Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease with a close association between incidence and mortality. First-line (FL) palliative chemotherapy prolongs survival and alleviates cancer-related symptoms. However, the survival benefit of second-line (SL) treatment is uncertain, as studies fail to consistently show prolonged survival for any given SL treatment, and in the absence of prognostic factors patients will receive a futile treatment. The aim of this study was to examine prognostic factors and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer, with special reference to SL therapy.

Material and methods

This retrospective study included all patients with histopathologically verified pancreatic adenocarcinoma who received palliative chemotherapy at Skåne University Hospital and died between 1 Feb 2015 and 31 Dec 2017.

Results

During the study period, a total of 170 patients with pancreatic cancer died after receiving palliative chemotherapy. Of these, 72 had received SL treatment after progression on FL treatment. Median overall survival (OS) from the start of SL treatment was 5.0 months (95% CI: 4.0–6.1). Median OS was 2.9 months for patients with performance status 2 at start of SL treatment compared to 5.3 months for patients with performance status 0–1 (p = .03), and 3.5 months (95% CI: 3.0–5.4) in patients with hypoalbuminemia (<36 g/L) at the start of SL therapy compared to 8.0 months (95% CI: 5.3–11.1) for patients with normal albumin levels (p = .009). Weight loss during FL therapy, a doubling of CA 19-9 after FL therapy, and length of progression-free survival during FL treatment were not associated with survival following SL therapy.

Conclusion

Poor performance status and hypoalbuminemia are negative prognostic factors for survival on SL palliative treatment in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Possible gain in survival should be carefully considered before initiating SL chemotherapy.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease with a close association between incidence and mortality, causing 2000 cancer-related deaths annually in Sweden [Citation1]. In exocrine pancreatic cancer, 90% of the tumors are adenocarcinomas. Surgery with a curative intention is recommended for the 15–20% of patients who present with a resectable tumor. A review article from 2015 on the burden of pancreatic cancer in Europe, with a majority of patients from Scandinavia, showed a median overall survival (OS) of 4.6 months from date of diagnosis, including all stages of disease and all available interventions ranging from surgery and chemotherapy to exclusively best supportive care [Citation2]. The best reported median OS is 28 months (CI: 23.5–31.5), which was found in a study including patients eligible for adjuvant chemotherapy after radical surgery [Citation3].

Palliative chemotherapy in pancreatic adenocarcinomas

Monotherapy with gemcitabine was long the sole medical therapy for pancreatic cancer used in the palliative setting. When used in first-line (FL) palliative chemotherapy, gemcitabine prolongs survival and alleviates cancer-related symptoms [Citation4]. In randomized studies comparing monotherapy with gemcitabine to combination regimes, median survival increased from just below 7 months on gemcitabine alone to 11.1 months on the combination treatment FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin, irinotecan, leucovorin and fluorouracil) and 8.5 months on gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [Citation5,Citation6]. Today, FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine are given as FL palliative chemotherapy for patients with a good WHO performance status (PS) of 0–1. Monotherapy with gemcitabine is recommended for patients with PS 2 [Citation7]. For patients with PS 3, best supportive care is advocated [Citation8]. As a second-line (SL) treatment, the choice of regimen depends on the FL treatment that was given, with a switch to either gemcitabine ± nab-paclitaxel or FOLFIRINOX. Liposomal irinotecan has also shown effect in SL treatment after progression on gemcitabine-based FL treatment [Citation9]. Various studies have reported median OS from start of the SL regimen to death as ranging from 4.8 to 8.8 months [Citation10–12]. The longest median OS from start of palliative chemotherapy, including a SL treatment, has been reported to be 18 months (CI: 16.0–21.0) [Citation11], after treatment with FOLFIRINOX followed by nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine.

However, survival benefit on SL treatment is uncertain, as studies fail to consistently show prolonged survival from any given SL treatment [Citation13,Citation14]. Gill et al. found no increase in survival among patients treated with the combination of oxaliplatin and fluorouracil (5FU) compared to monotherapy with 5FU after progression on FL gemcitabine [Citation15]. On the contrary, Oettle et al. found an increase in survival after progression on FL gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with oxaliplatin and 5FU in SL versus 5FU alone [Citation16]. Dadi et al. found an increased survival in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer treated with a nab-paclitaxel-based SL therapy compared with a non-nab-paclitaxel-based SL therapy after monotherapy with gemcitabine in FL [Citation17]. It is a challenge for the treating physician to identify patients who might benefit from a SL treatment as opposed to those where such a treatment is futile, brings false hope, and causes unnecessary toxicity. Hence there is a need to explore possible prognostic factors for deciding when a SL treatment should be recommended. In 2016, Sinn et al. proposed several prognostic factors on the basis of a retrospective study of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer after progression of FL palliative chemotherapy, in order to improve the selection of patients eligible for SL therapy in whom a meaningful gain in survival could be expected [Citation18]. These factors included Karnofsky performance status, CA 19-9 level, and duration of FL chemotherapy treatment. Patients with a good Karnofsky performance status (90–100%) and normal CA 19-9 level (<37 U/mL) at the beginning of SL therapy, together with a duration of FL treatment longer than 4 months, were found to have a significantly better median OS of 9.3 months (95% CI: 6.5–12.1) compared to 2.7 months (95% CI: 1.9–3.5) for patients with Karnofsky performance status ≤80%, elevated CA 19-9, and short duration of FL treatment (˂4 months).

Bao et al. found in a study from 2018 that 40% of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer received palliative chemotherapy during the last 30 days of life [Citation19]. It is important to bear in mind the short expected survival for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. A tumor-specific therapy may not confer any gain in survival or symptom relief, but instead impair the patient’s quality of life (QoL) and end-of-life care. Treatment recommendations must be well substantiated, and so there is a need for robust prognostic factors to better support a realistic discussion on palliative treatment.

Aim

The aim of this study was to examine clinical characteristics in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy, evaluating prognostic factors and survival, with special reference to second-line therapy.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Swedish National Ethics Committee on 2 April 2019 (ref: 2019-01093).

Material and methods

The study included all patients with histopathologically verified pancreatic adenocarcinoma (ICD codes: C25.0–C25.3, C25.7–C25.9) who received palliative chemotherapy at the Department of Oncology, Skåne University Hospital, and died during the study period (1 Feb 2015–31 Dec 2017).

Medical records were consulted to extract date of death and patient‑specific information: age, gender, date of diagnosis, and extent of the disease (local or generalized) at the first visit to the department and at tumor progression on FL palliative chemotherapy. In patients with generalized disease, the number of metastatic sites were assessed; metastases to distant lymph nodes, liver, lung, bone, or ‘other’ were each regarded as different sites, and survival was analyzed according to 1 or >1 metastatic site. Primary surgery was noted as microscopically or macroscopically radical or not (R0, R1, or R2).

Chemotherapy

Data were collected regarding the chemotherapy regimens, number of treatment cycles of each regimen, number of lines of palliative chemotherapy, and the day of the last chemotherapy treatment. Only completed cycles of chemotherapy were counted. For gemcitabine with or without nab-paclitaxel, with a cycle length of 28 days and treatment given days 1, 8, and 15, all three treatments were required for the cycle to be regarded as given. Otherwise, it was excluded from analysis except if a maximum of one of the three treatments was skipped exclusively because of neutropenia. For a treatment to be regarded as truly adjuvant, the patient had to be disease-free at the therapy-assessment CT performed 24 weeks after the last treatment given with an adjuvant intention. In case of confirmed disease during the adjuvant treatment or at first follow-up one year postoperatively, the given regimen was instead regarded as FL palliative chemotherapy.

Laboratory data

Laboratory data were collected on CA 19-9 (U/mL), bilirubin (µmol/L), PS (0–4), serum albumin (g/L), and patient weight (kg) at the start of FL palliative chemotherapy and at the time of verified radiological progression. Level of albumin was dichotomized into normal (≥36 g/L) and hypoalbuminemia (<36 g/L). Only patients with bilirubin in the normal reference interval (<26 μmol/L) were included in the analysis of CA 19-9, and these were dichotomized into those with a doubled CA 19-9 level and those without. Regarding weight loss, patients were categorized into three groups with weight loss <5%, 5–<10%, and ≥10% from start to end of FL palliative therapy.

Treatment results and survival

Time to progression following FL chemotherapy was dichotomized into ≥100 days or <100 days. Response to treatment was generally evaluated with a CT scan three months after initiation of therapy.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were calculated as median and range for continuous variables, due to skewed distribution, and as number (%) for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to evaluate survival over time in the total study population and in subgroups. OS was defined as time between diagnosis and death, and OS following SL palliative chemotherapy was defined from the start of treatment to death, including only patients who initiated SL treatment due to disease progression on FL palliative chemotherapy. Patients for whom SL therapy was initiated due to toxicity on FL were thus excluded from the analysis. Log-rank tests were used to test for difference in survival between groups receiving SL palliative chemotherapy. Patients were excluded from the analysis if data on the specific prognostic factor were missing. All analyses were univariate, and were performed in version 4.0.2 of R.

Results

A total of 170 patients with pancreatic cancer who were treated with palliative chemotherapy at the Department of Oncology, Skåne University Hospital, died during the study period; all were included. Their median age was 68 years (range: 37–85), 90 of them were women, and the remaining 80 were men. Primary surgery with curative intent was performed in 30 patients (18%), resulting in a radical resection (R0) in 12 patients, an R1 resection in 14 patients, and no radicality (R2) in the remaining four patients. The 140 patients (82%) who were not operated on had either a generalized disease or a non-resectable tumor, or were in a non-operable condition (). Six of the 30 patients who were operated on had manifest disease at the time of their first visit to the Department of Oncology. Hence, at this first visit, 91 patients had metastatic disease, 55 patients had locally advanced disease, and the remaining 24 were planned for adjuvant postoperative chemotherapy. However, in 18 of the 24 patients there was evidence of disease before or at the 24-week evaluation scan, and so their treatment was regarded as FL palliative therapy. The remaining 6 patients were all diagnosed with recurrent disease at a later time point, and FL palliative therapy was then initiated ().

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics at the first visit at the Department of Oncology and at the start of second-line (SL) treatment after progression of first-line (FL) of palliative chemotherapy.

Palliative chemotherapy

First-line palliative chemotherapy

The main FL treatment regimens were gemcitabine single-drug (n = 88) and FOLFIRINOX (n = 59), followed by gemcitabine plus capecitabine (n = 14), gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (n = 7), and FLOX (n = 2). Of the 88 patients receiving gemcitabine as FL treatment, 60 received no further treatment, 10 went on to further palliative treatment, and 18 received gemcitabine with an initially adjuvant intention but were then found to have manifest disease during the treatment or follow-up and so their treatment was reevaluated as FL palliative therapy.

The total group of 170 patients received a median of 5 cycles of FL treatment (range: 1–24).

Progression-free survival was ≥100 days in 102 (60%) of the 170 patients on FL treatment, who were then regarded as responders.

Second-line palliative chemotherapy

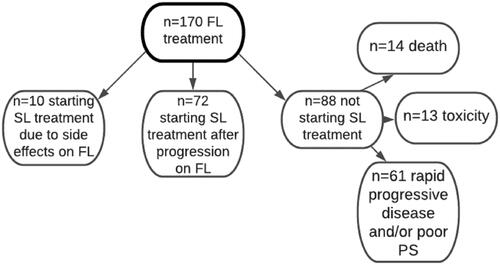

SL palliative chemotherapy after progression or toxicity on FL treatment was initiated in 82 patients (48%) (), 10 of whom (6%) switched to SL treatment due to side-effects on FL treatment (). The main SL regimens were gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (n = 22) and gemcitabine (n = 19), followed by oxaliplatin plus 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid (n = 9), FOLFIRINOX (n = 6), and other drugs and combinations (n = 16). A total of 88 patients did not receive any SL treatment; of these, 61 patients discontinued FL treatment due to rapidly progressing disease and/or poor PS, 14 patients because of death before radiological evaluation, and 13 patients due to toxicity (see and ).

Figure 1. Flowchart of all patients starting first-line (FL) palliative chemotherapy (n = 170). Of these, 88 (52%) did not start second-line (SL) treatment due to rapidly progressing disease and/or poor performance status (PS; PS 3–4; n = 61), death before radiological evaluation (n = 14), and toxicity (n = 13). Another 72 (42%) were treated with a SL therapy after progression on FL treatment. The 10 (6%) patients who received SL treatment due to toxicity on FL treatment were excluded from the analysis of prognostic factors.

A median of 3 treatment cycles were given in SL therapy (range: 1–15).

Overall survival (OS)

Median OS for all 170 patients was 11 months (95% CI: 9.2–12).

Time between end of therapy and death

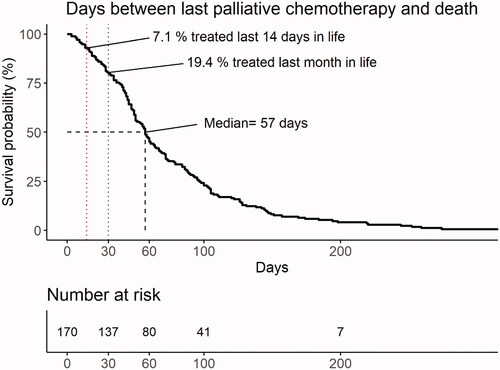

Median time between last date of chemotherapy and death was 57 days (range: 3–340), with seven outliers living ≥200 days (). Chemotherapy was administered during the last month of life in 33 patients (19%) and during the last 14 days of life in 12 patients (7%). There was no difference in age (< 60 years vs. ≥60 years) or gender between patients who did and did not receive chemotherapy within one month before death.

Figure 2. Days between last palliative chemotherapy treatment and death for all patients (n = 170) starting palliative chemotherapy. Median time between last treatment and death was 57 days. In all, 19% of patients were treated with cytostatic drugs during the last month of life, with 7% receiving such treatment in the last 14 days of life.

Survival following SL treatment

Median OS from start of SL treatment was 5.0 months (95% CI: 4.0–6.1). Patients with locally advanced disease lived significantly longer than those with metastatic disease, with OS of 9.6 months (range: 2.9–20.2) and 4.8 months (95% CI: 3.4–7.3), respectively (p = .03). Number of metastatic sites did not affect OS; those with 1 location had a median OS of 4.6 months (95% CI: 3.6–7.3) while those with >1 location had a median OS of 4.9 months (95%: CI 3.4–6.1). Patients with metastatic disease who did not receive SL therapy had a median OS of 1.8 months (95% CI: 1.5–2.6), compared to 6.2 months (95% CI: 4.9–8.8) in patients with metastatic disease who received monotherapy in SL.

Association between patient-specific data and survival

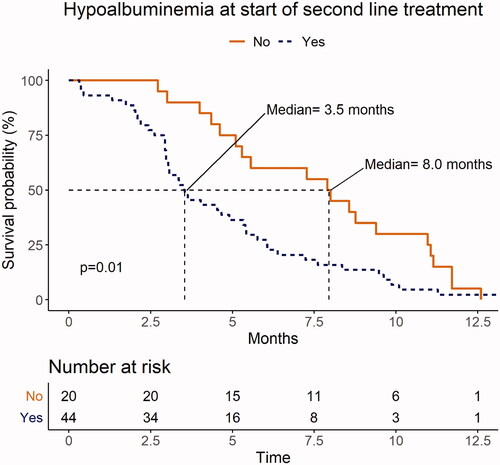

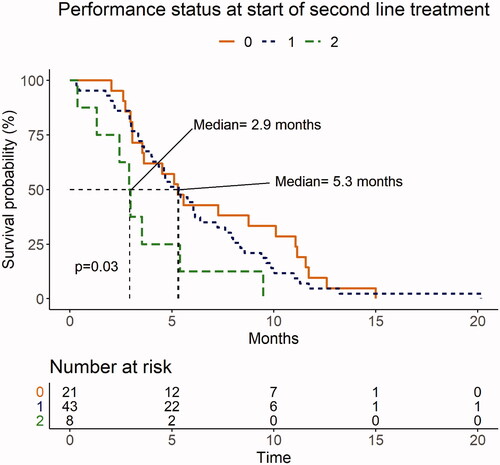

Univariate analysis showed that patients with hypoalbuminemia at the start of SL therapy had a median OS of 3.5 months (95% CI: 3.0–5.4), compared with 8.0 months (95% CI: 5.3–11.1) for patients with normal albumin levels (p = .009; ). Median OS for patients with PS 2 (n = 8) before the start of SL therapy was 2.9 months (range: 0.4–9.5) months compared to 5.3 months for patients with PS 0 (95% CI: 3.5–11.1) and PS 1 (95% CI: 4.0–7.6) (p = .03; ).

Figure 3. Presence and absence of hypoalbuminemia (<36 g/L) at the start of second-line palliative chemotherapy. Albumin values were missing in 8 of the 72 patients. Of the 64 available values, 44 (69%) were <36 g/L. Median overall survival (OS) for patients after progression on first-line treatment (FL) was 3.5 months for those with hypoalbuminemia versus 8.0 months for patients with normal albumin levels (p = .01).

Figure 4. Performance status (PS) before the start of second-line (SL) palliative chemotherapy after progression on first-line (FL) treatment. Of the 72 patients who started SL treatment, 21 (29%) had PS 0, 43 (60%) had PS 1, and 8 (11%) had PS 2. Median overall survival (OS) for patients with PS 0–1 was 5.3 months versus 2.9 months for patients with PS 2 (p = .03).

No association was found between length of PFS following FL therapy and the median OS on SL treatment.

Weight loss during FL therapy was not significantly associated with OS, as patients with weight loss of <5%, 5–<10% and ≥10% had median survival times of 5.5, 5.3, and 4.0 months, respectively (p = .5). There was also no association between survival and the presence or absence of doubling of CA 19-9 after FL therapy; median OS was 6.6 months among patients with doubling and 3.6 months among patients without (p = .4).

Discussion

In patients with pancreatic cancer where a dismal prognosis is at hand, it is a challenge to identify those who may or may not benefit from second-line palliative chemotherapy. In this retrospective study, hypoalbuminemia and a poor PS were associated with short survival time, and so patients in this situation are at risk of receiving futile chemotherapy. The benefit of FL palliative chemotherapy is well documented, with median survival of up to one year, alleviation of cancer-related symptoms, and maintained QoL [Citation20]. However, there is no clear consensus among treating physicians today, and it is still debated when and to whom SL palliative chemotherapy could be recommended. Walker et al. proposed that a median OS of 6 months on SL treatment justifies the palliative treatment [Citation13].

We found that hypoalbuminemia at start of SL therapy was a negative prognostic factor for survival, with hypoalbuminemic patients showing a markedly reduced median OS of 3.5 months as compared to 8.0 months among patients with normal albumin levels (≥36 g/L). These results are in line with a 2014 study by Pant et al., who proposed a low baseline albumin (<34 g/L) to be an independent negative prognostic factor in patients with PS 0–1 and reported a median OS (from start of palliative chemotherapy) of 4.9 months in these low-albumin patients compared to 9.6 months in patients with normal albumin [Citation21]. Patients with metastatic disease who did not receive SL treatment had an OS of 1.8 months, while the corresponding figure among patients treated with further lines was 6.2 months. This was not surprising, as patients eligible for SL treatment had better performance status than patients who did not qualify for further tumor-specific therapy.

We found that a performance status of 2 at the start of SL palliative chemotherapy was a poor prognostic factor for survival, with these patients showing a median OS of 2.9 months compared to the 5.3 months among patients with PS 0–1. This in concordance with a previous study among patients undergoing SL palliative treatment, which found a median OS of 5.3 months in patients with PS 0 and 3.4 months in patients with PS 1–2 [Citation22]. The sample size in that study was twice as big (n = 144) as in ours, and the proportion of patients with PS 2 was slightly higher (16% vs. the 11% in our study); moreover, the merging of patients with PS 1 and 2 skews the comparison to our patients with PS 2. A meta-analysis including 335 patients in any stage of pancreatic cancer found that PS 2–4 was the major negative prognostic factor for poor OS. Patients with metastatic disease and poor PS had an OS of 93 days compared to 223 days in patients with PS 0–1 (p < .001) [Citation23].

A long duration of FL therapy, representing a long PFS, could indicate a treatment response while a shorter duration might imply a treatment-resistant tumor. Sinn et al. showed that a longer duration (>4 months) of FL treatment was a positive independent prognostic factor for an increased median OS on SL treatment [Citation18]. However, our results are in concordance with the findings of Bittoni et al., who saw no association between length of PFS and survival on SL therapy [Citation22].

We also found no association between weight loss during FL therapy and poorer prognosis. Our findings are in part supported by a study from 2017, where a weight-loss of ≥5% was not associated with a poorer prognosis compared to a weight-loss <5%, with OS of 9.5 and 12.6 months respectively (p = .4); however, a weight loss above 10% before start of FL therapy had a negative impact on prognosis, with a hazard ratio of 1.77 (1.09–2.87) [Citation24]. One possible reason for the discrepancy is the small size of our study group, with only 19 patients losing more than 10% of their body weight during FL therapy.

We could not confirm our hypothesis that a doubling of CA 19-9 between the start and end of FL therapy would be a negative prognostic factor. In contrast, a recent retrospective study by Gränsmark et al., including 167 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, found that CA 19-9 above the median value was an independent poor prognostic factor for OS on SL treatment, resulting in a HR for death of 2.03 (p = .009) [Citation25]. As we applied different approaches to assessing changes in CA 19-9, our results are not comparable to these.

The goal and expectations of SL palliative chemotherapy must be clearly and carefully discussed with the patient. The oncologist must present a realistic view of possible positive effects of treatment as well as the side-effects. A trustful discussion with the patient and family is important before the decision to initiate palliative therapy. All of this is essential to avoid a situation where tumor-specific therapy is given near the end of life, distorting the focus away from initiating and planning for end-of-life care. Chemotherapy during the last 30 days of life is considered to be futile, with a risk of impaired QoL close to death [Citation26,Citation27].

We found a median OS during SL therapy of 5.0 months (95% CI: 4.0–6.1). In all, 19% of our patients were treated with chemotherapy during the last month of life, with 7% undergoing such treatment in the last 14 days of life. These results are in line with findings from other studies of patients with solid tumors receiving palliative chemotherapy [Citation28,Citation29], and may imply an overuse of chemotherapy. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) states that the use of chemotherapy in patients when there is no evidence of clinical value is widespread, wasteful, and an unnecessary practice in oncology [Citation30].

However, ASCO also states that treatment for metastatic cancer can be recommended even without an improvement in survival as long as it improves the patient’s QoL [Citation31]. Due to the retrospective design of this study, no QoL data could be recorded, and to our knowledge there are no studies on the impact of QoL in SL palliative therapy in pancreatic cancer patients. Previous studies have reported a decreased QoL associated with futile palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life, with emergency ward visits, hospitalizations, and fewer patients dying in their preferred place, and thus with risk of impaired end-of-life care [Citation19,Citation27].

The problem of estimating life expectancy in incurably ill cancer patients is well-known, and often both the treating physician and the patient overestimate the patient’s remaining time in life [Citation28,Citation32]. There is a need for improvement in selection of patients with pancreatic cancer who are eligible for tumor-specific treatment after progression on FL treatment. When discussing further lines of palliative chemotherapy, the patient and their family are entitled to information that is as truthful as possible regarding gain in survival, prognosis, and symptom control. It is therefore warranted to critically consider potential gain in survival and/or QoL before initiating SL chemotherapy in a patient with pancreatic cancer. The results in our study suggest that hypoalbuminemia and PS 2 are negative prognostic factors.

Limitations

The main weakness of this study is the retrospective setting, with no evaluation of QoL. There was heterogeneity in the selection of patients starting SL treatment, as 18 patients received FL therapy with an adjuvant intention but became qualified for SL treatment due to progression during this FL treatment. The consequence of this is the high number of patients receiving monotherapy with gemcitabine as FL palliative chemotherapy. Multivariate analysis was not performed due to limited sample size and heterogeneity of the study sample.

Conclusions

This retrospective study found that poor performance status (PS 2) and hypoalbuminemia were negative prognostic factors for survival on SL palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Short length of PFS, doubled CA 19-9, and weight loss following FL therapy did not negatively affect median OS following SL therapy in this sample.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ASCO | = | American Society of Clinical Oncology |

| CT | = | Computed tomography |

| ESMO | = | European Society of Medical Oncology |

| FL | = | First-line |

| FLOX | = | 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and leucovorin |

| FOLFIRINOX | = | Oxaliplatin, irinotecan, leucovorin and fluorouracil |

| Nab-Paclitaxel | = | Albumin bound paclitaxel |

| OFF | = | 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin and leucovorin |

| OS | = | Overall survival |

| PFS | = | Progression-free survival |

| PS | = | Performance status |

| QoL | = | Quality of life |

| SL | = | Second-line |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.7 KB)Acknowledgments

The statistical analysis was performed in collaboration with Clinical Studies Sweden – Forum South and statistician Andrea Dahl Sturedahl.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Cancer Observatory [Internet]. Sweden. 2018; [cited 2021 Aug 26]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/752-sweden-fact-sheets.pdf.

- Carrato A, Falcone A, Ducreux M, et al. A systematic review of the burden of pancreatic cancer in Europe: real-world impact on survival, quality of life and costs. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46(3):201–211.

- Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al. ESPAC-4: a multicenter, international, open-label randomized controlled phase III trial of adjuvant combination chemotherapy of gemcitabine (GEM) and capecitabine (CAP) versus monotherapy gemcitabine in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: five year follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15_suppl):4516–4516.

- Thibodeau S, Voutsadakis I. FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of retrospective and phase II studies. J Clin Med. 2018;7:7.

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825.

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703.

- Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(27):JCO2001364–3230.

- Ryan DP. Chemotherapy for advanced exocrine pancreatic cancer. UpToDate [internet]. 2021; [Jun 30. cited 2021 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-systemic-chemotherapy-for-metastatic-exocrine-pancreatic-cancer.

- Wang-Gillam A, Hubner RA, Siveke JT, et al. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:78–87.

- Ioka T, Komatsu Y, Mizuno N, et al. Randomised phase II trial of irinotecan plus S-1 in patients with gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116(4):464–471.

- Portal A, Pernot S, Tougeron D, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after Folfirinox failure: an AGEO prospective multicentre cohort. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(7):989–995.

- Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, et al. Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (off) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(11):1676–1681.

- Walker E, Ko A. Beyond first-line chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer: an expanding array of therapeutic options? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(9):2224–2236.

- Sonbol MB, Firwana B, Wang Z, et al. Second-line treatment in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2017;123(23):4680–4686.

- Gill S, Ko Y-J, Cripps C, et al. PANCREOX: a randomized phase III study of fluorouracil/leucovorin with or without oxaliplatin for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer in patients who have received gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(32):3914–3920.

- Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(23):2423–2429.

- Dadi N, Stanley M, Shahda S, et al. Impact of Nab-Paclitaxel-based second-line chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(10):5533–5539.

- Sinn M, Dälken L, Striefler JK, et al. Second-line treatment in pancreatic cancer patients: who profits?—results from the CONKO study group. Pancreas. 2016;45(4):601–605.

- Bao Y, Maciejewski RC, Garrido MM, et al. Chemotherapy use, end-of-life care, and costs of care among patients diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(4):1113–1121.e3.

- Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F, et al. Impact of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(1):23–29.

- Pant S, Martin LK, Geyer S, et al. Baseline serum albumin is a predictive biomarker for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with bevacizumab: a pooled analysis of 7 prospective trials of gemcitabine-based therapy with or without bevacizumab. Cancer. 2014;120(12):1780–1786.

- Bittoni A, Pellei C, Lanese A, et al. Prognostic factors in advanced pancreatic cancer patients receiving second-line chemotherapy: a single institution experience. Transl Cancer Res. 2018;7(5):1190–1198.

- Tas F, Sen F, Odabas H, et al. Performance status of patients is the major prognostic factor at all stages of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18(5):839–846.

- Nemer L, Krishna SG, Shah ZK, et al. Predictors of pancreatic cancer-associated weight loss and nutritional interventions. Pancreas. 2017;46(9):1152–1157.

- Gränsmark E, Bågenholm Bylin N, Blomstrand H, et al. Real world evidence on second-line palliative chemotherapy in advanced pancreatic cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1176.

- Näppä U, Lindqvist O, Rasmussen BH, et al. Palliative chemotherapy during the last month of life. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(11):2375–2380.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Keating NL, et al. Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1219.

- Harrington SE, Smith TJ. The role of chemotherapy at the end of life: “when is enough, enough?” JAMA. 2008;299(22):2667–2678.

- Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(4):394–400.

- Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, et al. American society of clinical oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: the top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1715–1724.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Outcomes of cancer treatment for technology assessment and cancer treatment guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(2):671–679.

- Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, et al. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(2):79–86.