Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is the most prevalent neoplasm in women in North American and European countries. Data about intensive care unit (ICU) requirements and the related outcomes are scarce. Furthermore, long-term outcome after ICU discharge has not been described.

Material and methods

We conducted a retrospective monocenter study including patients with breast cancer requiring unplanned ICU admission over a 14-year period (2007–2020).

Results

177 patients (age = 65[57–75] years) were analyzed. Breast cancer was at a metastatic stage for 122 (68.9%) patients, recently diagnosed in 25 (14.1%) patients or in progression under treatment in 76 (42.9%) patients. Admissions were related to sepsis in 56 (31.6%) patients, to iatrogenic/procedural complication in 19 (10.7%) patients and to specific oncological complications in 47 (26.6%) patients. Seventy-two (40.7%) patients required invasive mechanical ventilation, 57 (32.2%) vasopressors/inotropes, and 26 (14.7%) renal replacement therapy. In-ICU and one-year mortality rates were 20.9% and 57.1%, respectively. Independent factors associated with in-ICU mortality were invasive mechanical ventilation and impaired performance status. One-year mortality in ICU survivors was independently associated with specific complications, triple negative cancer, and impaired performance status. After hospital discharge, most patients (77.4%) were able to continue or initiate antitumoral treatment.

Conclusion

ICU admission was linked to the underlying malignancy in one-quarter of breast cancer patients. Despite the low in-ICU mortality rate (20.9%) and thereafter continuation of cancer treatment in most survivors (77.4%), one-year mortality reached 57.1%. Impaired performance status prior to the acute complication was a potent predictor of both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Background

Breast cancer is the most prevalent neoplasm in women in North American and European countries [Citation1]. One in eight to ten women will have breast cancer during their lifetime and breast cancer accounts as the leading cause of death by cancer in the vast majority of countries [Citation2]. Recent data indicated the increasing incidence of breast cancer while the death rate dropped by 42% since 1989 in the United States [Citation1]. In Europe, breast cancer-related mortality rates declined from 17.9/100,000 in 2002 to 15.2/100,000 in 2012, with a predicted 2020 rate of 13.4/100,000 [Citation3].

The risk of intensive care unit (ICU)-admission within two years after a cancer diagnosis is low [Citation4]. However, with respect to the high prevalence of this neoplasm, it is noteworthy that breast cancer accounts for a high proportion of neoplasms in unselected cohorts of critically ill patients with solid tumors and breast cancer is the most frequent tumor among metastatic solid cancer patients admitted to the ICU [Citation5,Citation6].

Despite the high frequency of this malignancy, very few studies described this population in the intensive care. Data about ICU requirements and the related characteristics and outcomes are scarce. Furthermore, long-term mortality after ICU discharge and the related prognostic factors have not been specifically described, including whether or not life-threatening complications may impact on the initiation or continuation of antitumoral treatment after hospital discharge [Citation7,Citation8].

The objectives of our study were to analyze the characteristics and outcomes of breast cancer patients admitted to the ICU for a medical reason.

Material and methods

Patients

We conducted a retrospective monocenter study between 2007 and 2020 including consecutive adult patients with breast cancer requiring unplanned admission to a 24-bed medical ICU located in a tertiary care hospital. Patients admitted after elective or emergency surgical procedures are managed in a different surgical ICU. Non-inclusion criteria were the following: patients with cancer cured for more than 5 years, planned admissions following elective surgery, and admission to secure a procedure. Only the first ICU stay was analyzed when patients had multiple ICU admissions.

Data collection

The following characteristics of breast cancer were collected: date of diagnosis, staging (localized, advanced, metastatic), oncologic status according to RECIST (partial response including stable disease, complete remission, progression, newly diagnosed during ICU stay or within one month before ICU admission) and treatment within three months prior to ICU admission (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, targeted therapy including trastuzumab, pertuzumab, bevacizumab, lapatinib, erlotinib, sacituzumab-govitecan, atezolizumab and palbociclib) [Citation9]. Performance status was measured according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale. With regard to characteristics of the ICU stay, the following variables were collected: the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at ICU admission to estimate the initial severity, organ failure supports including invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, vasopressors/inotropes support and renal replacement therapy were collected [Citation10]. Leukopenia at admission was defined as leukocyte count < 1000/mm3. Decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapies (DFLST) (either withholding or withdrawing therapy) were collected. ICU admissions patterns were distributed into non-specific complications (i.e., infection, bleeding, ischemic event, venous thrombo-embolism), drug-related and procedural adverse events, and specific oncological complications directly related to breast cancer (i.e., hypercalcemia, pleural effusion, lymphangitis carcinomatosis, brain metastasis or carcinomatous meningitis, pericardial effusion, bleeding metastasis, superior vena cava syndrome, thrombotic microangiopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, tumor lysis syndrome, digestive tract compression or malignant liver infiltration). Some patients were part of a cohort of critically cancer patients with solid tumors already reported elsewhere [Citation11].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median [interquartile range] and categorical variables as counts (percentages). The main outcomes were in-ICU and one-year mortality. Independent predictors of in-ICU and one-year mortality (available for n = 170 (96%) patients for the latter) were addressed using a cause-specific multivariate Cox regression analysis. The model included variables that reached a p value of less than .20 in univariate analysis. The decision to forgo life-sustaining therapy was not included in the ICU-survival analysis to avoid immortality time bias and because of the self-fulfilling prophecy risk. All tests were two-sided. p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis were carried out using R 3.5.3 and R Studio (R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria).

Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics committee from the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française (CE SRLF 17-03) which waived the need for signed consent according to French regulations.

Results

Characteristics of patients

The study included 177 patients (98.9% women with a median age of 65 [57–75] years), representing 9.6% of cancer patients admitted to the ICU during the study period (). The time between cancer diagnosis and ICU admission was 3 [1–9] years. Breast cancer was at a metastatic stage in 122 (70.1%) patients. The malignancy was newly diagnosed for 25 (14.4%) patients, in partial response for 43 (24.7%) patients, and in progression for 76 (43.7%) patients. Within the last three months, 77 (43.5%) patients had received chemotherapy, 26 (14.7%) had received targeted therapy and 16 (9.0%) had undergone radiotherapy. Baseline performance status prior to the acute complication was severely impaired (score 3 or 4) in 33 patients (18.6%). No major differences but the progression status were observed between patients admitted before and after 2013 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

Characteristics of ICU stay

Seventy-five patients (42.4%) were admitted because of non-specific complications, mainly infection (n = 56, 31.6%) and thrombo-embolic events (n = 6, 3.4%) (). Eight patients (8.4%) exhibited leukopenia at admission. Forty-seven patients (26.6%) were admitted because of specific complications, mainly pleural effusion (n = 10, 5.6%), hypercalcemia (n = 10, 5.6%), neurological complications (n = 5, 2.8%) and thrombotic microangiopathy (n = 4, 2.3%). Drug-related and procedural adverse events accounted for 11 (6.2%) and 8 (4.5%) admissions. The median SOFA score at admission was 5 points [4–8]. Seventy-two (40.7%) patients required invasive mechanical ventilation, 57 (32.2%) vasopressors or inotropes, and 26 (14.7%) renal replacement therapy during the ICU stay.

Table 2. Intensive care unit characteristics and outcomes.

Outcomes and prognosis factors

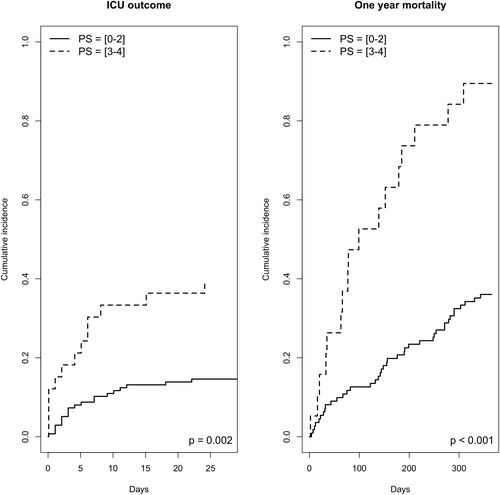

The in-ICU mortality rate of the whole cohort was 20.9%, and the one-year mortality rate was 57.1% in the 170 patients with complete follow-up. In multivariate analysis, factors associated with ICU-mortality were invasive mechanical ventilation (cause-specific hazard (CSH) 2.53 [1.11–5.75], p = .03) and poor performance status (3 or 4) (CSH 2.37 [1.18–4.80], p = .02). One-year mortality in ICU-survivors was independently associated with specific complications (CSH 2.20 [1.31–3.71], p = .003), triple-negative cancer status (CSH 1.97 [1.06–3.67], p = .03) and poor performance status (CSH 1.51 [1.19–1.92], p < .001). Short-term and one-year vital status according to performance status are displayed in . The one-year mortality rate was 88.9%, 54.5%, and 38.9% in the triple negative, hormone receptors positive, and HER2 positive cancer, respectively. The features of anti-tumoral treatment after hospital discharge could be obtained for 84 of 96 ICU survivors previously treated with antitumoral treatment or newly diagnosed. Antitumoral treatment was continued for 65 of them (77.4%), discontinued because of non-indication for 8 of them (9.5%), and discontinued despite indication for 11 (13.1%) of them.

Figure 1. Short-term and one-year survival status according to performance status. Twenty eight day mortality was assessed according to performance status 0–1–2 vs. 3–4. The landmark is set at the time of ICU admission. One-year mortality was assessed in ICU-survivors according to performance status 0–1–2 vs. 3–4. The landmark is set at the time of ICU discharge.

Discussion

Therapeutic advances including chemotherapy and targeted therapy have allowed dramatic improvements in the prognosis of breast cancer, even at the metastatic stage [Citation1]. This study provides an original focus on the characteristics and prognosis of critically ill breast cancer patients, mostly with advanced malignancies at a metastatic stage.

It is noteworthy that ICU admission was related to specific oncological complications in one-quarter of patients. Four in 5 patients survived the ICU-stay, but more than half died within the next year. Performance status prior to the acute complication appears to be a relevant short- and long-term prognosis factor in this population.

Breast cancer accounts for 1 in 4 cancer cases and for 1 in 6 cancer deaths among women. As a matter of fact, the present cohort comprised a high proportion of patients with advanced malignancies, including two-thirds at a metastatic stage.

Apart from usual suspects like infection or thrombo-embolic events, ICU admission was driven by the underlying malignancy in one in three patients, because of specific complications such as hypercalcemia, pleural effusion, neurological complication or thrombotic microangiopathy or because of adverse events secondary to antitumoral drug or to procedures performed as part of cancer treatment. Clinicians should therefore keep a high level of suspicion for such complications in case of a life-threatening event and promptly initiate an appropriate diagnostic work-up.

Four out of 5 patients survived the ICU stay. Destrebecq et al. reported a 15% ICU-mortality in a population suffering from less severe complications requiring fewer organ failure supports [Citation12]. Compared to other neoplasms, breast cancer is associated with higher in-hospital survival after an ICU admission [Citation13]. Another study even reported similar ICU-survival rates when comparing breast or gynaecological cancer patients to non-cancer patients [Citation14]. Those encouraging results support a broad admission policy for this population even at a metastatic stage and should refute the perception of impaired prognosis to prevent an unjustified reluctance to advanced life supports [Citation15,Citation16].

Importantly, cancer characteristics did not determine short-term prognosis, as reported elsewhere in larger cohorts of solid cancer patients in the ICU, albeit patients were probably selected hence considered eligible for ICU admission [Citation13]. Organ failure support requirement (invasive mechanical ventilation) and performance status impairment predicted ICU mortality. Those determinants of ICU prognosis underline the need of a close collaboration between oncologists and intensivists when discussing an ICU admission. Performance status is an operational and reproducible factor easily available at the bedside before ICU referral and should be paramount to the decision-making process [Citation5]. Recent guidelines mentioned that cancer patients with poor functional status (performance status 3–4) generally do not benefit from ICU admission [Citation17]. Interestingly, specific oncological complications were not associated with in-ICU mortality, probably because rapidly reversible (hypercalcemia, pleural effusion). This is in sharp contrast to other conditions such as lung cancer, where specific respiratory complications are poorly amenable to efficient chemotherapy or instrumental interventions [Citation18]. Those differences argue for refining our global view of cancer in the ICU toward relevant subgroups of patients with more consistent underlying neoplasms.

The one-year survival rate was poor (42.9%), related to specific complications, impaired performance status (likely to jeopardize the maintenance of optimal antitumoral treatment), and triple-negative breast cancer, usually associated with a worse prognosis [Citation19,Citation20]. Of note, the one-year prognosis was not influenced by the stage of the disease. The description of oncological treatment after ICU discharge is a hallmark of this study. Beyond crude short-term mortality, it is of paramount importance to address the possibilities of maintenance of cancer care following the acute complication [Citation7,Citation21,Citation22]. Despite experiencing life-threatening complications leading to organ failures, antitumoral treatment could be continued or initiated in most hospital-survivors, standing the ICU admission as a bridge to tumor control.

Our study has several limitations. This was a single-center study and the results may not be fully transposable elsewhere. Indeed some patients with moderate severity may be managed outside the ICU in separate high-dependency units in other centers. We did not analyze ICU-admitted patients following surgery because they exhibit different characteristics and prognosis [Citation4]. Despite its retrospective design, we were able to collect accurate features like performance status, a relevant prognostic factor which had not been studied in this setting. Besides crude mortality and the ability to continue antitumoral treatment, we could not appreciate the quality of life, which seems crucial in this population [Citation23].

Conclusion

Life-threatening complications in breast cancer patients are often due to specific complications linked to the underlying malignancy. Four out of 5 patients survived the ICU stay and the short-term prognosis did not depend on oncologic characteristics, therefore supporting a broad ICU admission policy. Although most patients were able to continue the antitumoral treatment after hospital discharge, the one-year mortality rate reached 57.1%. Performance status prior to the acute complication is a relevant prognostic factor for both short-term and long-term outcomes.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. It was approved by the ethics committee from the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française (CE SRLF 17-03) which waived the need for signed consent according to French regulations.

Consent form

This study was approved by the ethics committee from the Société de Réanimation de Langue Française (CE SRLF 17-03) which waived the need for signed consent according to French regulations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. FP: Alexion Pharma (institutional grant), Gilead sciences (consulting and teaching personal fees). JA: Astra Zeneca, MSD, Janssen, GSK, Novartis, Clovis, Eisaï.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33.

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249.

- Carioli G, Malvezzi M, Rodriguez T, et al. Trends and predictions to 2020 in breast cancer mortality in Europe. Breast. 2017;36:89–95.

- Puxty K, McLoone P, Quasim T, et al. Risk of critical illness among patients with solid cancers: a population-based observational study. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(8):1078–1085.

- Zampieri FG, Romano TG, Salluh JIF, et al. Trends in clinical profiles, organ support use and outcomes of patients with cancer requiring unplanned ICU admission: a multicenter cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(2):170–179.

- Caruso P, Ferreira AC, Laurienzo CE, et al. Short- and long-term survival of patients with metastatic solid cancer admitted to the intensive care unit: prognostic factors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(2):260–266.

- Borcoman E, Dupont A, Mariotte E, et al. One-year survival in patients with solid tumours discharged alive from the intensive care unit after unplanned admission: a retrospective study. J Crit Care. 2020;57:36–41.

- Bos MMEM, Verburg IWM, Dumaij I, et al. Intensive care admission of cancer patients: a comparative analysis. Cancer Med. 2015;4(7):966–976.

- Harbeck N, Gnant M. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1134–1150.

- Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710.

- Vigneron C, Charpentier J, Valade S, et al. Patterns of ICU admissions and outcomes in patients with solid malignancies over the revolution of cancer treatment. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):182.

- Destrebecq V, Lieveke A, Berghmans T, et al. Are intensive cares worthwhile for breast cancer patients: the experience of an oncological ICU. Front Med. 2016;3:50.

- Vincent F, Soares M, Mokart D, et al. In-hospital and day-120 survival of critically ill solid cancer patients after discharge of the intensive care units: results of a retrospective multicenter study—A Groupe de recherche respiratoire en réanimation en Onco–Hématologie (Grrr-OH) study. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):40.

- Ostermann M, Raimundo M, Williams A, et al. Retrospective analysis of outcome of women with breast or gynaecological cancer in the intensive care unit. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4(1):2.

- Nassar AP, Dettino ALA, Amendola CP, et al. Oncologists’ and intensivists’ attitudes toward the care of critically ill patients with cancer. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(10):811–817.

- Azoulay E, Soares M, Darmon M, et al. Intensive care of the cancer patient: recent achievements and remaining challenges. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1(1):5.

- Meert A-P, Wittnebel S, Holbrechts S, et al. Critically ill cancer patient’s resuscitation: a Belgian/French societies’ consensus conference. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(10):1063–1077.

- Soares M, Toffart A-C, Timsit J-F, et al. Intensive care in patients with lung cancer: a multinational study. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(9):1829–1835.

- Li X, Yang J, Peng L, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer has worse overall survival and cause-specific survival than non-triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161(2):279–287.

- Agarwal G, Nanda G, Lal P, et al. Outcomes of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) compared with non-TNBC: does the survival vary for all stages? World J Surg. 2016;40(6):1362–1372.

- Schellongowski P, Sperr WR, Wohlfarth P, et al. Critically ill patients with cancer: chances and limitations of intensive care medicine-a narrative review. ESMO Open. 2016;1(5):e000018.

- Vigneron C, Charpentier J, Wislez M, et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with lung cancer and life-threatening complications. Chest. 2021;160(4):1560–1564.

- Normilio-Silva K, de Figueiredo AC, Pedroso-de-Lima AC, et al. Long-term survival, quality of life, and quality-adjusted survival in critically ill patients with cancer. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1327–1337.