Abstract

Introduction

Surrogate markers of the host immune response are not currently included in AJCC staging for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), and have not been consistently associated with clinical outcomes. We performed an analysis of a large national database to investigate tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) grade as an independent predictor of overall survival (OS) for patients with MCC and to characterize the relationship between TIL grade and other clinical prognostic factors.

Material and methods

The NCDB was queried for patients with resected, non-metastatic MCC with known TIL grade (absent, non-brisk and brisk). Multivariable Cox regression modeling was performed to define TIL grade as a predictor of OS adjusting for other relevant clinical factors. Multinomial, multivariable logistic regression was performed to characterize the relationship between TIL grade and other clinical prognostic factors. Multiple imputation was performed to account for missing data bias.

Results

Both brisk (HR 0.55, CI 0.36–0.83) and non-brisk (HR 0.77, CI 0.60–0.98) were associated with decreased adjusted hazard of death relative to absent TIL grade. Adverse clinical factors such as 1–3 positive lymph nodes, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and immunosuppression were associated with increased likelihood of non-brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade (p values <.05). Extracapsular extension (ECS) was associated with decreased likelihood of brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade (p<.05).

Discussion

Histopathologic TIL grade was independently predictive for OS in this large national cohort. Significant differences in the likelihood of non-brisk or brisk TIL relative to absent grade were present with regards to LVI, ECS and immune status. TIL grade may be a useful prognostic factor to consider in addition to more granular characterization of TIL morphology and immunophenotype.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine malignancy with increasing incidence projected to exceed 3000 cases diagnosed in the United States in 2025 [Citation1]. The immune system including immune response is believed to play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of MCC [Citation2]. Integration of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) and damage from ultraviolet radiation have been associated with MCC development, with both MCPyV positive and negative tumors demonstrating immunogenicity [Citation3]. Recent advances in systemic therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic MCC treated with immunotherapy (IO) have been paradigm shifting with select patients demonstrating durable responses on IO [Citation4,Citation5]. Unfortunately not all patients with advanced MCC have clinically meaningful responses to IO (objective response rate of 56% with first-line IO for advanced MCC in the phase II trial by Nghiem et al. [Citation6]). Defining prognostic factors in addition to those used for AJCC staging may help identify patients at risk for suboptimal therapeutic outcomes.

Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) grade is a semi-quantitative histopathologic measure purported as a surrogate marker of the host immune response [Citation7] and has been associated with clinical outcomes including survival for multiple tumor types [Citation8–10]. The prognostic significance of TIL grade and survival for patients with MCC has not been completely elucidated with studies demonstrating conflicting results [Citation11–15]. Further characterization of TIL grade as an independent prognostic factor for patients with MCC and the relationship between TIL grade and known clinical prognostic factors including immune status, lymph node involvement and tumor size may help guide recommendations for clinical surveillance and better define which patients may benefit from novel therapeutic management. We performed an analysis of a large national database to determine if histopathologic TIL grade was independently associated with overall survival (OS) in patients with non-metastatic MCC and to characterize the relationship between TIL grade and other known clinical prognostic factors.

Material and methods

Adult patients diagnosed from 2010 to 2014 with non-metastatic, resected MCC with known details regarding TIL grade, adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy were abstracted from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) [Citation16] (Supplemental Figure 1). The NCDB, a joint project of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society, is a large national database which captures and maintains hospital-level data including therapeutic details of initial treatment course for ∼70% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States. TIL grade was abstracted from the dataset using collaborative stage site-specific factors coding for histopathologic examination of the tumor specimen (absent, non-brisk or brisk). TIL grade is a semi-quantitative factor recommended by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to be documented in histopathologic reports in addition to TNM staging [Citation17]. An absent TIL grade was defined by no lymphocyte-admixed tumor cells present in the specimen (even if lymphocytes were present in perivascular areas within the tumor or beyond the tumor border but not abutting tumor cells). A brisk TIL grade was defined by the presence of infiltrating lymphocytes along 90% of the circumference of the base of the lesion or a diffuse lymphocyte infiltrate present throughout the vertical growth phase of the lesion. Specimens with lymphocyte infiltrates not meeting the aforementioned criteria for brisk TIL grade were categorized with non-brisk TIL grade [Citation17]. Coders are instructed to abstract TIL grade from histopathology reports in the electronic medical record in accordance with the above.

Immune status was also abstracted from the dataset using collaborative stage site-specific factors coding for etiologies leading to profound immunosuppression (IS). Profound IS is coded in accordance with recommendations from the AJCC, and coders are instructed to review physician consult notes, patient histories and other available documents in the electronic medical record to determine if a patient is listed as being immunocompromised, immunosuppressed or having IS. In addition, these conditions must be active or have been diagnosed within 2 years of MCC diagnosis to code for profound IS [Citation18]. Eleven hundred and ninety-two (74.8%) patients in the cohort underwent surgical evaluation of lymph nodes with sentinel lymph node biopsy or lymph node dissection. Final surgical margin status after definitive surgical resection was abstracted from the dataset with patients listed with residual tumor NOS, microscopic residual tumor or macroscopic residual tumor categorized as having residual tumor after definitive surgical resection in the study cohort. Patients who received <30 Gy or >80 Gy of adjuvant radiation were excluded to limit potential inclusion of patients receiving atypical doses of adjuvant radiation. Patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy were also excluded from the study cohort.

Baseline patient and tumor factors were abstracted from the dataset and adjusted for in the performed multivariable analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize differences in the overall cohort stratified by TIL grade with regards to the aforementioned clinical factors. OS was defined as time from surgical resection to death from any cause or censoring. Kaplan–Meier’s methods and the log-rank test were used to compare OS for the cohort stratified by TIL grade. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model adjusting for a priori selected clinical factors including age, sex, TIL grade, immune status, pathologic tumor size, number of positive lymph nodes, extracapsular extension (ECS) and both adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy as time-varying covariates was considered to identify factors associated with OS. Time from surgery composed the underlying time axis in the performed analyses. Time-dependent multivariable Cox regression was used to limit immortal time bias [Citation19,Citation20] which may occur if early deaths prevent patients from receiving adjuvant therapy. As such, patients who received adjuvant radiation were included in the surgery group prior to initiation of radiotherapy, at which time they were considered in the adjuvant radiation group. The same process was used for patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy.

Schoenfeld residuals were considered to ensure the global test of proportional hazards was not violated. Multinomial logistic regression was performed to assess clinically relevant factors including number of positive lymph nodes, tumor size, immune status, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and ECE and likelihood of TIL grade (non-brisk and brisk TIL grade simultaneously compared with absent TIL grade (reference)). Multiple imputation was performed on the entire data set to account for missing data bias using a chained equations approach [Citation21]. The R packages mice and miceadds were used to perform multiple imputation and analysis of 10 generated data sets [Citation22,Citation23]. All tests were two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software v3.3.1 [Citation24]. Significance was defined as α ≤ 0.05. This study was designed in concordance with STROBE guidelines [Citation25], and approved by an institutional review board.

Results

Study cohort

The study cohort was comprised of 1594 patients with resected, non-metastatic MCC with known TIL grade (1175 patients with absent TIL, 300 patients with non-brisk TIL and 119 patients with brisk TIL grade, ). The median follow up for the cohort was 29.5 months (IQR: 17.0–46.5 months). Immune status was known for 1097 patients or 68.8% of the cohort (997 patients with known immunocompetence (IC) and 100 patients with IS). Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (32 patients) was the most common etiology of IS (25 patients with solid organ transplantation, 26 patients with HIV/AIDS/other and 17 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma).

Table 1. Baseline patient, tumor and treatment details.

Histopathologic TIL grade and OS

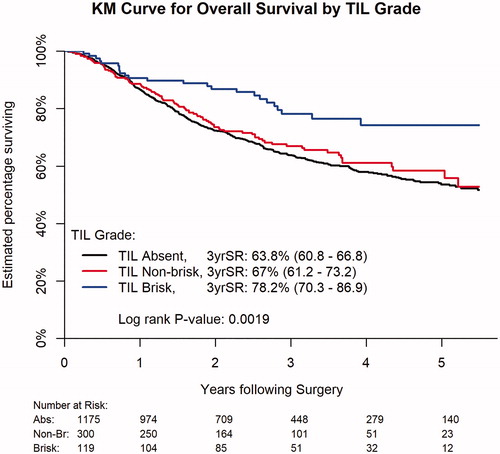

The 3-year OS rate was higher for patients with brisk TIL grade (78.2%) compared to patients with non-brisk TIL (67.0%) or absent TIL grade (63.8%, p=.0019, ). TIL grade was an independent predictor of OS (p=.0031) adjusting for clinical prognostic and treatment factors (age, sex, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score, immune status, adjuvant radiation, adjuvant chemotherapy, surgical margin, tumor size, LVI, number of positive lymph nodes, ECS, diagnosis year and tumor subsite, ). Both brisk (HR: 0.55, CI 0.36–0.83) and non-brisk (HR 0.77, CI 0.60–0.98) TIL grade were associated with adjusted decreased mortality hazards relative to absent TIL grade (reference).

Table 2. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model for predictors of overall survival.

Additional significant predictors of OS in the cohort included adjuvant chemotherapy, surgical margin status, immune status, age, sex, positive lymph node number, ECS and tumor size (all p values<.05, Supplemental Table 1). Immunosuppression (HR 2.29, CI 1.62–3.23) was associated with increased hazard of death relative to IC (reference). Extracapsular extension (HR: 2.00, CI 1.54–2.58) was associated with increased hazard of death (no ECS reference). Lymphovascular invasion (HR 1.15, CI 0.92–1.43) was not significantly associated with increased hazard of death (no LVI as reference, p value = .2229).

Relationships between TIL grade and other clinical factors

Multiple adverse prognostic factors were associated with increased likelihood of non-brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade in the cohort (). Patients with 1–3 positive lymph nodes (OR: 1.61, CI 1.15–2.26) were more likely to have non-brisk TIL grade (absent TIL grade as reference). Patients with LVSI (OR: 1.72, CI 1.27–2.33) and IS (OR 1.90, CI 1.12–3.22) were also more likely to have non-brisk TIL grade (absent TIL grade as reference). Patients with ECS (OR: 0.21, CI 0.07–0.59) were less likely to have brisk TIL grade (absent TIL grade as reference). Patients with LVSI (OR: 2.05, CI 1.31–3.21) were also more likely to have brisk TIL grade (absent TIL grade as reference). Tumor size, age, Charlson/Deyo comorbidity score and anatomic subsite were not associated with increased likelihood of non-brisk (relative to absent) or brisk (relative to absent) TIL grade.

Table 3. Multinomial, multivariable logistic regression model of clinical factors and likelihood of TIL grade.

Discussion

In this analysis of a national database of patients with non-metastatic MCC, histopathologic, TIL grade was associated with OS with significantly decreased adjusted hazard of death for patients with a brisk TIL grade relative to those with an absent TIL grade. Patients with adverse prognostic factors including 1–3 positive lymph nodes, IS and LVI were more likely to have non-brisk TIL grade relative to absent grade. Patients with LVI were more likely to have a brisk-TIL grade relative to absent grade. Patients with ECS were significantly less likely to have a brisk-TIL grade relative to absent grade. Tumor size, age and sex were not significantly associated with likelihood of TIL grade in our cohort.

The value of histopathologic TIL grade as an independent prognostic factor for patients with MCC has not been consistently demonstrated in prior studies. Andea et al. demonstrated TIL (categorized as absent vs. present with improved disease-specific survival for present TIL) was associated with disease-specific survival by univariable but not multivariable analysis in a retrospective analysis of 156 patients with MCC [Citation26]. Similarly, Paulson et al. found TIL grade (absent vs. present) to be significantly associated with MCC-specific survival by univariable but not multivariable analysis of 129 patients [Citation13]. Subsequently, characterization of the immunophenotype of the tumor infiltrate has been suggested as a more robust predictor of clinical outcomes in a number of studies with quantification of distinct cell types including CD8 + [Citation13,Citation14,Citation27], CD3 + [Citation11,Citation12] and FOXP3+ lymphocytes [Citation11,Citation14,Citation28]. However, histopathologic TIL grade was categorized as absent versus present in a number of prior studies [Citation13,Citation26] which in addition to smaller study cohorts relative to this current analysis may have limited ability to differentiate between non-brisk and brisk TIL grades with regards to clinical outcomes. In contrast, histopathologic TIL grade (categorized as absent, non-brisk and brisk) was significantly associated with OS adjusting for relevant clinical factors in our retrospective analysis of more than 1500 patients with MCC and known histopathologic TIL grade. We agree quantifying the morphology and immunophenotype of the tumor infiltrate provides a more nuanced understanding of the host immune response than histopathologic TIL grade alone and should be considered in any immunoscore model attempting to serve as a robust surrogate of the host immune response. Despite reduced granularity, our results suggest histopathologic TIL grade may be a useful clinical prognostic factor to consider in addition to the cellular composition of the tumor infiltrate.

The association between surrogate markers of the host immune response including histopathologic TIL grade and other relevant clinical factors in MCC is less described in comparison to cutaneous melanoma [Citation7,Citation29]. Walsh et al. showed brisk TIL density was associated with MCPyV positive tumors [Citation28] but did not investigate if TIL grade was associated with clinical factors such as lymph node positivity, tumor size or immune status. Ricci et al. performed an analysis of 95 patients with MCC and did not find either singly evaluated IHC TIL markers (CD3+, CD8+, FOXP3+, PD-L1+) or TIL immunoscore (scored 1–4 by number of positive IHC markers) to be significantly correlated with tumor size, advanced disease (stage III/IV), angioinvasion or tumor thickness [Citation14]. In this current analysis, multiple adverse clinical factors (1–3, positive lymph nodes and IS) were associated with increased likelihood of non-brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade. Similarly, Weiss et al. found non-brisk TIL grade to be associated with adverse clinical factors including thicker tumors, higher rates of ulceration and mitoses relative to brisk or absent TIL grade in an analysis of 1241 patients with primary melanoma, with the question raised of whether non-brisk TIL grade may be associated with a partially failed immune response [Citation7]. Further, gene expression profiling of a subset of tumors in their cohort demonstrated differential gene expression between brisk and non-brisk TIL groups with brisk TIL tumors showing gene expression patterns involving pathways enriched for the activation, development and migration of T lymphocytes. The results of this current study support distinguishing between absent, non-brisk and brisk TIL states in future studies of patients with MCC in lieu of considering TIL as absent versus present.

Extracapsular extension (associated with a greater than twofold increase in adjusted hazard of death) was associated with reduced likelihood of brisk TIL grade (relative to absent TIL grade). Of note, patients with LVI were more likely to have brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade. Of similar interest, despite association with multiple adverse prognostic factors, non-brisk TIL grade was associated with decreased adjusted hazard of death relative to absent TIL grade in our study. These findings may in part be attributable to heterogeneity present within subgroups categorized by histopathologic TIL grade with regards to the immunophenotype of the infiltrate. Subsequently, we caution prognostication using histopathologic TIL grade alone for patients with MCC without contextualization of the morphology and immunophenotype of the tumor infiltrate and consideration of other relevant clinical factors.

Limitations

There are limitations present in this study in addition to those inherent to retrospective analysis which merit further discussion. TIL grade was not available for most patients in the overall (pre-selection criteria) dataset (Supplemental Table 1), potentially limiting generalizability of the study results to the overall population of patients with MCC in the US. The composition of the tumor infiltrate varies with regards to density and topographic distribution of cell types for MCC with distinct cell types purported to have immunostimulatory versus immunoregulatory effects [Citation28]. Data regarding the cellular composition of tumor infiltrates using immunohistochemical staining was not available in the dataset. Subsequently, we were unable to characterize the cellular composition of tumor infiltrates in our cohort or determine the association between individual cell types within the infiltrate and OS. We were unable to adjust for inter-reviewer variability in TIL grade scoring potentially present in the dataset, though high rates of interobserver agreement regarding TIL grade have previously been reported [Citation13]. Merkel cell polyomavirus positivity was unavailable in the dataset and could not be adjusted for in the performed analyses. Though we abstracted available immune status from the dataset, we were unable to characterize the severity of IS by quantification of circulating lymphocyte populations. The NCDB collects treatment details regarding the initial course of therapy and we were unable to adjust for salvage therapies potentially modulating OS. Cancer-specific clinical outcomes of interest including MCC-specific-survival, progression free survival and locoregional control are unavailable in the dataset and could not be examined.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, we performed one of the largest analyses to date of patients with non-metastatic MCC with known histopathologic TIL grade. TIL grade was an independent predictor of OS with significantly decreased risk of death for patients with brisk TIL grade with respect to those with an absent TIL grade. Multiple adverse clinical prognostic factors including IS were associated with increased likelihood of non-brisk TIL relative to absent TIL grade, supporting differentiating non-brisk TIL grade from brisk TIL grade rather than considering TIL grade as absent versus present. These findings are hypothesis generating and we caution using histopathologic TIL grade alone to prognosticate OS for patients with MCC without consideration of TIL cellular composition.

Further studies with large cohorts of MCC patients with granular details regarding TIL morphology and immunophenotype are needed to validate and better define the relationships between surrogate markers of the host immune response and other relevant clinical and histopathologic prognostic factors. These studies are also necessary to determine if an immunoscore incorporating histopathologic TIL grade along with IHC markers of the TIL immunophenotype may serve as a more robust surrogate of the host immune response than a immunoscore model without consideration of TIL grade. Such a robust surrogate for the host immune response would be of high clinical value in both optimizing treatment selection and surveillance for high-risk patients with MCC.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (32.9 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Power Point (34.4 KB)Acknowledgments

The data used in the study are derived from a de-identified NCDB file. The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):457–463.e2.

- Harms PW, Harms KL, Moore PS, et al. The biology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: current understanding and research priorities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(12):763–776.

- Becker JC, Stang A, DeCaprio JA, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17077.

- Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1374–1385.

- Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2542–2552.

- Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al. Durable tumor regression and overall survival in patients with advanced Merkel cell carcinoma receiving pembrolizumab as first-line therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(9):693–702.

- Weiss SA, Han SW, Lui K, et al. Immunologic heterogeneity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte composition in primary melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;57:116–125.

- Thomas NE, Busam KJ, From L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade in primary melanomas is independently associated with melanoma-specific survival in the population-based genes, environment and melanoma study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4252–4259.

- Leon-Ferre RA, Polley MY, Liu H, et al. Impact of histopathology, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and adjuvant chemotherapy on prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;167(1):89–99.

- Huh JW, Lee JH, Kim HR. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with colorectal cancer. Arch Surg. 2012;147(4):366–372.

- Sihto H, Böhling T, Kavola H, et al. Tumor infiltrating immune cells and outcome of Merkel cell carcinoma: a population-based study. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(10):2872–2881.

- Feldmeyer L, Hudgens CW, Ray-Lyons G, et al. Density, distribution, and composition of immune infiltrates correlate with survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(22):5553–5563.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Tegeder AR, et al. Transcriptome-wide studies of Merkel cell carcinoma and validation of intratumoral CD8+ lymphocyte invasion as an independent predictor of survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1539–1546.

- Ricci C, Righi A, Ambrosi F, et al. Prognostic impact of MCPyV and TIL subtyping in Merkel cell carcinoma: evidence from a Large European Cohort of 95 patients. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31(1):21–32.

- Behr DS, Peitsch WK, Hametner C, et al. Prognostic value of immune cell infiltration, tertiary lymphoid structures and PD-L1 expression in Merkel cell carcinomas. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(11):7610–7621.

- Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, et al. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683–690.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2019;72(5):337–340.

- Jennifer Ruhl EW, Hofferkamp J. Site-Specific Data Item (SSDI) manual. Illinois: NAACCR, Springfield; 2019.

- Agarwal P, Moshier E, Ru M, et al. Immortal time bias in observational studies of time-to-event outcomes: assessing effects of postmastectomy radiation therapy using the National Cancer Database. Cancer Control. 2018;25(1):1073274818789355.

- Park HS, Gross CP, Makarov DV, et al. Immortal time bias: a frequently unrecognized threat to validity in the evaluation of postoperative radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(5):1365–1373.

- Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Katalinic A. Imputation of missing values of tumour stage in population-based cancer registration. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:129.

- van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:67.

- Robitzsch AG. miceadds: some additional multiple imputation functions, especially for 'mice'. Kiel, Germany: R package version 3.9-14. 2020.

- Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499.

- Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer. 2008;113(9):2549–2558.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Simonson WT, et al. CD8+ lymphocyte intratumoral infiltration as a stage-independent predictor of Merkel cell carcinoma survival: a population-based study. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142(4):452–458.

- Walsh NM, Fleming KE, Hanly JG, et al. A morphological and immunophenotypic map of the immune response in Merkel cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;52:190–196.

- Azimi F, Scolyer RA, Rumcheva P, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte grade is an independent predictor of sentinel lymph node status and survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2678–2683.