Abstract

Introduction

A large proportion of stage I cancers are found incidentally, which appears to be a prognostic factor. We investigated stage I lung cancers according to whether, or not, there had been clinical suspicion of lung cancer prior to referral and to see, if we could detect any difference regarding patient characteristics, work-up and mortality for incidental vs non-incidental findings as well as for asymptomatic vs symptomatic patients.

Methods

Medical records and referral documents for 177 patients diagnosed with stage I lung cancer were reviewed and divided based on whether the initial CT scan leading to diagnosis had been made due to suspicion of lung cancer or not. Patient characteristics and mortality between groups were compared, as well as mortality between patients with and without symptoms at the time of diagnosis.

Results

One-hundred-and-eight patients were diagnosed incidentally, while 69 patients were non-incidental findings. Among the incidental findings, 55% had no symptoms, whereas none in the non-incidental group were asymptomatic. Personal characteristics were comparable between the groups. Significantly more patients in the incidental group had malignant comorbidity. Non-malignant chronic co-morbidity was more prevalent in the non-incidental group, in particular lung disease. There was no difference in tumour size, histology, or survival for incidental vs non-incidental or for asymptomatic vs symptomatic patients.

Conclusion

A large proportion of stage I lung cancers are found incidentally, especially in patients with malignant co-morbidity. We found no difference in survival to indicate that we did or should handle these patient groups differently.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the predominant cause of cancer mortality in the developed world [Citation1]. One of the most important prognostic factors for lung cancer is the stage at the time of diagnosis. But only about 20% are found at the earliest stages (Ia/Ib) with the best prognosis [Citation2]. This is in part because most symptoms of lung cancer are common and non-specific, and the early stages may be symptomless [Citation3]. The non-specific symptoms may be interpreted as caused by other diseases, which may lead to a referral under suspicion of another disease than lung cancer. Lung cancer may then subsequently be discovered during the clinical investigations for the other disease. Previous studies have shown that a large proportion of stage I lung cancers apparently are found incidentally (up to 50%) while patients are investigated for other diseases than lung cancer [Citation4–6]. An incidental discovery of lung cancer is, in itself a favourable prognostic factor, probably mainly because of the higher prevalence of early-stage lung cancer among these patients. But even among these patients with a better than average prognosis, having symptoms appears to be a disadvantage for survival, even for patients with pathological stage I cancer [Citation7].

However, in the majority of these studies, an incidental finding is defined as the absence of symptoms at the time of diagnosis, rather than in relation to the circumstances leading up to the referral for cancer work-up. We theorised that patients with symptoms very early in their course could have a more aggressive cancer and might benefit from an intensified work-up leading to earlier treatment. To further evaluate this hypothesis, and thus to ensure that we would handle the diagnostic work-up of the individual patients in the most appropriate way, we sought to determine how large a portion of our early-stage lung cancer patients were truly without symptoms possibly related to their lung cancer, prior to the referral to our department. It might be that they had symptoms, which just had not led to the suspicion of lung cancer, but still had resulted in a referral on the suspicion of another disease. We further wanted to see whether the patients differed with respect to personal characteristics, in tumour size and histology. Also, we wanted to see whether the diagnostic work-up had been different, when there was no initial clinical suspicion of lung cancer compared to when the patients had symptoms, and in the end, whether it had an impact on their survival.

So, we investigated patients diagnosed with early-stage lung cancer (stage Ia/Ib) at our Department of Pulmonary Medicine in a university hospital in two consecutive years. We evaluated if there had been a clinical suspicion of lung cancer prior to the chest X-ray or the Computerised Tomography (CT scan), that led to the discovery of lung cancer, or if the lung cancer had been an incidental finding during the investigation for another disease.

Method

Data source

One-hundred-and-seventy-seven patients were diagnosed with clinical stage I lung cancer (TNM, 7th edition) at the Department of Pulmonary Medicine at Aarhus University Hospital in 2015 and 2016. Medical records of these 177 patients were retrospectively reviewed, focussing on the circumstances that led to referral to a CT scan and further examination. The patients were then divided into two groups, where incidental findings were compared to non-incidental findings (see below). The patients with incidentally discovered lung cancer were further subdivided into those with and without symptoms.

Details about referral, tumour size, tumour histology, etc. as well as patient characteristics with regards to chronic and/or malignant comorbidity and smoking habits were registered and compared between the groups.

Incidental and non-incidental finding

An incidental finding of lung cancer was registered when the CT scan leading to the diagnosis had been made for other reasons than suspicion of lung cancer, e.g., a heart scan or work-up for or control after treatment of another cancer. But although these patients had not been referred to a CT scan due to a clinical suspicion of lung cancer, some of them did, at their first visit to our clinic, report of symptoms that could be classified as suspicious for pulmonary malignancy. These patients were here still registered as incidental findings, as these symptoms were not known at the time of referral to the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, and had not led to an investigation on the suspicion of lung cancer.

Patients referred to a CT scan due to symptoms and clinical suspicion of pulmonary malignancy, were registered as non-incidental findings ().

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics and source of referral – divided into patients with incidentally discovered lung cancer and patients where the lung cancer was found because of a suspicion of lung cancer.

The patients were followed-up until death or for a maximum of 56 months after the diagnosis of lung cancer.

Ethics

The investigation was conducted as part of the quality assurance program at the department and was solely based on information found in the patients’ medical records. Such investigations do not require approval from the Ethical Committee.

Stastistics

Statistical analysis was made in STATA 16® (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Count distributions were evaluated with Chi-square or with Fisher’s exact test when individual expected cell counts were below 5.

Continuous variables with an approximately normal distribution, such as age and lung function, were described by mean and standard deviation and analysed with t-test statistics. Continuous variables with non-normal distribution, such as size of noduli, were described by their median and inter quantile range (IQR) and analysed and compared by Mann-Whitney test.

Survival was analysed in a Cox proportional hazards regression model with adjustment for gender and age.

Results

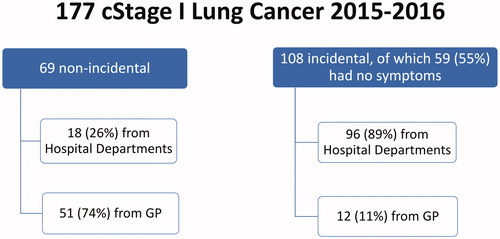

Of the 177 patients referred to the Pulmonary Department, 108 had been referred due to incidental discovery of nodules on a CT scan for various reasons other than clinical suspicion of lung cancer (incidental findings) (). The remaining 69 patients were referred to a CT scan due to lung and airways related symptoms as cough, expectoration, haemoptysis etc. (), that gave rise to a clinical suspicion of lung cancer (non-incidental findings).

Figure 1. A schematic presentation of where the 177 patients diagnosed with clinical Stage I lung cancer in 2015–2016 at the Department of Pulmonary Medicine at Aarhus University Hospital came from, divided into whether the lung cancer had been found incidentally or non-incidentally. It is also indicated how many of the patients with incidentally discovered lung cancer that had no symptoms.

Both groups had more men than women while in terms of age, smoking history and lung function the two groups were similar ().

In we have listed the patients’ comorbidities with regards to chronic diseases and malignancies.

In the incidental group 71% of the patients had chronic comorbidity compared to 90% in the non-incidental group (p < .005). The opposite applied to malignant comorbidities. Patients in the incidental findings group more frequently had other cancers as well as their lung cancer. Especially head-and-throat cancer, renal and urinary cancer and gastrointestinal cancer were overrepresented in the incidental group compared to the non-incidental group. ‘Other cancers’ than those specifically mentioned in were also overrepresented in the incidental group. Thirty-seven percent in the incidental group and twenty-two percent in the non-incidental group had both chronic and malignant comorbidity.

Patients were referred either from a General Practitioner (GP), a hospital department other than the pulmonary department, or other clinics within the pulmonary department, such as the clinic for patients with chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) ( and ).

Among the 63 patients referred from their GP, 51 patients had been referred due to clinical suspicion of lung cancer (non-incidental finding). These patients made up 74% of all patients with non-incidental findings of lung cancer, while only 12 patients with incidental findings had been referred from their GP to the CT scan on which the lung cancer was discovered ().

Referral from a hospital department other than a pulmonary department was more often the result of an incidental finding of lung cancer, 89 vs 15 patients of the 104 patients referred from these departments. Patients referred to a CT scan from other hospital departments constituted 82% of all incidental findings and only 24% of all non-incidental findings. Seven percent of all incidental findings and four percent of all non-incidental findings were due to referral from a pulmonary department ().

Although patients were referred to our department due to incidental findings on a CT scan and not due to a primary clinical suspicion of lung cancer, 45% of the patients actually did report of symptoms possibly related to lung cancer at their first consultation. These symptoms were not known by the pulmonologist prior to the first meeting with the patient and had not led to an investigation on the suspicion of lung cancer. Twenty-three percent of these patients had more than one symptom and 19% also had B-symptoms (night sweats, weight loss, fatigue) compared to 44% with B-symptoms in the non-incidental group (). Thus, markedly fewer patients in the incidental group had B-symptoms compared to the non-incidental group.

After the initial CT scan leading to the suspicion of lung cancer, a proportion of patients were referred to a new CT scan in the following months instead of further examinations for lung cancer right away. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in this regard.

Some of the patients had repeated CT scans every few months as follow-up. Patients in the incidental group had repeated CT scans for follow-up for a median of 9 months and the non-incidental patients for a median of 10 months ().

Table 2. Differences between tumours in patients with incidentally and non-incidentally found lung cancer and difference regarding CT follow-up before cancer work-up.

Patients who were referred to a CT scan follow-up had in the incidental group a median tumour size at the first CT scan of 11 mm (IQR: 9–15), which was comparable to the tumour size in patients in the non-incidental group with a median tumour size of 11 mm (IQR: 9–19) (p = .89).

Within the two groups, we found no difference in tumour size when comparing patients with B-symptoms vs. no B-symptoms. In the incidental group the patients with B-symptoms had a median tumour size of 17.5 mm (IQR: 11–24) compared to patients with no B-symptom with a tumour size of 19 mm (IQR: 12–27) (p-value .49). Tumour size in patients in the non-incidental group with B-symptoms was 21.5 mm (IQR: 14–28) compared to 20 mm (IQR: 16–30) in patients with no B-symptoms (p-value .66)

At the time when a follow-up CT scan led to the decision to initiate diagnostic work-up, the tumour had grown in both groups. In the incidental group the median tumour size was then 16 mm (IQR: 12–21) and in the non-incidental group the median tumour size was 18 mm (IQR: 13–25), (p = .46) which is equivalent to a median tumour growth of 4 mm (IQR: 1–6) for the incidental group and 4 mm (IQR: 3–7) for the non-incidental group (p = .28).

In both groups the majority was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma and fewer with squamous cell carcinoma or other histological types of lung cancer. In both groups the majority were diagnosed with lung cancer in stage Ia rather than Ib ().

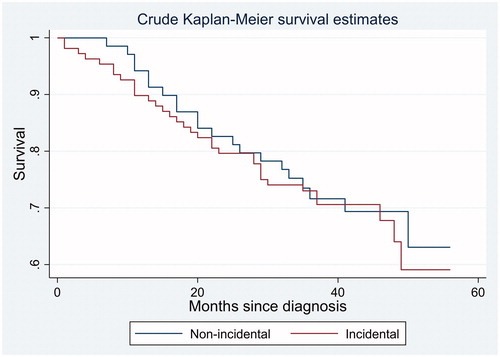

Fifty-five patients died during follow-up. The remaining patients were followed for between 29 and 56 months after the diagnosis of lung cancer. With regards to overall survival after the diagnosis of lung cancer, we found no statistically significant difference between patients with an incidentally discovered lung cancer versus those with non-incidental lung cancer in a Cox regression analysis, with correction for gender, age, and the presence of symptoms at time of diagnosis (HR = 1.1, 95% CI: 0.57−2.11) (). Neither was there in the same Cox regression model any indication that the 59 patients without any symptoms had a better survival compared to those with symptoms (HR = 1.03. 95% CI: 0.52–2.03).

Discussion

In our study we found that 61% of all lung cancers diagnosed in stage I in our department were found incidentally. This is a considerably higher proportion than in three previous studies which report the rate of incidental findings as 19% [Citation5], 45% [Citation6] and 50% [Citation4]. The latter two only regard patients who were surgically resected for their cancers, whereas the first study included all patients diagnosed with lung cancer in one centre over a period of time which is a design comparable to ours. However, in all three studies, and particularly in Kocher et al. [Citation5], there is a very stringent definition of ‘incidental find’, where there should be no symptoms attributable to lung cancer at the time of diagnosis. This can most likely explain the difference to our findings as we used a wider definition of incidental findings which does not regard the presence of symptoms at time of diagnosis, but rather the clinical suspicion of lung cancer or not prior to referral. We find it to be more clinically relevant, when evaluating the circumstances leading up to cancer work-up, if the presence of symptoms or not should be used to guide and improve our handling of the patients when they are referred to us.

Our information with regards to patient symptoms, comes mostly from patient records from their first visit at the pulmonary department since referral documents rarely contained sufficient clinical information. However, in both the incidental and non-incidental group, a moderate proportion had been monitored in a CT scan follow-up of varying lengths (up to 40 months) before the diagnostic work-up for lung cancer was initiated. Some of these patients were not seen at the pulmonary department at the time of the initial scan, if the pulmonary nodule was initially deemed to be too small for invasive diagnosis or considered to be non-malignant, and only came to the department when the nodule in question was found to progress on a follow-up scan. Therefore, some patients may potentially have gone from asymptomatic to symptomatic in the intervening time. Nonetheless, this does not change our classification of incidental vs. non-incidental find, as pertains to the reason for initial referral for CT.

As stated, previous studies have found a better survival rate in patients with incidentally found (defined as asymptomatic at time of diagnosis) lung cancer [Citation4–6]. We did not find any difference in survival even though 55 patients (31%) died during the observation period. As seen in there was no indication of an evolving difference in mortality between the two groups.

Overall, the group of patients with incidentally found lung cancer was comparable to the non-incidental group regarding age, sex, smoking and tumour size. However, there was a statistically significant difference regarding co-morbidity, where the incidental group had a much higher prevalence of other malignancies (57% vs 26%), while the non-incidental group had higher prevalence of non-malignant co-morbidity (90% vs 71%), particularly pulmonary co-morbidity.

The high amount of malignant co-morbidity in the incidental group, can probably be partially explained by the fact that work-up or control for other cancers often include CT scans of parts or the entire lungs. Thus 23% of all the incidentally found cancers, were discovered during work-up for other malignancies. Many of these patients might have been diagnosed considerably later, if not for this work-up. On the other hand, it can also be theorised, that symptoms that might stem from a lung cancer, is instead attributed to a patient’s already known cancer, as evidenced by the fact that 24 of the 42 patients who were found during work-up or control for another cancer, actually had symptoms that might derive from their lung cancer. Therefore, there is also a risk that some symptomatic lung cancers are overlooked due to other malignancies, since not all cancer work-ups/controls include a CT scan of the entire lung.

Among patients with incidentally diagnosed cancers, 45% actually did report symptoms, which might relate to lung cancer when asked. It is unclear whether their physicians were unaware of these symptoms, or if the symptoms were interpreted as being caused by another condition. Most incidentally found patients were referred from other hospital departments (82%), evenly distributed between work-up or control for other malignancies and other causes. This suggests that, to some extent, physicians were aware of the patients’ symptoms, and had instigated further examination. However, in our present study, we have not registered which other hospital departments our patients were referred from in the ‘other causes’ group, and neither which circumstances led to the initial radiological test (e.g., cardiac CT, urography etc.). Therefore, we are unable to determine how many patients were referred to another department because of symptoms that might relate to their lung cancer.

There was a higher proportion of pulmonary co-morbidity among patients with non-incidentally found lung cancer which was statistically significant. There was, however, no overall difference in smoking or lung function between the two groups. This might be because patients with known pulmonary disease are more prone to visit their GP or the hospital, and that GPs are more aware of the risk of lung cancer in patients diagnosed with COPD. This also matches our finding, that the majority of non-incidentally found lung cancers were referred from their GP. It could have been feared that symptoms of lung cancer would be overlooked in patients with pulmonary disease, but we found no difference between our two groups with regards to proportion of patients with pulmonary symptoms and pulmonary disease. So, despite the fact that symptoms of lung cancer are often non-specific and common in primary care, GPs seem to be aware of them in patients with pulmonary disease.

Limitations in this study

Since we only have information on patients with lung cancer which, after full diagnostic work-up, were staged as stage I, we are unable to say, if some potential stage I cancers were up-staged during the CT follow-up period rather than as a result of further work-up. We do, however, believe that to be a very small number, if any, as the follow-up would only be initiated for small nodulus and the follow-up intervals were according to international guidelines, which are well documented to ensure against radical shifts in stage, such as going from stage I to II or higher. We found no statistically significant difference between how many were sent into CT follow-up without a work-up between the incidental (29%) and non-incidental (25%) groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, with regards to need for different handling of patients with suspicion of early-stage lung cancer, we found no difference in our handling of the two groups. Neither did we find any indication that a clinical suspicion of lung cancer prior to diagnostic work-up or the presence of symptoms led to a lesser survival rate.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Torre LA, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Lung cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:1–19.

- Danish Lung Cancer Registry [Internet] Denmark: Danish Lung Cancer Group. 2018; [cited 2021 Feb 6]. Available from: https://www.lungecancer.dk/rapporter/aarsrapporter/.

- Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Identifying patients with suspected lung cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(592):e715–e723.

- Raz DJ, Glidden DV, Odisho AY, et al. Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with surgically resected, incidentally detected lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(2):125–130.

- Kocher F, Lunger F, Seeber A, et al. Incidental diagnosis of asymptomatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a registry-based analysis. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17(1):62–67.

- Orrason AW, Sigurdsson MI, Baldvinsson K, et al. Incidental detection by computed tomography is an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients operated for nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. ERJ Open Res. 2017;3(2):00106–2016.

- Quadrelli S, Lyons G, Colt H, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of incidentally detected lung cancers. Int J Surg Oncol. 2015;2015:1–6.