Abstract

Introduction

Resuming work during or after cancer treatment has become an important target in cancer rehabilitation.

Purpose

The aim was in a controlled trial to study the return to work (RTW) effect of an early, individually tailored vocational rehabilitation intervention targeted to improve readiness for RTW in cancer survivors.

Material and methods

Participants diagnosed with breast, cervix, ovary, testicular, colon-rectal, and head-and-neck cancers as well as being employed were allocated to a vocational rehabilitation intervention provided by municipal social workers (n = 83) or to usual municipal RTW management (n = 264). The intervention contained three elements: motivational communication inspired by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy by which RTW barriers were addressed, municipal cancer rehabilitation and finally employer and workplace contact. RTW effect was assessed as relative cumulative incidence proportions (RCIP) in the control and intervention group within 52 weeks of follow-up, estimated from the week where treatment ended at the hospital. RCIP was interpreted and reported as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) adjusted for gender, age cancer diagnosis, education, comorbidity, and sick leave weeks.

Results

Across cancer diagnoses 69 (83.1%) and 215 (81.4%) returned to work in the intervention and control group, respectively. No statistical effect was seen (RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.98–1.19)). Repeating the analyses solely for participants with breast cancer (n = 290) showed a significant effect of the intervention (RR 1.12 (95% CI 1.01–1.23)).

Conclusion

More than 80% returned to work in both groups. However, no statistical difference in RTW effect was seen across cancer diagnoses within one year from being exposed to an early, individually tailored vocational rehabilitation intervention compared with usual municipal RTW management.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN50753764

Introduction

Cancer survival is increasing worldwide. Approximately 40% of patients diagnosed with cancers are of working age [Citation1], for breast cancer alone the incidence is approximately 50% [Citation2]. Therefore, resuming work during or after cancer treatment has become an important target in cancer rehabilitation. Cancer survivors are highly motivated to resume work, as work constitute normal life, can increase quality of life and economic independence [Citation3,Citation4]. However, the cancer disease itself, treatment and late effects increase the risk of early withdrawal from the labor market [Citation5,Citation6]. Job loss is experienced by up to 53% of cancer survivors [Citation7], and unemployment reportedly 1.4 times more likely in cancer survivors than among people without cancer [Citation8]. Several return to work (RTW) interventions have been studied in the pursuit of how cancer survivors are best supported in their RTW attempts [Citation8,Citation9]. The most recent Cochrane review [Citation8] concluded, that multidisciplinary interventions where physical, mental and vocational aspects of survivorship were targeted simultaneous, produced superior though modest effects on RTW compared with usual care and one-dimensional interventions. A recent cluster-randomized multicenter trial found no RTW effect after an inpatient vocational intervention [Citation10].

The Cancer and Work model [Citation11] was used as framework in the development of the present RTW intervention [Citation12]. Cancer survivors’ perceived lack of support at workplace level; i.e., poor communication, non-adjustable work environment requested due to reduced work ability, and discrimination, have been shown to hinder RTW [Citation13]. Thus, employer support in vocational rehabilitation may help cancer survivors to overcome the imbalance between work ability and work demands. Therefore, the involvement of the cancer survivors’ employer was a focal point in the present intervention. A previous pilot study involved the employer but it was inconclusive whether this element improved RTW [Citation14]. Recent study protocols describing RTW interventions in multiple cancer types; two did not include employers in the intervention [Citation15,Citation16] and one did [Citation17].

Additionally, vocational rehabilitation efforts are commonly initiated after cancer treatment; in the meantime cancer survivors are often left on their own to deal with work-related issues [Citation18,Citation19]. This may constitute a challenge with regard to social security legislation; e.g., in Denmark it leaves limited time for the RTW preparation, employer involvement and work place adjustments, as the sick leave benefit period ends or is to be renegotiated with possible extension after 22 weeks of sick leave [Citation20]. Therefore, the timing of a RTW intervention may be another crucial element.

The objective was in a controlled trial to study the return to work (RTW) effect of an early, individually tailored vocational rehabilitation intervention targeted to improve readiness for RTW in cancer survivors.

Material and methods

The methods of the present trial have been thoroughly described in a study protocol [Citation12].

Design

The study design was a controlled trial conducted at the Department of Oncology at Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark with a 12 months follow-up.

Study population

The source population was residents in Central Denmark Region, treated for their breast, colon-rectal, head and neck, thyroid gland, testicular, ovarian or cervix cancer, at Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital.

Participants eligible for the intervention were patients referred to curative intended radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, resided in the municipalities of Silkeborg or Randers (two of 19 municipalities in the region), between 18 and 60 years of age, and at inclusion permanently or temporary employed (with at least 6 months left on their contract). Participants were excluded, if the treating physician considered participation unethical, or if the participant could not read or speak Danish.

The control group had identical inclusion and exclusion criteria except for the municipality of residence. The control group was identified via electronic patient records at Aarhus University Hospital. To ensure comparable inclusion dates in the intervention and control groups, inclusion was defined as the date of first treatment with either chemo- or radiotherapy.

Recruitment process

Recruitment of the intervention group took place at either the oncological department or the municipal department for social services (in the following referred to as a job center (JC)), responsible for the RTW intervention.

Health care staff assigned to the trial identified eligible participants and notified the treating oncologist, who briefly informed the patient about the project, handed out written information along with a consent formula allowing a social worker (SW) contacting the patient for further information and final consent for participation. The two municipal SWs responsible for delivering the intervention were also able to identify eligible sick-listed participants who were entitled to receive sickness benefit.

According to the Danish Sickness Benefit Act [Citation20] entitlement to sickness benefit require employment (self-, full- or part-time) in at least 74 h within an eight week period. Employers are responsible for paying wage during the first four weeks of a sick leave spell. If spells exceed four weeks, employers are reimbursed by the state equivalent to the amount of sickness benefit. By law sick leave spells exceeding eight weeks require the beneficiary to participate in follow-up meetings at the municipal JC, where a RTW plan is initiated. Sickness benefit is allowed for a maximum period of 22 weeks, by then the JC decides whether justified reasons for prolongation exist, the beneficiary is entitled to other social benefits, or RTW is possible. Thus, eligible study participants were invited to participate at obligatory follow-up meetings at the JC. Finally, if participation was agreed upon, i.e., to also involve next of kin, employer and colleagues in the RTW intervention, a first meeting with the SW was planned at which the written consent formula was signed.

Inclusion took place from December 2013 to April 2017, where the ad priori sample size of 90 breast cancer patients in the intervention group was reached [Citation12].

Intervention

Control group

The participants were assumed to receive the usual municipal sickness benefit management including obligatory follow-up meetings and initiation of a RTW plan. However, cancer patients are often exempt from attending these meetings justified by the severity of the disease.

Intervention group

Before inclusion started the SWs attended a four-day course in the use of elements from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [Citation21,Citation22] led by an experienced psychologist. The acquired communication skills enabled the SWs to confront and help the participants to clarify their personal values and immediate needs, and through psychological fusion enhance their commitment to and change of behavior toward RTW [Citation12]. To comply with the intervention protocol; the SWs received supervision once every month by the aforementioned psychologist throughout the study period.

At the first meeting with the SW a questionnaire on readiness for RTW was answered. A supplementary need assessment was carried out, including questions about the current health status related to the cancer diagnosis, type of employment and job tasks, relationship with employer and colleagues, and to what extent disclosure of cancer diagnosis had taken place at the workplace. Finally, whether agreements with the employer were made about sick leave duration, reduced work hours and/or modified job tasks. The individual need assessment outlined promoting and inhibiting RTW elements, thereby informed the SW and cancer survivor about intervention targets, and an initial RTW plan was tailored with the participant.

The participants were not exempted from the obligatory follow-up meetings, but number and frequency of meetings were individualized according to the need assessment.

To coordinate the RTW plan with the participant’s employer already from the onset of the intervention, the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) served as inspiration for the RTW goal setting with the employer [Citation12,Citation23,Citation24]. The SWs encouraged place-and-train activities at the workplace to address barriers and find solutions that balanced both the employer’s and employee’s needs. The SWs also provided information to the employer about reimbursement schemes that allowed hiring temporary workers whilst sick-listed employee recovered.

Finally, the participants’ rehabilitation needs other than vocational were assessed by the ACT-inspired communication and questionnaire-based answers. These needs could be met by provision of other intervention elements, e.g., municipal cancer rehabilitation, general practitioner consultations, and attendance in activities within the Danish Cancer Society.

Follow-up questionnaires were repeated for the readiness for RTW after 3 and 12 months.

The intervention was continued until the participants returned to work or for 1 year.

Outcomes

We expected the intervention to improve readiness for RTW [Citation12]. Readiness for RTW was evaluated by the Danish version of the readiness for RTW (RRTW-DK) [Citation25]. RRTW-DK is a 22-item questionnaire with four underlying stages for persons not working, and two stages for persons currently working. Items are scored on a five-point ordinal scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), mean scores are calculated for each stage.

In the analysis the participants were allocated to the stage with the highest mean score [Citation26]. Changes in readiness between 3 and 12 months’ follow-up were categorized: no changes, declined, or increased. As few (n = 4) declined; this category was collapsed with those who did not change

Primary outcome

RTW within 1 year was defined as four consecutive weeks of absence of social benefits, except part-time sickness benefit or benefit related to modified jobs. RTW was identified in the Danish Register for EvAluation of Marginalization (DREAM), which contains weekly information on all tax-financed social benefits payed to Danish residents from 1991. DREAM provides valid data on various labor market outcomes [Citation27,Citation28].

Number of weeks were counted from the week where treatment ended at the hospital until RTW, competing risks (age-related pension, disability pension or death), censoring (emigration) or end of the 1-year follow-up period, whatever occurred first.

Secondary outcomes whether the effect was modified by comorbidity and education

Comorbidity was based on Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (CCI) [Citation29]. Data on diagnoses 5 years prior to the date of the cancer diagnosis were used to generate CCI [Citation30]. Nineteen predefined somatic comorbidities were identified in the National Patient Registry in Denmark [Citation31] and scored on a 3-point severity scale and summarized. CCI was dichotomized: zero or one or more comorbidities.

Highest educational attainment in the year of inclusion was identified in Statistics Denmark [Citation32]. Educational attainment was categorized as: low (primary education; lower secondary education; vocational training), medium (upper secondary education; short-cycle higher education) or high (medium- and long-cycle higher education; research training). In the analyses medium and high were collapsed into one category.

Baseline characteristics

Treatment encompassed: breast (operation + chemo/radiation/endocrine therapy), cervix (radiation + operation/chemo), ovary (operation + chemo), testicular (operation + chemo), colon-rectal (operation + chemo), and head- and-neck (radiation + operation). Treatment types were collapsed into two categories: two-four incl. chemo or one-three excl. chemo treatment modalities.

Disposable income the year prior to the year of inclusion was identified in Statistics Denmark, defined as the personal income after tax plus interests from rental value of own home. The variable was converted from Danish kroner to US Dollars based on a mean exchange rate from 2014 to 2017 [Citation33].

The participants’ occupation the year prior to inclusion was identified in Statistics Denmark and categorized: (1) Administration, teaching or healthcare, (2) Culture entertainment or service, (3) Vocational service, Trading and transport, (4) Mining and quarrying and (5) Other (Finance and insurance, Information and communication, Work and supply service, Real estate and rental, Agriculture, forestry and fishing).

Total number of sick leave weeks in the second year prior to inclusion date, where identified in DREAM.

Work status at the inclusion date was identified in DREAM and was dichotomized: working/receiving no social security benefits, or receiving any kind of social security benefit indicative of work disability.

Potential confounders

Age was defined at the time of inclusion. Age and gender were derived from the unique 10-digit personal identification number assigned to every Danish resident.

Cancer diagnosis was retrieved from the hospital registry and categorized: breast-, cervix-, ovary-, testicular-, colon-rectal-, and head-neck cancer. In analyses the variable was dichotomized in breast and other cancers.

The total number of sick leave weeks the first year prior to the inclusion date, were identified in DREAM and was treated as a continues variable in the analyses.

Statistics

The unique 10-digit personal identification number enabled data linkage on an individual level between the hospital records, the municipal records, the questionnaire-based data, and the registry data.

Baseline characteristics were stratified on non-participants (eligible patients but not informed about the project or declined participation), intervention, and control group. Differences in characteristics between the control and intervention groups were tested by chi2, Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon rank sum test.

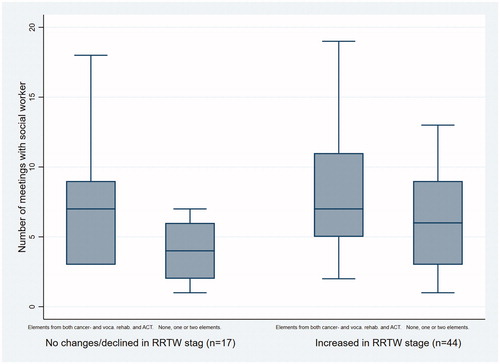

The number of meetings with the SW was summarized. This number was illustrated in relation to changes in readiness for RTW combined with which types of intervention elements the participants had received: elements from both cancer- and vocational rehabilitation plus ACT, one of two elements or none.

Effect was assessed as relative differences between cumulative incidence proportions (CIP) of RTW in the control and intervention group. We expected to be able to retrieve the exact dates of treatment end. However, the European Data Protection Regulations changed during the study period and prohibited us from getting access to these individual dates. Instead average treatment durations, based on standard treatment courses, for each included diagnosis were added to the inclusion date to define entry date. For breast (107 days), colon-rectal (91 days), cervix (91 days), ovary (no available treatment duration – inclusion date was used instead), testicular (61 days), and head-neck cancer (76 days).

Because of competing risks and censoring; effect was analyzed with the use of the pseudo values method [Citation34,Citation35]. Measure of association was relative CIP (relative ‘risk’ (RR) of RTW) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Four generalized linear regression models were performed: a crude, one that adjusted for the potential confounders, and finally models that introduced interactional terms by education and CCI, respectively. All analyses were repeated for participants with breast cancer solely. Statistical significance level was p < 0.05. Analyses were carried out in STATA version 16.

Results

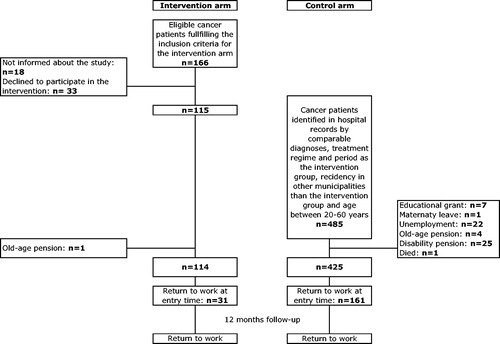

A total of 166 participants met the inclusion criteria for the intervention group, of whom 18 were not invited (health care staff overlooked these patients) and 33 declined participation (reason was not given). After completing the inclusion for the intervention group, the control group was identified through the hospital records and comprised 485 cancer patients with identical inclusion criteria except municipality of residence. Unemployed participants in the intervention (n = 1) and control group (n = 60) were excluded. This left 114 and 425 patients in the trial; of whom 31 (27.2%) and 161 (37.9%) had already returned to work before finalizing cancer treatment and were not at “risk” of experiencing RTW, leaving 347 participants ().

Characteristics

At inclusion the intervention and control groups were comparable with regards to most characteristics. However, significantly fewer had breast cancer and more had long-term sick leave the year prior to inclusion in the intervention group than in the control group ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the non-participants (n = 50), intervention group (n = 83) and control group (n = 264).

Compliance with study protocol

Employers were involved in 70.3% of the 83 cases in the intervention group (results not shown). Sixty-one (73.49%) answered the RRTW-DK; from 12 to 12 months’ follow-up 13 remained in the same stage, four declined, and 44 increased. The average number of meetings with the SW was highest among those who increased in readiness for RTW stage and received elements from both cancer- and vocational rehabilitation plus ACT (n = 26, mean 8.31 (SD 4.4)) and among those who increased in stage but received none, one or two elements (n = 18, mean 6.06 (SD 3.5)). The equivalent numbers for those who remained or declined in readiness for RTW stage were (n = 7, mean 7.43(SD 5.2)) and (n = 10, mean 3.90 (SD 2.1)), respectively ().

Effect analyses

In the intervention group; the total observation time was 2318 weeks until RTW (n = 69 (83.1%)), competing events (n = 3) or follow-up ended (n = 11). In the control group; the equivalent figures were 6508 weeks until RTW (n = 215 (81.4%)), competing events (n = 4) or follow-up ended (n = 45).

A small insignificant effect was found in the intervention versus the control group (RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.98–1.19)). No significant interactional effects were found for CCI (p = 0.70) or education (p = 0.99, ). Repeating the analyses solely for participants with breast cancer showed a significant effect of the intervention (RR 1.12 (95% CI 1.01–1.23). Neither CCI (p = 0.87) nor education (0.34) modified the effect of the intervention ().

Table 2. Effect on Return to work of vocational rehabilitation in cancer survivors allocated to intervention (n = 83) or control group (n = 264).

Table 3. Effect on Return to work of vocational rehabilitation in breast cancer survivors allocated to intervention (n = 65) or control group (n = 225).

Discussion

Main findings

More than 80% returned to work in both groups. However, the vocational rehabilitation intervention did not increase the RTW chance compared with usual municipal RTW management across cancer diagnoses. A significant 12% increased likelihood of RTW was however, found among breast cancer survivors alone. Neither comorbidity nor educational attainment modified the effect of the intervention on likelihood of RTW.

Interpretation of results

The most recent Cochrane review on RTW interventions for cancer patients requested vocational interventions [Citation8] as these are a scarcity [Citation15,Citation16]. The involvement of the employer was thus a focal point in the present intervention to accommodate work-related adjustments, and compliance with this ideal was high. As was the use of ACT, supposed to increase the participants’ readiness for RTW [Citation36]. Despite limitations with evaluative properties of the RRTW-DK [Citation25]; only 9% declined in readiness stage between 3 and 12 months follow-up and this was not due to non-compliant SW behavior. Thus, the small insignificant effect across cancer diagnoses and significant effect in breast cancer survivors was not ascribable to poor study protocol compliance. However, qualitative data from some of the employers involved in the present study indicated that they felt unsupported during the intervention [Citation37], which future intervention studies should address. The effect on RTW among the breast cancer women is interesting. These women may be more inclined to and feel comfortable with this particular intervention than men in general. The close relationship with the SW may have fueled the RTW goal setting and the involvement of the employer may also have supported them in facing work demands at the workplace and helped them to work accommodations [Citation13].

Another important element was the early onset of the intervention. As the RTW rates were high and almost similar in both study groups, we suspect that the timing of the intervention was not as innovative as we hypothesized. However, the control group’s ‘RTW management as usual’ constituted a black box as the content was unknown. It is a well-described phenomenon in rehabilitation effect studies that a possible non-existing standard care group precludes decisions on adjunctive effects [Citation38].

Cancer survivors with no or low level education, as a proxy for low socioeconomic status [Citation39], may experience the RTW-process more difficult than survivors with high level education; as unfavorable work conditions characteristic for low income and unskilled jobs may explain some of this inequality [Citation40]. The interactional effect of education did not support this hypothesis. Also, non-significant effects from comorbidity were seen. The majority of the recruited participants were breast cancer patients who for the most part have few comorbidities when diagnosed, but for some evolves over time to cancer-related late effects and an increased risk of developing post treatment comorbidity [Citation41]. Survivorship is thus not living without health complaints but rather facing a life with comorbidity and late effects from cancer treatment [Citation42]. Future studies need to investigate these implications on work participation [Citation43].

Limitations

The sample size calculations were based on an anticipated bigger difference in RTW rates between the intervention and control group [Citation12] than was found in the present study. Therefore, Type II error may have caused underestimated results. The prohibition of having access to the exact dates of treatment finalization may have caused non-differentiated misclassification, which may have added to the risk of underestimated effect results. Randomization was decided against due to the risk of intervention contamination within municipalities [Citation44], and residual confounding might have impacted the results, due to overall different RTW rates in the intervention and control municipalities.

As no participants were lost during follow-up, selection problems were only affecting external validity. Generalization should be done with caution to cancer patients other than women with breast cancer, to patients with low level education and to patients who manage to work when cancer treatment starts.

Implications

We hypothesized that the timing of the intervention allowed for a better tailored RTW plan than a management without the municipal obligatory follow-up meetings, by which RTW decisions may be made solely by the municipal JC – a decision that may impose considerable stress on the cancer survivor in balancing job demands and health status. This hypothesis should be investigated in future studies addressing whether RTW is more sustainable among cancer survivors receiving an early vocational rehabilitation intervention. The recruitment may as well be postponed to after initial RTW, as the survivors’ perceived work ability is reflected better in relation to actual work demands than during cancer treatment.

Conclusion

Usual municipal RTW management in a tax-financed social security setting proved to be equally effective in facilitating RTW compared with tailored vocational rehabilitation when analyzed across various cancer diagnoses. Due to limited statistical power the modifying effect of education and comorbidity was inconclusive. Post-hoc analyses showed however, that women in the intervention group with breast cancer had a significantly increased likelihood of RTW within 1 year after ending treatment.

Acknowledgment

We thank the SWs in the municipalities of Randers and Silkeborg for their outstanding effort and commitment throughout the study. We thank the staff at the Department of Oncology at Aarhus University Hospital for assisting in the identification of eligible cancer patients. In particular we thank, Professor Morten Hoyer, for facilitating the processes from study idea to actual inclusion and for always being constructive in every aspect of the involvement of the Department of Oncology at Aarhus University. We also want to appreciate psychologist, Joanna Wieclaw, for supervising the job consultants. Last but not least we owe great gratitude to the cancer patients for acceptance of participation in this study.

Disclosure statement

The funding bodies played no role in the design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119 Suppl 11(11):2151–2159.

- Nilsson MI, Petersson LM, Wennman-Larsen A, et al. Adjustment and social support at work early after breast cancer surgery and its associations with sickness absence. Psychooncology. 2013;22(12):2755–2762.

- Kennedy F, Haslam C, Munir F, et al. Returning to work following cancer: a qualitative exploratory study into the experience of returning to work following cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16(1):17–25.

- Peteet JR. Cancer and the meaning of work. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22(3):200–205.

- de Boer AG, Taskila T, Ojajarvi A, et al. Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301(7):753–762.

- Pedersen P, Aagesen M, Tang LH, et al. Risk of being granted disability pension among incident cancer patients before and after a structural pension reform: a Danish population-based, matched cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2020;46(4):382–391.

- van Egmond MP, Duijts SF, Jonker MA, et al. Effectiveness of a tailored return to work program for cancer survivors with job loss: results of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(9–10):1210–1219.

- de Boer AG, Taskila TK, Tamminga SJ, et al. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD007569.

- Lamore K, Dubois T, Rothe U, et al. Return to work interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review and a methodological critique. IJERPH. 2019;16(8):1343.

- Fauser D, Wienert J, Beinert T, et al. Work-related medical rehabilitation in patients with cancer-postrehabilitation results from a cluster-randomized multicenter trial. Cancer. 2019;125(15):2666–2674.

- Feuerstein M, Todd BL, Moskowitz MC, et al. Work in cancer survivors: a model for practice and research. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(4):415–437.

- Stapelfeldt CM, Labriola M, Jensen AB, et al. Municipal return to work management in cancer survivors undergoing cancer treatment: a protocol on a controlled intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:720.

- van Muijen P, Weevers NLEC, Snels IAK, et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2013;22(2):144–160.

- Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bos-Ransdorp B, Uitterhoeve LL, et al. Enhanced provider communication and patient education regarding return to work in cancer survivors following curative treatment: a pilot study. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):647–657.

- Tamminga SJ, Hoving JL, Frings-Dresen MH, et al. Cancer@Work - a nurse-led, stepped-care, e-health intervention to enhance the return to work of patients with cancer: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):453.

- Vidor C, Leroyer A, Christophe V, et al. Decrease social inequalities return-to-work: development and design of a randomised controlled trial among women with breast cancer. Bmc Cancer. 2014;14:267.

- Greidanus MA, de Boer A, de Rijk AE, et al. The MiLES intervention targeting employers to promote successful return to work of employees with cancer: design of a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):363.

- Taskila T, Lindbohm ML, Martikainen R, et al. Cancer survivors’ received and needed social support from their work place and the occupational health services. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(5):427–435.

- Tiedtke C, de RA, Dierckx de CB, et al. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):677–683.

- The Danish Ministry of Employment. The Danish Sickness Benefit Act. 2014.

- Dahl J, Wilson KG, Nilsson A. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the treatment of persons at risk for long-term disability resulting from stress and pain symptoms: A preliminary randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2004;35(4):785–801.

- Kahl KG, Winter L, Schweiger U. The third wave of cognitive behavioural therapies: what is new and what is effective? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;35(4):785–801.

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(4):280–290.

- Jordán de Urríes FDB. Supported employment. 2010;1–10. Available from: http://cirrie.buffalo.edu

- Stapelfeldt CM, Momsen AH, Lund T, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of the Danish version of the readiness for return to work instrument. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(2):325–335.

- Franche R-L, Corbiere M, Lee H, et al. The Readiness for Return-To-Work (RRTW) scale: development and validation of a self-report staging scale in lost-time claimants with musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(3):450–472.

- Stapelfeldt CM, Jensen C, Andersen NT, et al. Validation of sick leave measures: self-reported sick leave and sickness benefit data from a Danish national register compared to multiple workplace-registered sick leave spells in a Danish municipality. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):661–671.

- Biering K, Hjollund NH, Lund T. Methods in measuring return to work: a comparison of measures of return to work following treatment of coronary heart disease. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(3):400–405.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:83–2288.

- The Danish Health and Medicines Authority. The National Patient Registry. 2019. Available from: https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/da/registre-og-services/om-de-nationale-sundhedsregistre/sygedomme-laegemidler-og-behandlinger/landspatientregisteret

- Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):91–94.

- Yearly exchange rates by currency, type and methodology. [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://nationalbanken.statistikbank.dk/nbf/100250.

- Klein JP, Logan B, Harhoff M, et al. Analyzing survival curves at a fixed point in time. Stat Med. 2007;26(24):4505–4519.

- Parner ET, Andersen PK. Regression analysis of censored data using pseudo-observations. Stata J. 2010;10(3):408–422.

- Stergiou-Kita M, Pritlove C, Holness DL, et al. Am I ready to return to work? Assisting cancer survivors to determine work readiness. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):699–710.

- Petersen KS, Momsen AH, Stapelfeldt CM, et al. Reintegrating employees undergoing cancer treatment into the workplace: a qualitative study of employer and co-worker perspectives. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):764–772.

- Negrini S. Evidence in rehabilitation medicine: between facts and prejudices. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(2):88–96.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

- Amir Z, Brocky J. Cancer survivorship and employment: epidemiology. Occup Med (Lond). 2009;59(6):373–377.

- Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, et al. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5814–5830.

- Pryce J, Munir F, Haslam C. Cancer survivorship and work: symptoms, supervisor response, co-worker disclosure and work adjustment. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(1):83–92.

- Stapelfeldt CM, Klaver KM, Rosbjerg RS, et al. A systematic review of interventions to retain chronically ill occupationally active employees in work: can findings be transferred to cancer survivors? Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):548–565.

- Poulsen OM, Aust B, Bjorner JB, et al. Effect of the Danish return-to-work program on long-term sickness absence: results from a randomized controlled trial in three municipalities. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(1):47–56.