Abstract

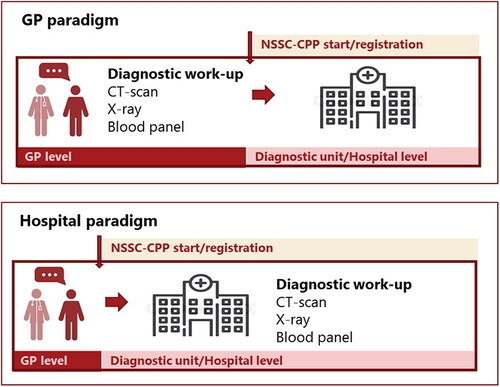

Background In Denmark, the Cancer Patient Pathway for Non-Specific Signs and Symptoms (NSSC-CPP) has been implemented with variations: in some areas, general practitioners (GPs) do the initial diagnostic work-up (GP paradigm); in other areas, patients are referred directly to the hospital (hospital paradigm). There is no evidence to suggest the most beneficial organisation. Therefore, this study aims to compare the occurrence of colon cancer and the risk of non-localised cancer stage between the GP and hospital paradigms.

Material and Methods In this registry-based case-control study, we applied multivariable binary logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios (OR) of colon cancer and non-localised stage associated with the GP paradigm and hospital paradigm. All cases and controls were assigned to a paradigm based on their diagnostic activity (CT scan or CPP) six months before the index date. As not all CT scans in the control group were part of the cancer work-up as a sensitivity analysis, we investigated the impact of varying the fraction of these, which were randomly removed using a bootstrap approach for inference.

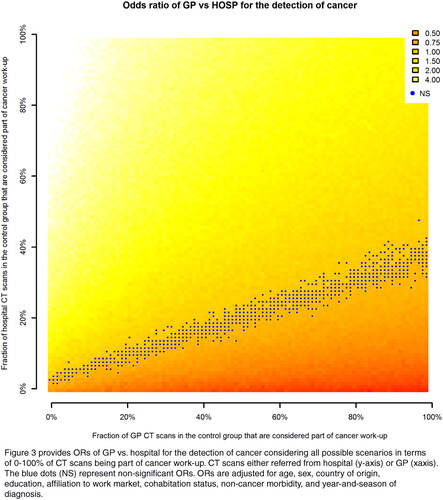

Results The GP paradigm was more likely to result in a cancer diagnosis than the hospital paradigm; ORs ranged from 1.91–3.15 considering different fractions of CT scans as part of cancer work-up. No difference was found in the cancer stage between the two paradigms; ORs ranged from 1.08–1.10 and were not statistically significant.

Conclusion Patients in the GP paradigm were diagnosed with colon cancer more often, but we cannot conclude that the distribution of respectively localised or non-localised extent of disease is different from that of patients in the hospital paradigm.

Background

In the global north, strategies such as Cancer Patient Pathways (CPPs) have been introduced to expedite the investigation, diagnosis, and initiation of treatment of individuals with potential cancer [Citation1–6]. In Denmark, CPPs were introduced in 2007 and include the patient trajectory from diagnostic work-up to potential diagnosis and initiation of treatment for the most common cancer types [Citation1]. About 50% of patients with cancer present initially with vague or non-specific symptoms, indicative of potentially severe disease but ineligible for any cancer-type specific CPPs [Citation7]. Therefore, the Cancer Patient Pathway for Non-specific Symptoms and Signs of Cancer (NSSC-CPP) was introduced in Denmark in 2012 and later with inspiration from the Danish version transferred to Norway, Sweden and UK [Citation2,Citation3,Citation8]. In Denmark, general practitioners (GPs) are gatekeepers to the secondary healthcare sector and about 70% of all NSSC-CPPs are referred by GPs [Citation9]. The initial diagnostic work-up in the NSSC-CPP consists of a diagnostic blood panel and imaging (often a CT scan). If no diagnosis is made after the initial work-up, the patient can be referred to a diagnostic unit to continue the diagnostic work-up [Citation10]. Diagnostic units are hospital clinics with comprehensive facilities for medical investigation. Of patients referred to the NSSC-CPP, about 12% turn out to have cancer and the remaining 88% do not [Citation9]. Regional and intra-regional variations have been found as in some places the initial step (diagnostic blood panel and CT scan) is performed by GPs (GP paradigm), and in others by diagnostic units (hospital paradigm) [Citation11]. The NSSC-CPP is not registered before/if patients are referred to a diagnostic unit (see ). This means that patients having their initial diagnostic work-up in general practice and who do not need further diagnostic workup in a diagnostic unit or are directed to an organ-specific CPP are not registered as taking part in an NSSC-CPP. This means that within Denmark, NSSC-CPPs do not include the same type of patients, as some have already been filtered through diagnostic work-up at GP level and others are referred directly from GP without diagnostic work-up. Thereby, registered NSSC-CPPs do not include all initiated NSSC-CPPs in Denmark. This different organisation and registration of the NSSC-CPP challenge comparing and measuring the outcomes of the GP-initiated NSSC-CPP (GP paradigm) and the hospital-initiated NSSC-CPP (hospital paradigm) across the country. Therefore, no evidence suggests whether the GP paradigm is associated with better prognostic outcomes than the hospital paradigm or vice versa.

To compare the two paradigms, we included patients with a colon cancer diagnosis (cases) and corresponding controls and identified whether their initial diagnostic steps were initiated by GPs (GP paradigm) or hospitals (hospital paradigm). We focussed on colon cancer as colon cancer often presents with non-specific symptoms and is one of the most common cancers diagnosed within the NSSC-CPP [Citation12,Citation13]. Thereby, the aim of this study was to compare the occurrence of colon cancer between the GP paradigm and the hospital paradigm and given a colon cancer diagnosis, to compare the risk of non-localised cancer stage between the two paradigms. Thereby, we assumed the stage at diagnosis is a surrogate outcome for patient prognosis within the NSSC-CPP.

Method

Study design

This study was a matched case-control study and included individual-level registry data obtained by linking Danish national registers using the unique personal identification number assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration [Citation14].

Study population

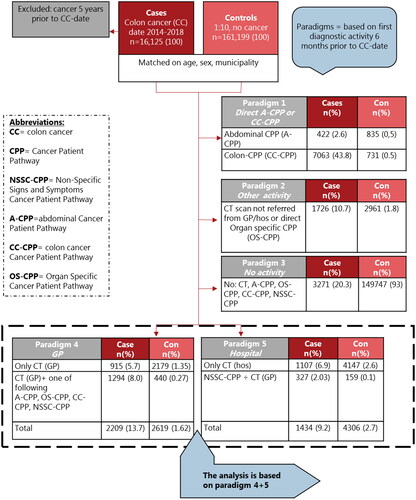

Cases were all patients ≥18 years diagnosed with colon cancer from 2014–2018 (inclusive) in the Danish Cancer Registry [Citation15]. Ten controls per case (1:10) were matched on age, sex and the municipality of residence, and controls were free of colon cancer on the date of diagnosis of cases (index-date). We excluded all cases and potential controls diagnosed with any cancer (except for non-melanoma skin cancer) five years prior to the index-date. Further, we excluded individuals if they had immigrated to or emigrated from Denmark six months prior to the index-date.

Paradigms

In this study, we were interested in comparing patients initiating diagnostic work-up for suspected cancer based on non-specific symptoms referred either from GP or hospital. Therefore, we needed to differentiate between patients with different routes to diagnosis. To make this distinction while at the same time not having information on symptoms at referral, all cases and controls were assigned to a paradigm based on their first diagnostic activity six months prior to the index-date as registered in the Danish National Patient Registry. Diagnostic activity included: CT scan, colon cancer CPP (CC-CPP), abdominal CPP (A-CPP) (including a list of CPPs related to the abdomen, Supplementary 1), other organ-specific CPPs (OS-CPP), and the NSSC-CPP (). These were chosen as they are relevant markers for cancer diagnostic work-up. Paradigm 1 includes patients directly referred to a colon CPP or a CPP related to the abdomen. We hypothesised that this group of CPPs might be initiated based on alarm symptoms of cancer, related to the abdomen, though not initiated based on non-specific symptoms. Paradigm 2 included patients with other CPPs and CT scans not referred from GP or hospital including a mixed group of patients referred from other health professionals such as dentists, medical specialist clinics and institutions such as prisons etc. Paradigm 3 included cases and controls with no CT scans, NSSC-CPPs or CPPs before index-date. Paradigm 4 (GP paradigm) and 5 (hospital paradigm) included cases and controls with diagnostic activity initiated by GP or hospital respectively, and only these paradigms were included for analysis within this study. The GP paradigm included either a CT scan referred by GP or a CT scan referred by GP plus one of the following: A-CPP, OS-CPP, CC-CPP, NSSC-CPP. The hospital paradigm included either a CT scan referred by the hospital or an NSSC-CPP. The hospital paradigm was narrower in its inclusion criteria than the GP paradigm, because we did not want to include patients who after a hospital-initiated CT scan were sent to either A-CPP, OS-CPP or CC-CPP as we hypothesised that these might be referred based on alarm symptoms, thereby belonging to paradigm 1.

Outcomes

The outcomes were the occurrence of colon cancer (ICD-10 diagnosis code C18). As a proxy for the stage at a diagnosis the colon cancer cases were categorised as localised, non-localised and undefined extend of disease as described elsewhere [Citation16] between 2014–2018, obtained from the Danish Cancer Registry based on tumour, node, metastases (TNM) codes (Supplementary 2) [Citation15].

Covariates

Sex, age and country of origin were obtained at index-date from the Population Register [Citation17]. Educational level came from the Danish Education Register [Citation18], Affiliation to the labour market from the Danish Registry of Labour Market Affiliation [Citation19], and cohabitation status from the Danish Family Relations Database [Citation17,Citation20]. Non-cancer morbidity was based on twenty broad diagnostic groups of chronic diagnoses [Citation21] identified in the National Patient Registry [Citation22]. This measure was chosen as it has been developed specifically to identify comorbidity in patients with cancer. It includes a broad range of diseases while still being restrictive regarding ‘isolated’ diseases and risk factors such as hypertension [Citation21].

Statistical analysis

The two main analyses were: (1) the assessment of a difference in colon cancer incidence between the GP and the hospital paradigms, and (2) the assessment of a difference in the incidence of non-localised cancer relative to localised cancer between the two paradigms. Paradigms were considered the exposure variable in both analyses and the incidence of colon cancer and stage at a diagnosis were the outcome variables of each analysis respectively. Odds ratios (ORs) from multivariable binary logistic regression models were used for the comparisons, where, due to the symmetry of the OR, the binary paradigm (GP or hospital) functioned as an outcome, and the four-category stage variable (localised, non-localised, undefined, no cancer) functioned as exposure; for the latter analysis, the OR between non-localised and localised were reported. Uncertainty estimates were obtained from the empirical bootstrap distribution of the effect estimates, which involved resampling the original data set with the replacement of matched sets 1999 times. All effect estimates were adjusted for age, sex, country of origin, education, affiliation to labour market, cohabitation status, non-cancer morbidity, and year and season of diagnosis.

In the definition of the paradigms, we excluded CT scans that were likely to be unrelated to cancer diagnostics such as the knee, hand, ankle, etc. A full list is described elsewhere [Citation12]. However, since CT scans are used for many purposes, we cannot assume that all the remaining CT scans were part of the diagnostic process; nor is this information listed in the Danish registers. We assumed that in the GP and hospital paradigms a fraction of the scans not accompanied by a CPP in the control group were not part of cancer diagnostics. CT scans in the case group and CT scans occurring together with a CPP were assumed to be part of cancer diagnostics.

To investigate the sensitivity of our analyses with respect to the assumed fraction, and to illustrate the range of possible results, we performed a sensitivity analysis. In this, analyses for all 101 × 101 = 10,201 possible choices of fractions from 0% to 100% were calculated, each based on a single bootstrap replicate. Inquiry at GP practices in two Danish Regions and two radiological departments proposed that 70–90% of all CT scans ordered, both by GPs and hospitals, were part of cancer diagnostics. For CT scans not accompanied by a CPP in the control group, this translated into 63.7–87.9% for the GP paradigm, and 68.7–89.6% for the hospital paradigm (for calculation see Supplementary 3).

Results

Cohort characteristics

There were 16,125 cases and 161,199 matched controls (). Of cases, 6186 (38%) were diagnosed with colon cancer in the localised stage; 6719 (42%) in non-localised stage, and 3220 (20%) with an undefined stage. The control group more often had no diagnostic activity before index-date, were more often non-western descent and had fewer comorbidities than colon cancer cases. The undefined cases were in general older patients with more comorbidities and were more often retired than the other groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of the total study population consisting of cases and matched controls (n = 177,324).

Odds of cancer between paradigms (analysis 1)

Patients in the GP paradigm were more likely to receive a diagnosis of cancer than patients in the hospital paradigm. This analysis was sensitive to the assumptions on fractions of CT scans being part of cancer diagnostics, as the adjusted ORs ranged from 1.91 (95% CI 1.73–2.11) to 3.15 (2.85–3.47) (, ). The highest OR was estimated under the assumption that more CT scans from the hospital were part of cancer diagnostics (90%) and fewer from GPs (70%).

Table 2. Odds ratios of GP versus hospital paradigms for detection of cancer (analysis 1) and stage at diagnosis (analysis 2) under different assumptions regarding the fraction of CT scans being part of cancer work-up.

Stage at colon cancer diagnosis between paradigms (analysis 2)

No difference was found in cancer stage between the GP and hospital paradigms; ORs ranged from 1.08 (0.90–1.29) to 1.10 (0.92–1.32), meaning that patients in the GP paradigm were slightly more likely to be diagnosed in a non-localised stage. However, none of the ORs was statistically significant and the analysis was not sensitive to assumptions on fractions of CT scans being part of cancer diagnostics ().

provides ORs of GP vs. hospital for the detection of cancer considering all possible scenarios in terms of 0–100% of CT scans being part of a cancer work-up. CT scans are either referred from the hospital (y-axis) or GP (x-axis). The blue dots (NS) represent non-significant ORs. ORs are adjusted for age, sex, country of origin, education, affiliation to the work market, cohabitation status, non-cancer morbidity, and year and season of diagnosis.

Discussion

Summary

Patients whose initial diagnostic work-up took place in general practice (GP paradigm) had 2-3 times higher odds of receiving a diagnosis of colon cancer than people whose initial diagnostic work-up took place in a hospital (hospital paradigm). Depending on perspective, this finding can be interpreted in different ways. It might reflect the essential role of GPs in cancer diagnostics [Citation23–26] and suggests that when GPs initiate a diagnostic work-up and order a CT-scan, their suspicion of colon cancer is more often confirmed compared to when initiated by hospitals. The finding could also be interpreted as GPs referring too few patients for diagnostic work-up, or the hospital too many because the GPs referrals are associated with higher odds of colon cancer. One could argue that the ‘hit-rate’ (fraction of referrals that end in a cancer diagnosis) in the GP paradigm is too high and should be reduced by referring more people. However, there is no evidence suggesting an appropriate threshold for such a hit rate. Referring more patients to diagnostic work-up of cancer risks introducing harms, e.g., complications to downstream procedures, overdiagnosis, overtreatment and thereby physical and psychosocial consequences [Citation27,Citation28]. More studies are needed to estimate the magnitude of these potential risks. For patients with colon cancer, we found slightly higher, albeit non-significant, odds for non-localised cancer stage in the GP paradigm. Therefore, from a patient prognostic perspective, it does not seem as though patients who initiate their diagnostic work-up in the GP paradigm are better or worse off than patients in the hospital paradigm. Still, this finding must be interpreted with caution due to the design of this study.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the large dataset from high-quality validated Danish registers in which we were able to link information about cancer stage at diagnosis and diagnostic activity. No other study has examined the stage at diagnosis while investigating different paradigms of initial cancer work-up in Denmark. When designing this study, we knew we would include people with a CT scan that was likely to be unrelated to cancer work-up, thus, strength is the presentation of ORs under a range of different assumptions. Due to organisational variations of the NSSC-CPP in Denmark, patients having their initial diagnostic work-up in general practice are not labelled – NSSC-CPP, but those starting their diagnostic workup in a diagnostic unit at the hospital are. Therefore, to identify these two populations and later compare them, we cannot use the label – NSSC-CPP. Regardless of organisational structure most of the patients with non-specific symptoms of cancer are having a CT scan as part of the initial diagnostic work-up. Therefore, CT scan was used as a marker to identify the population of interest for this study. Still, some patients with non-specific symptoms do not have a CT scan but might have an alternative test such as a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), however, not included in the analysis. However, as long as no sufficient registration of the GP-initiated diagnostic work-up exists, we suggest the CT scan as the best marker for initiation of diagnostic work-up as it is the most often used test within the NSSC-CPP setting and recommend by guidelines [Citation10].

We included the GP and hospital paradigm, only, as these were the patients of interest. Still, the five paradigms are not independent of each other. Therefore, we cannot fully exclude differing case-mix within this study. Still, we are aware of this limitation and did comprehensive work in developing operational definitions of different paradigms to include only the patients of interest within the analysis, namely those in paradigms 4 and 5. For transparency, we have described all five defined paradigms.

For 20% of cases, information about the stage of colon cancer diagnosis was missing and the group with an undefined cancer stage was associated with advanced age and morbidity. While we adjusted for these variables, we cannot exclude that they biased the results. Finally, we dichotomised the stage at diagnosis into localised (stage 1–2) and non-localised stages (regional or distant spread, stage 3–4). Clinically, this dichotomisation is, however, not optimal, as it would have been relevant to divide into stages 1–3 and stage 4 as a proxy for potentially curative and non-curative possibilities for treatment, respectively. This was, however, not possible due to the data available in the period in the Danish Cancer Registry. Still, we regarded the available data on stage at diagnosis as essential to estimate a surrogate outcome for patient prognosis.

Comparison with existing literature

Despite the fact that the NSSC-CPP runs differently across Denmark, we have not identified any other studies investigating the effect of different diagnostic paradigms for patients with non-specific symptoms. A Danish matched cohort study by Naeser and colleagues found that patients with cancer of all types presenting with non-specific symptoms did not have a worse prognosis than patients with cancer diagnosed through other routes [Citation29]. The authors suggested that GPs referred patients in a timely way to the diagnostic units as similar mortality rates were observed between the different routes to diagnosis [Citation29,Citation30]. A population-based study of patients with cancer of all types in Denmark investigated the association between the route to diagnosis and one-year all-cause mortality [Citation31]. Patients diagnosed through a hospital-initiated CPP were slightly more likely to die within the first year compared to patients diagnosed through GP-initiated CPPs (OR 1.09 (95% CI 1.04–1.14)) [Citation31]. These results also indicate that patients referred by GPs do not appear to have a worse prognosis than patients referred by hospitals. The risk of confounding by severity needs to be considered as there might be an association between disease severity and route to diagnosis. In our study, we tried to reduce this bias when we defined the GP and hospital paradigms: we hypothesised that patients with advanced disease were more often directly referred to an abdominal CPP and were therefore not included in the analysis. However, even though we considered this confounding factor we cannot fully discard it as a potential explanation, at least in part. CT scans are often part of cancer work-up in patients with non-specific symptoms [Citation12,Citation32,Citation33]. However, due to the registration practice in Denmark, we were unable to distinguish between CT scans being part of cancer diagnostic and CT scans ordered for other purposes. Being able to make this distinction would further enable interesting comparisons between the proportion of CT-scans as part of the diagnostic process in GP and hospitals and the risk for diagnosing cancer. Hypothetically, similar organisational variations of the NSSC-CPP might exist in Sweden as no studies have examined all diagnostic sites within the country [Citation34–36]. In UK, different versions of the NSSC-CPPs have been introduced but also here variations in registration and practice challenge the monitoring and recommendation of best practices [Citation37,Citation38]. Thereby, our findings might be relevant in an international setting.

Implications for research and practice

There may be concerns that patients receiving initial diagnostic work-up in general practice do not receive the same high-quality cancer work-up if they do not receive fast-track referrals to a diagnostic unit. Our results indicate that patients might not be worse off by starting their cancer work-up in general practice. As we found that relatively more patients were diagnosed with cancer in the GP paradigm, this study also points to important discussions about the threshold for referring patients to diagnostic work-up in order to balance the benefits and harms of diagnostic workup. Our study suggests that a low hit rate of cancer should not represent a successful diagnostic work-up alone. Further, our findings raise the question of which outcomes should be considered to adequately measure the effectiveness of the NSSC-CPP and how. In this study, we included disease extension at diagnosis because we considered the patients’ prognostic perspectives essential when striving to compare the effect, and thereby the quality, of the different paradigms. Other important outcomes have not been investigated. From an economic perspective, the initial cancer work-up might be more cost-effective if performed in general practice. Patient and GP preferences could also be included when deciding how the NSSC-CPP should be organised. It might be less invasive and more convenient for patients to start cancer work-up in general practice, but GPs might also need the option to fast-track patients for diagnostic work-up in the hospital. Research using both quantitative and qualitative methods could explore and contrast suggested alternatives.

The present study’s findings are important for policymakers as they indicate the challenge in measuring and comparing the outcomes of the NSSC-CPP. Thereby, we do not know if the introduction of the NSSC-CPP has the intended effect. Especially, the initial diagnostic work-up in general practice was not registered as part of the NSSC-CPP making these patients difficult to track in the Danish registries. Such registration is needed if future studies should be more valid in estimating outcomes across paradigms. For some time, there has been political and media attention in Denmark on the importance of ensuring that patients receive uniform cancer work-up and treatment across the country. Uniformity risks implementing a less prognostically beneficial diagnostic model, as the evidence regarding the outcomes of the current NSSC-CPP remains limited. Findings from this study should be interpreted with caution: other cancers may display different patterns. We focussed on colon cancer as this is one of the most common cancers detected through the NSSC-CPP [Citation12,Citation13]. Further, overdiagnosis of colon cancer is limited and thus length time bias is reduced [Citation28]. Future studies could replicate our study design to include other cancer types to validate and add to our findings.

Conclusion

In this population-based matched case-control study, we found that a larger proportion of patients in the GP paradigm were diagnosed with colon cancer compared to the hospital paradigm. As the estimates on differences between localised versus non-localised stages in the two paradigms were small and statistically non-significant, we were unable to conclude that patients who initiate their cancer work-up in general practice have a better or worse cancer prognosis than patients whose work-up is initiated from the hospital. These findings should be interpreted with caution as the study demonstrates the challenge of measuring the outcomes of the NSSC-CPP in Denmark and that the different routes to diagnosis might not explain cancer prognosis within this population.

Ethical approval

In agreement with the General Data Protection Regulation, this study is registered by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal 514-0465/20-3000). According to Danish legislation, a register-based study with no contact with individuals does not require informed consent or Ethical Board review. The report follows the STROBE reporting guideline for observational studies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (259.3 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the GPs and radiologists that contributed knowledge about the purpose and use of CT scans in Denmark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Denmark Statistics and the Danish Cancer Registry, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Danish Health Authority [Internet]. Aftale om gennemførelse af målsætningen om akut handling og klar besked til kræftpatienter [Agreement on implementation of aim of urgent action and clear message to patients with cancer]; 2007. [cited 2020 Sep 21]. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Viden/Kraeft/Kr%C3%A6ftpakker/Historisk-overblik/Aftale-om-akut-handling-og-klar-besked.ashx?la=da&hash=E694D3DCC6869C5F912A660EBBBD7629C2643E6E.

- Helsedirektoratet [Internet]. diagnostisk-pakkeforlop-for-pasienter-med-uspesifikke-symptomer-pa-alvorlig-sykdom-som-kan-vaere-kreft [The Norwegian directorate of health. Cancer patient pathway for patient with non specific signs and symptoms of cancer]; 2019 [cited 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/pakkeforlop/diagnostisk-pakkeforlop-for-pasienter-med-uspesifikke-symptomer-pa-alvorlig-sykdom-som-kan-vaere-kreft/inngang-til-pakkeforlop-for-pasienter-med-uspesifikke-symptomer.

- Cancercentrum [Internet]. Allvarliga ospecifika symtom som kan bero på cancer Standardiserat vårdförlopp [Serious non specific symptoms that can be cancer. Standardised cancer patient pathways]; 2018. [cited 2019 Nov 21]. Available from: https://www.cancercentrum.se/globalassets/vara-uppdrag/kunskapsstyrning/varje-dag-raknas/vardforlopp/kortversioner/pdf/kortversion-svf-allvarliga-ospecifika-symtom-cancer.pdf.

- Prades J, Espinàs JA, Font R, et al. Implementing a cancer fast-track programme between primary and specialised care in Catalonia (Spain): a mixed methods study. Br J Cancer. 2011; 105(6):753–759.

- National Health Service UK [Internet]. The NHS Cancer Plan. A plan for investment. A plan for reform; 2000. [cited 2022 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.thh.nhs.uk/documents/_Departments/Cancer/NHSCancerPlan.pdf.

- New Zealand Ministry of Health [Internet]. Suspected cancer in primary care: guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities; 2009. [cited 2022 Apr 27]. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/suspected-cancer-primary-care-guidelines-investigation-referral-and-reducing-ethnic-disparities.

- Bislev LS, Bruun BJ, Gregersen S, et al. Prevalence of cancer in Danish patients referred to a fast-track diagnostic pathway is substantial. Danish Med J. 2015; 62(9):1–5.

- Nicholson BD, Oke J, Friedemann Smith C, et al. The suspected cancer (SCAN) pathway: protocol for evaluating a new standard of care for patients with non-specific symptoms of cancer. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018168–8.

- Danish Health Data Authority [Internet]. Diagnostic pathway for serious disease 1 January 2017–30 June 2018; 2019 [cited 2021 May 5]. Available from: https://sundhedsdatastyrelsen.dk/-/media/sds/filer/find-tal-og-analyser/sygdomme-og-behandlinger/alvorlig-sygdom_diagnostisk-pakkeforlob/diagnostiske-pakkeforloeb-2017_2018.pdf.

- Danish Health Authority [Internet]. Diagnostisk pakkeforløb [diagnostic pathway]. Copenhagen: Danish Health Authority; 2022. [cited 2022 Apr 24]; Available from: https://www.sst.dk/da/Udgivelser/2022/Diagnostisk-pakkeforloeb

- Damhus CS, Siersma V, Dalton SO, et al. Non-specific symptoms and signs of cancer: different organisations of a cancer patient pathway in Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021; 39(1):23–30.

- Damhus CS, Siersma V, Birkmose AR, et al. Use and diagnostic outcomes of cancer patient pathways in Denmark – is the place of initial diagnostic work-up an important factor? BMC Health Serv Res. 2022; 22(1):130.

- Næser E, Fredberg U, Møller H, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk of serious disease in patients referred to a diagnostic centre: a cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017; 50(Pt A):158–165.

- Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549.

- Gjerstorff ML. The Danish cancer registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011; 39(7 Suppl):42–45.

- Skriver C, Dehlendorff C, Borre M, et al. Use of low-dose aspirin and mortality after prostate cancer diagnosis: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019; 170(7):443–452.

- Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011; 39(7 Suppl):22–25.

- Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011; 39(7 Suppl):91–94.

- Petersson F, Baadsgaard M, Thygesen LC. Danish registers on personal labour market affiliation. Scand J Public Health. 2011; 39(7 Suppl):95–98. .

- Statistic Denmark [Internet]. Households and families Denmark: statistic Denmark; 2022. [cited 2022 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/borgere/husstande-familier-og-boern/husstande-og-familier.

- Loeppenthin K, Dalton SO, Johansen C, et al. Total burden of disease in cancer patients at diagnosis-a Danish nationwide study of multimorbidity and redeemed medication. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(6):1033–1040.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490.

- Smith CF, Kristensen BM, Andersen RS, et al. GPs’ use of gut feelings when assessing cancer risk: a qualitative study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(706):e356–e363.

- Friedemann Smith C, Moller Kristensen B, Sand Andersen R, et al. GPs’ use of gut feelings when assessing cancer risk in primary care: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(706):.

- Smith CF, Drew S, Ziebland S, et al. Understanding the role of GPs’ gut feelings in diagnosing cancer in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing evidence. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(698):e612–e621.

- Holtedahl K, Vedsted P, Borgquist L, et al. Abdominal symptoms in general practice: frequency, cancer suspicions raised, and actions taken by GPs in six European countries. Cohort study with prospective registration of cancer. Heliyon. 2017; 3(6):e00328.

- Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Jr., Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. Jama. 2013; 310(8):797–798.

- Glasziou PP, Jones MA, Pathirana T, et al. Estimating the magnitude of cancer overdiagnosis in Australia. Med J Australia. 2020;212(4):163–168.

- Næser E, Møller H, Fredberg U, et al. Mortality of patients examined at a diagnostic Centre: a matched cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018; 55:130–135.

- Naeser E. Diagnosis, clinical assesment and prognosis in patients with non-specific serious symptoms [dissertation]. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University; 2017.

- Danckert B, Falborg AZ, Christensen NL, et al. Routes to diagnosis and the association with the prognosis in patients with cancer – a nationwide register-based cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021; 74:101983.

- Moseholm E, Lindhardt BO. Patient characteristics and cancer prevalence in the Danish cancer patient pathway for patients with serious non-specific symptoms and signs of cancer – a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;50(Pt A):166–172.

- Møller M, Juvik B, Olesen SC, et al. Diagnostic property of direct referral from general practitioners to contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal CT in patients with serious but non-specific symptoms or signs of cancer: a retrospective cohort study on cancer prevalence after 12 months. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(12):e032019–7.

- Stenman E, Palmér K, Rydén S, et al. Diagnostic center for primary care patients with nonspecific symptoms and suspected cancer: compliance to workflow and accuracy of tests and examinations. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2021;39:(2):148–156.

- Stenman E, Palmer K, Ryden S, et al. Diagnostic spectrum and time intervals in Sweden’s first diagnostic center for patients with nonspecific symptoms of cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019; 58(3):296–305.

- Sundquist J, Palmér K, Rydén S, et al. Time intervals under the lens at Sweden’s first diagnostic center for primary care patients with nonspecific symptoms of cancer. A comparison with matched control patients. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1–10.

- Chapman D, Poirier V, Vulkan D, et al. First results from five multidisciplinary diagnostic Centre (MDC) projects for non-specific but concerning symptoms, possibly indicative of cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:(5):722–729.

- ACE. Key messages from the evaluation of multidisciplinary diagnostic centres (MDC): a new approach to the diagnosis of cancer. 11th ed. UK: Cancer Research UK; 2019. p. 13.