Abstract

Background: The Dutch guidelines for esophageal and gastro-esophageal junction (GEJ) cancer recommend discussion of patients by a multidisciplinary tumor board (MDT). Despite this recommendation, one previous study in the Netherlands suggested that therapeutic guidance was missing for palliative care of patients with esophageal cancer. The aim of the current study was therefore to assess the impact of an MDT discussion on initial palliative treatment and outcome of patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer.

Material and methods: The population-based Netherlands Cancer Registry was used to identify patients treated for esophageal or GEJ cancer with palliative intent between 2010 and 2017 in 7 hospitals. We compared patients discussed by the MDT with patients not discussed by the MDT in a multivariate analysis. Primary outcome was type of initial palliative treatment. Secondary outcome was overall survival.

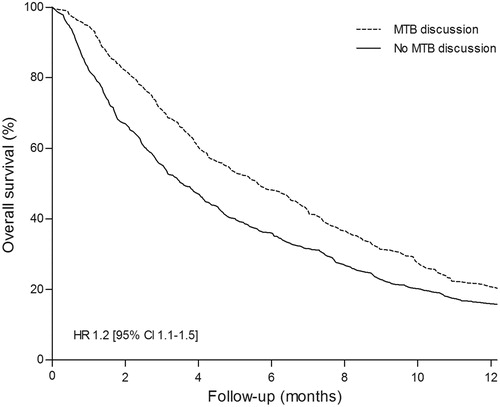

Results: A total of 389/948 (41%) patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer were discussed by the MDT before initial palliative treatment. MDT discussion compared to non-MDT discussion was associated with more patients treated with palliative intent external beam radiotherapy (38% vs. 21%, OR 2.7 [95% CI 1.8–3.9]) and systemic therapy (30% vs. 23%, OR 1.6 [95% CI 1.0–2.5]), and fewer patients treated with stent placement (4% vs. 12%, OR 0.3 [95% CI 0.1–0.6]) and best supportive care alone (12% vs. 33%, OR 0.2 [95% CI 0.1–0.3]). MDT discussion was also associated with improved survival (169 days vs. 107 days, HR 1.3 [95% CI 1.1–1.6]).

Conclusion: Our study shows that MDT discussion of patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer resulted in more patients treated with initial palliative radiotherapy and chemotherapy compared with patients not discussed by the MDT. Moreover, MDT discussion may have a positive effect on survival, highlighting the importance of MDT meetings at all stages of treatment.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the sixth most common cancer leading to death worldwide, with an estimated 572,000 new cases and 508,600 deaths in 2018 [Citation1]. When esophageal cancer is diagnosed, more than 50% of patients have either inoperable tumors or radiographically visible metastases [Citation2]. In these patients, palliative treatment may be indicated to improve quality of life and possibly survival [Citation3,Citation4].

Available tumor-specific palliative options for esophageal or gastro-esophageal (GEJ) cancer include systemic therapy and/or radiotherapy, or stent placement for dysphagia [Citation3,Citation5]. Best supportive care (BSC), as an integral part of palliative treatment, may be the only option for patients who are not eligible for a tumor-specific treatment [Citation6]. Given the wide variation in palliative treatment options, Dutch guidelines for esophageal cancer recommend that treatment of patients should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team of care providers [Citation7].

Case-by-case discussion of patients in a multidisciplinary tumor board (MDT) meeting has been shown to improve clinical outcome in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer [Citation8]. In esophageal cancer, a study showed that MDT discussion of patients eligible for curative treatment changed treatment plans in more than one-third of patients [Citation9]. In addition, one recent study found that younger patients and patients with advanced stage upper gastrointestinal cancer were less likely to be referred for MDT discussion [Citation10].

Until now, the impact of an MDT discussion has not been assessed in patients requiring a palliative treatment option for esophageal or GEJ cancer. Moreover, one previous study in the Netherlands suggested that for palliative care of patients with esophageal cancer no clear therapeutic guidance was available [Citation11]. Therefore, this study aimed to study how many palliative patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer are discussed by a multicenter MDT and to assess its impact on initial palliative treatment and outcome compared with non-MDT discussed patients.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included patients from 7 centers with esophageal or GEJ cancer who were treated with palliative intent. Patients were identified from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), a population-based database covering the total population of patients with any type of cancer in the Netherlands. The NCR is directly linked to the pathological archive which comprises all histologically confirmed cancer diagnoses. Data on vital status were obtained from the Dutch Personal Records Database.

Patients diagnosed with esophageal or GEJ cancer between January 2010 and December 2017, and treated with palliative therapy were included in this study. Patients were excluded when: (1) the primary diagnosis of esophageal or GEJ cancer was made outside the participating centers; (2) patients had undergone previous treatment of esophageal or GEJ cancer with curative intent; (3) patients died within 7 days after histological diagnosis; (4) palliative treatment was indicated primarily for cancer other than esophageal or GEJ cancer; (5) data on palliative treatment was missing.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board (IRB) of all participating centers.

Data collection and definitions

The NCR provided data on tumor characteristics, palliative treatment and survival until December 31, 2017. Additionally, in adherence to our pre-specified study definitions, we discussed the electronic medical records of all included patients to add missing data and to collect Supplementary data regarding hospital of diagnosis, patient and palliative treatment characteristics, MDT discussion and follow-up.

Esophageal cancer included cancer of the esophagus (C15.0–C15.9) and GEJ (C16.0) [Citation12]. Palliative treatment was indicated in patients with distant metastases (i.e. Tany, Nany, M1; according to the Tumor Node Metastasis [TNM] staging system), inoperable disease or in case the patient refused treatment with curative intent. Inoperable disease was defined as no possible curative treatment (neoadjuvant chemoradiation with esophagectomy[Citation13]; or definitive chemoradiation[Citation14]) due to locally advanced tumor (TNM: T4b, Nany, M0) or a poor medical condition of the patient. Tumor histology and localization were recorded according to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases for Oncology [Citation15]. For tumor staging, the 7th and 8th edition (for diagnoses between 2010–2016 or in 2017, respectively) of the American Joint Committee of Cancer staging manual for patients with esophageal and GEJ cancer was used [Citation12,Citation16]. Lesion size was measured from the diagnostic endoscopy report. Performance status was scored according to the Karnofsky score or, when possible, inferred from the physician’s documentation [Citation17].To assess comorbidity, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used [Citation18]. We assumed that if comorbidity was not documented in the patients’ medical records, the patient indeed did not have comorbidity. For each patient, the comorbidity score was calculated by adding up the comorbid conditions with the exclusion of esophageal cancer. For ease of the application, patients were stratified by the following categories: 0–1 points, 2–3 points, 4–5 points and 6 or more points. As all patients had esophageal cancer, we excluded ‘cancer’ from the comorbidity score calculation.

Initial palliative treatment was defined as first-line treatment for esophageal or GEJ cancer without curative intent. Palliative treatment included external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), intra-luminal brachytherapy (ILBT), stent placement, systemic therapy or BSC. Systemic therapy included chemotherapy and targeted therapy. BSC included a non-tumor-specific treatment (e.g. psychosocial support, analgesics, antiemetic drugs, nutritional support, corticosteroids, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, placement of a naso-enteral feeding tube). As this study assessed retrospectively collected data, treatments were not standardized. Therefore, a variety of different radiotherapy schedules, chemotherapeutic agents and types of esophageal stents were used during the study period.

Dysphagia was scored according to Ogilvie (grade 0 = ability to eat a normal diet; grade 1 = ability to eat some solids; grade 2 = ability to swallow semisolids only; grade 3 = ability to swallow liquids only; grade 4 = complete dysphagia for liquids) [Citation19].

Multicenter multidisciplinary tumor board

An MDT meeting in which patients are discussed by a team of dedicated specialists is recommended by the Dutch guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal and gastric malignancies [Citation7]. In the Eastern part of the Netherlands, the MDT is centralized and consists of a team of specialists from multiple centers that are dedicated to the management of esophageal, GEJ and stomach cancer. During each meeting, which is held once a week, a team of gastroenterologists, oncologic surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists and radiologists discusses all new patients. Clinicians from the regional hospitals are invited to refer patients to the MDT to receive expert-opinion based recommendations on clinical management. After a case-by-case discussion, the consensus is documented and reported to the treating physicians. Patients were referred to the MDT at the discretion of the treating physician.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

The primary outcome was type of initial palliative treatment including: (1) EBRT; (2) combination of EBRT and ILBT; (3) systemic therapy; (4) stent placement; or (5) BSC. Treatment was reported missing if no data on type of initial palliative treatment was documented in the patients’ medical record. Secondary outcome was overall survival, i.e. the number of days alive after diagnosis of esophageal cancer. To adjust for immortal time bias, we reduced the survival time by 7 days for patients not discussed by the MDT. The treatment interval was defined as the time from diagnosis to initial treatment, i.e. the number of days between histological diagnosis and initial palliative treatment.

Chi-square and t tests were used to assess baseline and outcome differences between patient groups and participating centers in categorical and continuous data, respectively. Survival was calculated from the date of histological diagnosis to the date of death, plotted using the Kaplan–Meier estimator and compared using a log-rank test.

For the analysis of the primary outcome, we used a multivariate multinomial logistic regression model, while adjusting for baseline parameters that differed significantly (p-value of <.2) in the univariate analysis. We calculated the odds of receiving an initial palliative treatment (i.e. EBRT or EBRT in combination with ILBT or systemic therapy or stent placement) rather than BSC. Baseline parameters with >5% of missing data were excluded from the multivariate analysis. Multivariate multinomial logistic regression was performed with backward stepwise elimination until all remaining variables reached a p-value of <.05. Results were expressed as percentages, odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI.

For the multivariate analysis of the secondary outcome, we used a Cox proportional hazard model to compare survival of patients. To adjust for confounding, we selected potential confounders (e.g. comorbidity) and parameters that have previously been identified as predictors for survival, i.e. clinical TNM stage group, tumor localization, location of lymph node and distant metastasis and number of metastatic sites [Citation20]. Multivariate Cox regression was performed while correcting for parameters that differed significantly (p-value of <.2) at baseline and hospital of diagnosis. Results were expressed as medians (95% confidence intervals [CI]), hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CI

A two-tailed p-value of <.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses. SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY) was used for study analysis.

Results

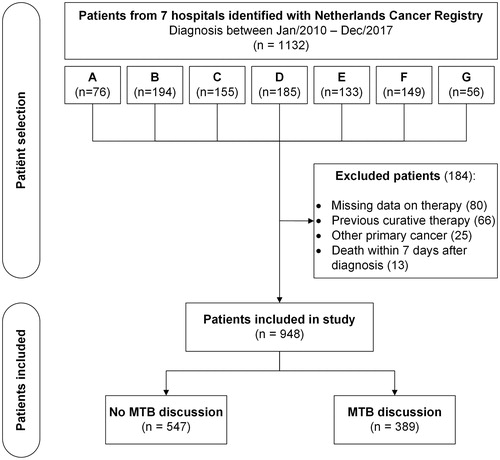

A total of 1132 patients from 7 centers were identified from the NCR, of whom 948 met the inclusion criteria. The baseline characteristics of included patients and differences between patients discussed by the MDT and patients who were not discussed are shown in . Patients had a mean age of 70 ± 12 years, were predominantly men (73%) and 74% (n = 705) were diagnosed with stage IV esophageal or GEJ cancer. At diagnosis, 646 (68%) patients had adenocarcinoma and 489 (52%) reported symptoms of dysphagia. In 671 (73%) patients, the reason for initial palliative treatment was the presence of distant metastasis, followed by inoperable disease in 198 (22%) patients. A total of 52 (6%) patients were treated with initial palliative treatment because they refused treatment with curative intent. shows the study flow diagram of patient inclusion.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram of selection of patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer. MDT: multidisciplinary tumor board.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and differences between groups of patients treated with initial palliative treatment for esophageal cancer.

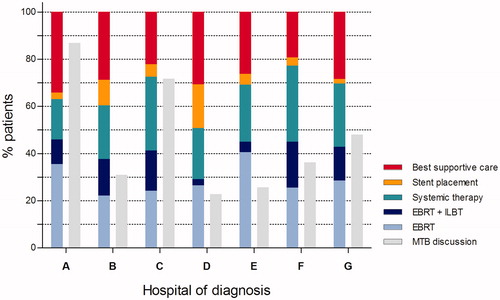

Prior to selection of palliative treatment, 389 (41%) patients were discussed by the MDT. The yearly incidence of patients discussed by the MDT increased steadily from 35 (27%) cases in 2010 to 78 (58%) cases in 2017. The incidence of patients discussed by the MDT differed significantly between the participating centers (p < .001; ). Median time from diagnosis until start of initial palliative treatment was 24 days (IQR 13-37). This interval was significantly longer in patients discussed by the MDT, when compared with patients who were not discussed, 30 days (IQR 19–41) vs. 20 days [IQR 9–34]), respectively (p < .001).

Figure 2. Distribution of initial palliative treatment modalities and rate of patients discussed by a multidisciplinary tumor board, stratified by hospital of diagnosis. EBRT: external beam radiotherapy; ILBT: intra-luminal brachytherapy; MDT: multidisciplinary tumor board.

Initial palliative treatment

Of all 948 patients, 419 (44%) were initially treated for dysphagia with palliative radiotherapy (n = 340, 81%) or esophageal stent placement (n = 79, 19%). Palliative radiotherapy consisted of EBRT in 221 patients (65%), ILBT in 28 (8%) or a combination of both in 91 (27%). Furthermore, a total of 242 (26%) patients were initially treated with palliative systemic therapy and 225 (24%) were managed with BSC only. In 71 (7%) patients, type of initial treatment was not documented (i.e. missing) in the patients’ medical records.

Differences in number of patients and odds of receiving an initial treatment modality rather than BSC between patients discussed by the MDT and patients not discussed by the MDT are shown in . After multivariate analysis, discussion by the MDT was associated with a higher number of patients treated with EBRT (35% vs. 19%, OR 6.9 [95% CI 3.9–12.4]), a combination of EBRT and ILBT (16% vs. 7%, OR 9.6 [95% CI 4.6–20.0]) and systemic therapy (32% vs. 26%, OR 4.7 [95% CI 2.6–8.4]), when compared with non-MDT discussed patients. MDT discussion was not associated with a difference in odds of receiving stent placement (3% vs. 12%, OR 1.8 [95% CI 0.7–4.3]). In addition, unadjusted analysis (chi-square) showed that more patients not discussed by the MDT were treated with BSC (37% vs. 13%, <.001) or stent placement (12% vs. 3%, <.001).

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate analysis of the impact of multidisciplinary tumor board discussion on initial palliative treatment versus best supportive care and survival of patients with esophageal cancer.

shows the differences in MDT discussion rate and initial palliative treatments between the 7 participating centers. Univariate analysis showed a significant difference between centers with respect to initial treatment with EBRT (p = .010), a combination of EBRT and ILBT (p < .001), systemic therapy (p = .039) and stent placement (p < .001). No difference was observed in management with BSC only (p = .757).

Survival

Median survival of all 948 patients was 128 days (95% CI 115–141). The survival difference between patients discussed by the MDT and patients who were not discussed is shown in and . Univariate analysis showed that MDT discussion was associated with better survival, when compared with patients not discussed by the MDT (163 vs. 106 days, HR 1.2 [95% CI 1.1–1.4]). After adjusting for confounders in multivariate analysis, the observed survival difference remained statistically significant (HR 1.2 [95% CI 1.1–1.5]).

Discussion

This population-based study assessed the association of MDT discussion and type of initial palliative treatment of patients with esophageal or GEJ cancer. Patients discussed by the MDT were more frequently treated with palliative radiotherapy and systemic therapy rather than BSC only. Furthermore, our study suggested that MDT discussion before initiation of treatment was associated with a 2-month (54%) longer survival, when compared with non-MDT discussed patients.

A recent systematic review of 27 studies showed that MDT discussion of patients impacts clinical management in many fields of oncology [Citation8]. Moreover, in some types of cancer, it has been shown that MDT discussion was associated with better survival [Citation21–23]. In esophageal cancer, studies have mainly investigated the impact of MDT discussion on clinical management of patients eligible for curative treatment [Citation9,Citation24–27]. It was concluded that discussing patients in an MDT changed therapeutic decisions in a considerable number of patients. To date, no studies have investigated the effect of MDT discussion on therapeutic decisions and survival of patients with incurable esophageal or GEJ cancer.

The present study suggests that MDT involvement before initiation of palliative treatment was associated with improved survival. The observed differences in initial radiation and systemic therapy may explain this survival difference as these modalities are independently associated with improved survival [Citation3,Citation20]. In further support of this explanation, we found that patients not discussed by the MDT were more frequently treated with stent placement or BSC only, which are purely palliative treatments and not associated with survival improvement [Citation20]. Nonetheless, despite adjustment for potential confounders and participating center, it may well be that the survival difference between patient groups has been the result of patient selection based on prognostic factors that are not in the database.

Since 2006, Dutch guidelines recommend MDT discussion of all patients with a new diagnosis of esophageal cancer before initiation of therapy [Citation7,Citation9]. Despite this advice, we observed a relatively low rate (41%) of palliative patients discussed by the MDT before initiation of palliative treatment over an 8-year study period. This may be explained by two factors. First, as MDT-discussed patients were younger, in a lower TNM stage group and had fewer liver metastases, it seems likely that clinicians more frequently referred patients with better prognostic features to the MDT. A recent nationwide Dutch population-based study reporting on seven different tumor types also concluded that patients discussed by an MDT were younger and in a lower TNM stage group [Citation10]. It may well be that clinicians considered patients with more advanced disease unlikely to benefit from a discussion in the MDT. Moreover, referral may also lead to a delay in the decision-making process, as was also shown in this study. Second, we observed that referral to the MDT differed significantly between participating centers (), suggesting that referral of patients was also influenced by center- or physician-related factors.

Findings from this study may have implications for clinical practice. As we found that referral to the MDT was associated with changes in initial palliative treatment, we suggest that clinicians consider referral of all palliative patients with esophageal cancer to the MDT, irrespective of the patients’ prognosis. To improve MDT referral rates, we propose that clinicians discuss the results of the present study in a regional meeting to raise awareness among involved care providers on the importance of an MDT discussion in palliative patients with esophageal cancer.

The main strength of this study is that we used a population-based and prospectively maintained cancer registry to identify and assess the vast majority of patients in a well-circumscribed region. This real-world evidence can therefore be reliably translated to daily clinical practice. Another strength is that we double-checked and added data from the cancer registry by comprehensively reviewing the patients’ electronic medical records following our pre-specified study protocol.

Possible limitations include that selection of patients for MDT discussion may have increased the risk of bias. Baseline differences between patient groups () suggest that clinicians particularly selected patients based on several prognostic factors to be discussed by the MDT. In addition, clinicians’ preferences likely will have influenced selection of palliative treatment, as is shown by treatment differences between participating hospitals.

Second, retrospective assessment of medicals records resulted in missing information on the performance status in almost two-thirds (65%) of patients. Consequently, we could not adjust for performance status in the multivariate survival analysis. Moreover, as performance status has been shown to be an important predictor for survival in patients with esophageal cancer, addition of this variable to the multivariate model would likely have resulted in a more reliable reflection of the impact of MDT discussion on treatment selection and outcome [Citation28].

Finally, we could not assess the proposed positive impact of MDT discussion on patients’ quality of life. From the patients’ perspective, improvement of prognosis while maintaining a good quality of remaining life may be the most important outcome of palliative care and this should prospectively be investigated in future studies.

In conclusion, this population-based multicenter cohort study showed that patients discussed by an MDT were more likely treated with palliative radiation and systemic therapy rather than receiving BSC, when compared with patients not discussed. We hypothesize that these treatment differences may have resulted in the improved survival of patients discussed by an MDT. Therefore, our findings suggest that esophageal and GEJ cancer patients at all stages of the disease should be discussed in an MDT meeting before initiation of treatment. Additional prospective studies are required to assess the impact of an MDT discussion on clinical outcome.

| Abbreviations | ||

| MDT | = | multidisciplinary tumor board |

| NCR | = | Netherlands cancer registry |

| IRB | = | institutional review board |

| TNM | = | tumor node metastasis |

| GEJ | = | gastro-esophageal junction |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

| AJCC | = | American Joint Committee of Cancer |

| EBRT | = | external beam radiotherapy |

| ILBT | = | intra-luminal brachytherapy |

| BSC | = | best supportive care |

Disclosure statement

RHAV has received research grants from Roche and Bristol–Myers Squibb. RHAV declares no personal conflicts of interest. PDS has received research grants from Boston Scientific, Cook Medical and MI-Tech for some of the studies referenced in this review, and is on the advisory board of Ella-CS. PDS declares no personal conflicts of interest. All other authors have nothing to disclose and no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–1953. 15

- Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2241–2252.

- Janmaat VT, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A, et al. Palliative chemotherapy and targeted therapies for esophageal and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD004063.

- Al-Batran SE, Ajani JA. Impact of chemotherapy on quality of life in patients with metastatic esophagogastric cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(11):2511–2518.

- van der Bogt RD, Vermeulen BD, Reijm AN, et al. Palliation of dysphagia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;36-37:97–103.

- Glimelius B, Ekstrom K, Hoffman K, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(2):163–168.

- Siersema PD, Rosenbrand CJ, Bergman JJ, et al. [Guideline 'Diagnosis and treatment of oesophageal carcinoma']. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006;150(34):1877–1882.

- Pillay B, Wootten AC, Crowe H, et al. The impact of multidisciplinary team meetings on patient assessment, management and outcomes in oncology settings: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;42:56–72.

- van Hagen P, Spaander MC, van der Gaast A, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary tumour board meeting for upper-GI malignancies on clinical decision making: a prospective cohort study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18(2):214–219.

- Walraven JEW, Desar IME, Hoeven van der JJM, et al. Analysis of 105.000 patients with cancer: have they been discussed in oncologic multidisciplinary team meetings? A nationwide population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2019;121:85–93.

- Opstelten JL, de Wijkerslooth LR, Leenders M, et al. Variation in palliative care of esophageal cancer in clinical practice: factors associated with treatment decisions. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(2):1–7.

- Rice TW, Patil DT, Blackstone EH. 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging of cancers of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: application to clinical practice. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6(2):119–130.

- Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1090–1098.

- Gwynne S, Hurt C, Evans M, et al. Definitive chemoradiation for oesophageal cancer–a standard of care in patients with non-metastatic oesophageal cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol. 2011;23(3):182–188.

- Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al. International classification of diseases for oncology. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

- Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(7):1721–1724.

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation ofchemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Macleod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949. p. 191–205.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Ogilvie AL, Dronfield MW, Ferguson R, et al. Palliative intubation of oesophagogastric neoplasms at fibreoptic endoscopy. Gut. 1982;23(12):1060–1067.

- van den Boorn HG, Abu-Hanna A, Ter Veer E, et al. SOURCE: a registry-based prediction model for overall survival in patients with metastatic oesophageal or gastric cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(2):187.

- MacDermid E, Hooton G, MacDonald M, et al. Improving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary team. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(3):291–295.

- Bydder S, Nowak A, Marion K, et al. The impact of case discussion at a multidisciplinary team meeting on the treatment and survival of patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Intern Med J. 2009;39(12):838–841.

- Blay JY, Soibinet P, Penel N, et al. Improved survival using specialized multidisciplinary board in sarcoma patients. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(11):2852–2859.

- Bumm R, Feith M, Lordick F, et al. Impact of multidisciplinary tumor boards on diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer. Eur Surg. 2007;39(3):136–140.

- Schmidt HM, Roberts JM, Bodnar AM, et al. Thoracic multidisciplinary tumor board routinely impacts therapeutic plans in patients with lung and esophageal cancer: a prospective cohort study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(5):1719–1724.

- Freeman RK, Van Woerkom JM, Vyverberg A, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary thoracic malignancy conference on the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(4):1239–1243.

- Koeter M, van Steenbergen LN, Lemmens VE, et al. Hospital of diagnosis and probability to receive a curative treatment for oesophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(10):1338–1345.

- Amdal CD, Jacobsen AB, Falk RS, et al. Improved treatment decisions in patients with esophageal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(10):1286–1294.