Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer type and the second most common cancer-related death worldwide [Citation1]. High incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer and effective screening tools have motivated nationwide immunochemical fecal occult blood test (iFOBT)-based colorectal cancer screening in many countries, including Denmark [Citation1,Citation2]. The benefit from the program depends largely on the participation rates and despite Danish free-of-charge screening, almost 40% choose not to participate [Citation3].

Known facilitators of colorectal cancer screening include older age, high socioeconomic position, being married, Western ethnicity, and metropolitan residence [Citation4–8].

Individuals who have frequent contact with the general practitioners and dentists have been found more likely to participate in colorectal cancer screening [Citation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation10]. Whether this applies to other medical specialties and in a Danish context, is unknown. Studies have shown that the use of psychiatrists is associated with nonparticipation for women in cervical cancer and breast cancer screening [Citation11–14], but whether this association is present in colorectal cancer screening, which includes both men and women, also remains unknown.

To bring new insight into how non-participants in colorectal cancer screening could be identified and targeted, we assess associations between the use of primary health care and participation in colorectal cancer screening by 18 different medical specialties in Denmark; with special emphasis on visits to general practitioners, dentists, and psychiatrists.

Material and methods

Study design and patient selection

The study was designed as a register-based cross-sectional study including all individuals aged 50–74 years who were invited to the Danish, iFOBT-based colorectal cancer screening program between March 2014 and December 2017 (and who were not attending intensified colonoscopic surveillance programs) [Citation15]. The specific exclusion criteria (i.e., individuals aware of familiarly increased risk of colorectal cancer) and a flow chart are described in the supplemental material. The outcome of interest was participation in the noninvasive iFOBT-screening, defined as whether the individuals returned their sample in the prepaid return envelope within 4.5 months after the invitation date [Citation16].

The study was granted acceptance from the Danish Data Protection Agency. According to Danish regulations, anonymized registry studies are not subject to ethical review.

Data extraction

Individual-based data from five national Danish registries were merged via pseudonymized personal identification numbers obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) [Citation17]. Information on age and sex was obtained from CRS. Data on visits to health professionals were extracted from the Danish National Health Service Register (NHSR) [Citation18]. Data on returned fecal samples were from the Danish Colorectal Cancer Screening Database (DCCSD) [Citation15], and data on ethnicity, civil status, education, and income were obtained from Statistics Denmark [Citation19]. Data on intensified colonoscopic surveillance, genetic testing, and knowledge of increased familial colorectal cancer risk were extracted from the Danish Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) register [Citation20].

All data were uploaded to Statistics Denmark for data management and analyses.

Definitions

Visits to health professionals were evaluated for 18 medical specialties. The specific definition of visits can be found in the supplemental material. Within a window of 2 years preceding colorectal cancer screening invitation, individuals were categorized as having no visits or any visits. Subset analyses were performed in three specialties of interest, i.e., general practitioners, dentists, or psychiatrists. In here, the visits were categorized into subgroups of no visits, 1–4, 5–8, 9–12 and >12 visits for general practitioners and as no visits, 1, 2, 3, 4 and >4 visits for dentists and psychiatrists.

Age was categorized into five-year intervals ranging from 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69 and 70–74 years. Ethnicity was categorized into Danish, Western immigrants and non-Western immigrants. Civil status was categorized into Married, Widow, Divorced and Single. Education was categorized into basic/high school, vocational, and higher education. Income was categorized into the 20th, 40th, 60th and 80th percentiles of the age- and sex-specific income distributions [Citation21].

For exclusion, individuals aware of their familiarly increased risk of colorectal cancer were defined as having received a genetic counseling session, having an identified genetic variant predisposing to colorectal cancer, having received written surveillance recommendations, or having completed at least one screening colonoscopy.

Statistics

Participation rates were defined as the proportion of participating individuals compared to the full study population. Differences in participation rates by visits to health professionals were tested using a chi-squared test. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds of participation adjusted for sex, age, education, income, ethnicity, civil status, and year of invitation. We used complete case analyses in the fully adjusted models. Relative effects were reported as odds ratios and presented with 95% confidence intervals. p-Values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software package version 3.5.1.

Results

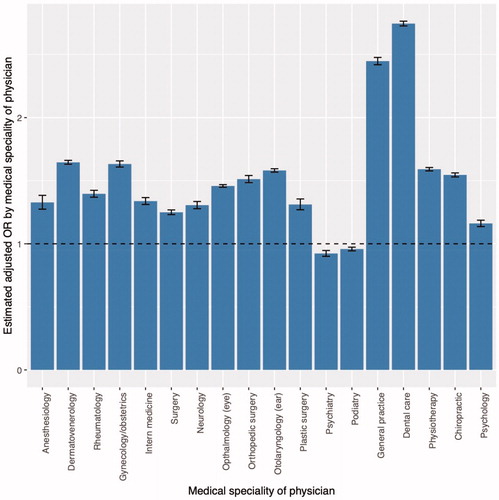

A total of 1,909,662 individuals invited for colorectal cancer screening, were included in the analyses, and of these, 1,198,084 (62.7%) participated in the screening. Participation was associated with female sex, older age, high educational levels and income, Danish ethnicity, and being married (Table 1a in the supplemental material). Participation was also associated with the use of health professionals (Table 2a in the supplemental material). Compared to no visit to the medical specialties assessed, increased odds of participation was found in individuals with any visit to the medical specialty. This was found for 16 medical specialties (highest within individuals visiting general practitioners or dentists) whereas decreased odds were observed in individuals with any visits to psychiatrists or podiatrists ().

Figure 1. Adjusted* odds ratios of participation by any visits (≥1 in the 2-year period compared to no visits). *Adjusted for sex, age, education, income, ethnicity, civil status, and year of invitation.

Visits to general practitioners

Colorectal cancer screening participation was associated with the number of visits to general practitioners with increasing odds ratios linked to an increasing number of visits (). Thus, individuals with 9–12 visits to general practitioners were most likely to participate in screening (OR: 2.96, 95% CI: 2.91–3.00, p < .001) when compared with individuals with no visits. Any visit to general practitioners was a significant facilitator with an OR of 1.99 (95% CI: 1.96–2.02, p < .001) for individuals with 1–4 visits compared to those with no visits.

Table 1. Unadjusted and adjusted* odds ratios of participation in the Danish colorectal cancer screening by visits to a general practitioner, dentist, and psychiatrist.

Visits to dentists

Participation was also associated with visits to a dentist with the highest odds ratio of participation among the individuals with four visits. Even one visit to the dentist was significantly associated with colorectal cancer screening participation with an OR of 1.87 (95% CI: 1.85–1.89, p < .001) compared to individuals with no visits ().

Visits to psychiatrists

The group of patients who had any contact with a psychiatrist in the previous two years constituted 1.33% of the total population. The participation proportions were highest among individuals with no contact to a psychiatrist (62.8%), and lowest among individuals with one visit (51.8%) (Table 2a in the supplemental material), corresponding to an OR of 0.81 (95%CI: 0.75–0.87, p < .001) compared to those with no visits (). Interestingly, individuals with more than three visits to a psychiatrist were no longer significantly different in participation compared to individuals with no visits ().

Discussion

This study is the first to describe associations between the use of a wide range of primary health care specialties and participation in colorectal cancer screening. The use of primary health care professionals was generally associated with higher participation, while the use of psychiatrists was associated with less participation in colorectal cancer screening. One to four health care visits to the general practitioner or one visit to the dentist was a positive facilitator of colorectal cancer screening, which is consistent with findings from previous studies [Citation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation10].

The screening participation in the groups that did not use general practitioners or dentists was approximately 40% which is markedly lower than any of the subgroups on sociodemographic predictors in colorectal cancer screening participation reported in previous studies [Citation3,Citation22]. The participation rate was not influenced by demographic and socioeconomic factors suggesting that health behavior (that does not include regular visits to general practitioners and dentists) influences screening participation above and beyond that explained by the well-known predictors. Therefore, the associations could be partially due to invitees’ attitudes, anxieties regarding test results, pain, discomfort and embarrassment during the follow-up colonoscopy, and health professionals’ attitudes and endorsement of screening [Citation6,Citation23–27].

Increasing participation rates were linked to an increasing number of visits to general practitioners or dentists which is in accordance with previous studies showing that individuals with an updated influenza vaccination program, regular cholesterol checks, or who follow other cancer-preventive screenings, are more likely to participate in colorectal cancer screening programs [Citation28,Citation29]. The underlying reason for the positive effect of contact with the general practitioner remains unknown. However, some general practitioners likely endorse their patients to participate in colorectal cancer screening which may have a positive effect [Citation23,Citation27]. Interestingly, for individuals with a higher number of visits (>12 for general practice and >4 for dentist visits) the association decreases (though still significant). The relatively high number of health care visits per two-year could be explained by comorbidities or severe illness in the individuals and hence their motivation to participate in a cancer screening program seems unimportant and unnecessary.

Regarding visits to psychiatrists, we observed significant associations between nonparticipation in screening and having had few visits with a psychiatrist in the preceding two years. This is consistent with tendencies observed in both cervical and breast cancer screening participation [Citation11–14]. The participation proportion of these individuals was markedly lower than the national participation proportion and other demographic and socioeconomic subgroups reported in this study. One explanation could be that individuals with severe psychiatric disorders may deal with symptoms accompanying their disease and coping with everyday consequences of it. This may not leave much energy for considering actions potentially benefitting long-term health as participating in colorectal cancer screening [Citation11,Citation30]. Supportive for this hypothesis is our finding that the odds of participating was higher for individuals who had used a psychologist during the preceding two years compared to individuals who had visited a psychiatrist.

The findings from this study can be used when considering targeted interventions toward increasing screening participation. One such intervention could be counseling by a general practitioner about general health behavior, including screening, specifically targeting individuals with long periods without contact with the health care system.

A major strength of this study was the large dataset and use of the register-based approach combining data from high-quality Danish registers based on mandatory reporting and with almost complete nationwide coverage. The results are generalizable to the Danish population since the data used covers the entire nation. Whether the results apply to other countries with similar screening programs is likely, but cultural differences may cause country-specific variations.

The design of the study minimizes the risk of information bias and misclassification. The data material ensured precise risk estimates and low risk of selection bias because of the minimal exclusion proportion. A weakness of this study was the potential risk of confounding from unmeasured confounders. We did not have information on the place of residence, behavioral, and psychological factors [Citation22]. The potential influence of these factors should be assessed in future research. However, we had valid data on sex, age, education, income, ethnicity, civil status, and year of invitation, and we adjusted for these factors in the analyses. We assume that the included potential confounders account for the most important potential confounding.

Conclusion

Participation in colorectal cancer screening in Denmark is associated with the use of a wide range of primary health care specialists; the more visits the higher participation. However, the use of psychiatrists within two years before an invitation to colorectal cancer screening showed significantly lower participation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (49.7 KB)Disclosure statement

After completing the work on the review and near to its final publication, KKA started working at Astra Zeneca.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, et al. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterology. 2008;103(6):1541–1549.

- Deding U, Henig AS, Salling A, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of participation in colorectal cancer screening. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(8):1117–1124.

- Wools A, Dapper EA, de Leeuw J. Colorectal cancer screening participation: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(1):158–168.

- Gimeno García AZ. Factors influencing colorectal cancer screening participation. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–483417.

- Goodwin BC, March S, Ireland M, et al. Geographic variation in compliance with Australian colorectal cancer screening programs: the role of attitudinal and cognitive traits. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19:4957.

- Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–394.

- van Jaarsveld CHM, Miles A, Edwards R, et al. Marriage and cancer prevention: does marital status and inviting both spouses together influence colorectal cancer screening participation? J Med Screen. 2006;13(4):172–176.

- von Euler-Chelpin M, Brasso K, Lynge E. Determinants of participation in colorectal cancer screening with faecal occult blood testing. J Public Health (Oxf). 2010;32(3):395–405.

- Menvielle G, Dugas J, Richard J-B, et al. Socioeconomic and healthcare use-related determinants of cervical, breast and colorectal cancer screening practice in the French West Indies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2018;27(3):269–273.

- Jensen LF, Pedersen AF, Bech BH, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and non-participation in breast cancer screening. Breast. 2016;25:38–44.

- Eriksson EM, Lau M, Jönsson C, et al. Participation in a Swedish cervical cancer screening program among women with psychiatric diagnoses: a population-based cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):313–313.

- Yee EFT, White R, Lee S-J, et al. Mental illness: is there an association with cancer screening among women veterans? Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4):S195–S202.

- Martens PJ, Chochinov HM, Prior HJ, et al. Are cervical cancer screening rates different for women with schizophrenia? A Manitoba population-based study. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(1):101–106.

- Thomsen MK, Njor SH, Rasmussen M, et al. Validity of data in the Danish Colorectal Cancer Screening Database. CLEP. 2017;9:105–111.

- Njor SH, Friis-Hansen L, Andersen B, et al. Three years of colorectal cancer screening in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;57:39–44.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549.

- Andersen JS, Olivarius NDF, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):34–37.

- Thygesen L. The register-based system of demographic and social statistics in Denmark. SJU. 1995;12(1):49–55.

- Lindberg LJ, Ladelund S, Frederiksen BL, et al. Outcome of 24 years national surveillance in different hereditary colorectal cancer subgroups leading to more individualised surveillance. J Med Genet. 2017;54(5):297–304.

- Andersen KK, Olsen TS. Risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in occult and manifest cancers. Stroke. 2018;49(7):1585–1592.

- Larsen MB, Mikkelsen EM, Rasmussen M, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of nonparticipants in the Danish colorectal cancer screening program: a nationwide cross-sectional study. CLEP. 2017;9:345–354.

- Goodwin BC, Ireland MJ, March S, et al. Strategies for increasing participation in mail-out colorectal cancer screening programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):257–257.

- Berkowitz Z, Hawkins NA, Peipins LA, et al. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):307–314. 2007/12/07.

- Consedine NS, Ladwig I, Reddig MK, et al. The many faeces of colorectal cancer screening embarrassment: preliminary psychometric development and links to screening outcome. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16(3):559–579.

- Buchman S, Rozmovits L, Glazier RH. Equity and practice issues in colorectal cancer screening. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(4):e186–e193.

- Goodwin BC, Crawford-Williams F, Ireland MJ, et al. General practitioner endorsement of mail-out colorectal cancer screening: the perspective of nonparticipants. Transl Behav Med. 2019. DOI:10.1093/tbm/ibz011

- Shapiro JA, Seeff LC, Nadel MR. Colorectal cancer-screening tests and associated health behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(2):132–137.

- Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Tabbarah M, et al. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening in diverse primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:116.

- Fujiwara M, Inagaki M, Nakaya N, et al. Cancer screening participation in schizophrenic outpatients and the influence of their functional disability on the screening rate: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71(12):813–825.