Abstract

Introduction

Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) has expanded into the adjuvant setting enhancing the importance of knowledge on the immune-related toxicities and their impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Large phase 3 trials of patients with resected Stage III/IV melanoma found no effect on HRQoL during adjuvant immunotherapy. This study investigates how HRQoL was affected during and after adjuvant immunotherapy in a real-world setting.

Methods

Patients with resected melanoma treated with adjuvant nivolumab from 2018 to 2021 in Denmark were identified using the Danish Metastatic Melanoma Database (DAMMED). The study was performed as a nationwide cross-sectional analysis as a questionnaire consisting of six different validated questionnaires on HRQoL, cognitive function, fatigue, depression, fear of recurrence, and decision regret was sent to all patients in March 2021. To evaluate HRQoL during and after adjuvant treatment, patients were divided into groups depending on their treatment status when answering the questionnaire; patients in active treatment for 0–6 months, patients in active treatment for >6 months, patients who ended treatment 0–6 months ago, and patients who ended treatment >6 months ago.

Results

A total of 271/412 (66%) patients completed the questionnaire. Patients who ended therapy 0–6 months ago had the lowest HRQoL and had more fatigue. Patients in active treatment for >6 months had lower HRQoL and more fatigue than patients who started treatment 0–6 months ago. Patients ending therapy >6 months ago had higher HRQoL and less fatigue compared to patients who ended therapy 0–6 months ago. Multivariable analysis showed an association between HRQoL and treatment status, comorbidity, civil status, and employment status.

Conclusions

Adjuvant nivolumab may affect some aspects of QoL, but the influence seems temporary. Patient characteristics, such as civil status, employment status, and comorbidity were associated with HRQoL.

Introduction

Within the past decade, modern therapies have revolutionized the treatment of advanced melanoma, and the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) and targeted therapies has significantly improved survival [Citation1–4]. Recently, the use of these therapies has expanded into the adjuvant setting [Citation5–8].

Treatment with ICI is associated with a risk of immune-related toxicities, and more than 70% of patients treated with anti-PD-1 agents experience treatment-related adverse events [Citation9–11]. Most adverse events are mild and reversible and can be managed with symptomatic treatment or in some cases a treatment pause. However, some adverse events are severe or even life-threatening and require hospitalization and immediate discontinuation of treatment with ICI, and the occurrence of severe or chronic toxicities may impact the quality of life (QoL) [Citation12]. Large Phase 3 trials analyzing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) showed no clinically significant changes during adjuvant treatment [Citation6,Citation13]. These studies, however, included only one questionnaire giving a more generalized assessment of HRQoL that do not explore the multifaceted aspects of mental health potentially induced by adjuvant immunotherapy. Also, real-world patients are underrepresented in these studies [Citation14].

Knowledge on HRQoL and psychological consequences during and after treatment may be an important tool in the guidance of patients during the difficult choice of adjuvant therapy. We aimed to investigate how anti-PD-1 therapy may influence HRQoL and other selected aspects of mental health in a nationwide cohort of patients with resected Stage III and IV melanoma treated with anti-PD-1 therapy in an adjuvant setting.

Methods

Study design

The study was performed as a national cross-sectional analysis investigating QoL among patients with resected Stage III and IV melanoma who received adjuvant immunotherapy. The STROBE cross-sectional reporting guidelines were used [Citation15]. Patients were identified using the national Danish metastatic melanoma database (DAMMED), in which all Danish patients receiving systemic therapy for melanoma are registered [Citation16]. Patients who received adjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab in Denmark from the introduction on 14 November 2018 to 1 January 2021, were included in the study. Patients, who had relapsed from melanoma after initiation of adjuvant therapy were excluded. A questionnaire developed in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) was sent to all patients in March 2021 in a digital mailbox connected to the unique personal identification number given to all Danish residents. Patients not responding to the questionnaire received the material up to three times.

Information on treatment and patient characteristics (age, sex, center, melanoma subtype, and classification, performance status (PS), and comorbidities) were extracted from DAMMED. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated for each patient [Citation17]. Information on civil status, familial status, highest level of education, and employment status was obtained as part of the questionnaire.

To evaluate the influence of HRQoL over time during and after adjuvant treatment, patients were divided into groups depending on their treatment status at the time of completing the questionnaire; patients in active treatment for 0–6 months, patients in active treatment for >6 months, patients who ended treatment 0–6 months ago, and patients who ended treatment >6 months ago.

Assessment of HRQoL and other aspects of mental health

The European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire core 30 version 3 (EORTC QLQ-C30), is a 30-item questionnaire assessing HRQoL among patients with cancer across nine dimensions; a global scale, five functioning scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social), and three symptom scales (nausea, pain, and fatigue) [Citation18]. Patients provided their answers in a seven-point scale (1 = very poor and 7 = excellent) for the global health scale and a four-point scale (1 = not at all and 4 = very much) for all other scales. Raw scores were transformed into scales ranging from 0 to 100; for global health and the five functioning scales, higher scores indicate a better level of HRQoL [Citation19]. Differences in scores of ≥10 points were considered clinically significant [Citation20,Citation21].

Studies of patients with other cancers receiving chemotherapy, for example patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant treatment, have shown a deterioration in cognitive function after treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy [Citation22,Citation23]; therefore, cognitive function was further investigated with 10 items from the EORTC CAT Core cognitive function item bank [Citation24]. The 10-item scale is scored using T-scoring calculated with a specialized EORTC program. The European general population has a mean score of 50 with a standard deviation of 10 and the possible score range is 14−60, with higher scores indicating better cognitive functioning [Citation25].

Fatigue is the most reported symptom during cancer treatment and can significantly impact HRQoL [Citation26]; therefore, fatigue was assessed using the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI), a 20-item self-report instrument with five subscales; general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity [Citation27]. Scores range from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating more fatigue. The 75-percentile of the MFI-scale was used as a cutoff to identify patients with fatigue [Citation28].

The prevalence of depression is known to be higher among patients with cancer [Citation29], wherefore we included the major depression inventory (MDI) to investigate whether depression was a common issue among the patients in this study. The MDI is a 10-item self-report questionnaire commonly used as a diagnostic tool to measure depression [Citation30]. Total score ranges from 0 to 50 [Citation31]; a score of 0–20 indicates no depression, 21–25 mild depression, 26–30 moderate depression, and 31–50 severe depression [Citation32].

Fear of recurrence has been shown to be of high prevalence in cancer survivors and can negatively impact QoL and well-being [Citation33,Citation34]; therefore, the concerns about cancer recurrence questionnaire (CARQ-4) was included. CARQ-4 assesses fear of recurrence and consists of four items. Total score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more concern. A score of ≥12 was used as a cutoff to identify patients with high fear of cancer recurrence [Citation35].

The Decision Regret Scale (DRS) consists of five statements, assessing regret of the decision to receive adjuvant therapy [Citation36]. Final score ranges from 0 to 100, with scores >25 indicating moderate or strong regret [Citation37]. Only replies from patients starting treatment ≥6 months ago were used.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate potential selection bias, baseline characteristics for the patients responding to the questionnaire and the non-responding patients were compared using a T-test for continuous variables and Fischer’s exact test for categorical variables. To investigate the treatment periods during which patients’ HRQoL and psychological well-being were more likely to be affected by therapy, the four groups of patients depending on treatment status were compared using F-test for continuous variable and Fischer’s exact test (dichotomous variables) or χ2-test (more than two variables) for categorical variables. p Values <0.05 were considered significant. Scores from the questionnaires were calculated as described above. Patients with missing data from the questionnaire were excluded from the analyses.

Multiple linear regression analysis was used to estimate the association between selected clinical and sociodemographic factors, treatment status, and global health score from the EORTC QLQ-C30. Age was included as a linear variable. The linearity was assessed visually in scatter plots. The distribution of the regression residuals was assessed using a histogram and QQ-plot. The assumption of homoscedasticity was tested using White’s test.

Results

Study population

A total of 412 patients with melanoma who received adjuvant nivolumab and who had not experienced a relapse of melanoma after adjuvant treatment were identified and received an invitation to answer the questionnaire. Of these, 271 patients (66%) completed the questionnaire.

Comparative analysis of baseline characteristics (including sex, age, center, melanoma subtype and classification, PS, and Charlson comorbidity index) for the patients responding to the questionnaire compared to the non-responding patients showed a difference in the distribution of PS and center with more patients treated at Herlev Hospital (the Capital Region of Denmark) responding to the questionnaire (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Baseline characteristics and comparative analysis for the four groups of patients depending on treatment status are summarized in . The Charlson index was the only baseline characteristic significantly different between the groups, with more patients in active treatment for 0–6 months with Charlson comorbidity index 1 and 2, and more patients ending treatment 0–6 months ago with Charlson comorbidity index 3 and 4.

HRQoL and other aspects of mental health

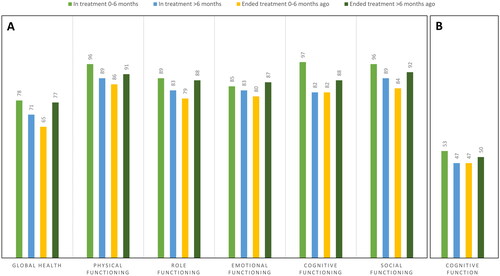

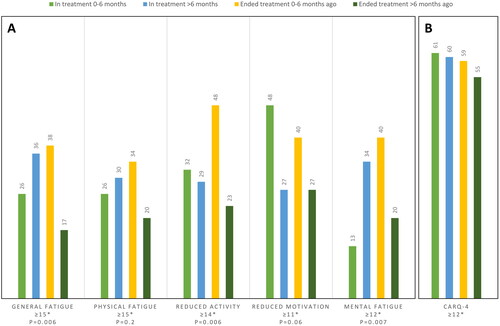

Patients in active treatment for 0–6 months generally reported higher HRQoL compared to the other treatment groups; these patients had the highest score on the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health, and physical-, role-, cognitive-, and social functioning, as well as CAT Cognitive functioning (). Compared to the patients in active treatment for 0−6 months, the patients in active treatment for >6 months had lower HRQoL with lower scores on all the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales and the CAT Cognitive functioning. The patients ending treatment 0−6 months ago had the lowest score on the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales, and the CAT cognitive functioning score was also low compared to the patients in active treatment for 0−6 months. The patients ending treatment 0−6 months ago also experienced more fatigue than the other patient groups, with most patients above the cutoff for general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, and mental fatigue in the MFI (). Compared to the patients ending treatment 0−6 months ago, the patients ending treatment >6 months ago had better HRQoL, cognitive function, and had less fatigue, with a higher mean score in all the EORTC QLQ-C30 subscales (clinically significant for global health), a higher mean score in the CAT Cognitive functioning, and fewer patients with a score above cutoff for all dimension of the MFI. For the CAT Cognitive functioning, the difference in mean scores between the four treatment groups was only minor, indicating less clinical relevance. For the MFI, the difference in the distribution of patients with a score above cutoff for the four groups were statistically significant for general fatigue, reduced activity, and mental fatigue.

Figure 1. Mean scores for the four groups of patients depending on treatment status for (A) global health and the five functioning scales from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), and (B) cognitive function from the CAT Cognitive functioning questionnaire. High score indicates better health or functioning.

Figure 2. Percent of patients with a score above cutoff (*) for the four groups of patients depending on treatment status for (A) the multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI), and (B) the Concerns About Cancer Recurrence Questionnaire (CARQ). p Values from comparison analyses of the distribution of patients with fatigue in the four groups for all subscales of the MFI are shown.

In total, 58% of patients had a CARQ-4 score above cutoff, indicating a high level of concern for cancer recurrence. The difference in the amount of patients with increased fear of recurrence between the four groups was minor.

A total of 18 patients (7%) had an MDI score >20, indicating depression of any grade; six patients had mild depression, five had moderate depression, and seven had severe depression. There were too few patients with depression to look at meaningful differences between the four groups.

Of the patients starting treatment ≥6 months before completing the questionnaire, 83% reported no or mild regret of the decision to receive adjuvant immunotherapy (). Of the patients ending treatment due to toxicity, more patients reported regretting the choice of therapy, with 57% having no or mild regret.

Table 2. Decision Regret Scale (DRS).

Factors associated with HRQoL

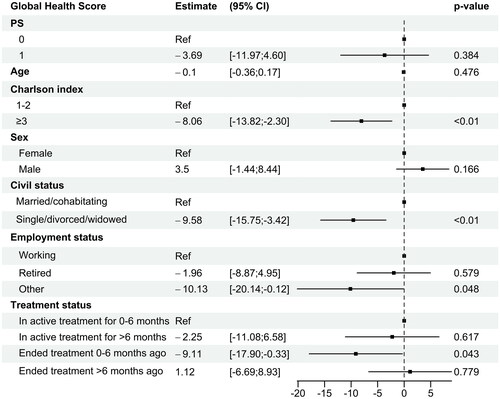

Multivariable analysis of baseline characteristics associated with global health score is shown in . Clinical and sociodemographic factors significantly associated with a low global health score, indicating poorer health, were Charlson comorbidity index ≥3 (estimate −8.1, 95% CI [−13.8; −2.3]), civil status as single, divorced, or widowed (estimate −9.6, 95% CI [−15.8; −3.4]), employment status other than working or retired (such as unemployed or currently on sick leave) (estimate −10.1, 95% CI [−20.1; −0.1]), and treatment status of recently ending therapy within the last 0−6 months (estimate −9.1, 95% CI [−17.9; −0.3]).

Discussion

In this population-based cross-sectional assessment of QoL in real-world melanoma patients, data from multiple questionnaires regarding different aspects of HRQoL and mental health indicated a temporary drop in several parameters after adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy.

Implementing anti-PD-1 therapy in the adjuvant setting increases the need for information on toxicity and QoL now treating patients, who potentially have been cured by surgery already, and who may have to live many years with the consequences of therapy. The randomized Phase 3 clinical trials leading to approval of adjuvant immunotherapy found no significant impact on HRQoL [Citation6,Citation13,Citation38]. However, these studies have strict inclusion criteria, including only a selected group of patients with good PS and few comorbidities; therefore, knowledge on QoL during adjuvant immunotherapy is limited, and there are currently no real-world data available. Also, the clinical trials assessing QoL used the EORTC QLQ-C30 as the only measure of HRQoL; however, other relevant aspects of QoL may not have been addressed, wherefore questionnaires on fatigue, depression, fear of recurrence, and regret after the decision of receiving adjuvant therapy were included to elaborate on psychological aspects of QoL.

In this study, patients with melanoma from a nationwide cohort were included, as the questionnaires were sent to all patients treated with adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy in Denmark since the introduction in 2018 until the beginning of 2021. The response rate was relatively high (66%), and there were only a few differences in baseline characteristics between the patients responding to the questionnaire and the non-responding patients; therefore, results from this study are expected to be representative of real-world patients with resected melanoma receiving adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy.

We found a tendency toward poorer health and higher levels of fatigue among the patients who ended adjuvant treatment 0−6 months ago, indicating a negative impact of adjuvant immunotherapy on HRQoL. However, patients who had been out of therapy for >6 months had better health and lower levels of fatigue, compared to patients who recently ended therapy, indicating a recovery of HRQoL over time. This tendency was observed for global health and functioning scales from the EORTC QLQ-C30, and general, physical, and mental fatigue. The drop in HRQoL after anti-PD-1 therapy hereby seems to be temporary, which is an important clinical aspect. For the CAT Cognitive functioning, the difference among the four groups was only minor, indicating no clinically relevant affection of cognitive function during therapy. When evaluating data, it must be considered that this is a cross-sectional assessment, comparing one patient at one time point with another patient at another time point; therefore, results on development in HRQoL over time should be interpreted with caution. Interestingly, despite the effect on HRQoL, most patients in this study did not regret the decision of adjuvant therapy and even among the patients ending treatment due to toxicity, more than half reported no or mild regret. In other studies, fear of recurrence has been suggested to be the most common unmet need among cancer survivors [Citation34]. Consistent with this, we also found that 58% of patients had a CARQ-4 score above cutoff, indicating a high prevalence of fear of recurrence among patient with resected melanoma receiving adjuvant immunotherapy. Furthermore, we did not find any significant difference in the amount of patients with increased fear of recurrence among the four treatment groups, indicating that fear of recurrence may be relatively constant, even after completing adjuvant therapy.

When comparing baseline characteristics for the four treatment groups, we found that more patients ending treatment within the last 0−6 months had a Charlson comorbidity index of 3−4 compared to the other groups, which must be considered when evaluating QoL. However, in multivariable analysis of baseline characteristics and treatment status, we found that the patients ending therapy within the last 0−6 months had a significantly lower global health score after adjusting for selected baseline characteristics. This supports that adjuvant treatment with ICI may affect HRQoL in real-world patients with resected melanoma, and that the influence might be temporary. Charlson comorbidity index, civil status, and employment status were also associated with global health score. The influence of these characteristics on QoL in patients with melanoma receiving immunotherapy has not been described elsewhere, but altogether, these factors may help identify patients at a greater risk of experiencing an impact on QoL and could assist in the guidance of patients.

Very little information on HRQoL during adjuvant immunotherapy is currently available, and studies on QoL for patients with advanced melanoma treated with ICI have shown mixed results. One study of long-term survivors no longer receiving ICI showed a high level of fatigue but otherwise good HRQoL with results comparable to the general population [Citation39]. This supports that a potential impact on HRQoL during treatment with ICI could be temporary. However, another study on patients previously receiving ipilimumab showed lower HRQoL and higher levels of fatigue compared to controls, indicating a continuous impact of HRQoL even after ending treatment [Citation40]. Other studies on HRQoL during treatment with ICI for patients with advanced melanoma found no clinically meaningful changes in HRQoL [Citation41,Citation42]. However, the patients in these studies had advanced diseases, and many received ipilimumab ± nivolumab, making comparison difficult.

In this study, we found a decrease in global health and fatigue, and, although the drop seems temporary, this information could be very important for both health care professionals and patients before making the decision of whether to receive adjuvant therapy. However, compared to HRQoL in general population-based surveys, the HRQoL among patients in the study was high [Citation43]. Also, we did not find any clinically significant impact of cognitive function during and after adjuvant therapy, and the incidence of depression was low, which too could be important information when considering adjuvant therapy.

Our study is conducted in a tax-paid health system with free access to medical services for all residents, excluding selection bias in the patient population, and thereby increasing the validity of our results. The most important limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design with the comparison of one patient at one time-point to another patient at another time-point, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Furthermore, when dividing patients into subgroups, our sample size became relatively smaller resulting in reduced statistical power and wide CIs in the multivariable analysis. Also, the response rate was 66%, which excludes information from one third of the eligible patients. However, when we compared participants with non-participants, we found no clinically meaningful differences in baseline characteristics. Our findings, such as the temporary drop in HRQoL, should, however, be evaluated in prospective studies.

In conclusion, adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy may affect some aspects of QoL and mental health in real-world patients, but the influence seems to be temporary. Patient characteristics, such as civil status, employment status, and comorbidity may impact HRQoL during and after treatment. This study highlights the relevance of further prospective studies on HRQoL in real-world patients to make the difficult choice of adjuvant therapy a more informed decision.

Author contributions

SP: Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project Administration; Validation; Writing-Original Draft. RBH: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing-Review & Editing. AH: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing-Review and Editing. LKT: Conceptualization; Writing-Review and Editing. KM: Formal Analysis; Writing-Review and Editing. MAP: Formal Analysis; Writing-Review and Editing. CAH: Project Administration; Resources; Writing-Review and Editing. CR: Project Administration; Resources; Writing-Review and Editing. HS: Project Administration; Resources; Writing-Review and Editing. CJ: Conceptualization; Methodology; Writing-Review and Editing. IMS: Conceptualization; Funding Acquisition; Project Administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing-Review and Editing. EE: Conceptualization; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing-Review and Editing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who participated in the survey and in DAMMED, the clinical staff recruiting patients for the survey, and the clinical and technical staff operating the DAMMED. Also, we thank Hugo Vachon from the EORTC Quality of Life Department, and Professor Bobby Zachariae for making validated questionnaires available for this analysis.

Disclosure statement

Within the last two years; CAH has received honoraria for lectures from MSD. CR has received honorarium from Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, and institutional grant for clinical trial from Helsinn Healthcare SA. CJ has received honoraria for lectures from Pfizer, Janssen, and Astellas. IMS has received honoraria for consultancies and lectures from IO Biotech, Novartis, MSD, Pierre Fabre, BMS, Novo Nordisk, TILT Bio; research grants from IO Biotech, BMS, Lytix, Adaptimmune, and TILT Bio. EE received honoraria from BMS, Pierre Fabre, Novartis for consultancies and lectures, and travel/conference expenses from MSD. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study can be made available via application to the DAMMED steering committee. Further details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Donia M, Ellebaek E, Øllegaard TH, et al. The real-world impact of modern treatments on the survival of patients with metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:25–32.

- Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-Year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535–1546.

- Long GV, Flaherty KT, Stroyakovskiy D, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in patients with metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma: long-term survival and safety analysis of a phase 3 study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1631–1639.

- Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, et al. Overall survival in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1315–1327.

- Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob J-J, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–1855.

- Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824–1835.

- Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789–1801.

- Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1813–1823.

- Mandala M, Larkin J, Ascierto PA, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab for stage III/IV melanoma: evaluation of safety outcomes and association with recurrence-free survival. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(8):e003188–9.

- Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(4):iv119–iv142.

- Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, et al. Management of Immune-Related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(36):4073–4126.

- Johnson DB, Nebhan CA, Moslehi JJ, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: long-term implications of toxicity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(4):254–267.

- Coens C, Suciu S, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Phase III trial (EORTC 18071/CA184029) of postoperative adjuvant ipilimumab compared to placebo in patients with resected stage III cutaneous melanoma: health related quality of life (HRQoL) results. Lancet Oncol. 2017;27(6):1181–1182.

- Donia M, Kimper-Karl ML, Høyer KL, et al. The majority of patients with metastatic melanoma are not represented in pivotal phase III immunotherapy trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;74:89–95.

- von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Ellebaek E, Svane IM, Schmidt H, et al. The Danish metastatic melanoma database (DAMMED): a nation-wide platform for quality assurance and research in real-world data on medical therapy in Danish melanoma patients. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;73:101943.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Fayers P, Aaronson N, Bjordal K, et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual The EORTC QLQ-C30 introduction. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Man. 2001;30:1–67.

- King MT. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(6):555–567.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144.

- Brezden CB, Phillips KA, Abdolell M, et al. Cognitive function in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(14):2695–2701.

- Falleti MG, Sanfilippo A, Maruff P, et al. The nature and severity of cognitive impairment associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Brain Cogn. 2005;59(1):60–70.

- Dirven L, Groenvold M, Taphoorn MJB, et al. Psychometric evaluation of an item bank for computerized adaptive testing of the EORTC QLQ-C30 cognitive functioning dimension in cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):2919–2929.

- Liegl G, Petersen MA, Groenvold M, et al. Establishing the European norm for the health-related quality of life domains of the computer-adaptive test EORTC CAT core. Eur J Cancer. 2019;107:133–141.

- Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, et al. Cancer-related fatigue, version 2.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(8):1012–1039.

- Smets E, Garssen B, Bonke B, et al. The multidimensional fatigue inventory (MFI); psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–325.

- Thong MSY, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Identifying the subtypes of cancer-related fatigue: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(1):38–46.

- Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer early studies of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32(32):57–71.

- Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Noteboom A, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory in outpatients. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:39–38.

- Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2001;66(2–3):159–164.

- Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2001;66(2–3):159–164.

- Koch L, Bertram H, Eberle A, et al. Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors – still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the cancer survivorship – a multi-regional population-based study. Psychooncology. 2014;23(5):547–554.

- Luigjes-Huizer YL, Tauber NM, Humphris G, et al. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2022;31(6):879–892.

- Thewes B, Zachariae R, Christensen S, et al. The concerns about recurrence questionnaire: validation of a brief measure of fear of cancer recurrence amongst Danish and Australian breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(1):68–79.

- Brehaut JC, O’Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281–292.

- Becerra-Perez MM, Menear M, Turcotte S, et al. More primary care patients regret health decisions if they experienced decisional conflict in the consultation: a secondary analysis of a multicenter descriptive study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):1–11.

- Bottomley A, Coens C, Mierzynska J, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma (EORTC 1325-MG/KEYNOTE-054): health-related quality-of-life results from a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(5):655–664.

- Mamoor M, Postow MA, Lavery JA, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of advanced melanoma treated with checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(1):e000260.

- Boekhout AH, Rogiers A, Jozwiak K, et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term advanced melanoma survivors treated with anti-CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibition compared to matched controls. Acta Oncol. 2021;60(1):69–77.

- Schadendorf D, Larkin J, Wolchok J, et al. Health-related quality of life results from the phase III CheckMate 067 study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:80–91.

- Joseph RW, Liu FX, Shillington AC, et al. Health-related quality of life (QoL) in patients with advanced melanoma receiving immunotherapies in real-world clinical practice settings. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(10):2651–2660.

- Waldmann A, Schubert D, Katalinic A. Normative data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 for the German population: a population-based survey. PLOS One. 2013;8(9):e74149–8.