Introduction

Periampullary cancer comprises four malignancies arising at close proximity to the ampulla of Vater: ampullary cancer, duodenal adenocarcinoma, distal cholangiocarcinoma, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [Citation1,Citation2]. Together, they make up approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. For all entities, resection of the primary tumor is the only curative option [Citation1,Citation3]. However, the role of (neo)adjuvant and palliative chemotherapy differs per tumor origin [Citation1,Citation3].

The Dutch pancreatic cancer guideline (2019) recommends all (borderline) resectable patients to be treated with adjuvant therapy, in which (modified) FOLFIRINOX is preferred over gemcitabine plus capecitabine [Citation4,Citation5]. In borderline resectable disease, neoadjuvant strategies will be implemented in the updated Dutch guideline (publication in 2022). Patients with locally advanced disease or with metastatic disease and a good performance status are counseled for palliative treatment with FOLFIRINOX. For patients with metastatic disease, older age, or poorer performance status gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel are the alternative. For patients diagnosed with distal cholangiocarcinoma, there is no role for neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy according to the Dutch and European guidelines for biliary tract cancer [Citation6,Citation7]. However, the American Society of Clinical Oncology and National Comprehensive Cancer Network do recommend adjuvant chemotherapy (fluoropyrimidine or gemcitabine-based) [Citation8,Citation9]. The recommendation for gemcitabine plus cisplatin in palliative setting is similar in the consulted international guidelines.

For patients diagnosed with ampullary cancer and duodenal adenocarcinoma, no guidelines are available and high-level evidence on the benefit of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy is lacking. As a consequence, great variations in chemotherapy regimens are expected as physicians might consult various guidelines for adjacent organs (i.e., pancreas, biliary tract, and colon).

A previous study among periampullary cancer patients reported the proportion of patients treated with chemotherapy in adjuvant or palliative setting in general, without providing detailed information on specific chemotherapeutic agents [Citation10]. Therefore, the aim of this short report is to investigate the adjuvant and palliative chemotherapy regimens administered to periampullary cancer patients diagnosed between 2015 and 2019 in the Netherlands, per tumor origin.

Material and methods

Patient selection

For this retrospective cohort study, all patients aged 18 years and older, diagnosed with invasive periampullary cancer (Internal Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3): C17.0, C24.1, C24.2, and C25.0; Supplementary Table 1) between 2015 and 2019 in the Netherlands, and whom were treated with adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy, were selected from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR) [Citation11]. In total, 161 patients were excluded as they received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, without receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. In the Netherlands, neoadjuvant therapy has, until recently, only been administered to pancreatic cancer patients who were enrolled in clinical trials. An additional 20 patients were excluded as the type of chemotherapy regimen was not reported.

The NCR includes all patients with a newly diagnosed malignancy in the Netherlands, identified by (1) the national pathological archive and (2) the National Registry of Hospital Discharge Diagnosis. Trained administrators collect the data from patients medical records up to approximately nine months after diagnosis.

Definitions

The tumor origin (ICD-O-3 classification) was based on the pathological report available after resection or diagnostic biopsy, and – if not available – on imaging and consensus at multidisciplinary meetings. Tumor stage was classified according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM classification edition available at the time of diagnosis: the 7th edition for patients diagnosed until 2016 and the 8th edition from 2017 [Citation12,Citation13]. Tumor classification and lymph node involvement were based on pathological staging of resection specimens. If missing, or when the patient did not undergo surgery, clinical TNM classification (preoperative oncological work-up and/or findings at upfront surgical exploration) was used.

Treatment intent was regarded as ‘adjuvant’ when the patient was diagnosed with TNM stage I-III and underwent resection, and as ‘palliative’ when the patient was diagnosed with TNM stage IV or did not undergo resection disregarding stage.

Endpoints

In this study, the initial chemotherapy, i.e., adjuvant therapy and the first-line palliative therapy, were described. Initial chemotherapy was defined as all agents administered in parallel within the first thirty days of initiation of chemotherapy. Combinations consisting of fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin, and irinotecan, standard or modified, were classified together as FOLFIRINOX. Time until start of chemotherapy was defined as the time from date of resection to the start date of chemotherapy or, if no resection was conducted, the time from date of diagnosis to the start date of chemotherapy. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from date of diagnosis to date of death from any cause or censored at last follow-up date.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to gain insight in the prescribed initial chemotherapies per tumor origin and treatment intent. OS was calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

Patients

Included were 1003 patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy and 1683 patients receiving palliative chemotherapy (). Median age was 66 years (IQR 58−72) and 55% were male. The majority of the tumors were pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (85%), followed by distal cholangiocarcinoma (6%), duodenal adenocarcinoma (6%), and ampullary cancer (3%). The histologic subtype was intestinal in 4% of the patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, pancreatobiliary in 11%, other in 45%, and not further specified in 39%. In the palliative group, 5% were intestinal, 1% pancreatobiliary, 6% other, and 86% not further specified. Of the patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, 14% received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The median time until start of chemotherapy was 56 days (IQR 45−70 d) for patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy and 35 days (IQR 24−56 d) for patients treated with palliative chemotherapy.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Chemotherapy regimens

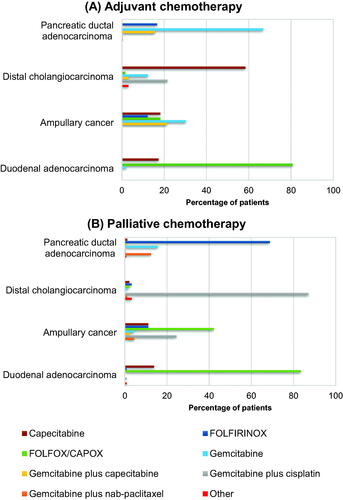

Of the 853 patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, 570 (67%) patients received gemcitabine alone, 142 (17%) FOLFIRINOX, and 133 (16%) gemcitabine plus capecitabine (). In 2018 and 2019, an increase in the proportion of patients treated with FOLFIRINOX was observed (4% in 2015−2017, 20% in 2018, and 53% in 2019) and a decrease in the patients treated with gemcitabine plus capecitabine (83% in 2015−2017, 51% in 2018, and 32% in 2019; Supplementary Figure 1). Among the 1430 patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and treated with palliative chemotherapy, the majority (69%) received FOLFIRINOX (). Gemcitabine alone was administered in 225 (16%) patients and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in 178 (12%).

Figure 1. Chemotherapy regimens prescribed in periampullary cancer patients, per tumor origin (in %). Patients treated with (A) adjuvant and (B) palliative chemotherapy*. FOLFIRINOX: 5-fluorouracil plus irinotecan plus oxaliplatin; FOLFOX/CAPOX: 5-flourouracil or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.*Distal cholangiocarcinoma, adjuvant: 8 = gemcitabine, 2 = gemcitabine plus capecitabine, 1 = capecitabine plus mitomycin, 1 = capectabine plus cisplatin, 1 = FOLFOX/CAPOX; Distal cholangiocarcinoma, palliative: 1 = docetaxel, 1 = gemcitabine, 1 = gemcitabine plus carboplatin, 1 = gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel, 1 = gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin,Duodenal adenocarcinoma, palliative: 1 = FOLFIRINOX, 1 = gemcitabine plus cisplatin, 1 = epirubicin plus oxaliplatin plus capecitabine. Ampullary cancer, palliative: 1 = gemcitabine plus capecitabine, and 2 = gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel.

Among the patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for distal cholangiocarcinoma (n = 65), most frequent administered chemotherapy regimens were capecitabine (n = 38, 58%) and gemcitabine plus cisplatin (n = 14, 22%; ). In the palliative chemotherapy subgroup (n = 93), 81 (87%) patients were treated with gemcitabine plus cisplatin, three (3%) with FOLFIRINOX, two (2%) with FOLFOX/CAPOX, and two (2%) with capecitabine ().

Of the 52 patients diagnosed with duodenal adenocarcinoma, 42 (81%) patients were treated with adjuvant FOLFOX/CAPOX, nine (17%) received adjuvant capecitabine, and only one patient adjuvant gemcitabine (). As palliative chemotherapy, 96 (83%) patients received FOLFOX/CAPOX, and 16 (14%) received capecitabine ().

Of patients with ampullary cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, 10 (30%) patients received gemcitabine alone, seven (21%) gemcitabine plus capecitabine, six (18%) capecitabine alone, six (18%) FOLFOX/CAPOX, and four (12%) FOLFIRINOX (). Of the 45 patients treated with palliative chemotherapy, 19 (42%) were treated with FOLFOX/CAPOX, 11 (24%) with gemcitabine plus cisplatin, five (11%) with FOLFIRINOX, five (11%) with capecitabine, and two (4%) with gemcitabine alone ().

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study is the first to report the contemporary adjuvant and first-line palliative chemotherapy regimens per periampullary tumor origin. For patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, the most frequently administered regimens were gemcitabine and, more recently, FOLFIRINOX for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, capecitabine for distal cholangiocarcinoma, FOLFOX/CAPOX for duodenal adenocarcinoma, and gemcitabine for ampullary cancer. Frequently administered palliative chemotherapies were FOLFIRINOX for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, gemcitabine plus cisplatin for distal cholangiocarcinoma, and FOLFOX/CAPOX for duodenal adenocarcinoma and ampullary cancer.

For patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and distal cholangiocarcinoma, the results are in line with the international and national guidelines [Citation4–8]. Only a limited variation in adjuvant and palliative regimens was seen. Although adjuvant FOLFIRINOX is currently preferred over gemcitabine (plus capecitabine) for pancreatic cancer, gemcitabine alone was more often administered in the first years of the studied timeframe. First, adjuvant gemcitabine was provided in the Netherlands until July 2017 in both arms of the Dutch PREOPANC study investigating the added value of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [Citation14]. Second, the results of the PRODIGE-24 trial, which showed a survival benefit of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX over gemcitabine, were published in 2018 and included in the revised Dutch guideline in 2019 [Citation4,Citation15]. For distal cholangiocarcinoma, the applied adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, capecitabine, and gemcitabine plus cisplatin, are in line with the inclusion of patients in the ACTICCA-1 trial, which started in 2014 in the Netherlands [Citation9].

Nationwide population-based studies among patients diagnosed with duodenal adenocarcinoma reported that 16% of the patients in the Netherlands (2012−2018) and 44% of the patients in the United States of America (USA; 2004−2012) received adjuvant chemotherapy [Citation10,Citation16]. This study showed that patients mainly received FOLFOX/CAPOX as adjuvant and first-line palliative chemotherapy. In the absence of a randomized controlled trial and guidelines, some clinicians apparently treat these patients according to the guidelines for colorectal cancer [Citation17–19]. However, a meta-analysis concluded no difference in the pooled 5-year OS for any type of adjuvant therapy (5-FU based chemo(radio)therapy) compared to observation in patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma [Citation3]. FOLFOX/CAPOX in palliative setting has shown to be associated with an improved survival in a multicenter retrospective study among patients with advanced small bowel cancer, which also included duodenal adenocarcinoma [Citation20]. However, the results may be influenced by treatment selection bias since patients were not randomly assigned to chemotherapy regimens. No studies assessed chemotherapy regimens in advanced duodenal adenocarcinoma separately.

As result of the lack of high-level evidence and guidelines for ampullary cancer, only a small proportion of patients (10%) diagnosed with non-metastatic disease received adjuvant therapy in the Netherlands (2012−2018), and a large variation in adjuvant and palliative chemotherapy regimens was observed in this study [Citation10,Citation16]. The administered regimens are all recommended in available guidelines for cancers in adjacent organs, which confirms that clinicians prefer to consult guidelines over inconclusive studies. Only the ESPAC-3 trial performed a subgroup analysis on the survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy among patients diagnosed with ampullary cancer (n = 304), but adjuvant gemcitabine or 5-FU did not improve OS when compared with observation (HR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.61−1.18; p = .323) [Citation21]. Observational studies on the efficacy of adjuvant therapy in ampullary adenocarcinoma showed inconsistent results [Citation22]. In future studies on chemotherapy regimens, distinction between the histologic subtypes (intestinal vs. pancreatobiliary vs. mixed type) might be needed as the benefit of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy has shown to be different for each subtype [Citation23]. Yet, this study shows that tumors are rarely categorized as intestinal, pancreatobiliary, or mixed subtype, and therefore decisions are expected not to be affected by histology characteristics [Citation24,Citation25].

Of note, a quarter of the patients in this study started adjuvant chemotherapy later than 70 days after resection, which was also observed in previous Dutch studies among pancreatic cancer patients [Citation26,Citation27]. Valle et al. reported that survival was not affected by whether the adjuvant chemotherapy was started < 8 weeks or 8−12 weeks postoperatively [Citation28].

This is the first study to give an overview of the adjuvant and first-line palliative chemotherapy regimens per periampullary tumor origin, reflecting daily clinical practice. However, some limitations of this study should be taken into account. Inherent to the retrospective study design, some data were incomplete or unavailable, e.g., second- and third-line chemotherapy regimens. Therefore, treatment adjustments and trajectories could not be studied. In addition, the number of patients included in this study was small and therefore the efficacy of the chemotherapy regimens could not be assessed. Yet, the obtained results can be used to develop new studies on the optimal treatment, especially among larger study populations in ampullary cancer and duodenal adenocarcinoma.

To conclude, this population-based study reflected the limited guidelines available for patients diagnosed with ampullary and duodenal cancer. Patients diagnosed with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and distal cholangiocarcinoma were treated according to the available guidelines and recruiting trials. The chemotherapy regimens in patients diagnosed with duodenal adenocarcinoma were in agreement with the colorectal cancer guidelines, while the large variation in chemotherapy regimens in ampullary cancer reflects the different guidelines expected to be consulted.

Ethical approval

The study protocol for the present analysis was approved by the scientific committee of the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group.

| Abbreviations | ||

| 5-FU | = | fluorouracil; |

| CAPOX | = | capecitabine plus oxaliplatin |

| FOLFIRINOX | = | 5-fluorouracil plus irinotecan plus oxaliplatin |

| FOLFOX | = | 5-flourouracil plus oxaliplatin |

| IQR | = | interquartile range |

| NCR | = | Netherlands Cancer Registry |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry as well as the IKNL staff for scientific advice.

Disclosure statement

JDV has served as a consultant for Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, Pierre Fabre, and Servier, and has received institutional research funding from Servier. All outside the submitted work;

SG reports grants from Roche, grants from Pfizer, grants from Novartis, grants from Lilly, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Gilead, personal fees from AstraZeneca. All outside the submitted work;

VT-H reports grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Accord Healthcare, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Eisai, grants from Daiichi Sankyo, grants from Gilead. All outside the submitted work;

LV-VI reports non-financial support from Servier, non-financial support from Pierre Fabre, non-financial support from Roche. All outside the submitted work;

JW reports grants and non-financial support from Servier, non-financial support from MSD, non-financial support from AstraZeneca, grants and non-financial support from Celgene, grants from Halozyme, grants from Merck, grants from Roche, grants from Pfizer, grants from Amgen, grants from Novartis. All outside the submitted work;

The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fernandez-Cruz L. Periampullary carcinoma. In: Holzheimer R, Mannick J, editors. Surgical treatment: evidence-based and problem-oriented. Munich, Germany: Zuckschwerdt; 2001.

- Sarmiento JM, Nagomey DM, Sarr MG, et al. Periampullary cancers: are there differences? Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(3):543–555.

- Meijer LL, Alberga AJ, de Bakker JK, et al. Outcomes and treatment options for duodenal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(9):2681–2692.

- Pancreascarcinoom. Landelijke richtlijn: Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde. 2019. Available from: https://dpcg.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Richtlijn_Pancreascarcinoom_2019.pdf

- Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C, et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(5):v56–68.

- Galweg- en galblaascarcinoom. Landelijke richtlijn. Landelijke werkgroep Gastro-intestinale tumoren; 2013. Available from: Galweg- en Galblaascarcinoom - Algemeen - Richtlijn - Richtlijnendatabase

- Valle JW, Borbath I, Khan SA, et al. Biliary cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(5):v28–v37.

- Shroff RT, Kennedy EB, Bachini M, et al. Adjuvant therapy for resected biliary tract cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(12):1015–1027.

- Stein A, Arnold D, Bridgewater J, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared to observation after curative intent resection of cholangiocarcinoma and muscle invasive gallbladder carcinoma (ACTICCA-1 trial) - a randomized, multidisciplinary, multinational phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:564.

- Hester CA, Dogeas E, Augustine MM, et al. Incidence and comparative outcomes of periampullary cancer: a population-based analysis demonstrating improved outcomes and increased use of adjuvant therapy from 2004 to 2012. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119(3):303–317.

- Percy C, Holten V, Muir CS, et al. 1990. International classification of diseases for oncology. Percy C, Holten V, Muir CS, editors. 2nd ed. World Health Organization.

- Edge SB, Byrd DR, Carducci MA, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. Vol. 7. New York (NY): Springer; 2010.

- Amin MB, Edge SB. American joint committee on C. AJCC cancer staging manual. New York (NY): Springer; 2017.

- Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the Dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(16):1763–1773.

- Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2395–2406.

- de Jong EJM, van der Geest LG, Besselink MG, et al. Treatment and overall survival of four types of non-metastatic periampullary cancer: nationwide population-based cohort study, HPB, 2022.

- Colorectaal Carcinoom (CRC). Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde; 2020. Available from: Startpagina - Colorectaal carcinoom (CRC) - Richtlijn - Richtlijnendatabase.

- Argiles G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, et al. Localised Colon cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(10):1291–1305.

- Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1386–1422.

- Zaanan A, Costes L, Gauthier M, et al. Chemotherapy of advanced small-bowel adenocarcinoma: a multicenter AGEO study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(9):1786–1793.

- Neoptolemos JP, Moore MJ, Cox TF, et al. Ampullary cancer ESPAC-3 (v2) trial: a multicenter, international, open-label, randomized controlled phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):LBA4006–LBA4006.

- Bonet M, Rodrigo A, Vazquez S, et al. Adjuvant therapy for true ampullary cancer: a systematic review. Clin Transl Oncol. 2020;22(8):1407–1413.

- Moekotte AL, Malleo G, van Roessel S, et al. Gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy in subtypes of ampullary adenocarcinoma: international propensity score-matched cohort study. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1171–1182.

- Pea A, Riva G, Bernasconi R, et al. Ampulla of vater carcinoma: molecular landscape and clinical implications. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(11):370–380.

- Casolino R, Paiella S, Azzolina D, et al. Homologous recombination deficiency in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and prevalence Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(23):2617–2631.

- Bakens MJ, Geest LG, Putten M, et al. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer varies widely between hospitals: a nationwide population-based analysis. Cancer Med. 2016;5(10):2825–2831.

- Mackay TM, Smits FJ, Roos D, et al. The risk of not receiving adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a nationwide analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22(2):233–240.

- Valle JW, Palmer D, Jackson R, et al. Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):504–512.