Background

The selection of patients with truly oligometastatic disease (OMD) is complex. The oligometastatic state likely differs between cancer types and is best defined biologically [Citation1]. However, surrogate criteria have been applied in the absence of a robust biological signature to identify patients eligible for an OMD strategy. The most used categorization of OMD relies on the number of radiographically visualized metastatic sites. Several attempts have been made to define a threshold for the number of metastatic lesions that reflects patient survival and defines an OMD state [Citation2–9].

In 2020, ESTRO (European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology) and ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology) published an OMD consensus document on the identification and treatment of OMD based on expert opinions and a systematic literature review [Citation10]. They concluded that OMD can be defined as 1–5 safely treatable metastatic lesions, with a controlled primary tumor being optional. The same year EORTC (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer) and ESTRO proposed a system for characterization and classification of OMD [Citation11], which is being prospectively evaluated in the OligoCare study (EORTC 1811 study, NCT03818503).

In 2018, the Danish National Research Centre for Radiotherapy (DCCC-RT) was established and initiated multiple research initiatives, including a group focusing on OMD. In the preparation of a nationwide prospective benchmark trial of local ablative therapy for OMD, we conducted a nationwide survey in a real-world cohort of clinicians to broadly assess the general perception and definition of the OMD concept and explore the patterns of care regarding referral for an ablative treatment strategy.

Material and methods

Target group

This cross-sectional, population-based survey included clinicians working in the Danish oncology departments. Both medical and clinical oncology specialists and clinical oncology trainees were included in the target group. In Denmark, the medical oncology and the therapeutic radiology specialities were merged in 2004 as a clinical oncology speciality with a revised education program. The clinical oncologist master both the prescription of systemic treatments and the planning of radiotherapy, but only a fraction of the clinicians ends up practising radiation oncology after specializing. Medical oncologists do not practise radiotherapy planning. This was considered when we designed the survey, as aspects concerning the technical use of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) were not included.

Survey design

We used a single-stage sampling technique, using an online survey tool (Google Forms), where responders could answer anonymously. The survey was designed with 18 questions in three parts. An introduction describing the aim and OMD definitions. A demographic part with five questions regarding responder workplace, speciality, educational level, and participation in radiotherapy planning or tumor boards. Lastly, 13 multiple-choice questions addressing the interpretation and clinical handling of OMD, e.g., how many metastases in how many organs the responder would treat, referral patterns, preferences regarding local ablative modalities, and if all patients should be discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board before offering SBRT to patients with OMD. A text box for free commenting was available for each question. A translated version of the Danish questionnaire is presented in Supplementary material A.

To avoid bias, we used the following definitions in the introduction to the survey. OMD was defined as a state with a few metastases with or without a primary tumor. Oligo-progressive disease (OPD) was defined as the progression of a few metastases with otherwise stable disease. Local ablative treatment included surgery, other invasive procedures, and SBRT.

The survey was sent out twice to two different test groups with 15 representative responders for comments and revised accordingly to create the final version of the questionnaire. The two test groups worked in the same department but with different disease entities (colorectal and lung cancer).

Data collection and statistics

We contacted the heads of departments from the eleven Danish oncology centers in 2020 to obtain the email addresses of their staff physicians. The request was re-sent if they did not respond.

The data were analyzed using basic descriptive statistics, and results are generally presented as percentages of responders who completed the survey. The statistical program R (version 4.0.3) was used for the descriptive statistic and graphic design. Ethics approval was not required. The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration. For reporting, we used the CROSS consensus-based checklist [Citation12]. The checklist is presented in Supplementary material B.

Results

Survey population

Nine of the 11 department leaderships responded and forwarded the emails of their staff physicians. Invitations were sent to 461 clinicians at nine centers, six with radiotherapy facilities. A total of 102 clinicians from seven different centers completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 22%. Information on the response rates for each question is reported in Supplementary material C.

Most responders (67%) were specialists in clinical oncology, 25% were clinical oncology trainees, and 2% were specialists in medical oncology. The remaining 6% were specialized in palliative medicine or worked in unclassified positions. Five responders (5%) were from oncology departments without radiotherapy facilities. Most responders (95%) were from academic centers. More than half of the responders (58%) practised radiation oncology, whereas 42% did not but still referred patients to radiotherapy. The majority (81%) of the responders worked with one or more of the following disease entities: urogenital, lung, breast, or gastrointestinal cancer. Two-thirds of the responders (66%) attended multidisciplinary tumor board conferences.

Definition and view on oligometastatic disease

The majority (93%) of the responders expected that cure or long-lasting disease control could be achieved for selected OMD patients if an ablative strategy (e.g., surgery, other invasive procedure, or SBRT) is applied.

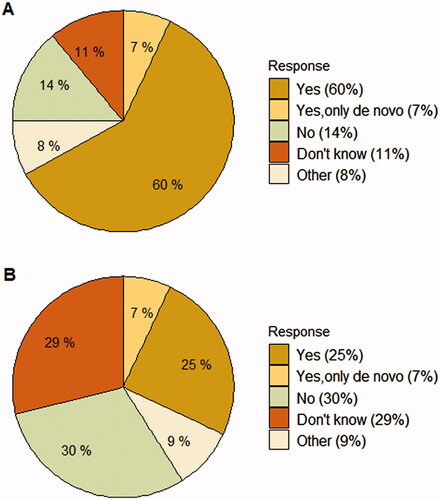

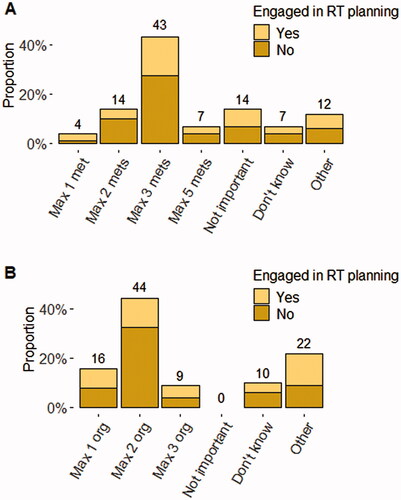

The majority (43%) of responders identified a preferred threshold of ≤ 3 metastases when applying an ablative strategy for patients with OMD, and only 7% were willing to treat up to five metastases (). Fourteen responders (14%) answered that the number of metastases was not a determining factor. Most responders (44%) preferred a threshold of up to two involved organs when applying an ablative strategy for patients with OMD (). Respondents’ engagement in radiation oncology did not influence the preferred threshold ().

Figure 1. The preferred threshold of metastases/organs eligible for an ablative strategy in patients with OMD. (A) The preferred threshold of metastases (mets), the responders were willing to treat when applying an ablative strategy in patients with OMD. (B) The preferred threshold of involved organs (org), the responders were willing to treat when applying an ablative strategy in patients with OMD.

When the same questions were asked regarding patients with OPD, there was a tendency to set a lower threshold for the acceptable number of metastases/organs eligible for an ablative strategy. The responders were almost equally divided between accepting a threshold of one (25%), two (27%), or three (25%) metastases, and 42% identified one organ as the preferred limit.

In a post hoc analysis, neither SBRT experience nor the available equipment (MR-linac) at the departments influenced the preferred threshold for the number of metastases or involved organs in patients with OMD and OPD (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p > 0.2).

Referral pattern

Responders found that patients with colorectal cancer (64%), breast cancer (60%), lung cancer (57%), kidney cancer (45%), and prostate cancer (45%) were most suitable for an OMD strategy with SBRT. The most accepted anatomical sites for metastases-directed SBRT/stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) as part of an ablative OMD strategy were CNS (86%), lung (76%), bone (55%), and liver (54%).

Ninety responders (88%) stated their indication for referring to SBRT, and the most common reasons were to gain local control (82%) and relieve symptoms (32%). Sixteen responders stated a reason for seldom or never referring patients for SBRT. The most common reason was that they knew too little about SBRT to choose this strategy (8%). The lack of necessary equipment was never stated as a limitation for SBRT referral.

Most responders (60%) answered that it was necessary to discuss all patients with OMD at a multidisciplinary tumor board before referring to SBRT (), but only 25% described that this occurred in their usual clinical practice ().

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first nationwide survey to address the perception and patterns of care on OMD among clinical working physicians responsible for the whole treatment course (medical and ablative strategy). It shows that clinicians believe local ablative therapy can improve survival and have embraced and, to some extent, integrated the OMD concept into daily clinical practice.

The response rate in this survey was 22%, which is in line with response rates from other surveys using a similar methodology [Citation5,Citation6], and acceptable when considering the responder group (clinicians with different backgrounds and not necessarily engaged in the planning of the radiotherapy course).

The responders are representative of the target population in educational level, organ-specific speciality, access to radiotherapy facilities, and geography. However, responders with a medical oncology background may be underrepresented.

Earlier surveys have addressed the same topic but in more selected responder populations, e.g., a selected group of SBRT experts or members of national and international radiation oncology societies [Citation3–6]. They may not always represent the clinical working physicians, referring these patients to an ablative strategy.

This survey was conducted during the same period as Lievens et al. published the ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document, where OMD is defined as 1–5 safely treatable metastatic lesions [Citation11]. Our responders preferred a threshold of ≤ 3 metastases and were more restrictive regarding a preferred threshold for OMD than what the highly specialized consensus group recommended. In the survey, the presented OMD scenarios were highly simplified. Other factors, e.g., size, timing from diagnosis, favorable disease-specific organ location, relation to nearby organs of risk, comorbidity, and tumor biology, were not addressed and would have nuanced the questions and affected the response.

Our responder group highlighted patients with oligometastatic colorectal, breast, lung, kidney, and prostate cancer as most suitable for local ablative therapy with SBRT. This is in concordance with the included populations in published phase 2 studies of OMD [Citation13–17].

Most of our responders (60%) found it necessary to discuss patients with OMD at a multidisciplinary tumor board, but only 25% described this as the case in daily clinical practice. These findings align with results from the Italian OLIGO-AIRO survey where most responders (66%) suggested an interdisciplinary discussion [Citation6]. This illustrates a paradigm shift and change of practice within the oncology society. The increasing use of multimodality strategies increases the need for discussing patients at multidisciplinary tumor boards and requires more resources. However, an unlimited application of local ablative strategies, without evidence of clinical benefit, registration of toxicity or consensus on referral patterns, could potentially worsen the clinical outcome for the patients and challenge the health system financially.

In Denmark, access to radiotherapy resources and trained professionals is high [Citation18]. This is reflected in the survey, as none of the responders pointed out a lack of human resources or necessary equipment as a reason for not referring to SBRT.

Since the survey was conducted in 2020, a national OMD strategy has been promoted, and several OMD protocols have finished recruitment in Denmark (NCT05101824, NCT04407897). International progress has been made, and clinicians’ perception and clinical handling of OMD might have changed over the years in favor of a more aggressive strategy. However, we still await outcome results from the national initiatives, international phase III protocols [Citation19,Citation20], and the OligoCare study.

This survey has served as an instrument for reaching a national consensus on the definition of OMD to design a nationwide prospective benchmark study, the OLIGO-DK. We have involved representatives from all the Danish centers to develop a national trial where patients with OMD, classified according to the definition proposed by Guckenberger et al. [Citation11], can be referred to local ablative treatments regardless of the primary tumor or target location. This will secure a prospective registration on the referral pattern, continuous gathering and exchange of knowledge nationally.

Conclusion

In this real-world nationwide survey, we found a general agreement among clinicians working at the oncology departments in Denmark on the selection criteria for ablative treatment of OMD. A threshold of three metastases in up to two organs was preferred for an ablative strategy in patients with OMD. Only 7% were willing to treat up to five metastases.

Patient consent statement

Not relevant, as this is a survey with clinicians as responders.

Ethics approval (include appropriate approvals or waivers)

Not relevant for this survey.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Mette van Overeem Felter, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Weichselbaum RR, Hellman S. Oligometastases revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(6):378–382.

- Aluwini SS, Mehra N, Lolkema MP, Dutch Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer Working Group, et al. Oligometastatic prostate cancer: results of a Dutch multidisciplinary consensus meeting. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(2):231–238.

- Dagan R, Lo SS, Redmond KJ, et al. A multi-national report on stereotactic body radiotherapy for oligometastases: patient selection and follow-up. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(5):633–637.

- Jereczek-Fossa BA, Bortolato B, Gerardi MA, Lombardy Section of the Italian Society of Oncological Radiotherapy (Associazione Italiana di Radioterapia Oncologica-Lombardia, AIRO-L), et al. Radiotherapy for oligometastatic cancer: a survey among radiation oncologists of Lombardy (AIRO-Lombardy), Italy. Radiol Med. 2019;124(4):315–322.

- Lewis SL, Porceddu S, Nakamura N, et al. Definitive stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for extracranial oligometastases: an international survey of >1000 radiation oncologists. Am J Clin Oncol. 2017;40(4):418–422.

- Mazzola R, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Antognoni P, et al. OLIGO-AIRO: a national survey on the role of radiation oncologist in the management of OLIGO-metastatic patients on the behalf of AIRO. Med Oncol. 2021;38(5):48.

- Singh D, Yi WS, Brasacchio RA, et al. Is there a favorable subset of patients with prostate cancer who develop oligometastases? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(1):3–10.

- Steenbruggen TG, Schaapveld M, Horlings HM, et al. Characterization of oligometastatic disease in a real-world nationwide cohort of 3447 patients with de novo metastatic breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:pkab010.

- Levy A, Hendriks LEL, Berghmans T, EORTC Lung Cancer Group (EORTC LCG), et al. EORTC lung cancer group survey on the definition of NSCLC synchronous oligometastatic disease. Eur J Cancer. 2019;122:109–114.

- Lievens Y, Guckenberger M, Gomez D, et al. Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: an ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiother Oncol. 2020;148:157–166.

- Guckenberger M, Lievens Y, Bouma AB, et al. Characterisation and classification of oligometastatic disease: a European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology and European Organisation for research and treatment of cancer consensus recommendation. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(1):e18–e28.

- Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Luu Lam Thang T, et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS). J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):3179–3187.

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, et al. Local consolidative therapy Vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(18):1558–1565.

- Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, et al. Consolidative radiotherapy for limited metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(1):e173501.

- Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence: a prospective, randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):446–453.

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): a randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet. 2019; 393(10185):2051–2058.

- Ruers T, Van Coevorden F, Punt CJ, et al. Local treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109: djx015.

- Lievens Y, Dunscombe P, Defourny N, et al. HERO (Health Economics in Radiation Oncology): a pan-European project on radiotherapy resources and needs. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2015;27(2):115–124.

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 4-10 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-10): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):816.

- Olson R, Mathews L, Liu M, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 1-3 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-3): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):380.