Abstract

Purpose: To date, no clinical study has reported on the optimal treatment duration of PD-1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Worldwide, concern has been expressed that due to the high cost of anti-PD-1 therapy, it is not available for all patients. After approval of anti-PD-1 therapy as a first-line treatment, the Helsinki University Hospital institutional board for new drugs decided to treat the first patient cohort within a limited treatment duration program in order to offer this treatment to as many patients as possible.

Patients and methods: The first 40 patients with metastatic melanoma initiating treatment at Helsinki University Hospital were to be treated within a six months maximum limited duration program. Patient follow-up was systematic according to a prospectively planned treatment protocol to enable evaluation of treatment efficacy and the safety of this treatment approach.

Results: Thirty-eight patients were treated within the program. Seventeen out of these 38 patients completed the six-month regimen. Five discontinued treatment early due to toxicity, and 16 discontinued due to progressive disease. The response rate (RR) for all patients was 39%, but only 33% of these responses are ongoing. Median progression-free survival (PFS) for patients who completed the six-month therapy was 12 months (range, two to 44 months), and median overall survival (OS) has not yet been reached.

Conclusions: Although RR is comparable to published data, the response duration is shorter. Based on our results, limiting treatment to only six months may increase the risk of shortening response duration.

Introduction

Checkpoint inhibitors and therapies targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway have significantly improved the treatment outcomes of metastatic melanoma and are now in routine use. Ipilimumab [Citation1] was the first treatment to demonstrate improved survival in metastatic melanoma patients, followed by vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor. Both treatments are superior to dacarbazine [Citation2]. Treatment outcome has continued to improve through the introduction of programmed death -1 antibodies (anti-PD-1) nivolumab and pembrolizumab and the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors, combination immunotherapy with ipilimumab and nivolumab has further improved treatment outcome [Citation3–7].

In the early-phase ipilimumab trials, treatment continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity [Citation8,Citation9]. Likewise, in the early anti-PD-1 trials, treatment duration depended on disease progression or unacceptable toxicity [Citation3,Citation4]. However, the trial leading to FDA approval of ipilimumab was designed differently, with limited treatment duration, that is, four infusions of Q3W [Citation1]. In regard to the anti-PD-1 agents, Schachter et al. [Citation10] were the first to report results from a trial with a two-year treatment duration in the absence of disease progression or treatment-limiting toxicity. As of yet, the optimal duration of anti-PD-1 therapy for metastatic melanoma remains unestablished.

Although immune checkpoint inhibitors enhance survival in patients with metastatic melanoma, they are also associated with toxicity and high costs. Unnecessarily long treatment duration may result in increased toxicity, have a negative effect on the cost-effectiveness of therapy, and put a strain hospital capacity to treat an increasing number of cancer patients. The high economic burden of immune checkpoint inhibitors has led to deep-level differences in their availability and out-of-pocket costs in Europe [Citation11]. Limiting treatment duration would result in significant cost savings, thus providing the opportunity to treat more patients.

Finland has a publicly funded healthcare system, which ensures treatment for all. Expanding healthcare budgets and increasingly expensive new treatments are placing the welfare system at risk. The institutional medical board at the Helsinki University Hospital evaluates all new expensive treatments before accepting them into practice. Anti-PD-1 agents were approved as a first-line treatment for metastatic melanoma in 2015. At that time, no knowledge existed on optimal anti-PD-1 therapy duration. Since there was no planned or ongoing clinical trial evaluating limited treatment duration, the institutional board for new drugs required a pilot study to be conducted within a treatment program with limited treatment duration. Forty patients were to be treated with anti-PD-1 therapy limited to a maximum of six months, with the option of retreatment at progression. The pilot study design was based on knowledge that limited-duration ipilimumab treatment had been proven feasible.

In this article, we report the clinical outcome of this prospective real-world treatment program, with 38 metastatic melanoma patients receiving anti-PD-1 treatment limited to a maximum of six months.

Material and methods

Patients and treatment program

Permission from an independent institutional review board was issued for this treatment program. Patients with cutaneous, acral, or mucosal metastatic melanoma in need of first-line treatment were included and treated with either pembrolizumab or nivolumab both being available at the hospital’s pharmacy. Treatment was limited to a maximum duration of six months with the possibility of retreatment at disease progression.

Criteria for starting anti-PD-1 therapy were the same as in most clinical anti-PD-1 trials, that is, unresectable stage III or IV metastatic melanoma, at least one measurable lesion, ECOG performance status 0 or 1, no active autoimmune disease requiring corticosteroid treatment exceeding Prednisone 10 mg or equivalent, and no active brain metastases. Treatment decisions were made by an interdisciplinary meeting before treatment initiation.

Patient follow-up was systematic according to a prospectively planned treatment protocol. A comprehensive laboratory workup, a whole-body CT scan, and a brain MRI or CT were performed at baseline prior to treatment commencement, and thereafter every 12 weeks unless clinical signs of progression or adverse events (AEs) occurred. Before each infusion, patients underwent clinical assessment, with concomitant medication and AEs registered, and laboratory parameters were monitored.

A radiologist interpreted responses were determined using the RECIST criteria [Citation12]. As the added benefit of immunological response criteria in clinical setting is uncertain, we decided not to use any in our study [Citation13]. AEs were graded using the common terminology for adverse events (CTCEA) version 4.0 [Citation14].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses utilized SPSS Statistics® version 22. Descriptive statistics served to determine baseline characteristics of the pilot study population. Data comprised patient age, gender, primary melanoma, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage at treatment initiation (version 7) [Citation15], brain metastases, previous treatments, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; categorized as ≤ ULN, > ULN) at baseline, anti-PD-1 therapy (pembrolizumab/nivolumab), AEs, response to treatment, retreatment, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Follow-up was the time from initiation of anti-PD-1 therapy to the last follow-up or death. Time on treatment was time between the date of treatment initiation and the date of last drug administration. PFS and OS were estimated using Kaplan Meier method. PFS after anti-PD-1 therapy was calculated from treatment initiation to the date of progressive disease (PD), death, or last follow-up, whichever occurred first. OS was calculated from treatment initiation to date of death or latest follow-up. Date of data cutoff was 30 October 2019.

Results

Thirty-eight patients with metastatic melanoma were included in this pilot study between November 2015 and March 2017 at the Helsinki University Hospital. Median follow-up time was 25 months (range, one to 47 months). Out of 38 patients, 15 were treated with nivolumab and 23 with pembrolizumab. The treatment selection was random and made by the treating physician. Nearly, half of the patients had M1c disease and an elevated LDH. Further patient characteristics are shown in . Median treatment duration was three months (range, 0 to six months).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

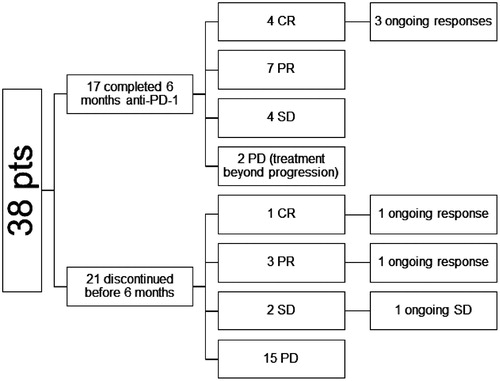

Five patients had a complete response (CR) (13%) and 10 patients (26%) had a partial response (PR) as best response, corresponding to an overall response rate (RR) of 39%. Six patients (16%) had stable disease (SD) and 17 patients (45%) had PD ().

Figure 1. Responses. CR: complete response; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

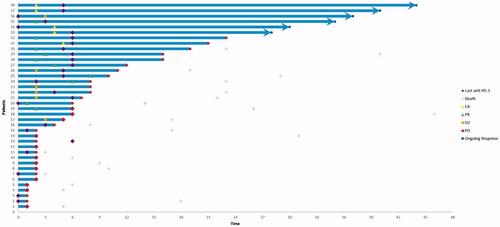

Five (33%) out of 15 responding patients had ongoing responses at the data cutoff point on 30 October 2019. Four patients out of five with confirmed CR as best overall response were still in remission after a median follow-up of 31 months from the first detection of CR. Two of the patients remaining in remission had a CR already at the first response evaluation, and CR was registered at the second response evaluation for two patients ().

Figure 2. Time and duration of response. Swimmers plot showing time to best response and duration of response for patients who received anti-PD-1 therapy (pembrolizumab or nivolumab).

Ten patients achieved a PR. Three of these patients had to stop treatment due to toxicity before six months (range, 0 to three months). Seven PR patients discontinued therapy at six months. Five of these patients had metastases that were still shrinking on the two consecutive response evaluations conducted during treatment. All seven PR patients experienced a recurrence during follow-up.

After the first response evaluation, 15 patients discontinued treatment due to progression, whereas two patients continued treatment beyond progression. Progressive disease (PD; 42%) and AEs (13%) were the reason for early treatment discontinuation.

17 patients (45%) completed the six-month anti-PD-1 treatment. Out of these, 11 patients responded to treatment (4 CR, 7 PR). However, only three (27%) have ongoing responses.

Six patients were retreated with anti-PD-1 at progression. The RR for retreatment was 50%. All these patients had discontinued retreatment at the data cutoff.

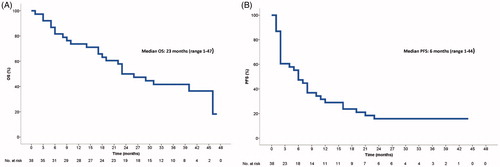

Median PFS for all patients was six months (range, one to 44 months), whereas 14 out of 17 patients finishing the six-month anti-PD-1 treatment progressed during follow-up with a median PFS of 11 months (range, two to 23 months). Median OS () has not yet been reached (range, one to 47 months).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curves of (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival in 38 patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy.

AEs are listed in . The safety profile observed in patients treated with limited treatment duration was similar to that reported previously by others [Citation3,Citation9,Citation10]. Five (13.2%) patients required hospitalization due to a serious AE, but most treatment-related AEs in our current study were grades 1– 2 and no treatment-related deaths occurred.

Table 2. Treatment related adverse events.

Discussion

Both pembrolizumab and nivolumab have demonstrated robust antitumor activity in metastatic melanoma with response rates ranging from 30% to 40% and CR rates between 5% and 16% [Citation3,Citation16–19]. Data on patients discontinuing therapy early for reasons other than disease progression or toxicity are scarce. In a situation where treatment costs are expanding, the pressure to find an optimal duration of effective treatment increases.

Exposure to treatment was considerably shorter during this pilot study than in published trials designed to continue either until disease progression or dose-limiting toxicity [Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation19], or for a maximum duration of two years [Citation10] in the absence of progression or treatment-limiting toxicity. Overall response rate (ORR) was 39% (5 CR, 10 PR) despite limited treatment duration, confirming that responses are achievable in a real-life setting with similar probability as reported in clinical trials. Robert et al. [Citation18] reported that the majority of patients achieving a CR had a PR at first evaluation several months before the occurrence of CR, with a median duration of 11 months between PR and CR. This indicates that even if a PR is achieved early, many patients require longer exposure to treatment to improve their best response. The responding patients in our pilot study stopped treatment at six months irrespective of the response pattern. All but one patients with CR have continued in response. Those patients discontinuing treatment while their metastases were still shrinking would potentially have benefited from longer therapy and their response may potentially have converted into a CR with longer treatment duration. Compared to the KEYNOTE-006 data, our data showed a trend to fewer SD patients (23.5% vs. 16.8%, respectively). Hence, patients with SD may also have profited from prolonged treatment duration. It also appears likely that some responses could have improved, and some delayed responses were missed due to premature treatment termination.

In our study, four responding patients (one CR, three PR) had to stop treatment prematurely due to toxicity. The CR patient’s response is still ongoing, whereas two out of the three PR patients have progressed.

Ladwa et al. [Citation20] reported real-life results when discontinuing anti-PD-1 therapy intentionally after achieving a CR. Disease progression rate was low after treatment discontinuation. The median duration of therapy was 12.5 months for patients who entered therapy through an early access program, but only nine months for those who received reimbursed therapy. This is not surprising, as clinicians and patients prefer treatment breaks after CR in clinical practice, as long as data on optimal treatment duration are lacking [Citation20].

In contrast to published data, 67% (10/15) of our responding patients including one with CR have progressed after a median follow-up of 30.5 months. A recent update of the KEYNOTE-006 reported that 74% (76/103) of the patients who completed two-year pembrolizumab treatment were progression-free at a median follow-up of 57.7 months [Citation21]. Similarly, in the KEYNOTE-001 trial, 73% of all responses and 82% of responses of treatment-naive patients were ongoing after a median follow-up of 55 months [Citation22]. However, it is important to note that after a median follow-up of 55 months, 35 patients in the KEYNOTE-001 trial were still on pembrolizumab treatment [Citation18,Citation22]. Compared to the results of both these trials, our patients faired considerably worse.

Accumulating evidence suggests that if patients achieve a CR, anti-PD-1 treatment cessation is possible, with a low probability of early relapse. However, no data exist on the optimal moment to discontinue treatment after a confirmed CR, to ensure a durable response. Jansen et al. [Citation23] reported recently that in patients from a real-world cohort who achieved a CR but were treated < 6 months the risk of progression was significantly higher than in patients treated ≥6 months. In our treatment program with treatment duration limited to only six months, four patients out of five (80%) with CR remain in response during follow-up.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on metastatic melanoma patients receiving six-month limited-duration anti-PD-1 therapy. Our pilot study has several limitations, including a small patient number. Our patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria most commonly used in clinical phase-III trials. Compared to published data, our treatment program consisted of a slightly higher number of patients with elevated LDH, whereas we had less patients with M1c disease [Citation7,Citation10,Citation24]. Comparison of results between various trials should always be performed with caution, and although the sample size is small, our treatment strategy with predefined limited treatment duration shows inferiority in maintaining durable responses. So far, data on the effectiveness of retreatment at progression are based on small patient series and have not been reassuring [Citation21,Citation23,Citation25]. Although certain patients profit from retreatment, it may not compensate for premature treatment termination. Loss of responses due to premature termination of anti-PD-1 therapy leads to further need for treatment and accumulated treatment costs.

New trials, like the Canadian STOP-GAP study (NCT02821013) and the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) portfolio DANTE trial (ISRCTN15837212) have been designed to evaluate optimum treatment duration. Before these trials report results, close monitoring and reporting of accumulating real-world data provides valuable information on this question.

Conclusion

Based on our results, we have revised our treatment strategy and now will continue treatment until response stabilization, until further evidence evolves concerning safe early treatment termination. The results of our pilot study should serve as caution for those considering treatment termination for metastatic melanoma patients on anti-PD-1 treatment outside clinical trials.

Disclosure statement

SM, LK and MH have had a paid consulting or advisory role with MSD and/or BMS. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723.

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516.

- Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–330.

- Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):908–918.

- Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dreno B, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1248–1260.

- Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444–451.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34.

- Weber JS, O’Day S, Urba W, et al. Phase I/II study of ipilimumab for patients with metastatic melanoma. JCO. 2008;26(36):5950–5956.

- O’Day SJ, Maio M, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a multicenter single-arm phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(8):1712–1717.

- Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet. 2017;390(10105):1853–1862.

- Cherny N, Sullivan R, Torode J, et al. ESMO European Consortium Study on the availability, out-of-pocket costs and accessibility of antineoplastic medicines in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1423–1443.

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States. National Cancer Institute of Canada. 2000;92(3):205–216.

- Borcoman E, Nandikolla A, Long G, et al. Patterns of Response and Progression to Immunotherapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;2018/09(38):169–178.

- National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events: (CTCAE). v403 ed. Bethesda, MD.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2010.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. JCO. 2009;27(36):6199–6206.

- Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1600–1609.

- Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521–2532.

- Robert C, Ribas A, Hamid O, et al. Durable complete response after discontinuation of pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. JCO. 2018;36(17):1668–1674.

- Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375–384.

- Ladwa R, Atkinson V. The cessation of anti-PD-1 antibodies of complete responders in metastatic melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(2):168–170.

- Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019; 20(9):1239–1251.

- Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. 5-year survival outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(4):582–588.

- Jansen YJL, Rozeman EA, Mason R, et al. Discontinuation of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1154–1161.

- Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2006–2017.

- Nomura M, Otsuka A, Kondo T, et al. Efficacy and safety of retreatment with nivolumab in metastatic melanoma patients previously treated with nivolumab. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2017;80(5):999–1004.