Abstract

Background: The population of breast cancer survivors is increasing as a positive consequence of early detection and enhanced treatment. The disease and treatment associated side-effects or late-effects often impact on quality of life and daily life functions during survivorship. This calls for optimization of follow-up care. We aimed to evaluate the patients’ satisfaction with the care provided, when using electronic patient reported outcomes (ePROs) to individualize follow-up care in women with early breast cancer receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy.

Material and methods: Postmenopausal women treated for hormone receptor positive early breast cancer were included in a pilot randomized controlled trial and randomized to receive standard follow-up care with prescheduled consultations every six months or individualized follow-up care with the active use of ePROs to screen for the need of consultations. ePROs were distributed every third month over a two-year period. Primary outcomes were satisfaction with the assigned follow-up care and unmet needs. Secondary outcomes were use of consultations, adherence to treatment and quality of life.

Results: Of the 207 consecutive patients who were potentially eligible for the study, 134 women were enrolled (65%). In total 64 women in standard care and 60 women in individualized care were analyzed. No statistically significant differences were reported in relation to satisfaction, unmet needs, adherence to treatment or quality of life. Women in standard care attended twice as many consultations during the two year follow-up period as women in individualized care; 4.3 (95% CI 3.9–4.7) versus 2.1 (95% CI: 1.6–2.6), p < .001.

Conclusion: A significant reduction in consultations was observed for the group attending individualized care without compromising the patients’ satisfaction, quality of life or adherence to treatment. For the majority of postmenopausal women treated for early breast cancer, implementation of ePROs to individualize follow-up care was feasible.

Introduction

Women treated for early breast cancer represent the largest group among cancer survivors [Citation1]. In Denmark the five-year relative survival rate for all breast cancer stages is 87% [Citation2]. Due to early detection and enhanced medical treatment options, survival rates continue to improve, which consequently increases the population of survivors [Citation3].

The purpose of follow-up care is early detection of recurrence or new primary breast cancers, identification and treatment of therapy-related side effects or sequelae, and provision of psychological support to the patients [Citation4,Citation5]. It is well recognized that many survivors develop short- and long term physical and psychosocial side effects as a result of their diagnosis and treatment. Several studies have provided evidence that women treated for early breast cancer report substantially more disease- and treatment related side effects and long-term effects, than are recorded by clinical oncologists [Citation6–9]. This discrepancy between patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of well-being, often results in patients expressing unmet needs during follow-up care [Citation10–14].

The Danish health care system is tax-funded, and provides free-of-charge access for Danish citizens to all public hospitals. According to newly published guidelines from the Danish National Board of Health, all patients who are prescribed a specific oncological treatment, like adjuvant endocrine therapy, should be taken care of by the nearest hospital-based department of oncology. Further, the guidelines highlight that except for regular mammography there is no evidence that routine examinations improve overall survival after breast cancer [Citation15–17]. Therefore the guidelines recommends individualized follow-up care, but gives no guidance on how this should be achieved [Citation15].

From a political, organizational, and patient advocacy perspective there is a growing interest in bringing ‘the patient’s perspective’ into decision making in cancer care [Citation18–20]. The provision of patient-centered care that accommodates the needs of the individual, requires a health care environment that fosters engagement between the patient and her health care team [Citation21]. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) measure the patient’s view of her health status and may be useful for the engagement and involvement of the patient [Citation22–26]. PROs are particularly useful in cancer care, as the patients’ subjective experience and functioning is often affected by sequelae of the cancer, late effects to treatment and associated psychosocial factors [Citation27–30].

We hypothesized that it would be feasible to individualize follow-up care by the use of electronically collected PROs (ePROs) and that patients would be equally satisfied with such a solution compared to the current standardized follow-up program. We conducted a pilot randomized trial with the aim to evaluate patients’ satisfaction with individualized follow-up care for postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer compared to standard follow-up care and thereby justify implementation of the intervention in a larger scale, multi-center, randomized trial. Furthermore, this pilot trial could assist decision making of what should be the main outcome in a future trial evaluating efficacy.

Material and methods

Study design

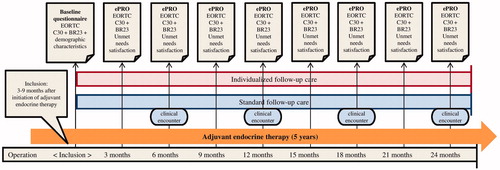

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to evaluate patient’s satisfaction with an individualized follow-up care (IC) compared to standard follow-up care (SC). Electronic patient reported outcomes (ePROs) were collected in both groups, but only used actively to perform individualized care in the intervention group. In SC ePROs were solely collected as an outcome measure for the study. shows a timeline of the distribution of questionnaires in SC and IC.

Study population

Participants were recruited from April 2016 throughout June 2017 from the Department of Oncology at Lillebaelt Hospital – University Hospital of Southern Denmark. Patients were randomized 1:1 by a computer generated sequence between SC and IC. The eligibility criteria were Danish-speaking women, age ≥ 50, who were postmenopausal at the time of diagnosis (menostasis > 12 month or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), had histologically verified hormone-receptor positive (nuclei staining ≥1%) early stage breast cancer (stadium I-III), classified as in complete disease remission after primary surgery, and scheduled for at least five years of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Patients were invited to participate in the study within nine months of initiation of endocrine therapy. As PROs were collected electronically, patients needed sufficient computer capabilities to receive and send emails, and complete electronic questionnaires. A screening log was established to register reasons for exclusion.

Standard follow-up care (SC)

At the time of this study, SC consisted of pre-scheduled consultations at 6 monthly intervals for a period of five years. A clinician performed a clinical examination, and a nurse provided patients with their endocrine therapy and a standard infusion of zoledronic acid [Citation31]. Between visits patients could call the department, and were often encouraged to visit their general practitioner, or to seek advice or support at the counseling centers hosted by the Danish Cancer Society [Citation32]. Patients could also be referred to several oncological rehabilitation specialists, including psychologists, social workers, and physiotherapists. If deemed necessary, clinicians could refer patients to other hospital departments e.g., for problems related to comorbidity or breast reconstruction [Citation4,Citation15]. Mammography and ultrasound were offered 18–24 months after surgery, followed by a screening mammography every second year. Patients who were randomized to SC completed an electronic questionnaire every third month. At the time of enrollment they were informed that the questionnaires would not be examined before the end of study, as they were to be used to assess satisfaction, unmet needs and health related quality of life during follow-up care.

Individualized follow-up care (IC)

The intervention was a patient-initiated follow-up program customized to the needs of the individual. ePROs were collected every third month and used actively as (1) a screening tool to assess the patient’s problems and her individual requirements; (2) a dialogue tool to map the patient’s symptoms and concerns in order to focus the discussion on what mattered most to the individual patient.

No mandatory consultations were planned for the intervention group apart from the administration of medications. If the patient needed an additional consultation or a phone call with a specialized nurse, she could either report this via the electronic questionnaire, write an email, or call the department herself. A consultation was planned according to the urgency of the reported problems, and the results of the patient’s reported outcomes would be the focus of the dialogue. The principal investigator monitored incoming questionnaires and emails. If the patient reported severe side effects or emerging symptoms, but did not request a consultation, she was contacted by email to discuss how to handle these problems. The solution could be a consultation in clinic, a visit at her general practitioner or watchful waiting. Equally to standard care, patients were encouraged to use their general practitioner or counseling centers hosted by the Danish Cancer Society and were referred to other hospital departments or oncological rehabilitation specialists if indicated.

Patients in IC were invited to an evening group session held within approximately three months after recruitment to inform about the technicalities of the study and facilitate change management. During the session the purpose of the intervention and follow-up care was elaborated and the patient’s responsibilities were explained.

Measures and outcomes

The primary outcomes were satisfaction with the care provided and unmet needs as measured by four items from the Patient Experience Questionnaire (PEQ, Supplementary Figure 1) [Citation33]. At the end of the two-year follow-up period responses from the SC and IC groups were analyzed and compared sequentially at every time point. Satisfaction was measured by a single item with a 5-point scale and analyzed both as a mean and a proportional score. Three questions addressed unmet needs toward (1) procedures not offered, (2) concerns not provided for and (3) missing information. Each item was analyzed separately as the proportion of responders in each group, at each time point.

Secondary outcomes were use of consultations, adherence to treatment, self-reported symptoms, functioning, and health related quality of life. Data on the use of consultations and adherence to treatment was obtained by audit of electronic medical records. Adherence to treatment was categorized as (1) adherence to the primary prescribed drug during the whole study period, (2) change in endocrine therapy during the study period with continued adherence, or (3) discontinuation of adjuvant therapy. Quality of life, functioning and symptoms were assessed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30 version 3.0, Supplementary Figure 1) [Citation34,Citation35] and the EORTC breast cancer module (QLQ-BR23, Supplementary Figure 1) [Citation35,Citation36]. EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item questionnaire, which include five functional scales (physical, emotional, cognitive, social, and role), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea/vomiting), a global health related quality of life scale, and six single items on common symptoms. Twenty-seven out of the 30 items can be combined into a summary score, which gives an estimate of the patient’s health related quality of life based on all five functioning scales and all reported symptoms [Citation37]. EORTC QLQ-BR23 consists of 23 items and covers symptoms as well as side effects related to different treatment modalities, body image, sexuality and future perspective. The BR23 includes 4 functional scales and 4 symptom scales/items. The standard EORTC scoring algorithm was used to transform scores linearly to ranges of 0–100 [Citation38].

The questionnaires were distributed electronically and responses were encrypted and stored by the software system SurveyXact (Ramboll, Aarhus, Denmark). SurveyXact is the leading survey tool in Scandinavia and allows the user to design questionnaires and distribute them to respondents [Citation39,Citation40]. Along with informed consent, participants provided a private email address through which the women received a person-unique link to access the online questionnaires. The patients’ responses could not be accessed by the health professionals directly via the electronic medical record. An additional log-on procedure to SurveyXact was needed. Nor could the patients compare their own answers to previously submitted questionnaires.

If a patient did not respond to a questionnaire, she was reminded after 7 days, 14 days and 21 days approximately. Missing data at item level were limited since the electronic questionnaires required a response to each question, with the exception of the most personal issues e.g., sexual functioning.

Statistical analyses

The preplanned, primary outcomes of the trial were satisfaction and unmet needs. A sample size calculation for a full RCT was performed to test the number of patients needed for a non-inferiority study with a 10% margin in satisfaction, significance level at 95% and power of 90%. A sample of 380 women was needed for a full RCT. A sample of this size was not possible to achieve within the given timeframe and we therefore proceeded with a pilot randomized controlled trial to test the feasibility before the launch of a full size RCT. The sample size for the pilot randomized controlled trial was chosen based on the feasibility of completing the trial during the proposed timeframe with as many participants as possible. Approximately 200 postmenopausal women initiate adjuvant endocrine therapy annually at the Department of Oncology, Lillebaelt Hospital, so we anticipated reaching a sample of that size during an inclusion period of 15 months. Analysis was done per-protocol. Baseline characteristics were compared by chi-squared or Fishers’ exact test (in case of counts below five) for categorical characteristics. Normally distributed baseline characteristics were compared by t-tests. Adherence to treatment, satisfaction with follow-up care and the proportions reporting unmet needs were compared by chi-squared test. Mean score of satisfaction, mean use of consultations and EORTC sum-scores were compared between groups with Mann-Whitney U-test, to take into account non-normality of the scores. Further, a longitudinal comparison of differences in EORTC sum-scores between groups was done by linear mixed effects models, including the individual patient as random effect. p-values below .05 were considered statistically significant and all analyses were performed with STATA 15.1 (StataCorp 2017, Texas, USA).

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2008-58-035) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ID: NCT02935920). According to the Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects, no approval for this type of study was needed from the Danish Health Research Ethics Committee [Citation41].

Results

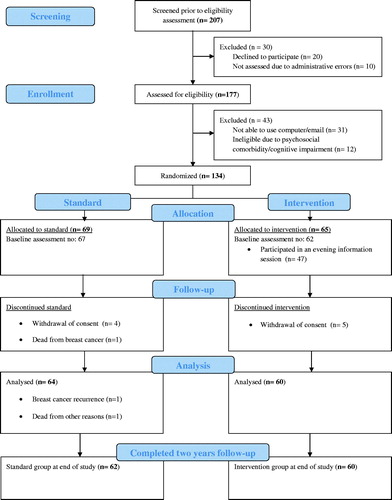

Of the 207 consecutive women screened to be eligible for this trial, 20 women (10%) declined to participate for personal reasons and 10 patients (5%) were not assessed due to administrative errors (). From the remaining 177 women who were assessed for eligibility, another 43 were excluded mainly due to the patient’s lack of technical skills or access to a computer; 31patients (72%) could not be enrolled for this reason. Twelve patients (28%) were not invited to participate due to psychosocial comorbidity or cognitive impairment. A total of 134 women agreed to participate with 69 randomized to SC and 65 to the intervention. Of the 65 women in the IC group, 47 women (72%) accepted an invitation to the evening information session. Participants in SC and IC did not differ by clinical or socio-demographic characteristics ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics among 129 women treated for early breast cancer and randomly assigned to standard follow-up care or individualized follow-up care.

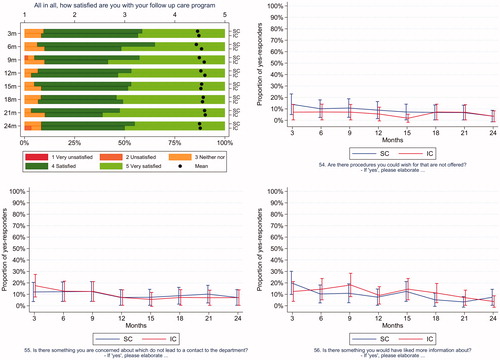

Satisfaction with follow-up care and unmet needs were compared across the two groups every third month (). In SC the response rates for completing ePROs were > 95% at every time point during the study period. In the IC group the response rates exceeded 98%. No statistically significant differences were observed at any point. Participants in both groups were highly satisfied with their follow-up care program throughout the study period.

Figure 3. Satisfaction and unmet needs. Satisfaction is presented as a mean score and a proportional score for patients in the standard follow-up care (SC) and in individualized follow-up care (IC). Unmet needs are presented as a comparison of the proportion of yes-responses to each item, at each time point.

On average, patients in SC attended 4.3 (CI 3.9–4.7) consultations each during the study period, compared to 2.1 (CI: 1.6–2.6) in patients attending IC (p < .001). The evaluation of adherence to treatment showed that 60 women (94%) in the SC group received endocrine treatment at the time of enrollment, compared to 59 women (98%) in the IC group (p = .37). At the end of the study 55 women (86%) in SC were still adherent to treatment compared to 51 women (85%) in the IC (p = 1.0). The proportion of women who changed their endocrine treatment during the study period was 28% in SC versus 23% in IC (p = .56).

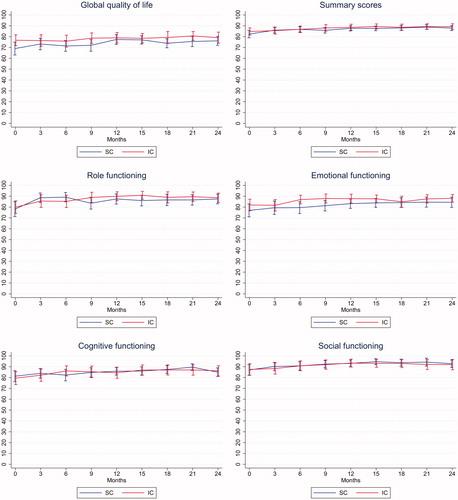

illustrates the longitudinal sum-scores of global quality of life, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, social functioning, and the summary score from the EORTC QLQ C30. Both groups have similar mean improvements in these measures and no other scale or symptoms obtained by the EORTC QLQ C30 or BR23 differed significantly between groups. Nor did the longitudinal linear mixed effects models show any significant difference between the two groups.

Figure 4. EORTC scales. Absolute mean scores obtained from both groups at each time point with 95% confidence intervals for global quality of life, summary score, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning. SC: Standard follow-up care; IC: Individualized follow-up care.

Discussion

This pilot randomized controlled trial evaluated satisfaction with individualized follow-up care for postmenopausal women treated for early breast cancer. We found that patients’ willingness to participate was high, but that a considerably part (21%) of this postmenopausal population could not be included due to psychosocial comorbidity, cognitive impairment, or lack of computer skills. These are known barriers in the routine implementation of electronically collected PROs [Citation42,Citation43]. Use of ePROs to individualize follow-up care is therefore unlikely to be feasible for all patients.

We anticipated that women would be equally satisfied no matter which follow-up program they were provided. From the Danish nationwide study of patient experiences with public hospitals, performed on an annual basis, we already knew that patients treated at this particular oncology department tend to give positive reports on satisfaction surveys [Citation44]. We hoped to maintain this high level of satisfaction while meeting the patients’ needs through individualizing follow-up care. Our findings indicate that this was achieved, since unmet needs occurred to the same extend in both groups and the proportion of patients reporting being satisfied or very satisfied, was above 88% at each time point. Yet, the strength of these statements must be interpreted with caution since this pilot trial only has power to detect a decline in satisfaction or increase in unmet needs of 20% or more between the groups (calculations performed with 80% power and a 95% significance level).

The present pilot randomized trial supports the utility of ePROs as a screening tool for individual care needs: Even though women in the intervention group spend less time on consultations, they had the same adherence to treatment and health related quality of life measurements as the standard care group. The fact that we could not identify any differences in self-reported quality of life in favor of the intervention may be due to insufficient power or ceiling effects [Citation30]. It is nevertheless important to note that women in IC, regardless of the significantly reduced number of consultations, did not suffer more health-related problems compared to SC.

The feasibility and acceptability of ePROs used for symptom surveillance has simultaneously been investigated within a Danish population of metastatic prostate cancer patients [Citation45] and during adjuvant chemotherapy in a Danish breast cancer population [Citation46,Citation47]. Both studies found that implementation of ePROs used actively as part of daily clinical practice is feasible in a Danish setting. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated within other Danish diagnostic groups that PRO assessment can be used to evaluate the need for a consultation during follow-up in chronic and malignant diseases and thereby customize the number of consultations needed to the individual [Citation48]. Evidence regarding the active use of ePROs during follow-up care after treatment for breast cancer is limited [Citation49], but advances within electronic software development continue to increase the usability and potential utility of ePROs. These data can be aggregated in clinical databases, used as prognostic markers, analyzed for epidemiological studies or fed back to patients alongside tailored self-management advice [Citation50–52]. Further research is this field is needed to examine the benefits of routine implementation of ePROs.

The strengths of this pilot trial include a design with prospectively collected ePROs, a high participation rate and high compliance with questionnaire completion. The recruitment from a single department is limiting for the generalizability to other settings and the sample size is underpowered to investigate all outcomes thoroughly. With 60 patients in each group there is only adequately power to detect a difference of approximately 20% or more in satisfaction, unmet needs and adherence to treatment. Furthermore the principal investigator was able to offer women in the intervention group continuity of follow-up care. This is likely to enhance their sense of psychological support which may have introduced bias. In a previous study of breast cancer care, continuity and health related quality of life were strongly associated [Citation53]. In the conduction of a larger scale, multi-center study, the design would have to take into account that the provision of care always depends on local conditions, rehabilitation services and the skills and engagement of the health professionals [Citation54–56]. Thus, satisfaction and unmet needs are expected to be heterogeneous at the time of enrollment and other primary outcomes could be considered.

In conclusion, women attending the ePRO based individualized follow-up were equally satisfied with their follow-up care as compared to women receiving SC. Unmet needs, adherence to treatment and self-reported health-related quality of life were similar in both groups, despite the use of fewer consultations in IC. We have found that the active use of ePROs to individualize follow-up care was feasible for the majority of patients in this population, but a more reliable outcome to evaluate efficacy is desirable for a larger scale trial.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (75.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. NORDCAN [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www-dep.iarc.fr/NORDCAN/DK/frame.asp.

- Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2019;5(1):66.

- Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG). Follow-up [Internet]. DBCG Guidel. 2015 [cited 2019 Oct 10]. p. Chapter 9, 6 pages. Available from: http://www.dbcg.dk/PDFFiler/Kap_9_Opfoelgning_og_kontrol-11.12.2015.pdf.

- Ruban PU, Wulff CN, Sperling CD, et al. Patient evaluation of breast cancer follow-up: a danish survey. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(1):99–104.

- Ellegaard MBB, Grau C, Zachariae R, et al. Women with breast cancer report substantially more disease- and treatment-related side or late effects than registered by clinical oncologists: a cross-sectional study of a standard follow-up program in an oncological department. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(3):727–736.

- Todd BL, Feuerstein M, Gehrke A, et al. Identifying the unmet needs of breast cancer patients post-primary treatment: the Cancer Survivor Profile (CSPro). J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):137–160.

- Davis LE, Bubis LD, Mahar AL, et al. Patient-reported symptoms after breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:1–11.

- Kadakia KC, Snyder CF, Kidwell KM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and early discontinuation in aromatase inhibitor-treated postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21(5):539–546.

- Sperling C, Sandager M, Jensen H, et al. Current organisation of follow-up does not meet cancer patients’ needs. Dan Med J. 2014;61:1–7.

- Palmer SC, Stricker CT, DeMichele AM, et al. The use of a patient-reported outcome questionnaire to assess cancer survivorship concerns and psychosocial outcomes among recent survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(8):2405–2412.

- Hansen DG, Larsen PV, Holm LV, et al. Association between unmet needs and quality of life of cancer patients: a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):391–399.

- Ellegaard M-B, Grau C, Zachariae R, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and unmet needs among breast cancer survivors in the first five years. a cross-sectional study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):314–320.

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(5):515–523.

- Danish Health Authority. Pakkeforløb for brystkraeft – til fagfolk. Breast cancer – guidelines to health professionals [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 19]. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2019/Pakkeforloeb-kraeft-2015-2019/Brystkraeft-2018/Pakkeforløb-for-brystkraeft-2018.ashx?la=da&hash=B0ECEC63750535FC707EF4EB06EF4C8958890F5E.

- Palli D, Russo A, Saieva C, et al. Intensive vs clinical follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: 10-year update of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1586–1586.

- Lin NU, Thomssen C, Cardoso F, et al. International guidelines for management of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) from the European School of Oncology (ESO)-MBC task force: surveillance, staging, and evaluation of patients with early-stage and metastatic breast cancer. Breast. 2013;22(3):203–210.

- Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder CF. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer: a review of recent research and policy initiatives. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(5):278–300.

- Chan EKH, Edwards TC, Haywood K, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice: a companion guide to the ISOQOL user’s guide. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(3):621–627.

- Aaronson N, Elliott T, Greenhalgh J, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice produced on behalf of the international society. Qual Life Res. 2015;21(8):1305–1314.

- Lavallee DC, Chenok KE, Love RM, et al. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes into health care to engage patients and enhance care. Health Aff. 2016;35(4):575–582.

- Rodkjaer LØ, Bregnballe V, Ågård AS. Handberg c LK. Patient-reported outcomes – a means of facilitating patient involvement. Sygeplejersken. 2015;115(12):77–80.

- Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:1–24.

- Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):714–724.

- Kluetz PG, O’Connor DJ, Soltys K. Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):267–274.

- Ishaque S, Karnon J, Chen G, et al. A systematic review of randomised controlled trials evaluating the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Qual Life Res. 2019;28(3):567–592.

- Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD, et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(34):4249–4255.

- Ong WL, Schouwenburg MG, Van Bommel ACM, et al. A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for breast cancer: The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) initiative. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):677–685.

- Gordon B-B, Chen RC. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivorship. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):166–173.

- Yang LY, Manhas DS, Howard AF, et al. Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(1):41–60.

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Adjuvant bisphosphonate treatment in early breast cancer: meta-analyses of individual patient data from randomised. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386:1353–1362.

- Danish Cancer Society. Patient Support [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.cancer.dk/international/patient-support/.

- Steine S, Finset A, Laerum E. A new, brief questionnaire (PEQ) developed in primary health care for measuring patients’ experience of interaction, emotion and consultation outcome. Fam Pract. 2001;18(4):410–418.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EORTC Quality of Life questionnaires [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Oct 10]. Available from: https://qol.eortc.org/.

- Aaronson NK, Te Velde A, Hopwood P, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;14:2756–2768.

- Giesinger JM, Kieffer JM, Fayers PM, et al. Replication and validation of higher order models demonstrated that a summary score for the EORTC QLQ-C30 is robust. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:79–88.

- Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3 ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. p. 1–78.

- Ramboll Management. SurveyXact User Manual [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Nov 14]. p. 1–304. Available from: https://view.publitas.com/ramboll/surveyxact-user-manual-12-8/page/1.

- By Ramboll. SurveyXact [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.surveyxact.com/about-us/.

- Ministry of Health. Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Nov 1]. Available from: http://en.nvk.dk/rules-and-guidelines/act-on-research-ethics-review-of-health-research-projects.

- Graf J, Simoes E, Wisslicen K, et al. Willingness of Patients with Breast Cancer in the Adjuvant and Metastatic Setting to Use Electronic Surveys (ePRO) depends on sociodemographic factors, health-related quality of life, disease status and computer skills. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76:535–541.

- Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1846–1858.

- PatientExperiences Center for Competence. Department of Oncology – Lillebaelt Hospital [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov 1]. Available from: https://patientoplevelser.dk/lup/landsdaekkende-undersoegelse-patientoplevelser-lup/lup-somatik-2018/supplerende-materiale-7.

- Baeksted C, Pappot H, Nissen A, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of electronic symptom surveillance with clinician feedback using the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) in Danish prostate cancer patients. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;1(1):1–11.

- Baeksted CW, Nissen A, Knoop A, et al. Handling of symptomatic adverse events in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy in a cluster randomized trial with electronic patient‐reported outcomes as intervention. Breast J. 2019;25(6):1295–1296.

- Pappot H, Baeksted C, Knoop A, et al. Routine surveillance for symptomatic toxicities with real-time clinician reporting in Danish breast cancer patients—Organization and design of the first national, cluster randomized trial using the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of Common Terminology C. Breast J. 2019;25(2):269–272.

- Schougaard LMV, Larsen LP, Jessen A, et al. AmbuFlex: tele-patient-reported outcomes (telePRO) as the basis for follow-up in chronic and malignant diseases. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):525–534.

- Riis CL, Bechmann T, Jensen PT, et al. Are patient-reported outcomes useful in post- treatment follow-up care for women with early breast cancer? A scoping review. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:117–127.

- Warrington L, Absolom K, Velikova G. Integrated care pathways for cancer survivors – a role for patient-reported outcome measures and health informatics. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):600–608.

- Sharma R, Shulman LN, James T. The future of quality improvement in breast cancer: patient-reported outcomes. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32(5):469–471.

- Kuijpers W, Groen WG, Oldenburg HS, et al. eHealth for breast cancer survivors: use, feasibility and impact of an interactive portal. JMIR Cancer. 2016;2(1):e3.

- Plate S, Emilsson L, Söderberg M, et al. High experienced continuity in breast cancer care is associated with high health related quality of life. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1–8.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Psychosocial/survivorship issues in breast cancer: are we doing better? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(1):335

- Brennan ME, Gormally JF, Butow P, et al. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(10):1899–1908.

- Santana MJ, Haverman L, Absolom K, et al. Training clinicians in how to use patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1707–1718.