Abstract

Background

Squamous cell cancer of the anus is an uncommon malignancy, usually caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). Chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is the recommended treatment in localized disease with cure rates of 60–80%. Local failures should be considered for salvage surgery. With the purpose of improving and equalizing the anal cancer care in Sweden, a number of actions were taken between 2015 and 2017. The aim of this study was to describe the implementation of guidelines and organizational changes and to present early results from the first 5 years of the Swedish anal cancer registry (SACR).

Methods

The following were implemented: (1) the first national care program with treatment guidelines, (2) standardized care process, (3) centralization of CRT to four centers and salvage surgery to two centers, (4) weekly national multidisciplinary team meetings where all new cases are discussed, (5) the Swedish anal cancer registry (SACR) was started in 2015.

Results

The SACR included 912 patients with a diagnosis of anal cancer from 2015 to 2019, reaching a national coverage of 95%. We could show that guidelines issued in 2017 regarding staging procedures and radiotherapy dose modifications were rapidly implemented. At baseline 52% of patients had lymph node metastases and 9% had distant metastases. Out of all patients in the SACR 89% were treated with curative intent, most of them with CRT, after which 92% achieved a local complete remission and the estimated overall 3-year survival was 85%.

Conclusions

This is the first report from the SACR, demonstrating rapid nation-wide implementation of guidelines and apparently good treatment outcome in patients with anal cancer in Sweden. The SACR will hopefully be a valuable source for future research.

Keywords:

Background

Squamous cell anal carcinoma (anal cancer) is an uncommon malignancy, but the incidence is increasing in many Western countries. The majority of anal cancers are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV). The therapeutic mainstay in localized disease is radiotherapy (RT) combined with chemotherapy, that is chemoradiotherapy (CRT) [Citation1] with cure rates of 60–80% [Citation2]. Local failure occurs in 15–25% of patients, for whom salvage surgery should be considered. Late morbidity is common among survivors after CRT [Citation3]. Thus, even though standard CRT is a rather effective treatment, further improvements are needed. Distant metastases, occurring in approximately 20% of patients either at diagnosis or during follow-up are associated with a poor prognosis.

In 2010, a national cancer policy plan was launched in Sweden. Standardized national care programs and national cancer registries, already existing for common cancer diagnoses, were to be implemented for all cancer forms. In addition, for some rare malignancies, treatments were centralized to fewer centers and national multidisciplinary team meetings were formed. These strategies have been gradually introduced nationwide for different cancers during the past decade.

Prior to 2015, patients with anal cancer were treated with CRT at 10 different oncology departments in Sweden and salvage surgery was performed at most rectal cancer units across the country. National guidelines and coordination were largely lacking. Given the rarity of the disease, with slightly more than 100 patients receiving CRT and approximately 20 cases of salvage surgery every year, a number of actions were taken from 2015 and onwards to improve and equalize the anal cancer care in Sweden.

The aim of this study was to describe the implementation of new guidelines and organizational changes. Also, early results from the first five years (2015–2019) of the Swedish anal cancer registry (SACR), including 912 consecutive patients, are presented.

Methods

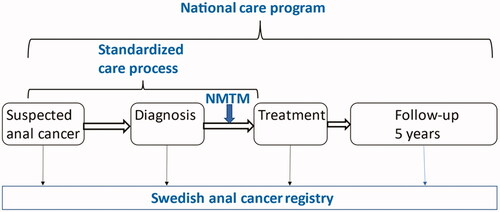

The actions taken can be categorized into three main groups; guidelines, organization and registration (). The guidelines consist of the national care program and the standardized care process, with recommendations on how patients with anal cancer should be managed. They also include specific goals that should be achieved. Organizational changes – centralized care and national multidisciplinary team meetings – were performed to facilitate achieving the goals defined in the guidelines. The SACR was initiated to monitor treatment outcome as well as the effects of the actions taken. This study was approved by the Swedish ethical review authority (Dnr 2020-06085).

Figure 1. Overview of the management of patients with anal cancer in Sweden, with organizational changes implemented 2015-2017 (in blue). NMTM, national multidisciplinary team meeting.

National care program

The first national care program for anal cancer, launched in 2017, contains recommendations on workup, treatment and follow-up, based on current evidence. A biopsy showing squamous cell carcinoma, or high grade anal intralesional neoplasia combined with a clinical or radiological cancer, is mandatory. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 (a surrogate marker for HPV) is recommended, as well as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis and a [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET-CT) at baseline. All new cases should be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting. For localized anal cancer the national care program defines different CRT schedules for early and locally advanced tumors, using simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) or shrinking field techniques [https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/analcancer/vardprogram/]. In the SIB schedule for early tumors, patients with T1-2 (<4cm) N0 M0 are treated with 54 Gy to the primary tumor and 41.6 Gy to elective lymph nodes in 27 fractions concurrent with one cycle of mitomycin C combined with 5-fluorouracil (FUMI) or capecitabine (CapMI). Locally advanced tumors, T2 (≥4cm)-T4 or N + and M0 typically receive 57.5 Gy to the primary tumor, 50.5 Gy to lymph node metastases and 41.6 Gy to elective lymph nodes in 27 fractions, combined with two cycles of FUMI or CapMI. RT is always planned without a break, five fractions per week. These schedules implied reductions of RT doses and adaptation to several international guidelines, compared to previous Nordic and local guidelines, where lymph node metastases usually received 58–60 Gy and elective lymph nodes 46 Gy [Citation2]. For small perianal tumors a local excision may suffice, but postoperative CRT is often recommended, especially in case of unclear margins. Response evaluation after primary CRT is performed at 3-6 months after the end of treatment. In case of locally advanced cancer a post-treatment MRI or a PET-CT is recommended. Residual tumors and local recurrences should be considered for salvage surgery.

In the national care program, a number of goals were set for the anal cancer care in Sweden. Some of these were elucidated in the current study: (1) 100% registration rate in the SACR, (2) Addition of chemotherapy to RT in >90% of cases where treatment is planned with curative intent, (3) >70% overall 5-year survival in patients treated with curative intent.

Standardized care process

A standardized care process for anal cancer was implemented in 2017, with the main purpose of shortening the lead times from symptom to start of treatment, which in turn could improve the prognosis and reduce the patients’ somatic as well as psychological distress caused by prolonged periods of suspense. Specific findings associated with a high suspicion of anal cancer have been defined, e.g. a “clinically malignant” lesion or a lesion that was initially deemed benign that has not improved after four weeks of treatment. The time period from when a highly suspicious anal cancer is recognized, at any health care unit, until start of anal cancer treatment, usually CRT, should not exceed 47 days, during which clinical examination, ano-rectoscopy, tumor biopsy, MRI, PET-CT and discussion at the national multidisciplinary team meeting should be performed.

Centralized care

Due to the low incidence of the disease and the complexity of the treatment, a centralization of anal cancer treatment was recommended in 2016. It was decided that curative CRT should be given at four oncology departments (Umeå, Uppsala, Gothenburg and Lund) and salvage surgery at two surgical units (Gothenburg and Malmö). This was gradually implemented between 2017 and 2019.

National multidisciplinary team meetings

National multidisciplinary team meetings for anal cancer were initiated in 2017, where all new cases in Sweden are presented. Local failures are also discussed, especially when salvage surgery is potentially possible. These meetings take place digitally once a week, with representatives from all anal cancer centers in Sweden. Participating experts include oncologists, surgeons, radiologists and specialized nurses. Baseline MRI and PET-CT investigations are reviewed by a radiologist for TNM staging, and treatment recommendations are provided.

Swedish anal cancer registry (SACR)

SACR was launched in 2015. It consists of different modules, content in brief:

Baseline: WHO performance status, radiology, histopathology, p16 staining, and TNM stage. In this study the 7th edition (AJCC 2010) was used, where T1 indicates primary tumor ≤2 cm, T2: >2–5 cm, T3: >5 cm, T4: invasion into adjacent organs N1: perirectal, N2: unilateral internal iliac or inguinal, N3: perirectal and inguinal, or bilateral internal iliac, or bilateral inguinal lymph node metastases, M1: distant metastases.

Treatment: Surgery (resections of anal tumor or metastases, deviating stoma, and surgery due to treatment complications), radiotherapy (dosing and targets), and chemotherapy (both concurrent with RT and for metastatic disease).

Response evaluation: 3–6 months after completion of CRT.

Follow-up: Yearly for 5 years. Late side-effects (RTOG late radiation toxicity score), recurrences, and treatment of recurrences are documented.

Statistics

Data are mainly presented by descriptive statistics. Overall survival (OS) was analyzed with Kaplan-Meier estimates and log-rank test. Multivariable analyses for factors influencing OS (gender, age, TNM stage, p16 status, and treatment intention) were performed using Cox regression. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.3 and p <.05 was considered statistically significant [Citation4].

Results

Incidence and registry completeness

The anal cancer incidence in Sweden has risen sharply during the past 50 years, especially in the last decade. In the early 1970s, approximately 50 new patients were diagnosed with anal cancer per year, compared to more than 200 yearly cases today. The coverage of the SACR baseline registration form, in relation to the total number of cases according to the Swedish Cancer Registry, increased from 56% in 2015 to 95% in 2019. The coverage of registration of primary oncological treatment was approximately 95%, whereas the registration of response evaluation after curative CRT was done in 81%.

Baseline characteristics

As of 1st of April 2021, 912 patients had been registered in the SACR, diagnosed with anal cancer between 2015 and 2019. The median age was 68 years and 76% were females (). WHO performance status was 0–1 in 76% of cases. A majority of tumors (85%) involved the anal canal. In 11% of cases the tumor was entirely located in the anal margin. The distal rectum was involved in 25% of cases and in 3% of patients the tumor was solely located in the rectum without growth in the anal canal. Lymph node metastases (N1-3) were present in 52% of patients and 9% had distant metastases (M1) at diagnosis, most frequently in the liver followed by extrapelvic lymph nodes and lung. Positive staining for p16 in the tumor was observed in 90% of patients, 95% among women and 77% among men. The proportion of patients receiving a pretreatment stoma was 14%.

Table 1. Patient and tumor characteristics.

Primary treatment

The majority of patients (89%), for whom the treatment intention was reported, were planned for primary treatment with curative intent (). Primary surgical resection was performed in 93 (10%) patients, mainly local excisions, which in 73% of cases was followed by postoperative RT. Most patients (n = 639) received primary RT with curative intent, including concomitant chemotherapy in 93% of cases, to a median RT dose of 58 Gy. The median overall RT treatment time was 39 days (interquartile range: 37–43 days), and the treatment was delayed by >3 days in 10% of patients. Among patients receiving RT with curative intent, 26% had a hospital admission due to treatment-related side effects.

Table 2. Primary treatment.

Regarding the choice of concomitant chemotherapy regimen, mitomycin C was most frequently used, combined with 5-fluorouracil (63%) or capecitabine (30%). It should be noted that summarizes treatment of all patients in the SACR, thus including patients treated both before and after implementation of the national care program.

Response evaluation

In patients undergoing RT with curative intent, a response evaluation was performed at a median time of 4.4 months after completion of RT. Most patients were reevaluated with CT-PET (77%), whereas MRI was done in 25% and both CT-PET and MRI in 21% of cases (). In 20% no radiological examination was done. A post-treatment biopsy was performed in 13%. The local complete response rate was 92% (96% in women and 81% in men). Distant metastases were detected at response evaluation in 5% of cases.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate predictors for overall survival.

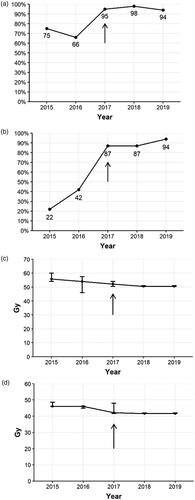

Compliance with guidelines

The guidelines were launched and the organizational changes were performed in 2017. Accordingly, some of the effects of these changes can be monitored by SACR, covering the time period from 2015 to 2019. Ninety per cent of patients were discussed at multidisciplinary team meetings. The proportion of patients undergoing baseline investigations with both MRI and PET-CT increased to 95% after 2017 (). The proportion of p16-stained cases raised sharply to approximately 90% in 2017 and onwards (). The median lead time from diagnosis to start of treatment decreased marginally to slightly below 50 days. Regarding the modified RT doses implemented in 2017, the median dose to lymph node metastases decreased from 55.8 Gy to 50.5 Gy between 2015 and 2019 (), and the median RT doses to elective lymph nodes were reduced from 46 Gy to 41.6 Gy (). The interpatient variations in RT doses, depicted as interquartile ranges, decreased during the observation period, indicating improved equality in RT dosing across the country.

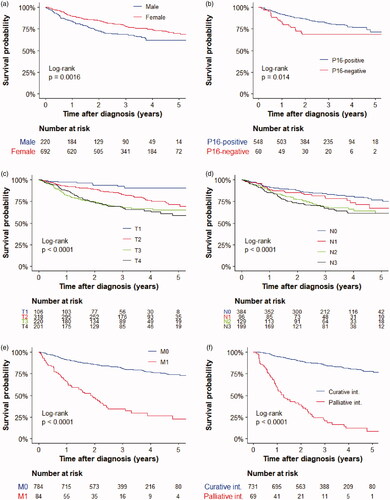

Survival

The median follow-up time for patients alive at data extraction was 40 months (interquartile range: 29–53 months). OS was significantly longer among women than men (), in patients with p16-positive tumors (), and in patients with lower TNM stages (). The estimated OS at 3 years for patients treated with curative intent was 85% (). In the multivariable analyses, male gender, older age, non-curative treatment intention, and advanced stages were significantly associated with worse OS, whereas p16 status was not ().

Discussion

This is the first report from the Swedish Anal Cancer Registry (SACR) that has been operating since 2015. Anal cancer is an uncommon malignancy with approximately 200 new cases yearly in Sweden, but owing to a high inclusion rate in the SACR, the first 5-year cohort presented here contains more than 900 prospectively registered patients, which makes it a comparatively large material of patients with anal cancer.

A number of actions were initiated in 2015 with the purpose of equalizing and improving the management of anal cancer in Sweden. National guidelines were launched in 2017, including that MRI, PET-CT, and p16 staining should be done at baseline, that patients should be discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting, and that the RT doses to involved and elective lymph nodes should be lowered. For all of these items a clear improvement is noted between 2016 and 2017 (). It seems reasonable to assume that the rapid implementation of these recommendations was facilitated by concurrent organizational actions. With a centralization of anal cancer treatment to four hospitals in Sweden and with weekly national multidisciplinary team meetings, the routes of communication are very short and efficient.

According to our standardized care process, the lead time from recognition of ‘high suspicion of anal cancer’ until start of treatment should not exceed 47 days. This variable can still not be reliably evaluated from the registry, but as a reasonable surrogate marker we found that the median time from diagnosis to start of CRT was around 50 days, with only slight improvement during the study period. This suggests that the lead time goal has not yet been fulfilled. Whether this affects the oncological outcome is unclear. The main goal with the standardized care processes is to shorten the lead time from symptoms to start of treatment and thereby reducing unnecessary wait and hopefully also improving the prognosis. In head and neck cancer, recent studies have shown that prolonged time from diagnosis to surgery [Citation5] and from surgery to postoperative RT [Citation6] is associated with worse prognosis. However, for anal cancer the relations between lead times and prognosis are incompletely known. The time limit of 47 days to start of CRT was based on logistic and practical considerations rather than scientific evidence. More studies are needed on the impact of lead times in anal cancer.

The first five years of the SACR consists of 912 patients diagnosed between 2015 and 2019. Given the high registration level, with 95% coverage during the last years, this gives a representative picture of the real-world panorama of this disease. Regarding tumor staging it could be noted that 52% of patients had N + disease (). That is higher than in a previous Nordic study [Citation2] from 2000-2007, where 30% had lymph node positivity. This reflects a stage migration that was subjected to a systematic review by Sekhar et al. [Citation7], mainly caused by the use of more sensitive imaging techniques during the last decades. By meta-regressions they simulated that the ‘true’ proportion N + in an unselected population of anal cancers is probably not over 30%. If this is correct it indicates an overstaging with MRI and/or PET-CT, showing the need for further studies and guidelines on how to interpret lymph node status with those two imaging techniques [Citation8]. A similar stage migration was noted for the M stage, where less than 5% were reported to have distant metastases at diagnosis in series from the 90 s and early 00 s [Citation2,Citation9], compared to 9% in the present study (), most likely due to intensified baseline imaging.

Fourteen per cent of the patients had a pretreatment deviating stoma, which is well in line with previous reports [Citation1,Citation10]. A majority of patients received RT with curative intent (), to a median RT dose of 58 Gy, 93% of them had concomitant chemotherapy, and only 10% had a treatment delay of more than 3 days. This reflects the ambition to give CRT whenever possible and recognizing the negative prognostic impact of a prolonged overall treatment time [Citation11]. However, the high treatment intensity comes at the prize of acute side effects, with 26% of patients being admitted to the hospital due to treatment-related toxicity (). More detailed analyses on different treatment strategies, stratified by stage and clinical situation, will follow in subsequent publications based on this registry.

After CRT the treatment response needs to be determined. Results from the ACT II trial showed that it may take up to 6 months after start of CRT to establish a complete response[Citation12]. In the current study the median time from the end of curative RT until response evaluation was 4.4 months, which means that in almost half of our patients the final response evaluation was performed later than 6 months after starting RT, emphasizing that some patients with anal cancer are indeed slow responders. In addition to clinical examination a post-treatment PET-CT was performed in 77% and MRI in 25% of cases. The local compete response rate was 92% which is well in line with the best results from randomized trials [Citation10,Citation13]. There is no international consensus on optimal imaging for response evaluation. In both PET-CT [Citation14] and MRI [Citation15], normalization of malignant features is associated with improved tumor control, whereas their ability to predict local failure needs to be improved. In the post-treatment PET-CT, new distant metastases were found in 5% of patients. Early detection of oligometastases is important since these may be amenable for curative interventions. Further research on the value of different post-treatment imaging is needed [Citation8].

The OS in patients treated with curative intent was 85% at 3 years (), similar to randomized trials [Citation12,Citation13,Citation16] and previous registry studies [Citation2,Citation9], Stratifying the cohort by M-stage showed that the OS, unsurprisingly, was much better in patients with localized disease compared to them with synchronous metastases (). In the M1 group, the median and 3-year OS was 22 months and 26%, respectively, which is in the same order of magnitude as in a recent Norwegian registry study [Citation9]. It should be noted that these are crude data, not taking treatments into account, but even so our results indicate that there is a subset of long-term survivors also with M1 disease. Previous retrospective studies have shown that some patients benefit from active local treatment of oligometasteses, using CRT [Citation17] and local resection or other ablative techniques [Citation18]. Further studies of M1 patients in the SACR with analyses of treatment strategies for different metastatic sites, will follow.

It is well known that patients with HPV positive anal cancer have a better prognosis than those with HPV-negative tumors [Citation19] and that immunohistochemical staining for p16 is a good surrogate marker for HPV. The inferior OS associated with p16 negative disease was confirmed in the present study (in univariate analysis), as well as a worse prognosis for male patients, in accordance with several previous reports [Citation2,Citation9] (). We also found a clear gender difference in p16 status, with p16-positivity in 95% of the women but only in 77% of the men, which possibly contributes to the gender difference in prognosis. However, in the multivariable analysis (), male gender remained a significant factor for worse OS after adjustment for p16 status and TNM stage, suggesting that there are additional explanations for the inferior outcome in men with anal cancer. Further research is needed.

The current study was based on the newly initiated SACR. A limitation with all quality registries, that are integrated parts of the health care system, is the risk of data entry errors and missing values. There is no routine monitoring of all data entered. In the current study, missing values were noted in up to 10% of cases in some of the variables. The Swedish colorectal cancer registry which opened in 1995, has been subjected to several validation studies where the latest of them [Citation20] showed an average agreement of 90% between registry data and source data retrieved from medical records. Similar validation studies should be performed also of SACR. As for clinical outcomes we present data on response after primary RT and OS. Other clinically important endpoints include tumor recurrences, both locoregional and distant, but these have not yet been analyzed. Another limitation was the relatively short median follow-up time of 40 months, but since most recurrences occur within three years, this should not have a major impact on our results.

Conclusions

With the aim of improving and equalizing the anal cancer care in Sweden, a number of national-level actions were undertaken between 2015 and 2017. In the present paper, we show that new guidelines were rapidly implemented across the country. Clinical features, treatment and outcomes for the first 5-year cohort from the SACR, comprising 912 patients, are presented. A high local complete response rate of 92% was observed after RT with curative intent. The SACR will hopefully be a valuable source for future research projects.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the staff members who keep the registry up to date and to Barbro Numan for statistical assistance. This work was supported financially by Skåne County Council, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data, derived from the Swedish anal cancer registry, are not publicly available for legal and ethical reasons, since they contain information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants. However, data supporting some of the findings in the study are publicly available in an interactive report (in Swedish) that is updated yearly (https://cancercentrum.se/samverkan/cancerdiagnoser/tjocktarm-andtarm-och-anal/anal/kvalitetsregister).

Further data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [AJ] upon reasonable request.

References

- Rao S, Guren MG, Khan K, et al. Anal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up⋆. Ann Oncol. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: [email protected] 2021;32(9):1087–1100.

- Leon O, Guren M, Hagberg O, et al. Anal carcinoma - Survival and recurrence in a large cohort of patients treated according to nordic guidelines. Radiother Oncol. 2014;13(3):352–358.

- Bentzen AG, Balteskard L, Wanderås EH, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life after chemoradiotherapy for anal cancer: late effects in a national cohort of 128 survivors. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden). 2013;52(4):736–744.

- R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. URL. https://www.R-project.org/.2020.

- Rygalski CJ, Zhao S, Eskander A, et al. Time to surgery and survival in head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(2):877–885.

- Harris JP, Chen MM, Orosco RK, et al. Association of survival with shorter time to radiation therapy after surgery for US patients with head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(4):349–359.

- Sekhar H, Zwahlen M, Trelle S, et al. Nodal stage migration and prognosis in anal cancer: a systematic review, Meta-regression, and simulation study. The Lancet Oncology. 2017; 18(10):1348–1359.

- Guren MG, Sebag-Montefiore D, Franco P, et al. Treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus, unresolved areas and future perspectives for research: Perspectives of research needs in anal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2021;20(4):279–287.

- Guren MG, Aagnes B, Nygård M, et al. Rising incidence and improved survival of anal squamous cell carcinoma in Norway, 1987-2016. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2019;18(1):e96–e103.

- James RD, Glynne-Jones R, Meadows HM, et al. Mitomycin or cisplatin chemoradiation with or without maintenance chemotherapy for treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, 2 x 2 factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):516–524.

- Graf R, Wust P, Hildebrandt B, et al. Impact of overall treatment time on local control of anal cancer treated with radiochemotherapy. Oncology. 2003;65(1):14–22.

- Glynne-Jones R, Sebag-Montefiore D, Meadows HM, et al. Best time to assess complete clinical response after chemoradiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the anus (ACT II): a post-hoc analysis of randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. ACT II study group 2017;18(3):347–356.

- Peiffert D, Tournier-Rangeard L, Gerard JP, et al. Induction chemotherapy and dose intensification of the radiation boost in locally advanced anal canal carcinoma: final analysis of the randomized UNICANCER ACCORD 03 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(16):1941–1948.

- Jones M, Hruby G, Solomon M, et al. The role of FDG-PET in the initial staging and response assessment of anal cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(11):3574–3581.

- Kochhar R, Renehan AG, Mullan D, et al. The assessment of local response using magnetic resonance imaging at 3- and 6-month post chemoradiotherapy in patients with anal cancer. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(2):607–617.

- Ajani JA, Winter KA, Gunderson LL, et al. Fluorouracil, mitomycin, and radiotherapy vs fluorouracil, cisplatin, and radiotherapy for carcinoma of the anal canal: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1914–1921.

- Holliday EB, Lester SC, Harmsen WS, et al. Extended-Field chemoradiation therapy for definitive treatment of anal canal squamous cell carcinoma involving the Para-Aortic lymph nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102(1):102–108.

- Eng C, Chang GJ, You YN, et al. The role of systemic chemotherapy and multidisciplinary management in improving the overall survival of patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Oncotarget. 2014;5(22):11133–11142.

- Serup-Hansen E, Linnemann D, Skovrider-Ruminski W, et al. Human papillomavirus genotyping and p16 expression as prognostic factors for patients with american joint committee on cancer stages I to III carcinoma of the anal canal. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(17):1812–1817.

- Moberger P, Sköldberg F, Birgisson H. Evaluation of the swedish colorectal cancer registry: an overview of completeness, timeliness, comparability and validity. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(12):1611–1621.