Introduction

About 20% of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) progress or relapse after first-line therapy [Citation1,Citation2]. High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard of care for patients responding to second line chemotherapy [Citation3]. Therapeutic options are still limited in cases relapsing after ASCT and patients ineligible for ASCT because of age, comorbidities or lack of response to second-line treatment.

Brentuximab vedotin (BV) is an antibody-drug conjugate delivering the microtubule-disrupting cytostatic compound monomethyl auristatin E to CD30 expressing cells. In patients with relapse after ASCT BV resulted in complete response (CR) and overall response (OR) rates of 34% and 75%, respectively [Citation4]. With extended follow up, 89% and 41% of patients were alive at 1 and 5 years [Citation5]. In 2011, BV was approved for the treatment of cHL with relapse after ASCT or following at least two lines of chemotherapy in transplant-ineligible patients.

Following approval of BV, real-world experience in patients with post-ASCT relapse has supported the early data, and a number of patients may be candidates for a second, mostly allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) [Citation6–8]. No randomized comparison for patients with post-ASCT has been performed, but a real-world comparison of BV versus other chemotherapeutic regimens and registry data have indicated a benefit for BV [Citation9,Citation10].

Less data for BV is available in patients ineligible for a first SCT because of an inadequate response to salvage therapy. Early phase I and observational studies demonstrated that BV alone results in OR rates of 40–75% and may allow for a successive SCT in about 30–100% of cases [Citation8,Citation11–16].

In both categories of patients with relapsed or refractory (r/r) cHL the potential benefit of consolidation with SCT in patients responding to BV is emphasized [Citation16]. Little focus has been given to the use of radiotherapy after BV [Citation17,Citation18].

We report the experience with BV in r/r cHL in Norway for patients treated within the approved indications from 2011 to 2016. Consolidation of responses to BV was achieved by radiotherapy in isolated patients. For post-ASCT relapse, we compare survival for BV treated and national historical control patients prior to the introduction of BV.

Material and methods

Patients

During 2011–2016, BV was administered at the four university hospitals only, and patients were identified through hospital records. Only patients receiving BV, alone or in combination with bendamustine, according to the approved indication were considered, i.e., patients with cHL relapsed after ASCT or r/r to at least two lines of prior chemotherapy. Patients were considered candidates for SCT in case of a response to BV, age below 65–70 years and in the absence of relevant comorbidity, others were ineligible for SCT. Patients with a relapse after allogeneic SCT were considered ineligible for further SCT. Information was retrieved from medical records. With the Deauville scoring system in use from 2010 in Norway, the response to BV could be recorded retrospectively according to the Lugano criteria, with Deauville score ≤3 defining CR [Citation19]. Updates for surviving patients were collected last in March 2019. Patients treated with BV for a post-ASCT relapse were compared to 49 patients that underwent ASCT for r/r cHL between 1987 and 2008 and relapsed before 2011, all part of a recent national survey [Citation20].

Treatment

BV was given as a 30-minute infusion at 1.8 mg/kg, not higher than 180 mg [Citation4], repeated every three weeks. Transplant-eligible patients responding to BV were planned to undergo consolidation with a SCT, but radiotherapy to all areas involved at relapse was used in isolated cases. Transplant ineligible patients continued, in the absence of severe toxicities or progression, for further 4–6 cycles after best response. With bendamustine, BV was given on day 1 and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on day 1 and 2 of a 3 week cycle until best response followed by consolidation or for a maximum of 6 cycles. In general, dose reduction to 1.2 mg/kg was performed in neuropathy grade 2 and BV omitted in grade 3, otherwise recommendations in the label were followed.

Statistics

Mann–Whitney U and Chi-square tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, and PFS and OS calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier and compared using the log-rank test. PFS was recorded from first BV treatment until progression or death of any cause. OS was recorded from the first cycle of BV or other chemotherapy until the death of any cause. Three historical patients alive with active disease in 2011 were able to receive BV and therefore censored at the time of BV treatment. The significance level was 0.05 and all tests two-sided.

Ethics

The study was approved by the South East Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2018/84).

Results

Thirty-four patients (median age 38 years) with r/r cHL received BV at the four university hospitals in Norway (Supplemental Table 1). In all cases, the latest available histology report stated CD30 expression. Twenty-seven patients were transplant-eligible in case of a response to BV-based salvage treatment, with 17 relapsing after ASCT and 10 ASCT naïve patients refractory to the last of at least two lines of chemotherapy. Seven patients had r/r disease after at least two lines of chemotherapy but were ineligible for transplant due to age, comorbidities or prior ASCT and allogeneic SCT.

Twenty-four patients received BV alone, 10 patients received BV with bendamustine, for a median number of cycles of 5 (range 1–9), with CR achieved in 58% and 60% of patients in the two groups, respectively. Responses to BV and further treatment according to subgroup are given in . For patients relapsing after ASCT, 11 responded with a CR and underwent consolidation with an allogeneic SCT (7 patients) or radiotherapy to all involved sites at relapse (3 patients). One patient with a localized relapse within a mediastinal radiation field had the residual PET-negative tumor removed surgically. Six out of 10 transplant-naïve patients with refractory disease responded with a CR and went on to transplant, 5 with ASCT and 1 with allogeneic SCT because of poor mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. One patient with stable disease after BV received mediastinal radiotherapy to the site of PET-positive tumor and subsequently underwent an allogeneic SCT. Of the 7 SCT ineligible patients four responded, but subsequently progressed (median duration of response 6 months, range 6–34 months), 3 of them while on BV treatment. Other patients in either group with less than a CR received no further treatment or palliation chemotherapy.

Table 1. Treatment details and response.

Patients who received BV for post-ASCT relapse had a median PFS of 2.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] not assessable) years whereas the median OS was not reached (Supplemental Figure 1). PFS and OS rates at three years were 46% (95% CI = 22–70% and 70% (47–92%), respectively. For patients treated with the aim of a first transplant, median PFS was 0.9 years (95% CI not assessable), and median OS was not reached. Rates of PFS and OS at three years in this group were 50% (19–80%) and 70% (46–95%). The small group of transplant-ineligible patients had a poor outcome with a median PFS of 0.5 (0.1–0.9) years and OS of 1.9 (0.1–3.7) years.

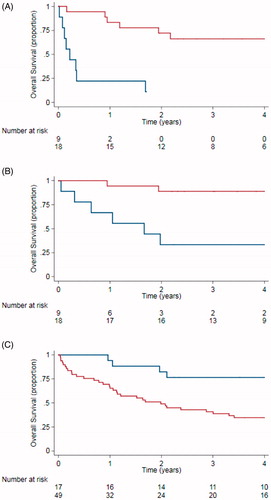

Outcomes for all transplant eligible patients, according to response and use of consolidation, are depicted in . Those responding to a CR (including one patient with a CR after radiotherapy to PET positive disease after BV) and consolidated with a first transplant (mainly ASCT), a second transplant (always an allogeneic SCT), with radiotherapy or surgery had five year PFS and OS rates of 70% (48–92%) and 74% (44–100%), respectively. The three patients with post-ASCT relapse that received consolidation radiotherapy are relapse-free at 5.3, 5.9 and 7.7 years. After allogeneic SCT, three patients are dead of toxicities, three patients have relapsed (but two successfully retreated with BV) and three are alive without a relapse 2.3, 3.5 and 6.4 years after treatment. Patients with less than a CR and therefore no consolidation had a median PFS and OS of 0.2 years (0–0.5) and 1.7 (0.4–2.9) years, respectively, whereas the median PFS and OS had not been reached in the others.

Figure 1. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) using consolidation after brentuximab vedotin. Red line: patients receiving consolidation treatment. Blue line: No consolidation. Overall survival for patients relapsing after autologous stem cell transplant by cohort (C). Blue line: Patient with relapse after autologous stem cell transplant treated with brentuximab vedotin 2011–1016. Red line: Patients with relapse after autologous stem cell transplant not treated with brentuximab vedotin 1987–2011.

Survival of patients with post-ASCT relapse treated with BV since 2011 and patients relapsing prior to 2011 are shown in . The median time from ASCT to relapse was similar, 0.7 years (0.5-0.9) in BV treated patients and 0.6 years (0.4-0.7) in controls (p = .65) as were sex distribution, number of previous lines of chemotherapy, prior use of radiotherapy, age at ASCT and use of radiotherapy (data not shown). More patients underwent an allogeneic SCT after BV treatment, 7 out of 17 patients (35%), than in the historical control group, 7 out of 47 (15%; p = .01). Median OS in the BV group had not been reached, compared to 2.0 (1.2–2.8) years for controls (p = .011). The 5-year survival rate in the BV group was 71% (95% CI: 49–92%) compared to 25% (13–38%) for the control cohort.

Discussion

We report the experience with BV in Norwegian r/r cHL patients during the first 5 years of routine use, supplementing other real-world data in this rare disease category. In patients with a post-ASCT relapse or transplant-naïve patients with refractory disease, BV alone or combined with bendamustine is able to induce remissions and allows for consolidation with a first or second SCT or radiotherapy in a substantial number of patients. Long term outcome in patients with a complete response to BV and subsequent consolidation is encouraging.

Real-world data from different sources support the use of BV in patients with a post-ASCT relapse [Citation6–9,Citation13]. However responses appear short-lived, and only patients with a CR according to the criteria of the pivotal trial have a realistic chance of long-term survival [Citation5]. Consolidation with a second, mostly allogeneic, SCT is advocated by some authors [Citation13,Citation21,Citation22]. Our data support the use of consolidation and an allogeneic SCT following BV has been used more often since the introduction of BV. Interestingly, we have used radiotherapy encompassing sites of relapse in selected patients avoiding the toxicity associated with allogeneic SCT. The use of radiotherapy following BV was explored by others, but we report here long term outcome [Citation17,Citation18].

We assessed the benefit of BV in the post-ASCT relapse situation by comparing patients treated with BV and a population-based historical cohort [Citation20]. With no systematic differences in baseline characteristics, survival improved significantly. This may not only be due to the introduction of BV, but also other improvements in therapy over the last years, most notably the use of allogeneic SCT in a higher proportion of patients and the introduction of programmed-death receptor (PD)-1 inhibitors. Only 3 patients in this cohort had received a PD-1 inhibitor after BV with two responding patients. Censoring at time of initiation of PD-1 inhibitors did not alter the conclusion. Since most patients responding to BV salvage treatment after ASCT were offered an allogeneic SCT, it is difficult in our small study to tease out the relative contribution of BV and the increased use of allogeneic SCT. However, other studies have suggested that the higher responses rates and more favorable toxicity profile of BV compared to historical salvage regimens may render more patients suitable for an allogeneic transplant. A recent national study from Greece with a similar design also found a higher rate of allogeneic SCT and improved survival in patients treated with BV for a post-ASCT relapse, even when censoring at time of the second SCT [Citation10].

Observational data also support the use of BV in patients with r/r disease that do not respond adequately to salvage chemotherapy, but would otherwise be suitable for transplant [Citation8,Citation11–16]. Few investigators have reported on the durability of responses thus consolidated. In this regard, our observational study adds support to the approach of an ASCT following BV. 5 out of the 10 patients remain in remission 2->5 years after SCT. After introduction in the beginning of 2017, two patients in our cohort received BV consolidation after ASCT, which may have contributed to the results [Citation23,Citation24].

The benefit of BV in patients unable to undergo any form of consolidation SCT is not well studied. Our results in a limited number of patients ineligible for a SCT due to age or comorbidity suggest that most patients progress on therapy or shortly after the end of treatment, even in the case of a CR. Long term outcome of treatment with BV only in r/r cHL patients could provide stronger evidence for the palliative use of this expensive drug in transplant-ineligible patients [Citation25]. We encourage the systematic evaluation of consolidative radiotherapy in transplant-ineligible patients.

The strength of our study resides in the coverage of all r/r cHL BV treated patients in Norway five years following approval with complete and long follow-up. Due to referral practices and high costs of BV, it is unlikely that patients have received BV outside of the university centers. However, due to the small population of our country, the number of patients within each approved indication is limited. Since patients were allowed to have BV combined with bendamustine and responding transplant eligible patients were offered and underwent a SCT or other consolidation, the relative contribution of BV alone to the encouraging results is difficult to address in detail. This also holds true for the historical comparison to patients with a post ASCT relapse before the introduction of BV in 2011. Furthermore, during the study period, patients with r/r cHL may not have been offered treatment with BV, especially elderly and frail, transplant-ineligible patients, representing a potential bias in our results.

In conclusion, and despite the limitation in retrospective analyses of small numbers of patients, our Norwegian data add to the existing evidence that BV is associated with meaningful response rates in patients with r/r HL. Together with an increased use consolidation treatment, long term outcomes seem to improve.

Supplemental Material

Download (29.3 KB)Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligation as researchers, we are reporting that: AF has received honoraria from Takeda, BMS, MSD, Janssen and Roche, and received research support from and taken part in advisory boards for Takeda. HH has received honoraria from Novartis and has taken part in advisory boards for Takeda, Roche, Celgene, Novartis and Nordic Nanovector.

References

- Carella AM, Corradini P, Mussetti A, et al. Treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of brentuximab vedotin and immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1301–1315.

- Shanbhag S, Ambinder RF. Hodgkin lymphoma: a review and update on recent progress. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:116–132.

- Rancea M, von Tresckow B, Monsef I, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat. 2014;92:1–10.

- Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2183–2189.

- Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128:1562–1566.

- Zinzani PL, Sasse S, Radford J, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: An updated review of published data from the named patient program. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;104:65–70.

- Pellegrini C, Broccoli A, Pulsoni A, et al. Italian real life experience with brentuximab vedotin: results of a large observational study on 234 relapsed/refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:91703–91710.

- Angelopoulou MK, Vassilakopoulos TP, Batsis I, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. The Hellenic experience. Hematol Oncol. 2018;36:174–181.

- Zagadailov EA, Corman S, Chirikov V, et al. Real-world effectiveness of brentuximab vedotin versus physicians' choice chemotherapy in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma following autologous stem cell transplantation in the United Kingdom and Germany. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2018;59:1413–1419.

- Tsirigotis P, Vassilakopoulos T, Batsis I, et al. Positive impact of brentuximab vedotin on overall survival of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma who relapse or progress after autologous stem cell transplantation: a nationwide analysis. Hematol Oncol. 2018;36:645–650.

- Forero-Torres A, Fanale M, Advani R, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in transplant-naive patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: analysis of two phase I studies. Oncologist. 2012;17:1073–1080.

- Walewski J, Hellmann A, Siritanaratkul N, et al. Prospective study of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma patients who are not suitable for stem cell transplant or multi-agent chemotherapy. Br J Haematol.. 2018;183:400–410.

- Pavone V, Mele A, Carlino D, et al. Brentuximab vedotin as salvage treatment in Hodgkin lymphoma naive transplant patients or failing ASCT: the real life experience of Rete Ematologica Pugliese (REP). Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1817–1824.

- Zinzani PL, Pellegrini C, Cantonetti M, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in transplant-naive relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: experience in 30 patients. Oncologist. 2015;20:1413–1416.

- Onishi M, Graf SA, Holmberg L, et al. Brentuximab vedotin administered to platinum-refractory, transplant-naive Hodgkin lymphoma patients can increase the proportion achieving FDG PET negative status. Hematol Oncol. 2015;33:187–191.

- Eyre TA, Phillips EH, Linton KM, et al. Results of a multicentre UK-wide retrospective study evaluating the efficacy of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed, refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma in the transplant naive setting. Br J Haematol. 2017;179:471–479.

- Dozzo M, Zaja F, Volpetti S, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in combination with extended field radiotherapy as salvage treatment for primary refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:E73

- Monjanel H, Deville L, Ram-Wolff C, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in heavily treated Hodgkin and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, a single centre study on 45 patients. Br J Haematol.. 2014;166:306–308.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. JCO. 2014;32:3059–3068.

- Smeland KB, Kiserud CE, Lauritzsen GF, et al. Conditional survival and excess mortality after high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation for adult refractory or relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma in Norway. Haematologica. 2015;100:e240–3.

- Chen R, Palmer JM, Thomas SH, et al. Brentuximab vedotin enables successful reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2012;119:6379–6381.

- Mediwake H, Morris K, Curley C, et al. Use of brentuximab vedotin as salvage therapy pre-allogeneic stem cell transplantation in relapsed/refractory CD30 positive lympho-proliferative disorders: a single centre experience. Intern Med J. 2017;47:574–578.

- Moskowitz CH, Nademanee A, Masszi T, et al. Brentuximab vedotin as consolidation therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma at risk of relapse or progression (AETHERA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1853–1862.

- Moskowitz CH, Walewski J, Nademanee A, et al. Five-year PFS from the AETHERA trial of brentuximab vedotin for Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of progression or relapse. Blood. 2018;132:2639–2642.

- Brockelmann PJ, Zagadailov EA, Corman SL, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma who are Ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant: a Germany and United Kingdom retrospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99:553–558.