Abstract

Background: Patients with certain autoimmune diseases (AID) have an increased risk of developing diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). However, the occurrence of AID in patients with DLBCL as well as the impact of AID on outcome has not been extensively studied. The main purpose of this study was to establish the occurrence of AIDs in a population-based cohort of DLBCL patients and to compare outcomes in patients with or without AID treated with rituximab(R)-CHOP/CHOP-like treatment. We also aimed to analyse gender differences and the potential role of different AIDs on outcome and the frequency of treatment-associated neutropenic fever.

Patients and methods: All adult patients treated 2000–2013 with R-CHOP/CHOP-like treatment for DLBCL in four counties of Sweden were included (n = 612). Lymphoma characteristics, outcome and the presence of AID were obtained through medical records.

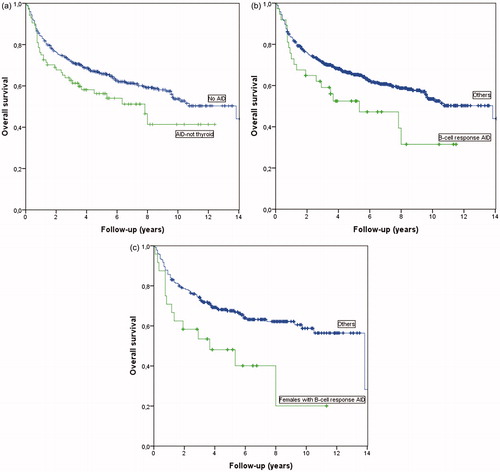

Results: The number of patients with AID was 106 (17.3%). Thyroid disease dominated (n = 33, 31.1%) followed by rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n = 24, 22.6%). The proportion of AID was significantly higher in females (59/254, 23.2%) vs. in males (47/358, 13.1%) (p = .001). In the whole cohort there was no difference in event free survival (EFS) or overall survival (OS) between patients with or without AID. However, patients with an AID primarily mediated by B-cell responses (thyroid disorders excluded) had a worse OS (p = .037), which seemed to affect only women. The AID group more often had neutropenic fever after first treatment (16.0% vs 8.7%, p = .034) and those with neutropenic fever had a worse OS (p = .026) in Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Conclusion: There is a high prevalence of AID among patients with DLBCL. AIDs categorized as primarily B-cell mediated (in this study mainly RA, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome) may be associated with inferior OS. AID patients may be more prone to neutropenic fever compared to patients without concomitant AID.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common type of lymphoma, accounts for approximately 40% of all lymphomas [Citation1–3] and is slightly more common in men with a reported male:female ratio of 1.2:1 [Citation2,Citation4]. The cause of DLBCL is unknown, but immune disorders including autoimmune diseases (AID) are known risk factors [Citation5–12].

Autoimmune diseases are a heterogeneous group of more than 80 separate conditions with a prevalence in the general population ranging from ∼3% to 10% in different reports [Citation4,Citation5,Citation13–16]. The risk of lymphoma varies between the different AIDs and has repeatedly been reported to be about 2-fold increase in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 5-fold increase in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and up to 20-fold increase in primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) compared to the general population [Citation6–8,Citation17]. Increased lymphoma risks have also been reported in a number of other AIDs such as thyroiditis, diabetes type 1, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and psoriasis [Citation6–8,Citation17].

Several studies have described an association between AIDs and an increase in DLBCL [Citation11,Citation15,Citation18,Citation19]. The prevalence of AIDs in a DLBCL population remains, however, unclear. Data has been inconsistent between studies and it is not clear if this is an effect of differences in study designs, study population characteristics or the definitions and inclusion criteria that have been used. In some studies, AIDs have been self-reported by patients [Citation20] and/or restricted to predefined AID diagnoses [Citation12,Citation21].

Further, the role of AIDs in DLBCL prognosis is still uncertain. One study, performed before the addition of rituximab (R) as standard treatment for DLBCL, indicated a poor overall survival (OS) in DLBCL patients with RA and widespread lymphoma already at diagnosis and correlation to severe RA disease [Citation22] while another study including patients from the same period found similar OS for DLBCL patients with RA compared to non-RA controls [Citation23]. In another study including patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) 1999–2002 self-reported AID was associated with an increased rate of all-cause death for all NHL combined but not for specific lymphoma subtypes [Citation24]. After the introduction of the anti-CD20 antibody R as a complement to CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) or CHOP-like chemotherapy, the outcome for DLBCL patients, in general, has dramatically improved with increase in OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and event-free survival (EFS) [Citation25–28]. Since R is also used to effectively curb disease progress in some AIDs updated outcome assessments of R-based treatment for AID- related DLBCL is of specific interest.

Some studies of AID-related lymphoma have categorized AIDs as primarily mediated by B-cell responses or by T-cell responses [Citation6,Citation12]. Recent studies have pointed out a correlation between DLBCL and several AIDs categorized as primarily mediated by B-cell responses such as RA, SLE and pSS and have also indicated an association between the group of primarily B-cell mediated AIDs and inferior outcomes [Citation20,Citation21,Citation29].

Gender differences in survival after R-CHOP treatment have been indicated in DLBCL patients in general with women having better survival overall [Citation30,Citation31] or in specific age groups [Citation32,Citation33]. Gender-specific information about AID-related DLBCL is limited. Many of the AIDs are more common in women than in men [Citation4,Citation5,Citation13–16], but studies suggest that the risk of developing lymphoma may be higher in men than women with AID [Citation15]. Whether gender affects the outcome in AID-related DLBCL is not clear.

One clinical problem which potentially may influence prognosis in lymphoma is treatment-related neutropenic fever [Citation34–37]. It is well known that patients with AIDs such as RA and SLE have an increased risk of infections [Citation34,Citation35] and neutropenia may be a manifestation of some of the AIDs [Citation36–38], but it is not known if neutropenic fever is a more common problem in DLBCL patients with a concomitant AID than in DLBCL patients in general.

To increase the knowledge of AID-related DLBCL we investigated the occurrence of all physician-reported autoimmune conditions in a large population-based cohort of DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP/CHOP-like treatment and compared outcomes in patients with and without AID. We specifically analyzed outcomes in AIDs overall and categorized as primarily mediated by B-cell responses or T-cell responses and by gender, and we also evaluated the frequency and outcome of patients with neutropenic fever.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

This was a multi-institutional, retrospective, cohort study of patients diagnosed with DLBCL or subgroups of high-grade malignant B-cell lymphoma between the years 2000 and 2013.

Patient population

Adult patients (>18 years old) resident in four Swedish counties (Uppland, Sörmland, Dalarna, Gävleborg) at the time of lymphoma diagnosis and registered in the Swedish lymphoma registry (INCA; where all newly diagnosed lymphoma cases are registered) with a diagnosis of DLBCL or high-grade malignant B-cell lymphoma who were primarily treated as DLBCL with at least one course of R with either CHOP or CHOEP (CHOP plus etoposide) or mini-CHOP (dose-reduced CHOP) were identified. Patients with primary mediastinal lymphoma and testicular DLBCL were included.

Patients with follicular lymphoma transformed to DLBCL were included in the analysis if the only prior treatment for follicular lymphoma was radiotherapy. We excluded patients with primary central nervous system DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma. Patients considered by the treating physician to be too frail to receive any treatment or treated with less intensive chemotherapy or given other combinations due to comorbidities were excluded.

The study was approved by the local review board (Dnr 2014/233).

Data collection

All clinical data were obtained from medical records from the in-hospital computer-based systems. The following data were recorded: age at lymphoma diagnosis, sex, area of residence, type of lymphoma, date of diagnosis (defined as date of diagnostic biopsy, either needle or surgical), presence of any autoimmune disease at diagnosis, presence of B-symptoms (fever, night sweat, weight loss), performance status (PS 0–4) according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), stage at diagnosis (Ann Arbor 1–4), International prognostic index (IPI 0–5) score, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) above upper limit normal (ULN) or normal, bulky disease (defined as a tumor with a diameter of >7.5 cm), disease in >1 extranodal organ, type of treatment, occurrence of neutropenic fever after first course of treatment, treatment outcome (complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD)), date of relapse, date of death, cause of death, date of last follow-up. The original histopathological diagnoses used in the database were made by the local departments of Pathology in each region using definitions of the 2008 WHO-classification of lymphoma [Citation39].

Definitions

The presence of AID was determined by reviewing the medical charts from the initial visit with the oncologist or haematologist. All available information in the medical charts had to support this diagnosis but it was not confirmed by other means. A patient was considered to have an AID diagnosis in the presence of a medical condition commonly known to be caused by self-reactive antibodies or a disease that results when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's own tissues.

Hypothyroid conditions were included and grouped together as the precise cause of hypothyreosis was not explicitly expressed in the charts for most patients. Four cases of unspecified polyarthritis unconnected to any other AID were grouped with RA. Diabetes mellitus was considered as an AID (type 1 diabetes) if the patient was treated with insulin only.

The treatment outcome was defined as CR, PR, SD or PD based on the disease status at the oncology clinic visit immediately following the end of treatment and was assessed either from clinical and/or radiological findings. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis and last follow up in the absence of relapse. If a relapse occurred, EFS was set to time from diagnosis to date of relapse (date of clinical/radiology finding or biopsy). If the patient never reached CR/PR the EFS time was set to zero. Lymphoma-specific survival (LSS) was defined as the time between initial date of diagnosis and death from lymphoma. Treatment-related deaths were included in LSS. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from diagnosis to date of last follow up or time of death regardless of cause.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median (range) and categorical variables as numbers (%). For bivariate comparisons, the t-test (in case of normally distributed variables) or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test (in case of non-normally distributed variables) was used for continuous variables and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

All time intervals were measured in months. Time-to-event outcomes (EFS, LSS and OS) were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test was used to test statistical significance. A two-sided p-value of ≤.05 was regarded as cut-off for statistically significant results in comparisons between groups. Any variables significantly associated with EFS, LSS or OS in bivariate analyses (with a p-value of ≤.05) were considered for entry into a multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis. Separate multivariate analyses were performed for EFS, LSS and OS, respectively. The analyses were performed by using the complete case analysis approach to handle missing data.

Outcome measures were assessed for all AIDs together, and for the AIDs grouped as primarily mediated by B-cell responses or T-cell responses according to the classification of the InterLymph Consortium (i.e., only the AID diagnoses classified by the InterLymph Consortium were included in the categorization and outcome analyses of B- and T-cell mediated AIDs) [Citation12]. Subgroup analyses were performed with and without the patients with thyroid disease due to uncertainty of AID origin based on the information in the medical records. Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM statistics SPSS version 22.

Results

Study cohort and autoimmune diseases

In total, 612 patients were included in the study. A male predominance was observed with a 1.4:1 male:female ratio (n = 358:n = 254). The number of patients with AID was 106 (17.3%) with the distribution of different AIDs displayed in . Fifteen of the 106 patients had two AIDs (12 females and three males) and one male patient had three AIDs, resulting in totally 122 AID diagnoses in 106 patients.

Table 1. Distribution of 122 different autoimmune disorders in 612 R-CHOP/R-CHOP-like treated patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma divided into autoimmune disorders with primarily B-cell or T-cell responses using the InterLymph classification [Citation12].

Thyroid disease dominated the AID group (n = 33, 31.1%) followed by RA (n = 24, 22.6%). Overall the proportion of AID was significantly higher in females (n = 59 of 254, 23.2%) than in males (n = 47 of 358, 13.1%) (p = .001). Among the more common AIDs (present in ≥10 patients) we observed a female predominance in the frequency of thyroid disease (72.7%) and RA (66.7%), an equal frequency in inflammatory bowel disease and a male overweight in psoriasis (69.2%) () .

Patient characteristics are shown in . Except for gender (p = .001) there were no detectable differences in prognostic factors for DLBCL outcome (age, sex, PS, Stage, IPI, LD > ULN, bulky disease, extranodal engagement >1, treatment, B-symptoms, body mass index (BMI), engagement of kidney/adrenal gland) between the no AID and the AID group. Patients with AID had a higher frequency of febrile neutropenia after the first course of chemotherapy; 16.0% vs. 8.7% (p = .034) compared to those without AID.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of DLBCL patients with and without autoimmune disease.

Outcome

In the whole cohort EFS, LSS and OS at 5 years were 70%, 77% and 69% respectively. In total, 243 (39.7%) patients died during the follow-up period. In 173 cases (71.2%) the cause of death was due to lymphoma or its treatment. Bivariate analysis revealed 5 variables associated with EFS, 5 with LSS and 6 with OS (). When all patients were included in a multivariate analysis with these factors and the presence of AID as a separate factor, there was no significant difference in EFS (HR 1.40, 95% CI: 0.89–2.22, p = .147), LSS (HR 1.46, 95% CI: 0.89–2.38, p = .130) or OS (HR 1.21, 95% CI: 0.79–1.87, p = .378) between patients separated into those with and without AID.

Table 3. Multivariate Cox regression analysis of prognostic factors for event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) in 612 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP-regimens.

Overall survival was also analysed separately for patients with non-thyroid AID compared to the rest of the patients. A Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a borderline worse OS for the non-thyroid AID patients (p = .047) (). However, a multivariate analysis using the same variables as before including non-thyroid AID as a separate factor could not confirm any significant differences in outcome measures between these groups (HR for EFS 1.40, 95% CI: 0.85–2.31, p = .184, HR for LSS 1.58, 95% CI: 0.93–2.68, p = .090, HR for OS 1.43, 95% CI: 0.91–2.27, p = .125).

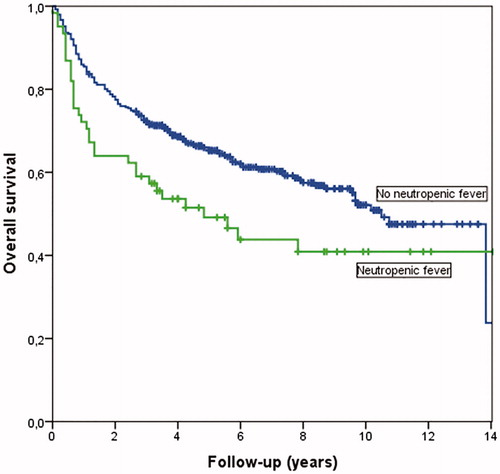

Figure 1. (a) Overall survival by Kaplan Meier comparing DLBCL patients with non-thyroid AIDs vs. all others (p = .047). (b). Overall survival by Kaplan-Meier comparing patients with DLBCL and AIDs with primarily B-cell responses without thyroid disorders vs. all others (p = .037). (c). Overall survival by Kaplan-Meier comparing women with DLBCL and AIDs with primarily B-cell response without thyroid disorders vs. all other women (p = .008).

Outcome in B-cell and T-cell-response AID

Overall survival was analysed separately for B-cell response AIDs, including thyroid disorders, vs. all others with no significant difference (p = .504). We further analysed B-cell response AIDs without the cases with thyroid disorder vs. all others and found a worse OS for this AID group compared to the rest of the patients (p = .037) (). However, in multivariate analysis, no significant difference in OS was detected for B-cell response AIDs without thyroid disorder as a separate factor (HR for OS 1.43, 95% CI: 0.74–2.74, p = .29). There was no significant difference in LSS (HR for LSS 1.42, 95% CI: 0.65–3.08, p = .38 or EFS (HR for EFS 1.17, 95% CI: 0.54–2.54, p = .690) between the groups.

Patients with AIDs primarily mediated by T-cell responses had no significant difference in OS in Kaplan-Meier analysis (p = .244) vs. all others. In a multivariate analysis, these patients had a significantly worse LSS (HR = 2.11, 95% CI 1.09–4.08 p = .028, and EFS (HR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.09–3.63 p = .026) but not OS (HR = 1.71, 95% CI 0.92–3.19, p = .09).

Gender differences

Among all 612 patients in the cohort, OS was similar in men and women (p = .448). However, a separate analysis of the AIDs primarily driven by B-cell responses with thyroid disorders excluded revealed a gender difference. OS was worse for women in this group compared to all other women (, p = .008). In this group of 24 females there were 10 deaths related to lymphoma or its treatment (41.7%), four unrelated deaths and ten patients alive at the end of the follow up period. Cox regression analysis confirmed a worse OS (HR 2.90, 95% CI: 1.25–6.70, p = .013). For the 13 men with B-cell response AID without thyroid disorders OS was similar compared to all other men (p = .819) in Kaplan Meier analysis.

Neutropenic fever

Patients with neutropenic fever after first treatment course had a worse OS in Kaplan–Meier analysis compared with those without neutropenic fever (p = .026), shown in .

Discussion

In this large study of patients with DLBCL and AID in the era of R-based lymphoma treatment we found a higher occurrence of AID, 17.3%, compared to the 3–10% of AID found in the general population [Citation4,Citation5,Citation13–15]. In other studies of AID in DLBCL populations varying figures have been reported [Citation17,Citation18]. In a recent study, and similar to our results, self-reported AID was present in 22.5% of 182 DLBCL patients compared to 13.8% in age- and sex-matched controls without lymphoma [Citation21]. In this study, like in our study, all pre-existing thyroid disorders were included as AID. Other recent studies report lower frequencies. In one study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare-linked database B-cell mediated AID was listed in 4.5% of almost 6000 patients registered with a DLBCL diagnosis at the age of ≥66 years [Citation29]. One study reviewing medical records of 913 newly diagnosed lymphoma patients found AID prior to lymphoma diagnosis in 34 of the patients (3.7%) and of these 18 patients had DLBCL [Citation40]. However, the definition of eligible AID diagnoses is not clear in the last two studies and may be different from the definition we have used. Further, in a prospective cohort study, the frequency of 8 pre-defined AIDs in 736 DLBCL patients was evaluated. Any AID was present in 12.2% of DLBCL patients [Citation20]. In studies by the InterLymph Consortium patient-reported AIDs were present in 5.8% of the included DLBCL patients [Citation12].

One reason for the higher occurrence of AIDs in our study is that we included all pre-existing AID diagnoses reported in the medical records at lymphoma diagnosis. We thereby identified 16 additional diagnoses compared to the patient-reported diagnoses included in studies by the InterLymph Consortium, which further emphasizes earlier notions of a high frequency of different AIDs in a DLBCL population. As in previous studies, the occurrence of AID was higher than reported in general populations both in the women (23.2%) and in the men (13.1%) with DLBCL[Citation5,Citation15].

The most common specific AIDs in this study population are consistent with previous studies. Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE and pSS were the most common AIDs categorised as primarily B-cell mediated (apart from thyroid disorders), and inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis were the most common T-cell mediated AIDs. Thyroid disorders have been handled in different ways in previous studies. As there is some evidence that a majority of thyroid diseases in non-iodine deficient areas are autoimmune [Citation41] we grouped all thyroid disorders together, and instead performed outcome analyses with and without this group of patients.

In the whole cohort, we could not find any significant differences in OS, LSS or EFS between the DLBCL patients with and without AID, and the results remained similar if thyroid disorders were excluded from the analyses. Some differences were suggested when outcome was analysed separately for patients with AIDs categorized as primarily driven by B- or T-cell responses. B-cell response AIDs (with thyroid disorders excluded) were associated with worse OS in Kaplan–Meier analysis and T-cell response AIDs were associated with inferior LSS and EFS in multivariate analysis.

Similar analyses were performed in some of the previously mentioned studies of DLBCL and AID. In the Israeli study including 41 DLBCL cases with AID, a history of B-cell-mediated AIDs was associated with shorter relapse-free survival and OS compared to patients without AID [Citation21]. The prospective study of 8 pre-defined AIDs by Kleinstern et al. reported a non-significant trend toward inferior OS in DLBCL patients with AIDs primarily mediated by B-cell responses, while AIDs primarily mediated by T-cell responses were not associated with OS or EFS in any lymphoma subtype [Citation20]. The authors acknowledge that the number of events in the last group may have been too few to reveal any differences. The study based on SEER-data showed a trend toward deceased lymphoma-related survival in patients with SLE and DLBCL compared to DLBCL patients with other B-cell mediated AIDs [Citation29]. Our study and other previous studies have involved too small numbers of patients with SLE to be able to confirm these findings. The study by Shih et al. reported comparable outcomes in NHL patients (53% had DLBCL) with and without pre-existing AID [Citation40]. This study was based on few cases with DLBCL and AID and reported only outcomes for the whole AID group together.

Previous studies of AID-associated DLBCL have not reported gender-specific information on outcome, but when we analysed OS separately for women and men we found a significant difference. Only women and not men with AIDs primarily driven by B-cell responses (with thyroid disorders excluded) had a significantly worse OS both in Kaplan Meier analysis and multivariate analysis compared to all other women and men, respectively. We cannot explain the reason for the worse OS in women from the analyses possible to perform in this study setting, and e.g., there could be differences in comorbidities and disease severity of the AIDs which we were unable to control for. As the number of investigated cases in this study is limited larger studies addressing gender differences in outcome would be necessary to confirm these findings.

In summary, in the literature, and in this study there is some support for a worse OS associated with AIDs primarily mediated by B-cell responses, mainly driven by women with RA, SLE and pSS in this study. The finding of a worse OS but not LSS may indicate that factors linked to the underlying AID are of importance for the prognosis. This is also in line with the study of Mikuls et al. which showed that RA patients with NHL (43% with DLBCL) had a higher risk of deaths unrelated to lymphoma or its treatment and were more susceptible for coronary artery disease and stroke than non-RA lymphoma controls [Citation23]. Studies have shown that RA patients at increased lymphoma risk are characterized by longstanding, severe RA, factors which are known to predispose to increased mortality and comorbidity per se [Citation42].

The finding of inferior LSS and EFS, but not OS in patients with T-cell response AIDs needs to be further explored in larger studies and has so far no support in the literature.

It should also be noted that the categorization of AIDs primarily driven by B- or T-cell responses is not exact and overlap in immune effector mechanisms exists between the groups which may affect results when using this categorization. The first categorization from the InterLymph Consortium was a result of a rigorous consensus process taking different aspects into account. We, therefore, choose to only include the same categorized AIDs as described by the InterLymph Consortium leaving 16 other identified AID diagnoses outside the outcome analyses.

We found a higher rate of febrile neutropenia after the first treatment course in the AID-group compared to patients without AID, and an inferior OS in those with febrile neutropenia. This has not been reported before in AID-associated DLBCL, and could be one explanation for the worse OS in groups of AID patients, but needs to be further explored in coming studies. Clinicians are well aware of this problem in the care of lymphoma patients in general, and increased awareness of a particular risk in AID patients or groups of AID patients could be a step to improve a potentially inferior outcome in this patient group.

Subtype classification of DLBCLs into germinal centre (GC) B-cell like and activated B-cell (ABC)-like subtypes is also relevant for studies of prognosis in DLBCL as patients with the ABC-subtype in most studies have a worse survival [Citation43–46]. Unfortunately, we did not have this subtype information about the DLBCL cases in this study, which would have been interesting as some studies indicate that the ABC-subtype may be overrepresented in DLBCL patients with RA and SLE [Citation22,Citation47]. It would thus have been of interest to investigate whether the worse OS in patients with primarily B-cell mediated AIDs could be associated with a larger proportion of the ABC-like subtype among these patients.

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. The retrospective design based on data in medical records may result in missed historical data. Although recall bias is avoided with this design, we cannot rule out that some AID diagnoses may have been overlooked or that some patients not fulfil current diagnostic criteria. We grouped all thyroid diseases together as it was often uncertain whether the condition was a consequence of Hashimoto’s disease or not. This may have resulted in the inclusion of patients with non-autoimmune thyroid disorders in the study. Our definition of diabetes type 1 (treatment with insulin only) may have led to erroneous inclusion of some patients with diabetes type 2. Previous treatment of the AIDs was not available in detail and neither was information about duration and severity of the AIDs. We also had limited knowledge of concomitant diseases or lifestyle factors that may affect outcome. Although this is a large study the individual AID diagnoses constitute small groups.

Despite these caveats, the study included a large population-based cohort of DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP/CHOP-like regimens and physician-reported AID and detailed information about the lymphoma disease, and the results might have implications on clinical practice and for future research directions. In patients with DLBCL, as much as up to a quarter of female patients may have a history of AID. Patients with AID may have an increased risk of febrile neutropenia which warrants raised awareness in the clinical care of these patients. Measures to consider could be more frequent use of colony stimulating factors and prophylactic antibiotics in this patient group. Female patients with B-cell response AID seem to have a worse OS and further studies are needed to confirm the results and investigate the background for this potential association. Future studies should consider gender aspects and include detailed data of the underlying AIDs and the specific causes of death to better understand the drivers of prognosis in this patient group. Further studies of DLBCL patients with AID are of specific relevance in the new era of immunotherapy as part of lymphoma treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Erik, Karin och Gösta Selanders stiftelse.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, et al. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019–5032.

- Székely E, Hagberg O, Arnljots K, et al. Improvement in survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in relation to age, gender, International Prognostic Index and extranodal presentation: a population based Swedish Lymphoma Registry study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:1838–1843.

- Smith A, Crouch S, Lax S, et al. Lymphoma incidence, survival and prevalence 2004–2014: sub-type analyses from the UK’s Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1575–1584.

- Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, et al. Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood. 2010;116:3724–3734.

- Cuttner J, Spiera H, Troy K, et al. Autoimmune disease is a risk factor for the development of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1884–1887.

- Ekstrom Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111:4029–4038.

- Smedby KE, Askling J, Mariette X, et al. Autoimmune and inflammatory disorders and risk of malignant lymphomas-an update. J Intern Med. 2008;264:514–527.

- Anderson LA, Gadalla S, Morton LM, et al. Population-based study of autoimmune conditions and the risk of specific lymphoid malignancies. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:398–405.

- Goldin LR, Landgren O. Autoimmunity and lymphomagenesis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1497–1502.

- Vanura K, Späth F, Gleiss A, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of autoimmune diseases and chronic infections in malignant lymphomas at diagnosis. Ann Hematol. 2011;90:947–954.

- Morton LM, Slager SL, Cerhan JR, et al. Etiologic heterogeneity among non-hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: the interlymph non-hodgkin lymphoma subtypes project. JNCI Monogr. 2014;2014:130–144.

- Wang SS, Vajdic CM, Linet MS, et al. Associations of non-hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) risk with autoimmune conditions according to putative NHL loci. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181:406–421.

- Cooper GS, Bynum MLK, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33:197–207.

- Youinou P, Pers J-O, Gershwin ME, et al. Geo-epidemiology and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34:J163–J167.

- Ansell P, Simpson J, Lightfoot T, et al. Non-hodgkin lymphoma and autoimmunity: does gender matter? Int J Cancer. 2011;129:460–466.

- Ngo ST, Steyn FJ, McCombe PA. Gender differences in autoimmune disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:347–369.

- Engels EA, Parsons R, Besson C, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of medical conditions associated with risk of non-hodgkin lymphoma using medicare claims (“MedWAS”). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:1105–1113.

- Cerhan JR, Kricker A, Paltiel O, et al. Medical history, lifestyle, family history, and occupational risk factors for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the interlymph non-hodgkin lymphoma subtypes project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014:15–25.

- Hemminki K, Liu X, Ji J, et al. Origin of B-cell neoplasms in autoimmune disease. PloS One. 2016;11:e0158360.

- Kleinstern G, Maurer MJ, Liebow M, et al. History of autoimmune conditions and lymphoma prognosis. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8:73.

- Kleinstern G, Averbuch M, Abu Seir R, et al. Presence of autoimmune disease affects not only risk but also survival in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2018;36:457–462.

- Baecklund E, Backlin C, Iliadou A, et al. Characteristics of diffuse large B cell lymphomas in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3774–3781.

- Mikuls TR, Endo JO, Puumala SE, et al. Prospective study of survival outcomes in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Jco. 2006;24:1597–1602.

- Simard JF, Baecklund F, Chang ET, et al. Lifestyle factors, autoimmune disease and family history in prognosis of non-hodgkin lymphoma overall and subtypes. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2659–2666.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242.

- Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040–2045.

- Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. Jco. 2005;23:5027–5033.

- Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013–1022.

- Koff JL, Rai A, Flowers CR. Characterizing autoimmune disease-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a SEER-medicare cohort. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:e115–e121.

- Horesh N, Horowitz NA. Does gender matter in non-hodgkin lymphoma? Differences in epidemiology, clinical behavior, and therapy. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2014;5:e0038.

- Sarkozy C, Mounier N, Delmer A, et al. Impact of BMI and gender on outcomes in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP: a pooled study from the LYSA. Lymphoma. 2014;2014:1–12.

- Hedström G, Peterson S, Berglund M, et al. Male gender is an adverse risk factor only in young patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma - a Swedish population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:924–932.

- Pfreundschuh M, Muller C, Zeynalova S, et al. Suboptimal dosing of rituximab in male and female patients with DLBCL. Blood. 2014;123:640–646.

- Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:229.

- Lee YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Overall and cause-specific mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: an updated meta-analysis. Lupus. 2016;25:727–734.

- Gazitt T, Loughran TP. Chronic neutropenia in LGL leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017:181–186.

- Zheng P, Chang X, Lu Q, et al. Cytopenia and autoimmune diseases: a vicious cycle fueled by mTOR dysregulation in hematopoietic stem cells. J Autoimmun. 2013;41:182–187.

- Fragoulis GE, Paterson C, Gilmour A, et al. Neutropaenia in early rheumatoid arthritis: frequency, predicting factors, natural history and outcome. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000739.

- Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010;102:83–87.

- Shih Y-H, Yang Y, Chang K-H, et al. Clinical features and outcome of lymphoma patients with pre-existing autoimmune diseases. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:93–101.

- Bjoro T, Holmen J, Krüger O, et al. Prevalence of thyroid disease, thyroid dysfunction and thyroid peroxidase antibodies in a large, unselected population. The Health Study of Nord-Trondelag (HUNT). Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:639–647.

- Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, et al. Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:692–701.

- Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–511.

- Rosenwald A, Staudt LM. Gene expression profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:S41–S47.

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1937–1947.

- Fu K, Weisenburger DD, Choi WWL, et al. addition of rituximab to standard chemotherapy improves the survival of both the germinal center B-cell–like and non–germinal center B-cell–like subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Jco. 2008;26:4587–4594.

- Löfström B, Backlin C, Sundström C, et al. A closer look at non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases in a national Swedish systemic lupus erythematosus cohort: a nested case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1627–1632.