Abstract

Background: The standard investigation in colorectal cancer screening (optical colonoscopy [OC]) has a less invasive alternative with the colon capsule endoscopy (CCE). The experiences of screening individuals are needed to support a decision aid (DA) and to provide a patient view in future health technology assessments (HTA). We aimed to explore the experiences of CCE at home and OC in an outpatient clinic by screening participants who experienced both investigations on the same bowel preparation.

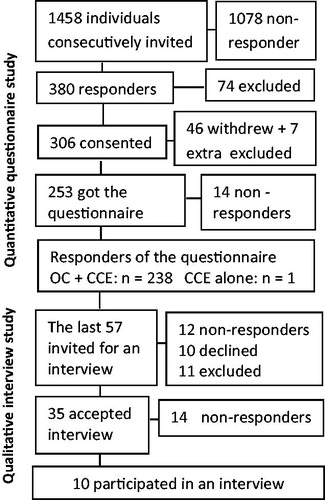

Methods: In a mixed methods study, Danish screening individuals with a positive immunological fecal occult blood test (FIT) were consecutively included and underwent both CCE and OC in the same bowel preparation. They answered questionnaires about discomfort during CCE, delivered at home, and during a following OC in the outpatient clinic. Data were calculated in percentages and Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for comparisons. Among the 253 included patients, 10 participants were selected for a semi-structured interview about their experiences of the two examinations. The analysis and interpretation of the transcribed data were inspired by Ricoeur.

Results: Questionnaire data were received from 239 participants and revealed significant less discomfort during the CCE than the OC. Interview data included explained discomfort elements in two categories: ‘The examination’ and ‘The setting’. Compared to OC, the CCE was experienced with less pain, embarrassment and invasiveness, but presented challenges and disadvantages as well, i.e., a large camera capsule to swallow, a longer waiting time for test results after CCE and an additional OC, if pathologies were found. The home setting for CCE delivery made the participants feel less like they were ill or patients less restricted and that they received more personal care, but could induce technical challenges.

Conclusion: In screening individuals, CCE at home was associated with significantly less discomfort compared to OC at a hospital, and multiple reasons for this was identified.

Background

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is an upcoming new technology [Citation1–3], which is being tested for efficacy as an alternative to conventional optical colonoscopy (OC) [Citation2,Citation4], in individuals with immunological fecal occult blood test (FIT), who participate in a colorectal cancer screening program. OC may be experienced as distressing, humiliating and painful, but has the capability of obtaining biopsies or excision of neoplastic lesions [Citation5]. Individuals’ overall discomfort of CCE is reported [Citation6]. A more comprehensive patient evaluation is warranted.

CCE is an examination of the colon and rectum with a camera capsule, during which the person wears a receiver in a belt around the belly [Citation4]. The camera capsule is swallowed and takes multiple pictures, while the capsule passes through the intestine and transmits the recordings to the receiver for further analysis and interpretation. If the camera capsule identifies neoplasms, an additional OC is needed for biopsy or excision. The CCE requires a similar bowel preparation as for OC. An advantage of the CCE is the possibility to perform the investigation in the patients’ home [Citation4]. Former individuals’ experiences can be of value to future patients, especially if they have a choice between methods [Citation7], as is the case in colorectal examination [Citation2,Citation6,Citation8–12]. Moreover, new technologies optimally go through an assessment in order to guide politicians and clinical practice, and such a comprehensive health technology assessment (HTA) contains benefits and harms including patient-based evidence [Citation13]. We aimed to explore screening individuals’ experiences of a CCE at home and a following OC at a hospital outpatient clinic.

Methods

A mixed methods design was chosen in order to obtain as comprehensive knowledge as possible. Within a cohort study where patients had both CCE and OC, we had a large-scale case-control study, where the participants served as their own control. They were consecutively invited to answer a questionnaire containing few selected questions, where we attempted to reach generalizability. In a minor group of our case-control study, we supplemented by a phenomenological-hermeneutical oriented interview study, where deep data from a few participants could help us gain insight into what might be the causes for answers achieved from our entire study population [Citation14,Citation15]. Important elements of OC experiences are pain and embarrassment and, therefore, we had chosen a single question of experienced discomfort in regard to CCE and OC, respectively, for the quantitative approach. This question could be answered in a numerical rating scale ranging from 1 to 10 and anchored by two verbal descriptions of the symptom extreme. For the qualitative approach, we had chosen semi-structured single interviews supported by a pilot tested interview guide with specified questions followed by prompts. The interview guide had the questions: Will you tell me about your experiences regarding CCE and OC? What contributed to your experience of safety/uncertainty? And would you please elaborate?

Participants

Participants were individuals from the Danish screening population (aged 50–74), who returned a positive immunological FIT and accepted participation in a clinical trial taking the CCE the day before the conventional OC and within the same bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol [Citation4]. Exclusion criteria were known inflammatory bowel disease, an ostomy, diabetes mellitus, cardiac electronic devices, symptoms of bowel obstruction, previous gastrointestinal surgery except for appendectomy and a history of vomiting during the bowel preparation. For the interviews, we consecutively invited the last 57 participants via a written request, which by those interested, could be filled in with a contact phone number and returned at the hospital together with the CCE monitor. The interested participants were thereafter contacted by phone. We decided to exclude participants with more than four months delay between the examinations and the interview, although the CCE and the OC were considered as memorable special emotional events [Citation16].

Procedure and data collection

One of three study nurses instructed the participants in the bowel cleansing and brought the camera capsule and monitoring system to the participants’ homes [Citation4]. She left the home after the equipment gave the first signal announcing that the camera capsule had passed the stomach, which was between 30 and 45 min after she arrived. All participants were left with a checklist with instructions of what to do and what to expect during the examination period, a back-up telephone number for the study nurse, and the questionnaire. After the capsule was excreted, the participants had to dismount the monitoring equipment, store it in accordance to instructions and bring it to the hospital the following day at the appointment for the OC. All OCs were performed at the same endoscopy center by experienced endoscopists. At the hospital, a trained nurse used 20–25 min to prepare the participants for the OC including a discussion of what to expect and she inserted an intravenous access. The OC was performed with magnetic scope guides and carbon dioxide for insufflation [Citation4]. Before and during the OC, the participants were offered intravenous sedation with 0–50 mg pethidine and 0–5 mg midazolam as needed. After a 30-min recovery period in the observation room (together with up to eight other patients), the participants completed the questionnaire. Semi-structured interviews were done by a female study nurse (author CP), who made all arrangements with the participants and who presented herself as a dedicated study nurse working in a new field. The study nurse was experienced in patient contact and had undergone a training course in interview techniques, including practical tests and she did all interviews under supervision of the first author, who is an authorized and experienced interviewer. All interviews (one per participant) were done by phone, audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data handling

Data from the numerical rating scale was double entered in order to minimize entering errors, and divided into groups of <4 (low level of discomfort), 4–6 (moderate level of discomfort) and >6 (high level of discomfort). We performed calculations in percentages and compared the results between CCE and OC using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. A p value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were handled through text analysis in two of three steps inspired by Ricoeur and Pedersen [Citation17,18]. The first step was a naïve reading, where the text was read and an overall conservative interpretation was made. In the second step, a structural analysis was performed converting what is said to what is talked about and followed by categorizing in themes. These two steps were repeated and adjustments were made until the structural analysis validated the overall interpretation. All coding was done by the third author using Microsoft Word marking, but discussed with the first author and adjusted until agreement.

Ethical considerations

All participants received oral and written information about the purpose of the study, their rights, and for the large-scale study part also information about the two examinations, before they signed consent forms. This study was registered in Clinical Trials.gov and approved by the local ethics committee and the Danish data protection agency.

Results

Between May 2015 and February 2016, 1458 individuals were consecutively invited and 306 were eligible for the quantitative study part (). Of these, 46 withdrew and seven were excluded due to vomiting, including one who could not swallow the camera capsule. A total of 253 consented to participate and received the questionnaire. Of these, 239 participants fully or partly answered the questionnaire and 14 did not, which we regarded as missing at random. Of the last 57 participants, 35 initially accepted an interview. Of these, a signed consent form was received from 10 participants, who all participated in an interview with a duration of 20–40 min. Participant baseline characteristics are summarized in , revealing an equal distribution between gender and age in the questionnaire study. Among the interviewed, we have equal representation of educational level and age, but were not able to include younger females, i.e., between 50 and 65 years of age (). None of the interviewed was diagnosed with cancer. Data from non-participants was not obtainable. The overall discomfort is presented in together with the question asked and the response rates. This demonstrates 89% participants with medium to high discomfort in OC, 7% with medium to high discomfort in CCE and a mean discomfort rating difference of three units in favor of CCE (p < .0001). All ten interviewed participants elaborated upon their experiences and we reached qualitative data saturation at interview number six of the ten. In the qualitative analysis and interpretation, the naïve reading revealed differences regarding advantages and disadvantages during OC and CCE, and in the structural analysis two distinct areas of advantages and disadvantages of the OC and CCE emerged: ‘The examination’ and ‘The place’. The examination theme contained the issues: pain, embarrassment, invasiveness and for the CCE also technical induced waiting time and the risk of having an OC. In short, all disadvantages in the OC were turned to advantages in the CCE and vice versa, and additional disadvantages in the CCE were disclosed. This was mirrored in the second theme: ‘The place’ where the home setting offered experiences of feeling less like being ill, less restricted and receiving more personal care, but presented technical challenges. These results represent possible ways to experience the different examinations regarding elements of more or less discomfort and are presented in . A central part of the structural analysis is available in the supplementary file.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants.

Table 2. Questions and numbers asked response rates and distribution of overall discomfort.

Table 3. Possible advantages and disadvantages of the CCE and OC.

Discussion

Screening individuals experienced significantly less discomfort from CCE than OC, which, together with our uncovered compared meaningful elements of advantages and disadvantages from a patient’s view, adds important new knowledge regarding these colorectal procedures.

Our screening participants rated their overall experienced discomfort significantly higher during OC than during CCE, even though they were offered intravenous sedation and analgesia during OC. This is supported by others, but the strength of our study is the large sample size and that all patients experienced both examinations and served as their own control [Citation6,Citation12]. Our study indicates that we must expect nearly 90% of patients with medium to high degree of discomfort in OC and less than 10% with medium to high discomfort in CCE, which in the future might contribute to challenging the OC as the preferred primary investigation tool. Our study presents the best evidence to date on overall comparison of patients’ experiences during OC and CCE. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to qualitatively investigate patients’ experiences of CCE in a home setting. We found that the private home settings for CCE might contribute to an experience of being less restricted, feeling less like they were ill, and receiving more personal care, but could challenge the individuals’ technical skills. It is a new trend to be monitored or treated at home, and others report patients’ experience of more independency when monitored at home as compared to the hospital. Moreover, distress regarding risk of technology failure might be a challenge in such situations, indicating a need for support in the use of technical healthcare solutions at home [Citation19], which are found manageable, if their tasks are simple [Citation20]. This supports our findings, that the easily managed equipment at CCE was well managed by participants in spite of initial uncertainty toward the situation. Regarding the comparisons of experiences through CCE and OC, we found the advantages in CCE to include no or minor pain, no embarrassment and less invasiveness. The disadvantages were a need for an additional OC, if therapy was needed, and technical induced waiting time: a long evening, if the capsule had a long transit time and having to wait days for the result of the CCE, which might trigger worrying. These first mentioned advantages and disadvantages were opposite in OC. It is evident that such elements can be disadvantages and advantages in colonoscopy performed without general anesthesia, as reported by both symptomatic patients [Citation6,Citation21,Citation22] and screening individuals [Citation5,Citation23,Citation24], and are recently reported from both qualitative studies, cohort studies and register research [Citation21–28]. They thereby support our findings of a possible distribution of advantages and disadvantages in OC. Pain during OC was described as severe by many of our participants, and others before us report patients comparing such pain with delivery pain, dental drilling pain, migraine or cramping in muscles or stomach [Citation29]. Moreover, as we found more than 12 times as many individuals experiencing medium to high discomfort in OC compared to discomfort in CCE, it might be tempting to interpret that pain is of special importance in individuals’ rating of discomfort. However, we are not able to make such a conclusion. All identified elements of advantages and disadvantages gave meaning to the experiences of discomfort through the two examinations. Our findings add useful knowledge for a HTA and development of a new decision aid (DA) for clinical practice. Such works might soon be requested from healthcare leaders and clinical practice, as a recent systematic review and meta-analysis report that individuals preferred OC due to a higher detection rate compared to CCE [Citation2], but more recent studies report the opposite trend [Citation4,Citation6]. Further research on how symptomatic patients experience CCE and OC are needed and should include the clinical hospital setting with deep propofol sedation during OC. Screening individuals seem to have a high satisfaction with this [Citation30], and also higher than individuals in moderate sedation [Citation31], which our participants received during the OC.

Limitations

It may be argued that our participants from the large study rated discomfort in OC higher than in CCE as they had the experience of OC more readily available at the rating time. It can also be speculated that our participants rated the OC with less discomfort than actually experienced, because they, at the rating time, might be affected by the sedation received at the OC. However, patient scores of discomfort after colon examination with sedation are by others found not to differ, whether it was measured at the day of examination or one day later [Citation32], and by collecting scores before patients left the hospital, we reached a response rate of 94.5%. A failure to recall events four months ago might be suspected in the interview data, but all the interviewees could call the screening events to mind, which corresponds well to findings that our memory is more readily available when events are connected to positive or negative emotions [Citation16]. A treatment for cancer would have been a more traumatizing event, which might shadow other memories, but this was not the case in our interview participants. Moreover, their experiences did fit very well in the overall quantitative rating made by our larger group of 239 participants short after their OC, which increases the credibility. Our inclusion and exclusion criteria might have selected the bravest of those in good physical and mental shape entering screening, and we did not succeed in interviewing any young female (age 50–65 years), but within the number of interviewees we reached data saturation. Our quantitative results can be generalized to screening sessions in western cultures. The qualitative results cannot be generalized, but transferred to similar settings.

Conclusion

Screening individuals investigated by home-delivered CCE have significant less discomfort compared to OC performed at the hospital. Elements of discomfort might include pain, embarrassment, invasiveness, technical induced waiting time and lack of technical skills, and moreover, to be more restricted and feeling more like being ill and receive less personal care at the hospital.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants for their support to this study and acknowledge Jane Holt and Vibeke Baatrup for entering the data.

Disclosure statement

All authors have contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, and/or the analysis and interpretation of data. The first author drafted the manuscript and all coauthors have revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have approved the final article. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Medtronic delivered free camera capsules, but they had no influence on the research or publishing.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Friedel D, Modayil R, Stavropoulos S. Colon capsule endoscopy: review and perspectives. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:1.

- Spada C, Pasha SF, Gross SA, et al. Accuracy of first- and second-generation colon capsules in endoscopic detection of colorectal polyps: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1533–1543.e8.

- Scallan R. State of the art inside view, the camera pill. Technol Health Care. 2016;24:471–481.

- Kobaek-Larsen M, Kroijer R, Dyrvig AK, et al. Back-to-back colon capsule endoscopy and optical colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening individuals. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20:479–485.

- McLachlan SA, Clements A, Austoker J. Patients’ experiences and reported barriers to colonoscopy in the screening context-a systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:137–146.

- Ojidu H, Palmer H, Lewandowski J, et al. Patient tolerance and acceptance of different colonic imaging modalities: an observational cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:520–525.

- Bennett KF, von Wagner C, Robb KA. Supplementing factual information with patient narratives in the cancer screening context: a qualitative study of acceptability and preferences. Health Expect. 2015;18:2032–2041.

- Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:761–769.

- Miller DP, Jr., Denizard-Thompson N, Weaver KE, et al. Effect of a digital health intervention on receipt of colorectal cancer screening in vulnerable patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:550–557.

- Imaeda A, Bender D, Fraenkel L. What is most important to patients when deciding about colorectal screening? J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:688–693.

- Rex DK, Lieberman DA. A survey of potential adherence to capsule colonoscopy in patients who have accepted or declined conventional colonoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:691–695.

- Adrian-de-Ganzo Z, Alarcon-Fernandez O, Ramos L, et al. Uptake of colon capsule endoscopy vs. colonoscopy for screening relatives of patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:2293–2301.e1.

- Swedish Council on Health Technology A. SBU methods resources. Assessment of methods in health care: a handbook. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU), Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment; 2016.

- Bowling A. Research methods in health. Investigating health and health services. 2nd ed. Maidenhead, Philadelphia (PA): Open University Press; 2002.

- Kvale SB. Interviews–learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2nd ed. London: Saga Publications Inc.; 2009.

- Hamann S. Cognitive and neural mechanisms of emotional memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:394–400.

- Ricoeur P. Interpretation theory. Fort Worth (TX): The Texas Christian University Press; 1979.

- Pedersen BD. Sygeplejepraksis, sprog & erkendelse [nursing practice, language & cognition]. Århus, Denmark: Fællestrykkeriet for Sundhedsvidenskab og Humaniora; 1999.

- Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, et al. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e52.

- Lind L, Karlsson D. Telehealth for “the digital illiterate”–elderly heart failure patients experiences. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;205:353–357.

- Hafeez R, Wagner CV, Smith S, et al. Patient experiences of MR colonography and colonoscopy: a qualitative study. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:765–769.

- von Wagner C, Ghanouni A, Halligan S, et al. Patient acceptability and psychologic consequences of CT colonography compared with those of colonoscopy: results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial of symptomatic patients. Radiology. 2012;263:723–731.

- Ghanouni A, Plumb A, Hewitson P, et al. Patients’ experience of colonoscopy in the English bowel cancer screening programme. Endoscopy. 2016;48:232–240.

- de Jonge V, Sint Nicolaas J, Lalor EA, et al. A prospective audit of patient experiences in colonoscopy using the global rating scale: a cohort of 1,187 patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:607–613.

- Akerkar GA, Yee J, Hung R, et al. Patient experience and preferences toward colon cancer screening: a comparison of virtual colonoscopy and conventional colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:310–315.

- Mikocka-Walus AA, Moulds LG, Rollbusch N, et al. “It’s a tube up your bottom; it makes people nervous”: the experience of anxiety in initial colonoscopy patients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2012;35:392–401.

- Ristvedt SL, McFarland EG, Weinstock LB, et al. Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy, and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:578–585.

- Teoh W-CA S, McDonald J. PillCam colon capsule endoscopy: the patient’s perspective. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:1.

- Ylinen ER, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K, Pietilä AM. Effects of patients’ anxiety, previous pain experience and non-drug interventions on the pain experience during colonoscopy. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1937–1944.

- Turk HS, Aydogmus M, Unsal O, et al. Sedation-analgesia in elective colonoscopy: propofol-fentanyl versus propofol-alfentanil. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2013;63:352–357.

- Eberl S, Polderman JA, Preckel B, et al. Is “really conscious” sedation with solely an opioid an alternative to every day used sedation regimes for colonoscopies in a teaching hospital? Midazolam/fentanyl, propofol/alfentanil, or alfentanil only for colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:745–752.

- Brooks AJ, Hurlstone DP, Fotheringham J, et al. Information required to provide informed consent for endoscopy: an observational study of patients’ expectations. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1136–1139.