Abstract

Background

With increased survival among patients with metastatic melanoma and limited time with health care providers, patients are expected to assume a more active role in managing their treatment and care. Activated patients have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to make effective solutions to self-manage health. The use of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) could have the potential to enhance patient activation. However, PRO-based interventions that facilitate an activation in patients with metastatic melanoma are lacking and warranted.

Material and methods

In this prospective non-randomized controlled, clinical trial, patients with metastatic melanoma were assigned to either the intervention (systematic feedback and discussion of PRO during consultation) given at one hospital or the control group (treatment as usual) if they received treatment from two other hospitals in Denmark. The primary outcome was the patient activation measure (PAM), which reflects self-management. Secondary outcomes were health-related quality of life (HRQoL), self-efficacy, and Patient–Physician interaction. Outcomes were measured at baseline, and after 3, 6, and 12 months. The analysis of the effect from baseline to 12 months employed mixed-effects modeling.

Results

Between 2017 and 2019, patients were allocated to either the intervention group (n = 137) or the control group (n = 142). We found no significant difference in the course of patient activation between the two groups over time. The course of HRQoL was statistically significantly improved by the intervention compared to the control group. Especially, females in the intervention group performed better than males. The other secondary outcomes were not improved by the intervention.

Conclusion

The intervention did not improve knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management for patients with metastatic melanoma. Neither did it improve coping self-efficacy nor perceived efficacy in Patient–Physician interaction. However, the results suggest that the intervention can have a significant impact on HRQoL and in particular social and emotional well-being among the females.

Background

Over the past 5 years, therapeutic management of metastatic melanoma has changed significantly and thus led to improved survival [Citation1–3]. However, patients receiving treatment for metastatic melanoma may experience several side effects, limitations of lifestyle and activities, fear, and thoughts of death, all of which have an impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [Citation4–6]. Furthermore, with ongoing survivorship among cancer patients and limited time with health care providers, patients are expected to assume a more active role in managing their treatment and care [Citation7,Citation8]. To take up this responsibility, patients need to become aware of symptoms that require action, be able to raise issues of importance, and be engaged in their own treatment and care. This calls for a focus on self-management of cancer in everyday life and HRQoL.

The use of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) has the potential to enhance patient engagement and self-management [Citation9]. PRO is a health status assessment elicited directly from patients without any alteration or interpretation of the patient’s response [Citation10]. Typically, both symptoms and HRQoL are included in PRO-measures [Citation11]. In clinical practice, PRO-measurement at an individual level can be used to facilitate the detection and management of physical or psychological problems, improve patient-clinician communication, and as a means to establish patient-centered care by facilitating a focus on the patient’s perspective [Citation12–18]. The patient-centered element may induce patient involvement in decisions about their care. This may increase patients’ ability to manage their own health and could contribute to increased patient satisfaction, self-management, and improved health outcomes [Citation9]. When it comes to the impact of PRO on patient outcomes, the evidence is less consistent [Citation18–20].

Activated patients are patients who have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to make valuable solutions to self-manage their health [Citation21]. Studies have shown that more activated patients are likely to be better informed and more proactive about managing their condition, symptoms, and side effects [Citation7,Citation22]. These findings suggest that activation is changeable [Citation23], thus improving activation has promising potential. Access to and adequate time spend with providers are associated with activation in both breast and prostate cancer survivors [Citation24]. Therefore, clinical interventions that facilitate systematic and patient-centered consultations may be a promising avenue to improve patient activation. PRO-based interventions that facilitate activation in patients with metastatic melanoma are lacking and warranted.

We aimed to investigate the potentials of using PRO as a dialogue-based tool in consultation with patients with metastatic melanoma. We hypothesized: (1) an improvement of patients’ knowledge, skills, and confidence in self-managing health and care, (2) a reduction of perceived burden of physical symptoms and emotional dysfunction, and (3) improvement of the Patient–Physician interaction.

Material and methods

Design

In this prospective non-randomized controlled, clinical trial, patients were assigned to either the intervention (systematic feedback of completed PRO-measures to physicians during each consultation) or the control group (treatment as usual without any use of PRO-measures in the consultation). No extra time was allocated for consultations in any of the two groups. The intervention took place at the Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. Patients in the control group were recruited from two other departments in Denmark treating patients with metastatic melanoma (Odense University Hospital and Herlev Hospital). All patients were recruited from June 2017 to July 2019. Outcomes were measured at baseline, and after 3, 6, and 12 months using the following questionnaires: Patient Activation Measure (PAM), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Melanoma (FACT-M), Cancer Behavior Inventory – Brief Version (CBI-B), Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interaction (PEPPI).

Five patients with metastatic melanoma participated in the trial’s patient advisory board as patient research partners. Together with researchers, they engaged in selecting PRO-measures, writing of the information materials, designing and analyzing an intervention fidelity study, and disseminating trial results [Citation25].

Subjects

Danish patients with verified metastatic melanoma were eligible if they were to receive treatment for their metastatic melanoma (regardless of time since treatment start and severity of disease), had a life expectancy longer than 2 months, were fluent in Danish, and were willing to complete repeated questionnaires. Patients were invited to participate in the trial and informed about the aim and procedures by their oncologist or a trained nurse when visiting the oncology department.

Ethics

The project was approved by the Danish data protection agency. According to the Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects in Denmark, the trial was exempted from ethical approval due to the intervention being questionnaires. Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03163433.

The intervention

All patients in the intervention completed a dialogue tool consisting of electronic PRO-measures and an open-ended field for their most important issues. The completion took place before every consultation with a physician at the outpatient clinic and could be performed from home or from a designated tablet in the waiting room in the clinic. PRO-data was transferred in real-time into patients’ electronic medical records via The AmbuFlex/WestChronic system and was available for physicians to assess before the consultation. Feedback was provided employing a bar chart with color-status indicating the severity of the reported issue [Citation26] (‘green’ indicated no problems, ‘yellow’ mild, ‘orange’ moderate, and ‘red’ severe burden) and a special focus on the patient-reported important issues. All physicians at the intervention site received training in patient-centered communication based on PRO in clinical cancer settings. The physicians were taught to focus and comment on PRO-data including the answers from the open-ended question, and suggestions on how to do so were given. The training consisted of a one-hour training session including an associated 1-page manual, and ad hoc training in the clinic. The development of the training tool has been reported elsewhere [Citation27].

PRO-measures in the intervention

The dialogue-based tool consisted of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Core Quality of Life Questionnaire, version 3.0 (EORTC QLQ-C30) (in Danish) [Citation28,Citation29], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (in Danish) [Citation30,Citation31]. We chose the 30-item EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire, because it is widely used in cancer settings [Citation15,Citation32] and the patient research partners considered it reliable to capture their cancer-related experiences. However, they needed a stronger focus on worries and concerns and considered the HADS relevant. HADS is a 14-item measurement consisting of subscales for anxiety and depression.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was PAM [Citation21,Citation33], which describes the knowledge, skills, and confidence a person has in managing health and care and reflects attitudes and approaches to self-management. Therefore, PAM was considered an appropriate outcome measure. The scale consists of 13 items translated into Danish [Citation34]. Each item is rated on a four-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree (an option for ‘non-applicable’ is available). A score is transformed to a scale with a range of 0–100, with higher PAM scores indicating higher activation. Scores can be used to track individual changes over time. A clinically meaningful change in PAM varies in the literature between 2-point [Citation35] to 4 to 8-point [Citation36]. According to the lead author on PAM, an average net 6-point PAM score increase in a period of 6–12 months is considered an ‘excellence’ score [Citation37]. We choose 6-point as an indicator of a meaningful change.

FACT is a validated catalog of assessment instruments [Citation38]. FACT-General (FACT-G) consists of four quality of life domains: physical well‐being (PWB), emotional well‐being (EWB), social/family well‐being (SWB), and functional well-being (FWB). In total, the FACT-G questionnaire contains 27 items and a higher score indicates better HRQoL (score range, 0 to 108). A validated melanoma-specific module can be added to FACT-G resulting in FACT- M [Citation5,Citation39]. FACT-M consists of FACT-G and adds an additional 16 items (score range, 0–172). Minimal important differences (MIDs) for the FACT-M have been assessed to be 4–6 points [Citation40]. The FACT-M questionnaire (version 4) was a natural choice as it is widely used in similar clinical trials [Citation15].

CBI-B is a 14-item unidimensional instrument designed to assess the coping self-efficacy of cancer patients [Citation41,Citation42]. Each of the 14 items is rated on a scale of 1 (Not at all confident) to 9 (Totally confident). The CBI-B score is calculated as the sum of all 14 answered items and can range from 14–126. A higher score indicates higher coping self-efficacy. No minimal clinically important difference analyses have been performed yet.

PEPPI consists of five items used to assess the patient-perceived efficacy in the Patient–Physician interaction [Citation43]. Total scores of the PEPPI-5 are summed to range from 0 to 50, with higher scores representing higher perceived self-efficacy in Patient–Physician interactions. No minimal clinically important difference analyses have been performed yet.

Statistical analysis

With a power of 80%, α of 0.5, SD of 16.5, clinical meaningful change of 6-point in PAM, and allowing for 15% attrition, 282 patients equally divided between intervention and control group were needed to power the result. Baseline data on participating patients and declining patients were tabulated and examined for imbalances between the groups by applying Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Fisher’s exact test, and a test for 50% in each group. Analysis of the effect over time employed linear mixed-effects models including fixed effects for the group, time, and the interaction between group and time, and a random effect for the patient. For subgroup analysis, the interaction term was expanded to include the covariate. Multivariate linear mixed-model analyses were employed to adjust for possible confounding due to baseline differences between the intervention and control group. The effect of the intervention was measured at 12 months post-baseline as the difference between differences to baseline. PAM, FACT-G/M, CBI-C, and PEPPI scores were adjusted for the number of missing values and normalized to 0–100 prior to analysis. Samples were included if they had more than 10 out of 13 questions answered for PAM, more than 80% of the questions answered for FACT-G/M, CBI-B, and PEPPI, and 3 out of 5 questions answered for the four FACT QoL subdomains. p < 0.05 was considered significant and data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

Results

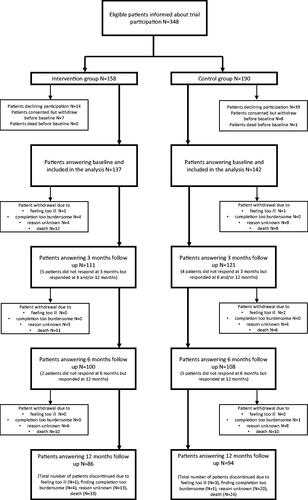

A total of 348 patients with metastatic melanoma were informed about the project. Among these, 279 patients were included in the baseline analysis, 53 patients declined participation and 16 withdrew before completing the baseline questionnaire, due to other circumstances. The participant flow is illustrated in . In total, 137 patients entered the intervention group and 142 patients entered the control group. Death was the main reason for drop out of the study. During the study period, 57 (20%) patients died, and 42 (15%) patients dropped out due to other circumstances. Despite reminders, the attrition rate was 35.5%

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics (demographic, psychosocial, and treatment-related factors) are presented in . Most patients in the intervention group were male (63%), whereas the majority of patients in the control group were female (53%) (p = 0.011). In the intervention group, most patients (48%) were diagnosed with metastatic melanoma within the last 6 months before baseline, whereas in the control group, most patients (56%) were diagnosed more than 12 months before baseline (p > 0.0001). In the intervention group, more patients received targeted therapy (23%) compared to the control group (13%) (p = 0.0052). All other baseline parameters were equal between the two groups. Additionally, patients who declined participation did not differ statistically in mean age, sex, or treatment compared to participating patients (see Supplementary material 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics at baseline.

Outcomes

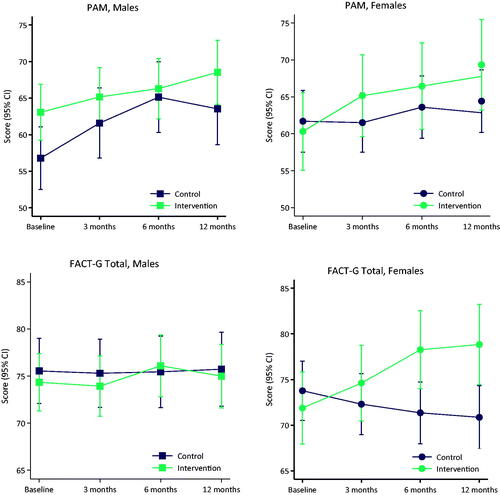

The results of the primary and secondary outcomes are shown in . We found no significant difference in the course of patient activation between the intervention group and the control group over time (difference at 12 months 2.3 [95% CI −2.8 to 7.4; p = 0.37]; ). The course of HRQoL-data was statistically significantly different between the intervention group and the control group over time (difference at 12 months 4.6 [95% CI 1.7 to 7.6; p = 0.0019] for FACT-G and 3.8 [95% CI 1.2 to 6.5; p = 0.0045] for FACT-M; ). The patients in the intervention group performed statistically significantly better over time both socially and emotionally than the control group (). No significant differences were found between the intervention group and control group on the course of CBI (difference at 12 months 2.0 [95% CI −1.9 to 6.0; p = 0.31]; ) or PEPPI (difference at 12 months −1.8 [95% CI −6.3 to 2.6; p = 0.42]; ) over time. In the intervention group, a positive course over time is seen in all outcomes. Mean values for patients in both groups at baseline are not equal on the PAM and PEPPI scales, both with higher values (better baseline outcomes) for patients in the intervention group. For PEPPI, no effect of the intervention is seen, but noteworthy all mean scores for the intervention group are higher than mean scores for the control group (). Adjustments for possible confounding due to baseline differences between the groups showed no significant differences in any of these outcome results (Supplementary materials 2).

Table 2. Results of linear mixed-model analyses on primary and secondary outcomes.

Sub-group analyses

The course of PAM over time showed equality of effects for all covariates (sex, age, education, employment, cohabitation, comorbidity, physical well-being) between the intervention group and control group (see Supplementary material 3). Data indicate a larger effect of the intervention for females concerning self-management (higher PAM-scores) (effect of intervention at 12 months 6.3 [95% CI −1.6 to 14.3]) than for males (effect of intervention at 12 months −1.3 [95% CI −8.2 to 5.6]) but the result is not statistically significant (p = 0.16). The same trend (females performing better than males) was seen in almost all other secondary outcomes (except PEPPI), most profound in HRQoL where females performed statistically significantly better (effect of intervention at 12 months for FACT-G 9.9 [95% CI 5.5 to 14.2]) than males (effect of intervention at 12 months for FACT-G 0.5 [95% CI −3.6 to 4.6]) with a p-value of 0.0020. This trend is illustrated in . Adjustments for possible confounding due to baseline differences between groups showed no significant differences in any of the results from the sub-group analysis (Supplementary materials 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate whether an intervention consisting of a PRO-based dialogue tool could support patients with metastatic melanoma in self-management.

We did not find a statistical effect of the intervention on the primary outcome (PAM). The high PAM scores found at baseline may have impacted this result. High PAM scores are in line with other studies examining PAM in patients with cancer [Citation24,Citation44–46]. PAM scores seem to be higher in patients with cancer than in patients with other chronic conditions [Citation47]. It is debatable if high baseline PAM scores can be expected to increase further in a population that may face progression of the disease, changes in treatments, and psychological distress [Citation48,Citation49]. These difficulties may lead to a temporary decrease in self-management [Citation35]. The suitability of PAM in our population must also be questioned. Previous research on patient activation has focused on chronic illnesses such as diabetes. Yet, the role of the measure in cancer populations, and in particular those undergoing immunotherapy and chemotherapy is less clear and studies are cross-sectional [Citation7,Citation24,Citation46]. However, a meaningful change (>6 point change of PAM-score) was suggested for the intervention group (from baseline to 12 months, the difference in mean change in PAM scores was 6.1 points in the intervention group and 3.8 points in the control group).

The found effect on HRQoL and not on PAM is similar to another study aiming at supporting patients in self-management by reporting and monitoring symptoms over time [Citation45]. This could indicate that PRO interventions in clinical practice do not enhance knowledge, skills, and confidence to self-manage but they have the potential to support cancer patients in improving HRQoL and minimizing symptom burden. This is in line with other studies showing that web-based self-management interventions can have a positive effect on HRQoL and symptom burden in patients with cancer [Citation50–52]. We found that females might benefit more from the intervention than males perhaps leading to better self-management and HRQoL for women. In other studies though, female sex is not associated with increased patient activation [Citation53,Citation54]. The statistically significant effect on HRQoL between females in the intervention and females in the control group seemed clinically relevant (mean difference between females in the two groups was 9.9 points (4–6 points were associated with MIDs)). However, in the present study, no power calculation was performed to detect a difference in secondary outcomes such as HRQoL. Hence, results should be interpreted with caution.

A strength of this present trial is its closeness to daily clinical practice, as the intervention was integrated into normal procedures, and our wide inclusion criteria yielded representation of a typical patient with metastatic melanoma. In addition, the sustainability of a long-term commitment to the dialogue tool is noticeable. This enhances its relevance to decision-makers and health care professionals. Another strength is the effort to make the intervention implementable, systematic, and consistent by training physicians. Primarily, three physicians consulted patients in the intervention. One of whom was part of the development of the dialogue tool. The physicians were engaged and took ownership of the trial.

This study must be seen considering some limitations. Our results were based on a non-randomization design which entails the risk of selection bias. Differences in treatment and care may be present according to the different study sites, which may represent the risk of bias. Baseline differences in ‘treatment’ and ‘time since diagnosis of metastatic disease’ were probably due to the non-randomization design. These confounders increase the uncertainty of the effect of the intervention. We also found differences in ‘sex’ (a smaller proportion of females in the intervention group compared to the control group). Generally, gender differences in patients with cancer tend to show higher self-reported HRQoL in males (less impaired function) than females [Citation55,Citation56]. Our results show the same trend at baseline, but interestingly, females seem to benefit most from the intervention. The non-randomization design was chosen to avoid the carry-over effect and contamination of the control group. The trained physicians could have passed an increased focus on patient-centered communication to the control group. Additionally, the non-randomization design was believed to secure a uniform intervention that could otherwise depend on different physician accesses to the PRO data and ad hoc training.

Another limitation is our focus on patient-reported outcomes alone and no objective registration of clinical parameters such as performance status, brain metastases, LDH-level, or treatment response were captured. These parameters could have contributed to a nuanced picture of the results, and an easier translation into clinical practice. Additionally, no thorough evaluation of the adherence to the intervention was performed. However, to check intervention fidelity, a random sample of six consultations was audio-recorded. The analysis of these consultations showed that PRO-data was used as intended in all audiotaped consultations [Citation25]. Other studies have found a high willingness among cancer patients to report PROs in clinical practice [Citation13,Citation57,Citation58]. A study on patients’, nurses’, and physicians’ perceptions of a system for electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring during routine cancer care showed that they all found PRO data useful to guide discussions and to make treatment decisions [Citation59]. Contrary, low physician adherence to the protocol for a study on PROs in a fragile and comorbid cancer population has been found [Citation60]. Low physician adherence could prevent patients from raising and discussing their concerns leading to a presumably lower level of knowledge and acquisition of self-management skills. Furthermore, an attrition rate of above 30% was observed. This is similar to other longitudinal studies [Citation14,Citation15], but attrition was higher in the intervention group than in the control group, which might have affected the results. The high attrition rate in combination with the exclusion of patients from the analysis, when they completed less than 10 out of 13 questions in the PAM questionnaire resulted in 180 patients in the PAM analysis (86 in the intervention and 94 in the control group). The study was powered to detect a change in PAM with 282 patients (allowing for 15% attrition). The results must therefore be considered with caution.

Besides deaths, dropouts in the study were mainly based on unknown reasons. The possibility of the intervention being too hard on the patients cannot be ignored. This is an interesting subject for further research. Likewise, an investigation of meaningful use of the PRO-based dialogue tool is warranted. Progression of disease and entering the terminal phase of life may not be in accordance with spending time on completing a dialogue tool. Our study also generates new questions for understanding ways in which patients and physicians interact with PRO, and how this might influence efficacy.

Conclusion

The intervention with a systematic focus on patient-centered communication through the use of a PRO-based dialogue tool did not statistically improve knowledge, skills, and confidence for self-management for patients with metastatic melanoma although a trend toward a meaningful improvement was observed. Neither did it improve coping self-efficacy nor perceived efficacy in Patient–Physician interaction. However, the results suggest that the intervention can have an impact on HRQoL and in particular social and emotional well-being among females.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (288.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank clinicians from participating departments and especially the participating patients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pasquali S, Hadjinicolaou AV, Chiarion Sileni V, et al. Systemic treatments for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2018;2:CD011123.

- Michielin O, van Akkooi ACJ, Ascierto PA, et al. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(12):1884–1901.

- Michielin O, Hoeller C. Gaining momentum: new options and opportunities for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41(8):660–670.

- Weitman ES, Perez M, Thompson JF, et al. Quality of life patient-reported outcomes for locally advanced cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2018;28(2):134–142.

- Cormier JN, Davidson L, Xing Y, et al. Measuring quality of life in patients with melanoma: development of the FACT-melanoma subscale. J Support Oncol. 2005;3(2):139–145.

- Dunn J, Watson M, Aitken JF, et al. Systematic review of psychosocial outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma. Psychooncology. 2017;26(11):1722–1731.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney E, Sonet E. Does patient activation level affect the cancer patient journey? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1276–1279.

- McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(1):50–62.

- Santana MJ, Feeny D. Framework to assess the effects of using patient-reported outcome measures in chronic care management. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(5):1505–1513.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79.

- Weldring T, Smith SM. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Health Serv Insights. 2013;6:61–68.

- Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1480–1501.

- Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565.

- Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and Patient–Physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(23):3027–3034.

- Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):714–724.

- Greenhalgh J, Dalkin S, Gooding K, et al. Functionality and feedback: a realist synthesis of the collation, interpretation and utilisation of patient-reported outcome measures data to improve patient care. Southampton (UK) NIHR journals library. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2017;5(2):1–280.

- Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:122–134.

- Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcome measures on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:211.

- Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, et al. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(2):179–193.

- Marshall R, Beach MC, Saha S, et al. Patient activation and improved outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(5):668–674.

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the patient activation measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4):1005–1026.

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):207–214.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, et al. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1443–1463.

- O’Malley D, Dewan AA, Ohman-Strickland PA, et al. Determinants of patient activation in a community sample of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2018;27(1):132–140.

- Skovlund PC, Nielsen BK, Thaysen HV, et al. The impact of patient involvement in research: a case study of the planning, conduct and dissemination of a clinical, controlled trial. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:43.

- Hjollund NHI. Fifteen years’ use of patient-reported outcome measures at the group and patient levels: trend analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(9):e15856.

- Skovlund PC, Ravn S, Seibaek L, et al. The development of PROmunication: a training-tool for clinicians using patient-reported outcomes to promote patient-centred communication in clinical cancer settings. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):10.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MAG, et al. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):441–450.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

- Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(9):1846–1858.

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6):1918–1930.

- Maindal HT, Sokolowski I, Vedsted P. Translation, adaptation and validation of the American short form patient activation measure (PAM13) in a Danish version. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):209.

- NHS [Internet]. Patient activation and PAM FAQs England. London (UK): NHS; 2020 [cited 2020 October 30]. Available from https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/supported-self-management/patient-activation/pa-faqs/#Q1

- Altshuler L, Plaksin J, Zabar S, et al. Transforming the patient role to achieve better outcomes through a patient empowerment program: a randomized wait-list control trial protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e68.

- National Quality Forum [Internet]. Gains in patient activation (PAM) scores at 12 months. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2016 [cited 2020 November 25]. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579.

- Cormier JN, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prospective assessment of the reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-melanoma questionnaire. Cancer. 2008;112(10):2249–2257.

- Askew RL, Xing Y, Palmer JL, et al. Evaluating minimal important differences for the FACT-Melanoma quality of life questionnaire. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1144–1150.

- Heitzmann CA, Merluzzi TV, Jean-Pierre P, et al. Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the cancer behavior inventory (CBI-B). Psychooncology. 2011;20(3):302–312.

- Warrington L. Routine self-reporting of symptoms and side effects during cancer treatment: The patient’s perspective [PhD thesis]. Leeds (UK): University of Leeds; 2018.

- Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, et al. Perceived efficacy in Patient–Physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(7):889–894.

- Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, et al. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff. 2015;34(3):431–437.

- van der Hout A, van Uden-Kraan CF, Holtmaat K, et al. Role of eHealth application oncokompas in supporting self-management of symptoms and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors: a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(1):80–94.

- Salgado TM, Mackler E, Severson JA, et al. The relationship between patient activation, confidence to self-manage side effects, and adherence to oral oncolytics: a pilot study with Michigan oncology practices. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(6):1797–1807.

- Bos-Touwen I, Schuurmans M, Monninkhof EM, et al. Patient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey study. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126400.

- Whitman ED, Liu FX, Cao X, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma in US oncology clinical practices. Future Oncol. 2019;15(5):459–471.

- Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1415–1427.

- Warrington L, Absolom K, Conner M, et al. Electronic systems for patients to report and manage side effects of cancer treatment: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e10875.

- Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, et al. Self-management education interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1323–1355.

- Fridriksdottir N, Gunnarsdottir S, Zoëga S, et al. Effects of web-based interventions on cancer patients’ symptoms: review of randomized trials. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):337–351.

- Van Bulck L, Claes K, Dierickx K, et al. Patient and treatment characteristics associated with patient activation in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):126.

- Hendriks SH, Hartog LC, Groenier KH, et al. Patient activation in type 2 diabetes: does it differ between men and women? J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:1–8.

- Laghousi D, Jafari E, Nikbakht H, et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among patients with colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10(3):453–461.

- Page BR, Guo Y, Han P, et al. Quality of life differences in male and female patients with head and neck cancer. Int J Radiation Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(3):e741.

- Basch E, Wood WA, Schrag D, et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of sharing patient-reported symptom toxicities and performance status with clinical investigators during a phase 2 cancer treatment trial. Clin Trials. 2016;13(3):331–337.

- Girgis A, Durcinoska I, Levesque JV, et al. eHealth system for collecting and utilizing patient reported outcome measures for personalized treatment and care (PROMPT-Care) among cancer patients: mixed methods approach to evaluate feasibility and Acceptability. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(10):e330.

- Basch E, Stover AM, Schrag D, et al. Clinical utility and user perceptions of a digital system for electronic patient-reported symptom monitoring during routine cancer care: findings from the PRO-TECT Trial. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:947–957.

- Taarnhøj GA, Lindberg H, Dohn LH, et al. Electronic reporting of patient-reported outcomes in a fragile and comorbid population during cancer therapy – a feasibility study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):225.