Abstract

Background

Oncologist-led follow-up after breast cancer (BC) is increasingly replaced with less intensive follow-up based on higher self-management, which may overburden the less resourceful patients. We examined whether socioeconomic factors measured recently after the implementation of a new follow-up program for BC patients were associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and self-management 12 months later.

Methodology

Between January and August 2017, we invited 1773 patients in Region Zealand, Denmark, to participate in baseline and 12 months follow-up questionnaires. The patients had surgery for low- and intermediate risk BC 1–10 years prior to the survey, and they had recently been allocated to the new follow-up program of either patient-initiated follow-up, or in-person or telephone follow-up with a nurse, based on patients’ preferences. We examined associations between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) at baseline and two outcomes: HRQoL (EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-BR23) and self-management factors (health care provider, confidence in follow-up, contact at symptoms of concern, and self-efficacy) at 12 months follow-up. Sensitivity analyses were performed according to time since diagnosis (≤ 5 > 5 years). Furthermore, we investigated whether treatment and self-management factors modified the associations.

Results

A total of 987 patients were included in the analyses. We found no statistically significant associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL, except in patients ≤ 5 years from diagnosis. For self-management patients with short education were more likely to report that they had not experience relevant symptoms of concern compared to those with medium/long education (OR 1.75 95% CI: 1.04; 2.95). We found no clear patterns indicating that treatment or self-management factors modified the associations between socioeconomics’ and HRQoL.

Conclusion

Overall socioeconomic factors did not influence HRQoL and self-management factors except for experiencing and reporting relevant symptoms of concern. Socioeconomic factors may, however, influence HRQoL in patients within five years of diagnosis.

Background

Breast cancer (BC) and its treatment may have long-term effects on physical and emotional functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [Citation1–3] which may be especially pronounced in women who have comorbidities, shorter educations and low social support [Citation2,Citation4–7]. Traditional follow-up programs after treatment for BC have consisted of routine visits with an oncologist and mainly focused on detection of recurrence, adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy and symptom management [Citation8–10]. However, the efficiency of these programs on detection of recurrence and survival, as well as provision of physical and psychological support have been questioned [Citation11,Citation12]. In order to provide a more efficient BC follow-up, a triaged follow-up approach differentiating follow-up care according to individual recurrence risk and need for support has been suggested [Citation10]. Accordingly, patients with low and intermediate risk of recurrence may e.g., be offered patient-initiated follow-up, whereas high risk patients may be offered routine face-to-face or telephone contacts with either a physician or a nurse [Citation13]. Patient-initiated follow-up emphasizes a strong focus on self-management, as patients are actively involved in managing their health, including recognizing symptoms of recurrence, and understanding when and how to seek support [Citation14,Citation15]. Skills to seek, read and understand health information, social support, and self-efficacy (confidence in the ability to successfully manage difficult situations), may also be important [Citation14,Citation15]. It has been shown that low socioeconomic position (SEP) measured by educational level, income and cohabitation status may lead to less referral to and use of cancer rehabilitation [Citation16,Citation17], and even to shorter survival after treatment for BC [Citation18]. Education is a strong predictor for SEP as it shapes the future occupational position and income, and may also reflect economic and psychosocial resources for a healthy life style and cognitive skills to understand and communicate health information, which may enable use of health services [Citation19,Citation20]. Cohabitation is a strong indicator for social support, which has been shown to improve and maintain HRQoL in BC survivors [Citation4,Citation5] and which may positively influence the use of cancer follow-up programs [Citation15]. Still, the role of education and cohabitation in HRQoL and self-management during BC follow-up has to our knowledge not yet been examined.

In this study, we examine whether the socioeconomic factors education and cohabitation measured recently after the implementation of a new follow-up program are associated with HRQoL and self-management 12 months later. Additionally, we examine if factors related to BC treatment and self-management may modify the associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL. We hypothesize that patients with short education and patients living alone may represent particularly vulnerable groups of patients, with lower HRQoL 12 months later compared to patients with medium/long education and those cohabiting.

Method and material

Follow-up care after treatment for BC

In Denmark, follow-up care after BC has consisted of routine biannual visits with an oncologist for the first five years after surgery followed by annual visits for the subsequent five years. In 2017, the Danish Region Zealand implemented a new BC follow-up program specifically for patients with low or intermediate risk of recurrence (> 40 years of age at diagnosis, stage I-II, without a BRCA gene mutation, and not having had recurrent BC). Patients one to five years after BC surgery could choose between patient-initiated follow-up where patients could contact the department of oncology at symptoms of concern or in-person or telephone contact with a nurse in the outpatient clinic every 6 or 12 months. Patients more than five years after surgery were solely offered patient-initiated follow-up. Although patients were allocated to these fixed programs they were referred to a physician if their symptoms required it. For this study we used the STROBE cohort reporting guidelines [Citation21].

Study population

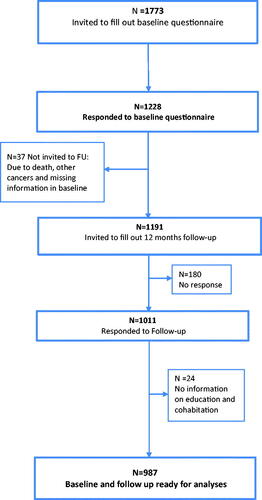

Between January and August 2017, we invited all patients who had recently been enrolled to the new follow-up program in Region Zealand (N = 1773). Participants were asked to provide baseline and 12 months follow-up questionnaires () in order to examine their symptom burden over time. Data from the cohort has in previous studies been used to validate a patient‑reported outcome measure for detecting symptoms of recurrence after breast cancer [Citation22] and the association between education and fear of recurrence [Citation23].

Socioeconomic factors

In the baseline questionnaire, we obtained information on age, length of education and cohabitation. Age was included as a linear variable. Education was categorized as short (basic school 7–10 years), medium (high school and vocational training) or long (college and university). Cohabitation status was categorized as either living with a partner or living alone. Time since diagnosis was categorized as ≤5 and >5 years since surgery.

Patient reported outcomes

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ C-30 and the specific module for BC specific HRQoL QLQ-BR23. The core module QLQ C-30 consists of 30 items which aggregate into one global health status, five functional scales (to assess physical function, role function, emotional function, cognitive function, social function) and nine scales concerning symptoms (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea) and financial difficulties [Citation24]. The 23-item BC specific module EORTC QLQ-BR23 yields scores for four functional scales (body image, sexual functioning, sexual enjoyment and future perspectives) and four symptom scales (arm symptoms, breast symptoms, side effects of systemic therapy and hair loss) which were used to assess arm and breast symptoms, and side effects of systemic therapy [Citation25]. All scores are linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale. Higher scores for functioning indicate better functioning, whereas higher scores for symptoms indicate worse symptoms. Clinical important difference on the EORTC QLQ C-30 has been defined as ‘little change’ 5–10 points; ‘moderate change’ 10–20 points; and ‘very much change’ >20 points [Citation26].

Self-management was measured using four study specific items including type of follow-up care provider that the patient had seen (nurse/physician, secretary/no contact), feeling confident with the follow-up care (yes, no, not relevant) and whether patients contacted the health care system at symptoms of concern (yes, no, no relevant symptoms) and perceived self-efficacy. Self-efficacy was measured with the General Self-efficacy Scale [Citation27] containing 10 items, which assess optimistic self-beliefs to cope with a variety of difficult demands in life. The scale refers explicitly to personal agency, i.e., the belief that one’s actions are responsible for successful outcomes. Perceived self-efficacy may be related to successful coping, which is related to subsequent behavior and therefore relevant for clinical practice and behavior change. All responses add to a sum score. The ranging is from 10 to 40 points [Citation27]. The median score for self-efficacy in the current population was 30 points and patients were categorized according to above and below the median.

Clinical characteristics

Information on clinical characteristics (type of surgery and adjuvant treatments) was elicited from The Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG) [Citation28], which holds detailed information on approximately 95% of Danish breast cancer patients < 75 years of age.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to examine socioeconomic and clinical characteristics by length of education and cohabitation status at baseline. Linear regression models with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to examine associations between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) at baseline and HRQoL domains at 12 months follow-up adjusted for age, HRQoL scores at baseline and time since diagnosis. In order to examine potential impact of missing HRQoL data, multiple imputations were conducted using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (mice). Logistic regression models with 95% CIs adjusted for age and time since diagnosis were used to examine associations between socioeconomic factors at baseline and the four self-management factors at 12 months follow-up: type of follow-up care provider seen, confidence with the follow-up program, contact to the health care system at symptoms of concern and self-efficacy. Sensitivity analyses in sub-groups of patients were performed according to time since diagnosis (≤ 5 > 5 years) in order to examine whether time since diagnosis influenced the associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL and self-management, respectively.

To investigate whether the association between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL differed according to BC treatment (surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy and endocrine therapy), and for self-management factors (follow-up care provider, confidence with follow-up, contact with health care system at symptoms of concern, and self-efficacy), we added these variables one at a time as interaction terms when examining the association between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL. p Values <.05 was considered statistical significant and the statistical software R version 4.0.1 were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Among 1773 invited patients, 1228 (69%) answered the baseline questionnaire and 1011(57%) also returned the 12 months follow-up questionnaire (). The majority of patients (60%) were beyond five years from breast surgery and most patients had patient-initiated follow-up (secretary/no contact) (68%) (). Patients with short education and those living alone were significantly less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, fewer were confident with follow-up and were less likely to contact at symptoms of concern, and more had low self-efficacy ().

Table 1. Baseline sociodemographic and clinical factors, and factors related to treatment and follow-up by length of education and cohabitation status (N = 987).

Socioeconomic factors, HRQoL and self-management factors

We found no statistically significant associations between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) and HRQoL in the overall analyses (). Similar results were seen using multiple imputation methods (data not shown). Among patients ≤ 5 years from diagnosis, patients with short education had significantly higher breast symptoms and patients living alone had poorer social and cognitive function ().

Table 2. Associations between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) and health related quality of life at 12 months follow-up.

Table 3. Associations between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) and health related quality of life at 12 months follow-up among patients ≤ 5 years from diagnosis (N = 401).

For the associations between socioeconomic factors and self-management we found that patients with short education were more likely to report that they had not experienced relevant symptoms of concern between contacts compared to those with medium/long education (OR 1.75 95% CI: 1.04; 2.95) (). Similar results were seen for the sensitivity analyses in patients ≤5 years from diagnosis.

Table 4. Odds ratios of the association between socioeconomic factors (education and cohabitation) and self-management.

Socioeconomic factors and HRQoL stratified by treatment and self-management factors

We found no clear patterns indicating that treatment or self-management factors modified the associations between socioeconomics’ and HRQoL. However, in a few HRQoL domains we did find statistically significant differences according to treatment (chemotherapy) and self-management factors (confidence with follow-up, contact at symptoms of concern and self-efficacy) (Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2).

Discussion

In this large cohort of almost a thousand patients in follow-up after BC, we found no significant associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL and self-management respectively, except for those with short education, who were more likely to report that they had not experienced relevant symptoms of concern between contacts. However, among patients ≤ 5 years from diagnosis, patients with short education did experience higher breast symptoms and patients living alone did have poorer social and cognitive function thus indicating small to moderate clinical differences.

Although our sub-analyses indicated that chemotherapy and selected self-management factors moderated a few associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL in subgroups of patients, no clear patterns were seen, and the signals could be random findings.

We had expected that both education and cohabitation status would be more strongly associated with HRQoL and self-management among patients in BC follow-up care. Previous studies investigating the associations between education, social support and HRQoL in BC patients [Citation4,Citation6,Citation7], have shown that in particular, having a partner is an important predictor for regaining HRQoL following BC treatment [Citation4], as well as an increased use of follow-up care [Citation15]. Other studies on cancer rehabilitation have shown that low socioeconomic position among cancer survivors is associated with less participation in rehabilitation services and higher unmet needs [Citation16,Citation17] perhaps especially for female survivors [Citation16].

The majority (60%) of patients in this cohort were more than five years from diagnosis and overall they reported good global health and similar to that of the general population [Citation29]. The small variance in HRQoL and the fact that most of the patients scored in the upper level of the HRQoL scale may have prevented us in detecting the expected associations between socioeconomic factors and HRQoL in the overall analyses. Our results indicate that socioeconomic factors may influence some domains of HRQoL, but mainly in patients within five years of diagnosis. This aligns with previous studies on BC survivors reporting that the adverse effect of diagnosis and treatment may for most patients attenuate over time and that BC survivors 5–10 years after diagnosis have HRQoL scores comparable to cancer free women [Citation1,Citation2].

We did find that patients with short education were more likely to report that they had not experienced relevant symptoms of concern between contacts, compared to those with medium/long education. This is in line with studies suggesting that health literacy and self-efficacy, often are associated with higher education, which may influence the ability to recognize and report on symptoms [Citation14,Citation15].

Treatment and self-management factors

It is well documented that treatment with chemotherapy, radiation therapy and endocrine therapy influence HRQoL and we would have expected that patients with short education and those who lived alone would be more susceptible for decrements in HRQoL if they had received these treatments [Citation6]. However, we only found that treatment with chemotherapy significantly modified the association between cohabitation and HRQoL. We cannot exclude that the lack of effect modification may be due to the fact that most of the patients in this cohort were years past cessation of adjuvant treatments where symptoms usually have attenuated.

We did find that some self-management factors including confidence with follow-up, contact at symptoms of concern and self-efficacy, significantly modified the association between socioeconomics’ and HRQoL in a few domains. This may be due to chance findings, however, our results may reflect that most patients in this cohort had previously attended routine specialist-led follow-up for more than five years and thus already learnt, how to self-manage symptoms in order to maintain HRQoL.

Our study found that socioeconomic factors measured recently after the implementation of a new follow-up program were largely not associated with HRQoL and self-management 12 months later. This is in accordance with a recent Cochrane review on different cancer follow-up types, which documented that non-specialist versus specialist-led follow up may make little or no difference to HRQoL at 12 months [Citation11] indicating the relevance and safety of less intensive follow-up programs.

Strength and limitations

We had the unique opportunity to systematically follow a large cohort of patients, who were allocated to a new follow-up program after treatment for BC. The strengths of the study include a longitudinal design that allowed us to collect repeated measures on the outcomes. We used validated scales to measure general and BC specific HRQoL and self-efficacy [Citation27]. Finally, we elicited detailed information on treatment from the comprehensive DBCG database [Citation28].

A limitation to this study was the inclusion of a heterogeneous patient population one to 10 years after surgery with the majority being more than 5 years of surgery, where the effect of BC treatment on HRQoL may have attenuated. Although we did find some statistically significant decrements in HRQoL, the clinical importance of these were small to moderate and need further confirmation in future studies. Due to the lack of a control group of patients who did not change their follow-up care we were not able to explore changes in HRQoL according to the former versus the new follow-up program. As no validated scales exist on factors related to self-management, we developed study specific single items and as these were not validated, we cannot exclude measurement bias. As 69% returned baseline and 57% returned both questionnaires, we cannot exclude limitations regarding generalizability. However, in a previous study on this cohort, differences between participants and non-participants were examined and they did not differ according to age, time since diagnosis and treatment factors, except that participants were significantly more likely to have received adjuvant radiotherapy compared to non-participants [Citation22].

Conclusion

Socioeconomic factors were not strongly associated with HRQoL and self-management, except for patients with short education who were less likely to report having experienced relevant symptoms of concern between contacts. However, we did find that in patients closer to diagnosis (≤5 years), some HRQoL domains were affected in patients with shorter education and those living alone. Thus, further attention may be needed to ensure that socially vulnerable are supported during follow-up after cancer.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required, as no biological samples were obtained from participants. The study was registered locally in the Danish Cancer Society Research Database (2018-DCRC-0011) and all data are treated confidentially and stored according to EU General Data Protection Regulation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [RK], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hsu T, Ennis M, Hood N, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3540–3548.

- Karlsen RV, Frederiksen K, Larsen MB, et al. The impact of a breast cancer diagnosis on health-related quality of life. A prospective comparison among middle-aged to elderly women with and without breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(6):720–727.

- Trentham-Dietz A, Sprague BL, Klein R, et al. Health-related quality of life before and after a breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109(2):379–387.

- Leung J, Smith MD, McLaughlin D. Inequalities in long term health-related quality of life between partnered and not partnered breast cancer survivors through the mediation effect of social support. Psychooncology. 2016;25(10):1222–1228.

- Leung J, Pachana NA, McLaughlin D. Social support and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2014;23(9):1014–1020.

- Høyer M, Johansson B, Nordin K, et al. Health-related quality of life among women with breast cancer - a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(7):1015–1026.

- Graells-Sans A, Serral G, Puigpinós-Riera R. Social inequalities in quality of life in a cohort of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Barcelona (DAMA Cohort). Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;54:38–47.

- Moschetti I, Cinquini M, Lambertini M, et al. Follow-up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(5):CD001768.

- Taggart F, Donnelly P, Dunn J. Options for early breast cancer follow-up in primary and secondary care - a systematic review. BMCCancer. 2012;12:238.

- Watson EK, Rose PW, Neal RD, et al. Personalised cancer follow-up: risk stratification, needs assessment or both? Br J Cancer. 2012;106(1):1–5.

- Høeg BL, Bidstrup PE, Karlsen RV, et al. Follow‐up strategies following completion of primary cancer treatment in adult cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(11):CD012425.

- Fiszer C, Dolbeault S, Sultan S, et al. Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2014;23(4):361–374.

- Rose PW, Watson E. What is the value of routine follow-up after diagnosis and treatment of cancer? Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(564):482–483.

- Foster C, Breckons M, Cotterell P, et al. Cancer survivors’ self-efficacy to self-manage in the year following primary treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(1):11–19.

- Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Kent EE, et al. Social support, self-efficacy for decision-making, and follow-up care use in long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2014;23(7):788–796.

- Holm LV, Hansen DG, Larsen PV, et al. Social inequality in cancer rehabilitation: a population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):410–422.

- Moustsen IR, Larsen SB, Vibe-Petersen J, et al. Social position and referral to rehabilitation among cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(5):720–726.

- Carlsen K, Høybye MT, Dalton SO, et al. Social inequality and incidence of and survival from breast cancer in a population-based study in Denmark, 1994-2003. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(14):1996–2002.

- Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, et al. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

- Khalatbari-Soltani S, Maccora J, Blyth FM, et al. Measuring education in the context of health inequalities. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51(3):701–708.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger MP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349.

- Høeg BL, Saltbæk L, Christensen KB, et al. The development and initial validation of the Breast Cancer Recurrence instrument (BreastCaRe)-a patient-reported outcome measure for detecting symptoms of recurrence after breast cancer. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(9):2671–2682.

- Larsen C, Kirchhoff KS, Saltbæk L, et al. The association between education and fear of recurrence among breast ccancer patients in follow-up - and the mediating effect of self-efficaccy. Acta Oncol. 2023. DOI:10.1080/0284186X.2023.2197122

- Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365–376.

- Sprangers MA, Groenvold M, Arraras JI, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer breast cancer-specific quality-of-life questionnaire module: first results from a three-country field study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(10):2756–2768.

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144.

- Luszczynska A, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. The general self-efficacy scale: multicultural validation studies. J Psychol. 2005;139(5):439–457.

- Moller S, Jensen MB, Ejlertsen B, et al. The clinical database and the treatment guidelines of the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group (DBCG); its 30-years experience and future promise. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(4):506–524.

- Juul T, Petersen MA, Holzner B, et al. Danish population-based reference data for the EORTC QLQ-C30: associations with gender, age and morbidity. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(8):2183–2193.