conclusive ERUS.

Clinical examination

Of the 145 patients, 77 had tumors that were classified as either benign or malignant based on DRE (49 inaccessible, 19 inconclusive). Of these 77 tumors, 35 were histologically determined to be malignant, 12 of which had been misinterpreted as benign based on DRE. On the other hand, all 42 benign tumors were correctly identified as benign based on DRE, giving a positive predictive value of 100%.

A total of 104 tumors were staged as either malignant or benign based on rigid rectoscopy (3 not performed, 38 inconclusive). Of the 56 benign tumors, 55 were staged as adenomas. Among the 48 cancers, 13 were understaged as adenomas by rectoscopy.

ERUS and RTE

A total of 127 of the tumors were interpreted as malignant or benign based on ultrasound (7 not performed, 11 inconclusive). Approximately one-third of malignant tumors (20/66) were misinterpreted as benign, whereas 5 of 61 adenomas were wrongly classified as malignant. Among these 127 tumors, only 96 also had conclusive RTE staging (14 inconclusive, 17 not performed). In these 96 cases, 9 of 51 cancers were wrongly classified as adenomas, whereas 6 of the 45 adenomas were classified as cancers. ERUS overstaged pT1 tumors as T2 tumors in 11 of 24 cases.

Based on the summarized results of DRE, ERUS, RTE, and rectoscopy, the most experienced clinician differentiated benign tumors from malignant tumors in 86% of the cases. The remaining six clinicians, as a group, correctly differentiated 81% of the assessed tumors.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Among the study participants, 95 underwent MRI, of which 84 were performed using the most recent MRI protocol (February 2015). Of these 84 patients, 59 had early rectal cancer, whereas 25 had benign rectal tumors. When staged by MRI alone, one cancer was classified as an adenoma, while 21 of the 25 adenomas were overstaged as cancers. With regard to the staging of T1 tumors, MRI achieved a higher sensitivity than ERUS. However, the total accuracy of MRI was lower due to the low specificity.

Biopsy

Biopsies were obtained from 132 of the 145 tumors (13 not performed, 0 inconclusive). Pathologists diagnosed adenocarcinomas in 53 of the 71 cancers, meaning that 18 malignant tumors were understaged as benign.

The clinician performing the majority of ERUS examinations (94/127) in this study was blind to biopsy results during all of his examinations. The biopsy results were available to the other examiners in 20 of the remaining 33 ERUS examinations. The biopsy results were available to the radiologist interpreting the MRI scans in 71 of the 84 cases.

Overall findings

summarizes the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy for separating benign and malignant lesions using all examination techniques.

Table 3. Summary of the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of the different means of preoperative examination.

Discussion

For rectal adenomas and early rectal cancers, the available treatment options range from local excision to formal resection. Importantly, formal resection compromises quality of life due to greater rates of morbidity and LARS [Citation2] or permanent stoma, particularly in cases of low rectal tumors. Meticulous and reliable diagnosis is necessary to determine the best treatment option. In the present study, we aimed to evaluate preoperative diagnostic methods in a clinical setting. We examined patients referred to a dedicated outpatient clinic at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway. Based on the clinical relevance and difficulty in distinguishing between adenomas and early rectal cancer, we chose to exclude all pT3 and pT4 tumors. We suspected that our exclusion of T3 and T4 tumors would yield inferior results compared to previously published data [Citation9,Citation13,Citation14]. We also excluded patients who underwent preoperative radiochemotherapy, to eliminate the effects of preoperative treatment. Thus, a strength of this study is the homogenous patient group, including a relatively high number of cases of rectal adenomas or early rectal cancer, examined under highly standardized conditions.

Due to the clinical setting, the examinations were performed by multiple physicians, and interobserver variability could not be eliminated. This is an important factor to consider when interpreting the present results. It is possible that the interobserver variability was larger for the MRI scan interpretation since the clinical examination and ERUS were mostly performed by the same clinician. Both ERUS and MRI interpretations are demanding and have a learning curve [Citation15].

The majority of patients underwent colonoscopy and biopsy performed by a private gastroenterologist. At the dedicated outpatient clinic, patients underwent a DRE and airless rectoscopy, followed by ERUS, RTE, and final rigid rectoscopy. After these examinations, MRI was requested in cases of ambiguous ERUS or suspected malignancy. MRI was not performed in all patients due to the observed tendency of overstaging adenomas. Patients with pacemakers or claustrophobia could not undergo MRI. ERUS was not performed in patients with pain upon rectal examination. This variation in the patients’ diagnostic paths led to the selection of tumors with presumed higher malignant potential for further investigation by MRI. This is an important bias to consider, which may explain some of the overstaging by MRI.

Another potential bias in this study is introduced by the fact that the previous examination results were available in the electronic patient chart during subsequent examinations. If the chart indicates biopsy-proven adenocarcinoma, it is unlikely that the clinician will stage the tumor as benign. While blinding would improve the strength of a prospective study, this bias in this situation reflects the daily clinical practice.

In our clinical setting, ERUS and RTE differentiated between benign and malignant tumors with an accuracy of 88%. MRI had a lower accuracy of 75%, and yielded a considerable number of false-positive benign lesions. These MRI results are in line with our previous published findings that MRI overstaged most benign lesions as malignant [Citation9]. Neither ultrasound nor MRI were reliable for the staging of T1 or T2 tumors. This may partly explain why ∼50% of T1sm2–3 tumors and 5 T2 tumors were initially treated by TEM. However, 96% of patients with an adenoma were treated with local resection and none received a permanent stoma.

Using biopsy results to differentiate adenomas and early rectal cancer led to understaging of ∼30% of the cancers. This finding is in line with earlier studies. Digital examination and rectoscopy also understaged 25–35% of tumors as benign, and ERUS misinterpreted approximately one-third of malignant tumors. These results highlight the potential of understaging and undertreating colorectal cancer. In our study, the use of ERUS as an isolated examination achieved a total sensitivity of only 70% (); however, the clinician only makes a final determination after completion of all the examinations at the outpatient clinic. Within the subgroup of 76 patients shown in , malignant and benign tumors were differentiated with 88% accuracy, providing reason to believe that RTE and rectoscopy reduced the risk of understaging cancer.

Our results provide grounds for questioning the impact of MRI investigation in patients staged as benign, and support that MRI could be omitted for patients with suspected adenoma and unambiguous clinical examination and ERUS. One such case is described in ; patient 1 was overstaged by imaging, which led to overtreatment. Similarly, Lee et al. also observed that MRI had low accuracy for the staging of clinically benign lesions [Citation16]. However, the ERUS results presented in their study are inferior to the results achieved at our outpatient clinic. They also report that MRI led to understaging of malignant lesions, in contrast to the overstaging found in our study. This raises important questions regarding the role of preoperative imaging in cases of clinically benign lesions. In contrast to the poor ERUS results reported by Lee et al., we think that ERUS adds valuable diagnostic information. In our setting, ERUS is part of the clinical examination and takes an additional 5–10 min. We cannot distinguish between ERUS and the rest of the clinical examination, as ERUS is performed taking into account all previously acquired information.

When making treatment decisions, one must consider the best available diagnosis, as well as the patient’s general status and expectations from treatment. Information about the patient’s general condition, habitus, tumor relation to the sphincter, and sphincter quality will be available. Due to the unsatisfactory results of T-staging, formal resection should be preferred, especially in younger patients with higher tumor location and suspected rectal cancer. When local excision is considered, ESD might be the better option to facilitate potential reoperation. In elderly and frailer patients, it may be prudent to choose organ-sparing treatment despite the increased risk of local recurrence.

Our results are in agreement with previously published data regarding the challenges of accurately staging early stage rectal tumors, both with regard to ERUS and MRI. The implications of both overtreatment and undertreatment of rectal tumors warrant a multi-modal approach to pretreatment evaluation, and subsequent discussion of all patients in a multidisciplinary team setting. The final treatment decision should be made after providing the patient with sufficient information, and with consideration of the patient’s preferences. A clinical examination including ERUS can distinguish adenomas from early cancers with high accuracy, and can therefore be recommended as part of the presurgical examination in a dedicated outpatient clinic. MRI adds no additional safety to preoperative staging in cases considered to be adenomas.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Morino M, Risio M, Bach S, et al. Early rectal cancer: the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) clinical consensus conference. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:755–773.

- Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255:922–928.

- Damin DC, Lazzaron AR. Evolving treatment strategies for colorectal cancer: a critical review of current therapeutic options. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:877–887.

- Glynne-Jones R, Wyrwicz L, Tiret E, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv22–iv40.

- Waage JE, Havre RF, Odegaard S, et al. Endorectal elastography in the evaluation of rectal tumours. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1130–1137.

- Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, et al. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:38–42.

- Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:821–826.

- Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, et al. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1384–1389.

- Waage JE, Leh S, Rosler C, et al. Endorectal ultrasonography, strain elastography and MRI differentiation of rectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:124–131.

- Wale A, Brown G. A practical review of the performance and interpretation of staging magnetic resonance imaging for rectal cancer. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;23:213–223.

- Brown G, Daniels IR, Richardson C, et al. Techniques and trouble-shooting in high spatial resolution thin slice MRI for rectal cancer. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:245–251.

- Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc. 1927;22:209–212.

- Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, et al. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging-a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232:773–783.

- Patel RK, Sayers AE, Kumar P, et al. The role of endorectal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the management of early rectal lesions in a tertiary center. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2014;13:245–250.

- Surace A, Ferrarese A, Gentile V, et al. Learning curve for endorectal ultrasound in young and elderly: lights and shades. Open Med. 2016;11:418–425.

- Lee L, Arbel L, Albert MR, et al. Radiologic evaluation of clinically benign rectal neoplasms may not be necessary before local excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:1163–1169.