Abstract

Background

The Danish head and neck cancer fast-track program is a national standardized pathway aiming to reduce waiting time and improve survival for patients suspected of cancer in the head and neck (HNC). Until now, the frequency of missed cancer in the fast-track program has not been addressed. A missed cancer leads to treatment delay and may cause disease progression and worsening of prognosis. The study objective was to estimate the frequency of patients with missed cancers in the Danish HNC fast-track program and to evaluate the accuracy of the program.

Materials and Methods

Patients who were rejected from the HNC fast-track program because cancer was not found between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2018 at Odense University Hospital, Denmark were included and followed for three years. Patients were categorized into groups depending on the diagnostic evaluation. Group 1 included patients evaluated with standard clinical work-up without imaging and biopsy. Group 2 included patients evaluated with imaging and/or biopsy in addition to the standard clinical work-up. The local cancer database and electronic patient records were reviewed to determine if a missed cancer had occurred within the follow-up period.

Results

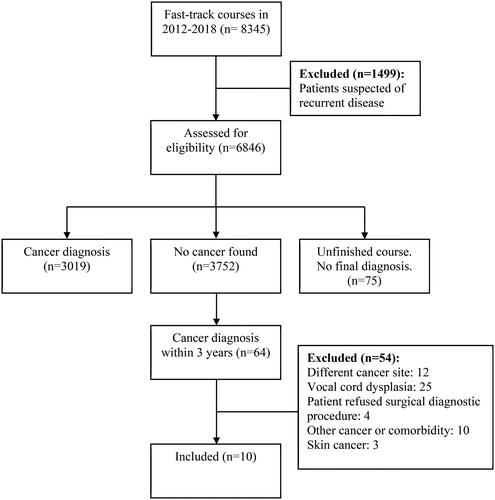

A total of 8345 HNC fast-track courses were initiated during the study period. 1499 were patients suspected of recurrent cancer and were excluded leaving 6846 patients to be assessed for eligibility. Of these, 3752 patients were rejected because cancer was not found. Ten patients were subsequently diagnosed with cancer within the follow-up period resulting in an overall frequency of 0.15%. For group 1 and 2, the frequency was 0.04% and 0.10%, respectively. The sensitivity of the fast-track program was 99.67% and the negative predictive value was 99.73%.

Conclusion

The frequency of missed cancer in a tertiary HNC center following the Danish fast track program is low.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a heterogeneous group of malignant tumors invading essential anatomical and functional sites. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the predominant tumor type and accounts for more than 90% of HNC [Citation1]. In Denmark, approximately 50% of patients with HNC present with SCC in an advanced stage (III-IV) [Citation2]. Several studies have confirmed the association between prolonged time to treatment and decreased survival rates [Citation3–5]. It is important to prioritize early recognition of symptoms, fast diagnosis, and timely treatment to improve the prognosis.

In Denmark, almost all tumor types are diagnosed and treated in fast-track programs. The fast-track programs were introduced by the Danish Health Authority in 2007 as standardized pathways including a systematic use of pre-booked slots in the diagnostic hospital units. The programs were developed to ensure that all Danish citizens have equal access to a fast and efficient diagnostic process and the highest quality of treatment.

The program for HNC has been running nationally since 2008 and was the first of its kind in the world [Citation6,Citation7]. At Odense University Hospital more than 90% of the patients complete their diagnostic course within the permitted time frames [Citation6]. The implementation of the program has resulted in a significant reduction in the median time from referral to final diagnosis from 24 days to 10 days as shown by Sørensen et al. [Citation7].

Referrals for the HNC fast-track are typically made by private ear-nose-throat (ENT) specialists or other hospital departments. In Denmark, there is a substantial amount of private ENT specialists (32/1 million inhabitants), and they serve as a filter for the fast-track program [Citation6]. If a physician in primary care suspects cancer in the head and neck region the patient must be seen by a private ENT specialist within two days. If the suspicion of cancer is well justified, the patient will then be referred to the nearest ENT hospital department. Patients referred to the fast-track program must be seen in the ENT department within six calendar days from referral. On the first day, the patient will be examined by an ENT doctor. The appointment consists of a standard work-up including medical history, basic clinical ENT exam, endoscopic naso-pharyngo-laryngoscopy, and clinical ultrasound of the neck as well as relevant fine-needle aspirations (FNA).

For some patients, the suspicion of HNC is disproved after the first visit, and the fast-track course is terminated. If treatment for a benign condition is needed, the patient will be transferred to conventional diagnostics and treatment, otherwise, their course will be terminated with no further planning. The patient will continue in the fast-track course with additional examinations if there is a well-founded suspicion of cancer. Diagnostic imaging (PET-CT/MRI/CT) and relevant tumor biopsies are performed in the following days. If these examinations disprove the suspicion of cancer the fast-track course is terminated [Citation6,Citation8].

At Odense University Hospital, approximately 1300 patients are referred to the fast-track with suspected cancer in the head and neck area each year. The overall malignancy detection rate has been determined to be 40.6% of which 29.2% are HNC, 5.3% are lymphomas and 6.1% are other cancers presenting in the head and neck region. Consequently, 59.4% of the referred patients are rejected from the fast-track because cancer is not found. [Citation6]. Until now, the frequency of missed cancer diagnoses, i.e., false negative diagnoses in this group of patients, has not been addressed. False negative diagnoses may result in treatment delay associated with disease progression and decreased survival rates [Citation3–5]. The objective of this study was to estimate the frequency of patients with missed cancer in the Danish HNC fast-track program and to evaluate the accuracy of the program.

Materials and method

This study was a register-based descriptive cohort study. All patients rejected from the HNC fast-track program because cancer was not found between 1 July 2012 and 31 December 2018 at Odense University Hospital were included. Patients where a recurrence was suspected, patients who died before establishment of diagnosis, and patients refusing to follow the fast-track program were excluded.

The included patients were divided into groups depending on the diagnostic evaluation. Group 1 included the patients evaluated with standard clinical work-up including ENT exam and ultrasound of the neck at the first appointment. Group 2 included the patients who had diagnostic imaging performed and/or biopsies taken in addition to the standard workup.

Each patient was followed up to 3 years. Follow-up time began on the date of the first visit to the fast-track course. Patients returning to the fast-track program and diagnosed with a malignant tumor in the head and neck region within 3 years from the initial fast-track evaluation were classified as false negatives. The following criteria had to be fulfilled: the localization of the subsequent cancer had to be in the same site as the initial suspicious site. Patients put under observation (e.g., vocal cord dysplasia) who later developed cancer were excluded. All cancers presenting in the head and neck except skin cancer were investigated. Skin cancer does not have its own fast-track program. Patients suspected of skin cancer in the head and neck area are sometimes examined in the HNC fast track for practical reasons. However, they are not systematically referred, nor do they represent the usual HNC population, and were therefore excluded from this study.

Patients eligible for the study were identified from the local quality database for HNC. All patients going through an HNC fast-track course at Odense University Hospital are consecutively registered. Throughout the past ten years, data have been collected for more than 13,000 patients. The database holds information on patient demographics, diagnostic methods, International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis, and treatment modalities. Additional data needed for this study were obtained from medical records.

Descriptive statistics were used. Fisher’s Exact Test was used to test for an association between groups 1 and 2. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Additionally, the sensitivity and the negative predictive value of the fast-track program as a diagnostic test for HNC were determined. The statistical software Stata 17 (StataCorp 2021, College Station, TX) was used for analyses.

The study was a quality assurance project. Approval was obtained from the hospital board at Odense University Hospital. Ethics Committee approval is not required for quality projects according to Danish law. Permission to handle data was obtained from the Region of Southern Denmark (21/18712).

Results

Between 2012 and 2018 a total of 8345 fast-track courses were initiated at Odense University Hospital. Of these 1499 (18.0%) patients were suspected of recurrent disease and were excluded. Consequently, 6846 (82.0%) patients were assessed for eligibility (). Out of 6846 patients, 3019 (44.1%) were diagnosed with cancer, 3752 (54.8%) were rejected because cancer was not found, and 75 (1.1%) did not receive a final diagnosis.

Sixty-four of the 3752 patients returned to the fast-track course with a malignant tumor within three years. Twelve of 64 were excluded because the cancer was in another site unrelated to the one suspected in the initial course. For example, a patient suspected of thyroid cancer but diagnosed with nontoxic multinodular goiter returned to the fast track two years later with tongue cancer. Twenty-five of 64 patients had vocal cord dysplasia and were excluded. They were observed and treated for precancerous lesions at regular intervals in an ordinary ENT setting outside the fast-track. When suspicion of progression to SCC occurred, they were referred to the fast track again. Four of 64 patients were excluded because they refused a surgical diagnostic procedure. They later changed their mind and were reenrolled in the fast-track and diagnosed with cancer. Ten of 64 patients were suspected or treated for cancer outside the head and neck region and/or had substantial comorbidity that required treatment before a diagnosis of HNC was possible. In these cases, the initial fast-track course was intentionally terminated and resumed when the patient was able to undergo diagnostics. Finally, three of the 64 patients had skin cancer. There were ultimately ten courses that fulfilled the criteria for being a false negative diagnosis (). There were six men and four women between the age of 48 and 88 years (median 64). The interval between the first and second fast track courses varied from 42 days to 1027 days with a median of 464 days. Four patients were diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer, two with lymphoma in the head and neck region, two with thyroid cancers, one with salivary gland cancer, and one with laryngeal cancer ().

Table 1. Comparison of the first and second fast-track course for the ten cases of missed cancer.

Table 2. Characteristics of the patients with missed cancer.

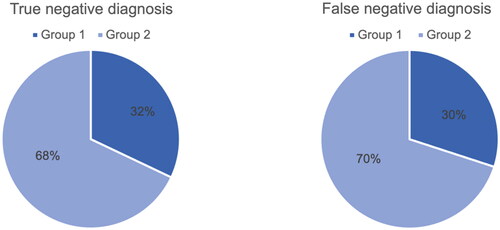

All included patients were divided into diagnostic groups (). For the true negatives 1199 (32.04%) belonged to group 1 and 2543 (67.96%) to group 2. For the false negatives three (30.0%) were in group 1 and seven (70.0%) in group 2. Fisher’s exact test did not indicate a significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.595).

Figure 2. Comparison of diagnostic groups for patients rejected from the fast-track program because cancer was not found. Group 1 = no biopsy or imaging. Group 2 = biopsy and/or imaging. Negative diagnosis = no cancer found.

Ten cases of missed cancer out of 6846 fast-track courses resulted in an overall frequency of missed cancer of 0.15%. For group 1 and group 2, the frequency was 0.04% and 0.10%, respectively. Finally, the sensitivity of the fast-track was determined to be 99.67% and the negative predictive value was 99.73%.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the frequency of missed cancer in a standardized cancer pathway set-up for HNC. Around 1400 patients are referred to the fast-track program for HNC at Odense University Hospital every year. More than half of them do not have cancer. The paradox of seeing a considerable number of healthy patients in a cancer pathway was one of the reasons for carrying out this study.

Missed cancer for patients diagnosed in the fast-track program was rare. Defining an acceptable rate for missed cancer is difficult especially when there is no comparable data. First, because the specific issue of missed cancer has not been investigated in a similar setting. Most studies on fast-track programs focus on the reduction of waiting time, malignancy detection rate and referral symptoms. Second, the specific set-up for fast-track diagnostics differs somewhat between countries. Nevertheless, the principle of standardized cancer pathways has become more widespread especially in European countries. The United Kingdom is one of the countries with the longest-running fast-track program, the two-week wait rule implemented in 2000. However, their conversion rates, i.e., the proportion of referred patients diagnosed with cancer are very low compared to Denmark. A systematic review found a pooled conversion rate of 8.8% in the British two-week wait system for HNC [Citation9]. In our study, 44.1% of the referred patients were diagnosed with cancer. Only patients with a suspected primary cancer and not recurrent cancer were assessed in the present study. However, Rønnegaard et al. [Citation6] found a similar malignancy rate of 40.6% when assessing primary and recurrent disease in a similar cohort in 2017. The use of private ENT specialists as gatekeepers for the fast track is an important aspect to consider when comparing conversion rates in Denmark with other countries. In the Danish fast-track program, a specialist has already confirmed the suspicion of cancer for a large proportion of the referred patients before they are referred to hospital ENT departments. Sweden [Citation10] and Norway [Citation11] launched cancer patient pathways in 2015 based on the Danish model although it seems studies focusing exclusively on HNC pathways has not been conducted when reviewing the existing literature. Additionally, the region of Catalonia in Spain has commenced a fast-track program aiming to reduce delays in diagnosis and treatment [Citation12, Citation13].

It could be argued that even one case of missed cancer is one too many considering the potential serious consequences for the patient. Nonetheless, during the study period, 6846 patients were assessed and ultimately the system only failed in 10 cases equivalent to a frequency of less than 0.15%. Correspondingly, the sensitivity was determined to be 99.67% indicating that the fast-track program has a high diagnostic value. The equivalently high negative predictive value of 99.73% can be of great value for the patients because it indicates the probability of not having cancer when the fast-track course is terminated.

It is noteworthy that a third of the rejected fast-track patients were evaluated without diagnostic imaging and tumor biopsy, relying completely on the physician’s clinical experience. Perhaps, it would be expected that if the fast-track program had an alarming number of false negative diagnoses, they would appear in the group of patients evaluated without imaging and biopsy. However, the opposite appeared to be true. First, the overall frequency of false negative diagnoses was remarkably low and second the majority occurred in group 2. Only a small proportion (0.04%) were actual diagnostic failures where the patient was incorrectly diagnosed on their first consultation. Results could suggest that clinical experience plays an important role in achieving the low frequency of missed cancer. It should be considered that diagnostic imaging and tissue sampling is subjected to the risk of false negative diagnoses, especially in small lesions emphasizing the importance of an experienced physician.

In group 2 five out of seven patients had a tumor biopsy taken and diagnostic imaging performed. Six out of seven patients had diagnostic imaging performed and PET/CT was used for all of them either alone or supplemented by MRI and/or chest x-ray. The patients had the available and relevant diagnostic procedures performed however, the cancer was apparently not possible to detect at this point. Patient no. 3 and no. 7 were diagnosed with cancer after 4 months but the remaining five went at least a year before being diagnosed.

Three years were chosen as the maximum observation time. This is arguably a long time, and it can be discussed if it is likely to detect a cancer three years before the actual diagnosis. It is possible that a benign diagnosis would cause a patient to delay consulting a doctor when their symptoms persisted. Patient no. 1, 2 and 4 returned with a cancer 2–3 years after their first course. Patient no. 5, 6, and 10 returned after 1-2 years. Patient no. 3, 7, 8, and 9 returned within the first 4 months. Notably for six out of ten patients it took more than a year before the cancer was diagnosed leading us to believe that three years was an acceptable observation time. Anything shorter would only have resulted in a lower frequency of false negatives diagnoses.

One of the strengths of this study is that the database for HNC includes all patients referred to the fast-track program at Odense University Hospital. The fast-track program is the exclusive path for diagnosis and treatment of cancer in Denmark. This means that if a substantial suspicion of cancer arises in another setting, e.g., another hospital department the patient must be referred to the fast-track program. Furthermore, registration of all fast-track patients even those who are not diagnosed with cancer is prioritized. Thus, the cohort is complete making it possible to generate results highly representative of the true population.

A potential limitation is that this study only included patients diagnosed at Odense University Hospital. The fast-track program is national and implemented by legislation making these results generalizable for other HNC centers in Denmark. However, it cannot be ruled out that there are some local discrepancies between the centers.

It should be noted, that in the Region of Southern Denmark patients are referred to the fast-track program for HNC in four different hospitals depending on their residence. However, if HNC is diagnosed in a non-university hospital the patient will be transferred to Odense University Hospital for the multidisciplinary team conference and the subsequent treatment. The patient is also referred if they need more extensive diagnostic work-up only available in a university hospital. Patients are not registered in the database if the suspicion of cancer is rejected in another hospital. It is possible that the frequency of missed cancer was underestimated in this study because it was not known if cancer patients from non-university hospitals had been misdiagnosed before referral.

There is no doubt that the fast-track set-up demands many resources in a time where allocation of public health care services as well as sustainability is continuously discussed. With this study, it was demonstrated that our approach to diagnosing HNC ensures detection of malignancies to such an extent that the risk of overlooking cancer can practically be eliminated.

Acknowledgements

Data management was provided, and REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) was hosted by OPEN (Open Patient data Explorative Network), Odense University Hospital, Region of Southern Denmark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The local quality database for HNC and access to medical records were used under license and thus are not publicly available. Restrictions apply to the availability due to it containing identifiable patient data. Derived de-identified supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mody MD, Rocco JW, Yom SS, et al. Head and neck cancer. Lancet. 2021;398(10318):2289–2299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01550-6.

- Årsrapport 2021 for den kliniske kvalitetsdatabase DAHANCA [PDF]. 2021. Available from: https://www.dahanca.dk/CA_Adm_Web_Page?WebPageMenu=3&CA_Web_TabNummer=0.

- Jensen AR, Nellemann HM, Overgaard J. Tumor progression in waiting time for radiotherapy in head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84(1):5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.001.

- Murphy CT, Galloway TJ, Handorf EA, et al. Survival impact of increasing time to treatment initiation for patients with head and neck cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(2):169–178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.5906.

- Liao DZ, Schlecht NF, Rosenblatt G, et al. Association of delayed time to treatment initiation with overall survival and recurrence among patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in an underserved urban population. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(11):1001–1009. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2414.

- Roennegaard AB, Rosenberg T, Bjørndal K, et al. The Danish head and neck cancer fast-track program: a tertiary cancer centre experience. Eur J Cancer. 2018;90:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.10.038.

- Sorensen JR, Johansen J, Gano L, et al. A "package solution" fast track program can reduce the diagnostic waiting time in head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271(5):1163–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2584-z.

- Pakkeforløb for hoved- og halskræft [PDF]. 2020. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2020/Hoved-halskraeft/220620-Pakkeforloeb-for-hoved–og-halskraeft.ashx?sc_lang = da&hash = C7872017C6C53931F85B36C8E2F0489F

- Langton S, Siau D, Bankhead C. Two-week rule in head and neck cancer 2000-14: a systematic review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54(2):120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.09.041.

- Wilkens J, Thulesius H, Schmidt I, et al. The 2015 national cancer program in Sweden: introducing standardized care pathways in a decentralized system. Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1378–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.008.

- Melby L, Håland E. When time matters: a qualitative study on hospital staff’s strategies for meeting the target times in cancer patient pathways. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06224-7.

- Prades J, Espinàs JA, Font R, et al. Implementing a cancer fast-track programme between primary and specialised care in Catalonia (Spain): a mixed methods study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(6):753–759. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.308.

- Martínez MT, Montón-Bueno J, Simon S, et al. Ten-year assessment of a cancer fast-track programme to connect primary care with oncology: reducing time from initial symptoms to diagnosis and treatment initiation. ESMO Open. 2021;6(3):100148. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100148.