Abstract

Background

The proportion of patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that do not receive systemic anticancer treatment and the reasons for lack of treatment are largely unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and overall survival of this patient group and reasons for omission of treatment.

Material and methods

This retrospective, single-center cohort study from Rigshospitalet, Denmark included patients diagnosed with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma during the study period from 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2016 who did not receive systemic anticancer treatment. Patients were identified through the Danish Pathology Register and the electronic medical records.

Results

100 patients were included, representing 34% of all patients diagnosed with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma at Rigshospitalet during the study period. Lack of treatment was most often due to poor physical condition (59%), decreased renal function (15%), or patient preferences (14%). Median overall survival was 1.9 months (95% CI: 1.6–2.8 months).

Conclusion

One in three patients diagnosed with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma in the pre-immunotherapy era did not receive systemic anticancer treatment. Prompt identification of advanced disease and interventions to optimize these patients for treatment are essential. Our findings underscore the compelling need for novel, better tolerated treatment regimens in this frail patient group.

Background

Locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC) is largely an incurable disease with a poor prognosis [Citation1]. Before the introduction of effective chemotherapy, median overall survival (OS) rarely exceeded 3–6 months [Citation1]. Despite the introduction of immune-checkpoint-inhibitors (ICIs) in the treatment of mUC in 2017, cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy remains the preferred standard first-line treatment [Citation2]. It is well known that approximately 50% of patients with mUC are cisplatin-ineligible due to impaired renal function, poor performance status, congestive heart failure, hearing loss or peripheral neuropathy [Citation3,Citation4]. Some of the cisplatin-ineligible patients receive carboplatin-based chemotherapy or, since 2017, ICI in the presence of positive PD-L1 expression as defined by different concomitant diagnostic assays [Citation3,Citation5]. The proportion of patients with mUC who never receive systemic anticancer treatment (SAT) is less clear; reported rates range from 24% to 58%, which is higher than for some other cancer types [Citation6–10]. The specific modifiable and non-modifiable reasons for lack of treatment have never been studied [Citation8]. Identification of modifiable targets for interventions is necessary to possibly make more patients eligible for treatment. Further, knowledge of specific reasons for omission of treatment may also be used to guide drug development in this patient group.

We conducted a retrospective, single-center cohort study in order to explore the prevalence, characteristics, and OS of patients with mUC who did not receive SAT and to investigate the reasons why treatment was abstained.

Material and methods

Setting

All Danish residents are equally entitled to tax-financed, free of charge healthcare. Rigshospitalet is a university hospital in the capital of Denmark offering highly specialized uro-oncologic diagnostics and treatment to patients from a large area both inside and outside the capital region of Denmark.

A close collaboration on patients with mUC is established between Department of Urology and Department of Oncology, Rigshospitalet. Diagnostics are performed at Department of Urology. Patients considered possible candidates for SAT are referred to Department of Oncology for further assessments, whereas patients in poor physical condition considered definitely ineligible for treatment are not referred.

During the inclusion period from 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2016, ICIs were not yet approved by the Danish Medicines Council and SAT for mUC consisted solely of chemotherapy [Citation11].

Data sources and study population

Reporting of all procedures and diagnoses obtained through histolopathologic examination of cell and tissue samples is mandatory in Denmark. Procedures and diagnoses are coded by the examining pathologists using Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED). Information is stored in Patobank, which is part of the Danish Pathology Register [Citation12].

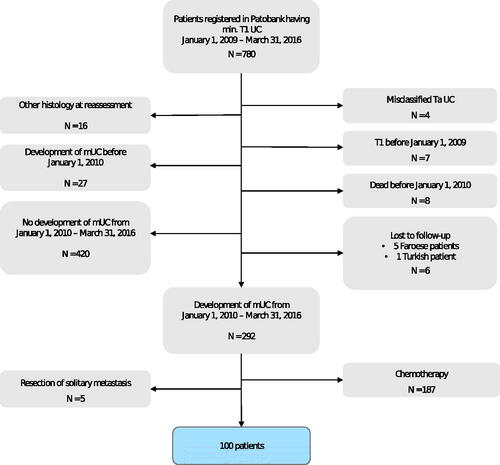

From Patobank, we extracted a list of all patients diagnosed with ≥ pT1 urothelial carcinoma (UC) including locally advanced or metastatic disease at Rigshospitalet in the period 1 January 2009 to 31 March 2016 using the following SNOMED codes: M81203, M81204, and M81206. Primary tumors originating in the upper urinary tract, the bladder and urethra were included. By the use of the unique 10-digit personal identification number assigned to all Danish residents, we then screened the electronic medical records (EMRs) of these patients to identify those who developed mUC during the inclusion period from 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2016 (). The present study cohort consisted of patients with newly diagnosed mUC during the inclusion period and who did not receive SAT ().

Figure 1. Flow diagram depicting the population screened for study enrollment, reasons for exclusion and the final study population.

Data extraction took place from March 2020 to December 2021 and was carried out by the primary investigator (resident in oncology, L. H. O.) and entered in a REDCap database.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

Gender, age, primary tumor location, TNM stage, prior treatments, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), location of metastases, and renal function were recorded at the time of study inclusion and presented descriptively. Renal function was recorded as chromium-51-ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid clearance (Cr-EDTA clearance) if performed, otherwise as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from serum creatinine measurements. Reasons for not initiating chemotherapy were captured according to the following predefined categories: (1) poor physical condition referring to a poor general health status as perceived by the treating physician, (2) decreased renal function, (3) heart failure, (4) hearing loss, (5) peripheral neuropathy, (6) other comorbidity, (7) solely patients own choice, (8) death before decision on anticancer treatment, and (9) unknown. Multiple reasons could be stated. OS was defined as time from diagnosis of mUC to date of death from any cause and calculated and presented using the Kaplan–Meier estimator of the survival curve. Estimates and 95% confidence intervals for three-, six- and 12 months survival are reported. Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.1.) [Citation13].

Results

From 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2016, 100 of 292 (34%) patients diagnosed with mUC at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark did not receive SAT (). Two-third of the patients were men and the median age at diagnosis of mUC was 72 years. Sixty-eight patients (68%) were initially diagnosed with local disease and previously received curatively intended treatment in the form of radical cystectomy (53%), nephroureterectomy (7%), curative radiotherapy (7%), or other form of tumor resection (1%) (). Of the patients who had undergone radical cystectomy, five patients had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC); all five patients had disease progression within 12 months of terminating NAC (median time 8 months).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 100 patients diagnosed with mUC at Rigshospitalet, Denmark in the period 1 January 2010 to 31 March 2016, who did not receive systemic anticancer treatment and of 952 patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial tract cancer of different histologic subtypes who received SAT in Denmark during the same inclusion period.

At the time of diagnosis of mUC, approximately one-third had liver metastases. Lung and bone metastases were present in 19% and 30% of patients, respectively. ECOG PS was registered in 31 patients (31%), most of whom had ECOG PS 3 (20% of all patients). Registration of specific PS was more common in patients evaluated for SAT at the oncology department (25 of 41 patients (61%)) than in patients solely evaluated at the urology department (6 of 59 patients (10%)). Renal function was evaluated by Cr-EDTA clearance in 16 patients (16%) and by eGFR in 72 patients (72%); in 12 patients (12%) no data on renal function was reported. In patients evaluated by Cr-EDTA, mean clearance was 40.3 ml/min compared to 58.1 ml/min in patients only evaluated by eGFR.

The most common reported reason to abstain from chemotherapy was poor physical condition (59%), decreased renal function (15%), and patient preferences (14%) (). In three patients, more reasons for lack of treatment were registered; patient 1: poor physical condition, decreased renal function and heart failure; patient 2: poor physical condition and decreased renal function; patient 3: poor physical condition and decreased renal function. Among patients with poor physical condition stated as reason for lack of treatment, 33 had no ECOG PS registration, 24 had ECOG PS 3–4, and 2 had ECOG PS 2. Forty-one patients (41%) were assessed for chemotherapy eligibility at the oncology department. For the remaining patients, the decision not to treat was made at the urology department and these patients were never evaluated by an oncologist.

Table 2. Reasons for lack of chemotherapy as indicated in the electronic medical records of 100 patients with mUC not receiving systemic anticancer treatment.

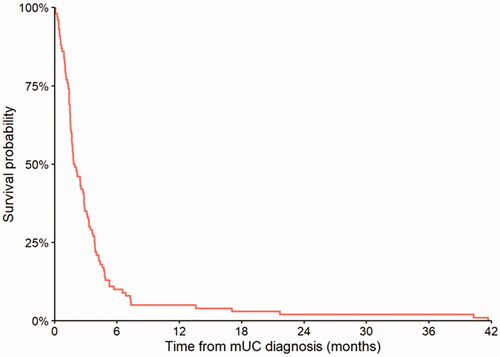

All patients died during the follow-up period. Median OS was 1.9 months (95% CI: 1.6–2.8 months) (). Survival rates at three, six and 12 months were 35% (95% CI: 27–46%), 10% (95% CI: 6–18%), and 5% (95% CI: 2–12%), respectively (). A survival curve is presented in .

Figure 2. Survival curve from diagnosis of mUC to death in 100 patients with mUC not receiving systemic anticancer treatment.

Table 3. Median OS plus 3-, 6- and 12-months OS rates in 100 patients with mUC not receiving systemic anticancer treatment and median OS in 952 patients with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic urothelial tract cancer of different histologic subtypes who received SAT in Denmark during the same inclusion period.

Discussion

In this retrospective, single-center cohort study, we found that 34% of patients with newly diagnosed mUC did not receive SAT most often due to poor physical condition, decreased renal function or patient preferences. The prognosis was poor with a median OS of 1.9 months (95% CI: 1.6–2.8 months). To our knowledge, this is the first study to report reasons, as indicated in the EMRs, for lack of SAT in patients with mUC.

Complete inclusion of patients through thorough pathology coding practices in Denmark and the use of the unique 10-digit personal identification number are major study strengths [Citation14,Citation15]. Data manually collected from the EMRs as well as complete follow-up in terms of survival are other study strengths [Citation16]. Together, these ensure high data validity and generalizability to other Danish as well as international bladder cancer populations.

We present data from the pre-ICI time period, in which SAT in Denmark consisted solely of chemotherapy. These data are still highly relevant, as chemotherapy remains the preferred anticancer treatment in this patient group. Further, according to Danish treatment guidelines criteria for ICI treatment largely resemble those for carboplatin-based chemotherapy [Citation12]. Therefore, ICI does not constitute a novel treatment regimen for most patients deemed both cisplatin- and carboplatin ineligible [Citation5,Citation12,Citation17].

The gender distribution was similar to the broad mUC population in Denmark [Citation18]. Somewhat surprisingly, median age was just a little higher than that of patients with mUC initiating first-line chemotherapy (72 versus 69 years) [Citation18]. Accordingly, there are no reasons to suspect that lack of SAT was based solely on age, which is in line with treatment guidelines [Citation12].

ECOG PS was only registered in a proportion of patients, most often patients evaluated at the oncology department. This scale is largely an oncologic assessment tool helping to direct clinical decision making and is only to a lesser extend incorporated in urology daily practice, which may explain part of the registration lack as most patients in the present study were evaluated at the urology department [Citation19]. In 59% of the patients, poor physical condition was stated as the reason for treatment renouncement. As expected, this included the 24% of patients registered with ECOG PS 2–3 and thus directly chemotherapy ineligible according to treatment guidelines, but also two patients with ECOG PS 2, which alone does not contraindicate chemotherapy and 33% with no ECOG PS registration [Citation12].

Liver metastases were present in 32% of patients, which is a significantly higher rate than in patients with mUC receiving chemotherapy, for whom we previously reported a liver metastases rate of 14% [Citation18]. The presence of liver metastases is a well-documented adverse prognostic factor for OS in patients with mUC [Citation20]. In addition, 30 patients (30%) had bone metastases and four patients (4%) had brain metastases compared to 16% and 1%, respectively, of patients with mUC initiating chemotherapy [Citation18]. Taken together, this demonstrates that patients who do not receive SAT often have severely disseminated disease and furthermore that tumor burden, likely due to corresponding poor physical condition, seems a central element in clinical decision making. This emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis of advanced disease, both in patients initially presenting with mUC and in patients progressing following initial localized disease [Citation21]. Throughout the inclusion period, national guidelines for follow-up after curatively intended treatment for UC have existed with recommendation of regular assessments including CT scans for a minimum of 2 years. It cannot with certainty be excluded that lack of implementation of follow-up after curative treatment is part of the reason for the large tumor burden in the present patient cohort and in turn for the lack of SAT in these patients.

According to practice, only patients considered possible candidates for SAT are referred to Department of Oncology for assessments and initiation of SAT. Based on the availability of national treatment guidelines and the close collaboration on mUC patients, we do not suspect the evaluation of SAT eligibility done at the urology department to impact the prevalence of and reasons for omission of treatment demonstrated in this study. This is further underscored by the poor median OS of included patients.

In some patients, prior treatment for localized disease may explain the lack of SAT. The five patients who received NAC all progressed within 12 months of terminating treatment and were thereby ineligible for further platinum-based chemotherapy, but not for vinflunine, which was recommended second-line treatment during the study period [Citation12].The radical cystectomy or nephroureterectomy procedures performed in the majority of patients could have resulted in decreased renal function, which in turn might have deemed some patients ineligible for chemotherapy [Citation3,Citation4,Citation22,Citation23]. However, we have no information to characterize the decreased renal function present in our patient cohort and as such, we cannot fully evaluate the potential for renal function optimization. Yet, increased focus on potentially reversible pre-renal and post-renal failure due to obstructive processes and following interventions including discontinuation of nephrotoxic medication and relief of obstruction by stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy, respectively, might improve renal function in some patients to a degree allowing SAT [Citation24].

In 14% of patients, the reason for lack of chemotherapy was patient preferences. This infers that omission of treatment does not equal treatment ineligibility. We have no data on why some of the patients declined SAT. In other cancers, an association between lower socioeconomic position (SEP) and lack of SAT has been demonstrated, possibly due in part to less treatment information provided and less involvement in clinical decision making in this patient group [Citation25]. The association between low SEP and UC is well-established [Citation26]. Although we have no information on SEP of the present study population, it is plausible that SEP might have impacted the decision of abstaining from treatment in some patients. Further, one could speculate that chemotherapy associated toxicities or the treatment not being curative discouraged a proportion of patients from treatment. Some of these patients might had been willing to receive ICI treatment, despite only a subpopulation of patients benefitting from this treatment [Citation27,Citation28]. Future drug development of increased efficacy and with a more favorable toxicity profile might incline more patients to initiate treatment [Citation7,Citation10].

The proportion of patients with mUC who did not receive SAT is similar to the findings in a study by Fisher et al. [Citation9], but higher than reported by Sonpavde et al. and Bamias et al. [Citation6,Citation8], and lower than demonstrated by Galsky and colleagues [Citation7]. The differences could be explained by dissimilarities in diagnostics between countries with different health care systems and health care funding (tax-financed versus insurance-based) and corresponding differences in patient characteristics. For the Galsky study, the difference in prevalence is likely explained by the higher median age of untreated patients [Citation7].

The literature describing reasons for lack of treatment is scarce. Although Bamias et al. found an association between lack of treatment and older age, non-Caucasian race, non-UC histology, higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, more frequent use of perioperative chemotherapy and management of primary tumors, as well as treatment at low-volume centers, no previous studies reported on the specific reasons for abstaining from SAT in patients with mUC [Citation8]. The association between comorbidity and lack of treatment reported by Bamias is to be expected, as comorbidity to a varying degree impact the risk/benefit ratio of SAT. Due to insufficient comorbidity data in the EMRs, we were not able to report on comorbidities in the present study cohort. We cannot exclude that poor physical condition stated as reason for lack of treatment may in part be due to comorbidity.

OS demonstrated in this cohort of patients with mUC not receiving SAT is significantly lower than the OS of 3–6 months reported in untreated patients with mUC before development of effective chemotherapy [Citation1]. This suggests that patients with mUC who do not receive SAT might have more aggressive disease and/or a worse general condition than the average patient with mUC. Interestingly, the OS in our patient cohort is notably lower than in previous reports (3.7–5.7 months) from after the introduction of SAT in mUC [Citation7–9]. We believe this is due to differences in patient characteristics including tumor burden at diagnosis and the proportion of patients initially presenting with mUC.

We previously reported OS in patients with mUC treated in the real-world clinical setting to be comparable to OS in clinical trials [Citation18]. Yet, the demonstration of approximately one-third of patients with mUC not receiving SAT underscores the discrepancy between treatment efficacy as demonstrated in clinical trials and treatment effectiveness when applied to the general mUC population [Citation29]. Consequently, substantial unmet treatment needs remain, and further drug development with more favorable toxicity profiles is urgently warranted.

In daily practice, clinical assessment tools are warranted to help predict which patients with mUC could be optimized for SAT and which patients would benefit more from supportive care alone. Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a multidisciplinary assessment considered the gold standard for evaluation of an older patient’s health situation [Citation3]. CGA can support clinical decision making by uncovering the functional capabilities and limitations of patients and directing interventions thereby possibly optimizing the general condition of frail patients. The CGA, however, is time consuming and not necessary for fit and healthy older patients. Several screening tools including G8 have been developed to identify which patients could benefit for a CGA [Citation30]. We believe that implementation of these screening tools is feasible and would be beneficial in patients with bladder cancer in general and in this subgroup of frail patients in particular.

Study limitations mainly confer to the retrospective study design. Some data are missing, particularly regarding ECOG PS, and we were not able to obtain valid comorbidity data. Due to the relatively small data set, we were not able to adjust for potential confounders including age, gender, ECOG PS and renal function.

Conclusions

In the investigated cohort, one-third of patients with mUC did not receive SAT, most often due to poor physical condition, decreased renal function or patient preferences. Earlier detection of advanced disease in addition to assessment of and attempts to improve physical performance and renal function to allow SAT should be a focus in this patient group. Novel and better tolerated treatment regimens with more favorable toxicity profiles than the currently available therapies are urgently needed in this frail patient group.

Acknowledgments

No other persons than the corresponding author and co-authors have made substantial contributions to this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

Lise H. Omland has received a honoraria of DKK 5000 in December 2020 for participating in a MSD bladder cancer meeting.

Helle Pappot has received research grants from Roche, MSD, Pfizer and Merck.

No funding or financial support was received for this project.

Data availability statement

Data can be provided, except for personally identifiable information.

References

- von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3068–3077.

- Horwich A, Babjuk M, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU–ESMO consensus statements on the management of advanced and variant bladder cancer—an international collaborative multi-stakeholder effort: under the auspices of the EAU and ESMO guidelines committees. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(11):1697–1727.

- Bellmunt J, Mottet N, De Santis M. Urothelial carcinoma management in elderly or unfit patients. EJC Suppl. 2016;14(1):1–20.

- Galsky MD, Hahn NM, Rosenberg J, et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer “unfit” for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2432–2438.

- Witjes JA, Babjuk M, Bellmunt J, et al. EAU-ESMO consensus statements on the management of advanced and variant bladder cancer—an international collaborative multistakeholder effort†. Eur Urol. 2020;77(2):223–250.

- Sonpavde G, Watson D, Tourtellott M, et al. Administration of cisplatin-based chemotherapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma in the community. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10(1):1–5.

- Galsky MD, Pal SK, Lin SW, et al. Real-world effectiveness of chemotherapy in elderly patients with metastatic bladder cancer in the United States. Bladder Cancer. 2018;4(2):227–238.

- Bamias A, Tzannis K, Harshman LC, RISC Investigators, et al. Impact of contemporary patterns of chemotherapy utilization on survival in patients with advanced cancer of the urinary tract: a retrospective international study of invasive/advanced cancer of the urothelium (RISC). Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):361–369.

- Fisher MD, Shenolikar R, Miller PJ, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in stage IV bladder cancer in a community oncology setting: 2008–2015. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(6):e1171–e1179.

- Small AC, Tsao CK, Moshier EL, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of patients with metastatic cancer who receive no anticancer therapy. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5947–5954.

- Dohn LH, Omland LH, Stormoen DR, et al. Status of metastatic bladder cancer treatment illustrated by a case. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2021;37(1):151113.

- The Danish Bladder Cancer Group- Clinical guidelines (in Danish). Available from: http://www.skejby.net/DaBlaCa-web/DaBlaCaWEB.htm

- R Core Team. 2021. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. URL Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Adelborg K, et al. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:563–591.

- Cornet R, de Keizer N. Forty years of SNOMED: a literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(S1):S2.

- Kim HS, Lee S, Kim JH. Real-world evidence versus randomized controlled trial: clinical research based on electronic medical records. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(34):e213.

- Szabados B, Prendergast A, Jackson-Spence F, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in front-line therapy for urothelial cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. Published Online. 2021; 82:212–222.

- Omland LH, Lindberg H, Carus A, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and overall survival in locally advanced and metastatic urothelial tract cancer patients treated with chemotherapy in Denmark in the preimmunotherapy era: a nationwide, population-based study. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2021;24:1–8.

- Neeman E, Gresham G, Ovasapians N, et al. Comparing physician and nurse eEastern cooperative oncology group performance status (ECOG‐PS) ratings as predictors of clinical outcomes in patients with cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(12):e1460–e1466.

- Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1850–1855.

- Khochikar M. Rationale for an early detection program for bladder cancer. Indian J Urol. 2011;27(2):218–225.

- Rouanne M, Gaillard F, Meunier ME, et al. Measured glomerular filtration rate (GFR) significantly and rapidly decreases after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16145.

- Vejlgaard M, Maibom SL, Stroomberg HV, et al. Long-term renal function following radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Urology. Published Online. 2021;160:147–153.

- Campbell GA, Hu D, Okusa MD. Acute kidney injury in the cancer patient. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):64–71.

- Konradsen AA, Lund CM, Vistisen KK, et al. The influence of socioeconomic position on adjuvant treatment of stage III Colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2020;59(11):1291–1299.

- Eriksen KT, Petersen A, Poulsen AH, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from cancers of the kidney and urinary bladder in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994–2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):2030–2042.

- Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):67–76.

- Balar AV, Castellano D, O'Donnell PH, et al. First-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1483–1492.

- Sargent D. What constitutes reasonable evidence of efficacy and effectiveness to guide oncology treatment decisions? Oncologist. 2010;15(S1):19–23.

- Mohile SG, Dale W, Somerfield MR, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2326–2347.