Abstract

Background

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder (AjD) are common in hematological cancer patients as they face severe stressors during their serious disease and often intensive treatment, such as stem cell transplantation (SCT). Aims of the present study were to provide frequency and risk factors for PTSD and AjD based on updated diagnostic criteria that are lacking to date.

Material and methods

In a cross-sectional study, hematological cancer patients were assessed for stressor-related symptoms via validated self-report questionnaires based on updated criteria for PTSD (PCL-5) and AjD (ADMN-20). Frequency and symptom severity were estimated among the total sample and SCT subgroups (allogeneic, autologous, no SCT). SCT subgroups were compared using Chi-squared-tests and ANOVAs. Linear regression models investigated sociodemographic and medical factors associated with symptomatology.

Results

In total, 291 patients were included (response rate: 58%). 26 (9.3%), 66 (23.7%) and 40 (14.2%) patients met criteria for cancer-related PTSD, subthreshold PTSD and AjD, respectively. Symptom severity and frequency of criteria-based PTSD and AjD did not differ between SCT subgroups (all p > 0.05). Factors associated with elevated symptomatology were younger age (PTSD: p < 0.001; AjD: p = 0.02), physical comorbidity (PTSD: p < 0.001; AjD: p < 0.001) and active disease (PTSD: p = 0.12; AjD: p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Based on new criteria, a considerable part of hematological cancer patients reports PTSD and AjD symptoms. Younger patients and patients with physical symptom burden might be particularly at risk and need to be monitored closely to enable effective treatment at an early stage.

Introduction

Cancer diagnosis and its treatment pose great stressors on patients. Consequently, it may be accompanied by symptoms of posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) or adjustment disorder (AjD) [Citation1–3]. Prevalence rates in cancer patients vary from 2 to 19% [Citation1,Citation3–6] for PTSD and 11 to 39% [Citation1,Citation2,Citation7–9] for AjD, mostly based on breast cancer patients and mixed cancer patients. Stressor-related symptoms may lead to decreased use of follow-up care and worse treatment adherence [Citation10,Citation11]. They may consequently impact medical outcomes and mortality of the underlying cancer disease and should be identified and addressed early on.

Among cancer patients, the subgroup of hematological cancer survivors seems to be particularly exposed to stressors. Even though great advancements have been made in diagnostic, treatment, and survival rates of hematological malignancies [Citation12,Citation13], some patients suffer on chronic hematological malignancies, others have a high cancer relapse rate [Citation14] and show increased risks for second malignancies [Citation15]. A subset is treated with autologous [Citation16] or allogeneic [Citation17] stem cell transplantation (SCT), which poses severe burden on the patients requiring spatial isolation and bearing high risk of life-threatening complications and infections [Citation18]. Furthermore, patients undergoing allogeneic SCT are at risk for developing alloimmune complications, that is, graft-versus-host-disease (GvHD) [Citation19]. These stressors may lead to high levels of distress and uncertainty, which has been shown to increase symptoms of PTSD in this population [Citation20].

High variability in frequencies of PTSD and AjD between studies is often attributed to heterogenic sample characteristics such as diagnoses or disease states, requiring studies on specific patient groups, and assessment methods such as clinical diagnostic interviews or self-report screeners. Although screeners tend to show higher prevalence than interviews [Citation21,Citation22], they are particularly relevant for screening procedures within clinical care. Most previous studies are based on diagnostic criteria applied from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), or the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). The revision of the ICD-11 introduced important changes and PTSD and AjD are now subsumed in the new chapter ‘Disorders Specifically Associated with Stress’. Changes in diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 and ICD-11, specially regarding the definition of disorders and symptoms needed, require a new evaluation of the frequency and severity of symptoms. New self-report screening tools for PTSD and AjD based on updated criteria have been introduced and validated [Citation23,Citation24], but have been sparsely studied in oncological patients [Citation7,Citation25,Citation26]. This would be highly relevant for understanding the frequency and severity of symptoms for appropriate psycho-oncological care planning.

Studies addressing associated factors with elevated PTSD and AjD symptoms in cancer patients identified sociodemographic [Citation27–30], that is, younger age, reduced social support, less education and income, and medical risk factors [Citation27–30], that is, disease status, physical comorbidities and longer hospital stays. However, studies on associated factors in hematological cancer patients and based on updated criteria are still sparse, which would be highly relevant for medical care planning. Additionally, the impact of SCT in general and type of SCT on PTSD and AjD remain unclear. A study among 886 non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients showed treatment with SCT to increase PTSD symptoms, however, not when tested independently from other sociodemographic and medical variables [Citation28].

Given the limitations outlined above, the aims of the present study were as follows: (i) to provide the frequency of cancer-related PTSD and AjD symptomatology according to updated diagnostic criteria in hematological cancer patients, (ii) to investigate differences in PTSD and AjD symptomatology depending on SCT treatment and type of SCT, and (iii) to evaluate associated medical and sociodemographic factors. Findings may help to assess the magnitude of psychosocial burden in hematological cancer survivors and identify patients at risk for PTSD and AjD to provide and improve adequate and effective treatment.

Materials and methods

Participants

In this observational cross-sectional study, patients were consecutively recruited between April 2019 and September 2021 at different wards and the outpatient unit of the Clinic for Hematology, Cellular Therapy and Hemostaseology at University Medical Center Leipzig.

Patients were included if they were (i) diagnosed with any hematological malignancy (ICD-10: C81-C96), myelodysplastic syndrome (D46), or other neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behavior of the lymphoid, hematopoietic and related tissues (D47), (ii) between 18 and 70 years (maximum age was set to prevent age bias between patients with and without SCT), (iii) fluent in German language, (iv) cognitively able to provide informed consent and (v) had no plans of re-admission during study assessment. To enable valid comparison between patients with and without SCT, additional criteria were defined: (i) SCT patients were included if they had gone through SCT within the last two years and (ii) patients without SCT were included if they had never been treated with any SCT. Preexisting mental illness was not included as eligibility criterion in order to obtain a representative and unbiased sample of all hematological cancer patients.

Written informed consent was provided by all participants prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Leipzig (447/17-ek) and has been published [Citation31].

Recruitment

Patients at different wards who were receiving oncological treatment at that time were initially screened for eligibility by treating physicians and then approached by a study member after providing the consent to be contacted. To reduce personal contacts during COVID-19 pandemic and burden on physicians, the recruitment process was adapted during the study. Subsequently, all patients scheduled for the hematological outpatient unit who had received or were receiving oncological treatment at that time were checked for eligibility by a study member via review of the medical chart. Eligible patients were then contacted by mail, E-mail, or phone. All eligible patients were informed about the aims and the protocol of the study and asked for participation. Eligible patients who refused to participate were asked to give their reason for refusal and were considered nonresponders. Patients were included at all stages of the oncological treatment process. Few patients were additionally recruited by other sources, that is, after presenting the study at a patient congress and advertisement within two nationwide blood cancer organizations.

Data collection

Participants received a paper-pencil questionnaire by mail. They were additionally assessed with a structured clinical interview via phone or in person that is not part of the present analysis and will be addressed in another publication. If the questionnaire was missing, participants were reminded up to five times every 2–4 weeks via phone. The number and timing of reminders were adjusted to the patients’ respective clinical status, for example, hospitalization or relapse. The assessment was at a minimum of six weeks after the end of treatment to ensure that acute stressors had ended. If patients received a permanent treatment, they were assessed directly after inclusion. Patients who completed the whole assessment received 20 Euros as incentive.

Outcome assessment

The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist (PCL-5) [Citation23] assesses current PTSD symptoms according to DMS-5 via self-report and is validated in German language [Citation32]. The 20 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘extremely’). Higher values indicate higher symptomatology. The instrument enables calculation of a sum score between 0 and 80 and symptom clusters on intrusion, avoidance, negative cognitions/emotions and hyperarousal. We assessed cancer-related PTSD symptoms by instructing participants to refer only to stressful or traumatic events related to their cancer disease and associated treatment. No PTSD symptoms triggered by other traumatic events were recorded. Detailed assessment of cancer-related traumatic events is part of another publication (Springer at al., in review). The PCL-5 enables DSM-5 criteria-based diagnosis of PTSD and shows excellent reliability (α = 0.95) and validity [Citation23,Citation32]. If the symptoms do not meet full criteria, subthreshold PTSD may be present if two symptom clusters are present [Citation33].

The adjustment disorder new module (ADNM-20) [Citation24], validated in German language [Citation34], assesses AjD symptoms according to ICD-11 with 20 items, whereby one item assesses functional impairment. Symptoms are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (‘never’) to 4 (‘often’) with a sum score between 20 and 80. Higher values indicate higher symptomatology. Items can be grouped into two core symptom clusters, that is, preoccupations and failure to adapt, and four feature clusters, that is, avoidance, depressive mood, anxiety, and impulse disturbance. AjD symptoms were only assessed for stressful events in the course of the cancer disease, analogous to the assessment of cancer-related PTSD. The ADNM-20 enables classification as high risk for AjD. The scale shows good reliability (α = 0.85 – 0.92) and validity [Citation34,Citation35].

Sociodemographic and medical data were extracted from the medical charts (i.e., age, sex, diagnosis, date of diagnosis, relapse, type, and date of SCT) and the questionnaire (i.e., education, employment, partner, remission status, days in hospital/isolation, type and date of other treatment, physical comorbidities).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics on sample characteristics are provided for the total sample. Non-responder-analyses were conducted among all patients screened at the outpatient unit, as reasons for nonparticipation were only fully available for this subset of patients, using Chi-square- and independent t-test.

First, we provide the frequency and severity of PTSD and AjD symptomatology for the total sample. Second, we stratify these by SCT subgroups (allogeneic, autologous, no SCT). Differences between subgroups will be analyzed using Chi-square-tests for frequencies and analyses of variance (ANOVA) for symptom severity. In case of differences between subgroups, possible confounders in sample characteristics will be investigated. Third, we use a multistep approach to investigate associated factors: Univariate linear regression models are performed on the two dependent variables PTSD and AjD sum score, with each sociodemographic (binary: age, sex, partner; categorical: education) and medical factor (binary: remission (active disease/remission), relapse (yes/no), SCT (yes/no); continuous: time since diagnosis, days in hospital, number of physical comorbidities) as independent variable entered into separate models. Then, all relevant factors identified as significant in univariate regression models are entered in multiple linear regression models. Effect sizes for independent variables are reported as Cohen’s f2 with small, medium and large effects at ≥0.02, ≥0.15, and ≥0.35, respectively [Citation36]. Given that some of the medical factors only occur in the context of SCT (type of SCT, days spent in isolation, GvHD) the same procedure is repeated in the subset of patients receiving any SCT.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of 5%. Analyses were performed using R statistics software (version 4.1.0).

Results

Sample characteristics

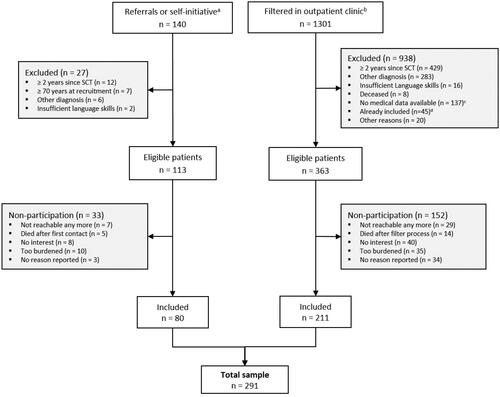

From all 363 eligible patients filtered at the outpatient unit, 211 participated in the study (response rate 58%). Most common reasons for nonparticipation was no interest and being too burdened. Together with patients from initial recruitment procedure from different inpatient wards, 291 patients were included (). Participants were on average 55 years, 174 (60%) were male (). Most common diagnoses were multiple myeloma and myeloid leukemia. Average time since diagnosis was 24 months. 161 (55%) received any SCT.

Figure 1. Flow-diagram. aReferred by physicians at the study center and self-initiated contact of interested patients. bAll patients between 18 and 70 years who were scheduled for the hematological outpatient clinic at the days of recruitment. cNo medical information in the medical records, for example, stem cell donors or patients from other institutions seeking second medical opinion. dAlready recruited by physicians in the first recruitment period (see left recruitment arm).

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

No differences were observed between responders and non-responders in age (p = 0.14), sex (p = 0.14), time since diagnosis (p = 0.74), type of diagnosis (p = 0.12) and SCT treatment (p = 0.94). Patients in SCT subgroups did not differ in sex (p = 0.13) and time since diagnosis (p = 0.26). However, patients without SCT were younger than patients with allogeneic or autologous SCT (p < 0.001). In line with clinical practice guidelines, patients with Multiple Myeloma (p < 0.001) were more likely to receive SCT, whereas patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (p = 0.004), Non-follicular Lymphoma (p = 0.02) and other diagnoses (p < 0.001) were less likely to receive SCT.

285 of 291 patients filled in the questionnaire and were considered for further analyses.

Frequency of cancer-related PTSD and AjD

In total, 26 (9.3%) patients met DSM-5 criteria for cancer-related PTSD (). Another 66 (23.7%) were classified as subthreshold PTSD. The symptom clusters intrusion, avoidance, cognition/mood, and hyperarousal were met in 94 (33.7%), 65 (23.3%), 73 (26.2%), and 78 (28.0%) patients, respectively.

Table 2. Frequencies, symptom clusters, and symptom severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder (AjD) among the total sample and different stem cell transplantation (SCT) subgroups.

In addition, 40 (14.2%) patients screened positive for cancer-related AjD according to ICD-11, and 65 (23.1%) reported high values (≥3) in functional impairment. Core symptom clusters preoccupations and failure to adapt were met by 120 (42.6%) and 115 (40.1%), respectively. Further, 159 (56.4%) patients met at least one core symptom cluster.

Differences in PTSD and AjD symptomatology depending on SCT treatment

Patients in SCT subgroups did not differ in frequencies of symptom clusters, full nor subthreshold PTSD, as well as overall and cluster symptom severity (). No differences were observed in frequencies of AjD diagnosis and symptom clusters, as well as overall and cluster symptom severity.

Associated medical and sociodemographic factors

Following significant sociodemographic and medical variables from univariate regression models were analyzed with multiple regression models: sex, remission status, age and number of physical comorbidities. Analysis revealed that being younger and having more physical comorbidities were associated with increased PTSD symptoms, with small and medium effect sizes respectively (). Additionally, being younger, having an active disease and more physical comorbidities were associated with increased AjD symptoms, with small, small, and medium effect sizes respectively.

Table 3. Associated factors with symptom severity of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder (AjD).

The subset analysis of SCT patients revealed no treatment-related associated factors with PTSD and AjD symptoms in univariate regression models, that is, type of SCT, presence of GvHD, and days spent in isolation ().

Discussion

This cross-sectional observational study among hematological cancer patients investigated self-reported symptoms of cancer-related PTSD and AjD according to new diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5 and ICD-11, and associated sociodemographic and medical characteristics. Taken together, one in three patients was identified as having cancer-related PTSD or subthreshold PTSD. More than half reported at least one core symptom cluster of AjD. Treatment with SCT did not affect frequency and symptom severity. We identified subgroups particularly associated with elevated symptoms, that is, younger patients and patients with higher physical symptom burden.

Studies on PTSD among hematological cancer patients are still sparse and mostly based on DSM-IV. Studies using self-report screeners report 8 to 13% and 9 to 35% of the patient’s meeting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD, respectively [Citation28,Citation37,Citation38]. Our results, to be placed in the middle of this range, are thus supported by previous studies. Changes in DSM-5 mainly involve the definition of symptom clusters and numbers of symptoms needed to diagnose PTSD. The self-report screener based on these new criteria has only been applied in two studies with cancer patients so far [Citation25,Citation26], with one among SCT patients showing 3% meeting criteria-based PTSD [Citation26]. Our sample shows a higher rate, possibly explained by additional traumatic events. We investigated all potentially traumatic events during the disease, whereas Liang et al. [Citation26] only assessed PTSD caused by the SCT. We thus extended existing results on hematological cancer patients with insights on PTSD caused by a comprehensive assessment of stressful experiences faced by this group.

Previous research on AjD mainly relies on DSM-IV clinical interviews, which hampers a comparison with the data from self-report screeners. ICD-11 however marks a paradigm shift and AjD is now characterized by symptoms of preoccupation and failure to adapt to the stressor [Citation39]. Research applying new criteria with the self-report screener is very sparse to date. Tang et al. applied the screener and reported 39% of 342 newly diagnosed breast cancer patients suffering from criteria-based AjD, with more than half (56%) elicited by the cancer disease, followed by financial difficulties [Citation8]. Our sample shows less cases of cancer-related AjD, possibly explained as follows. First, we found younger age to increase the risk for AjD. Our sample being older than in the study of Tang et al. might explain differences in AjD. Second, our patients were not newly diagnosed with cancer and adaptation to stressors, development of coping strategies or seeking of support might have decreased AjD in our sample. Our results were based on new criteria and need to be confirmed in future studies.

Very little is known how SCT impacts PTSD and AjD. Even though SCT treatment is related to the type of hematological malignancy, disease prognosis and therefore existing stressors, PTSD and AjD development was neither affected by SCT in general nor type of SCT in our study. To date no study systematically compares all three groups (allogeneic, autologous, no SCT). In line with our results, a study among non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients found no association between SCT and PTSD diagnosis [Citation28], as did a study of 37 breast cancer patients, half of whom underwent autologous bone marrow transplantation [Citation40]. Even though allogeneic and autologous SCT bear distinct stressors, for example, GvHD is common only in allogeneic SCT, type of SCT did not affect PTSD and AjD in previous studies [Citation26,Citation41], which is consistent with our results. Thus, stressors resulting from SCT might not be most prominent and hematological cancer patients already face severely stressful events that may lead to PTSD and AjD. For example, the most frequent distressing event reported is the moment of cancer diagnosis [Citation42,Citation43], also demonstrated in our sample (Springer et al. in review). The diagnosis might be experienced as threat to life, whereas SCT might rather be seen as life-affirming and a “second chance” to survive [Citation40]. In addition, other aspects may be more important explaining vulnerability to traumatic events, such as individual resources to cope with stressful events or social support [Citation44].

Younger age increased PTSD and AjD symptoms in our study. Younger patients are often exposed to additional stressors [Citation45], for example, employment, fertility or financial insecurities, leaving them potentially more distressed and vulnerable to traumatic experiences. Most studies among hematological cancer patients or with comparable screeners support our result [Citation25,Citation28,Citation46]. However, a study among 691 cancer patients reported no association between age and PTSD [Citation26]. They investigated age binary, that is, over and under 60, which may not be sufficient to show this association. Medical variables that increased PTSD and AjD symptoms in our study include stressors with an enduring character, that is, symptom burden from comorbidities and an active disease. Enduring stress might contribute to feelings of helplessness and reduced self-efficacy, which might increase vulnerability to stressful experiences. Previous studies also demonstrated physical comorbidities to increase PTSD and AjD symptoms [Citation25,Citation28], which appeared to be the strongest predictor in our study with medium effect sizes. Remission status was investigated sparsely, showing that active disease increased PTSD compared to patients in remission [Citation28].

Clinical implications

Presence of PTSD and AjD symptoms might lead to high burden and should not go undetected nor untreated. The high number of hematological cancer patients reporting clinical levels of cancer-related PTSD and AjD, as well as subsyndromal symptoms, underlines the necessity to integrate screening into routine clinical care. This may help to appropriately plan and provide effective psychological treatment. Since treatment with SCT did not affect PTSD and AjD, stressors for hematological cancer patients might already be very high and SCT might not be most prominent leading to PTSD and AjD. Further aspects might rather play a role in the development, that is, facing additional physical and psychological stressors or younger age. Patients at risk should be considered particularly for close monitoring to provide them with psychosocial support.

Strengths and limitations

This study is one of the first to assess self-reported PTSD and AjD symptoms based on updated diagnostic criteria in cancer patients, and to investigate the impact of SCT on symptoms. Robust data from the medical records was available, which enabled a valid comparison of patients with different treatment regimes.

Some limitations are to be mentioned. First, since hematological cancer patients show specific stressors, generalization of our results to other nonhematological cancer populations are limited and findings need to be verified. However, since stressors in this patient group are specific, disease-specific analyses are required. Second, PTSD and AjD were assessed via self-report in our analysis and not clinical interviews. The rates might therefore be overestimated [Citation4,Citation21,Citation22] and should be interpreted with caution. However, self-report screeners are particularly relevant in oncology care as they are routinely used by clinicians to determine the severity of symptoms and to consider referral. Results of the clinical interview assessed in this study will be addressed in a separate publication. Third, as some patients did not participate because they felt too burdened or had no interest in the study, there might be a selection bias toward patients being less distressed. Unfortunately, no validated data on psychological distress of non-participants was available. However, participants and non-participants did not differ on sociodemographic and medical variables. Fourth, the cross-sectional design does not allow any causal conclusions regarding the association of PTSD and AjD with patient characteristics, but provides first ideas that need to be tested in confirmatory studies.

Conclusion

A considerable part of hematological cancer patients suffers from PTSD and AjD symptoms according to updated diagnostic criteria. Patients with additional physical and psychological stressors are particularly at risk of developing elevated symptoms. Regular screening of PTSD and AjD symptoms in this group of patients seems necessary, however, results need to be validated in future longitudinal studies.

Author contributions

Conception of the study: PE, AMT, KK, JE, HG. Methodology: PE, AMT, KK, JE, HG, MF, FS. Funding acquisition: PE, AMT. Conception of the Manuscript: FS, PE. Formal Analysis: FS, MF. Data Curation: FS, MF, PE. Investigation: FS, PE, KK, JE, SH. Resources: UP, VV. Supervision: AMT, HG. Writing original draft: FS. Writing–review and editing: all authors. Approval of the final manuscript: all authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, et al. Four-Week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3540–3546. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0086.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X.

- Abbey G, Thompson SBN, Hickish T, et al. A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and moderating factors for cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychooncology. 2015;24(4):371–381. doi: 10.1002/pon.3654.

- Arnaboldi P, Riva S, Crico C, et al. A systematic literature review exploring the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and the role played by stress and traumatic stress in breast cancer diagnosis and trajectory. Breast Cancer. 2017;9:473–485. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S111101.

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: a prospective study. Psychooncology. 2007;16(3):181–188. doi: 10.1002/pon.1057.

- Jacobsen PB, Widows MR, Hann DM, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(3):366–371. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00026.

- Van Beek FE, Wijnhoven LMA, Custers JAE, et al. Adjustment disorder in cancer patients after treatment: prevalence and acceptance of psychological treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(2):1797–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06530-0.

- Tang H y, Xiong H h, Deng L C, et al. Adjustment disorder in female breast cancer patients: prevalence and its accessory symptoms. Curr Med Sci. 2020;40(3):510–517. doi: 10.1007/s11596-020-2205-1.

- Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(8):1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980.

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard‐Zolnierek KB. Impact of depression on treatment adherence and survival from cancer. Depression and Cancer. 2011;101–124.

- Haskins CB, McDowell BD, Carnahan RM, et al. Impact of preexisting mental illness on breast cancer endocrine therapy adherence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;174(1):197–208. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-5050-1.

- Im A, Pavletic SZ. Immunotherapy in hematologic malignancies: past, present, and future. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0453-8.

- Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383.

- Townsend W, Linch D. Hodgkin’s lymphoma in adults. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):836–847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60035-X.

- Danylesko I, Shimoni A. Second malignancies after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19(2):9. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0528-y.

- Al Hamed R, Bazarbachi AH, Malard F, et al. Current status of autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9(4):44. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0205-9.

- Loke J, Buka R, Craddock C. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: who, when, and how? Front Immunol. 2021;12:659595. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.659595.

- Cho SY, Lee HJ, Lee DG. Infectious complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: current status and future perspectives in korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33(2):256–276. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.036.

- Penack O, Marchetti M, Ruutu T, et al. Prophylaxis and management of graft versus host disease after stem-cell transplantation for haematological malignancies: updated consensus recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(2):e157–67–e167. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30256-X.

- Kuba K, Esser P, Scherwath A, et al. Cancer-and-treatment-specific distress and its impact on posttraumatic stress in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT): cancer-and-treatment-specific distress following HSCT. Psychooncology. 2017;26(8):1164–1171. doi: 10.1002/pon.4295.

- Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R27. doi: 10.1186/cc5707.

- Krebber AMH, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, et al. Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta‐analysis of diagnostic interviews and self‐report instruments. Psychooncology. 2014;23(2):121–130. doi: 10.1002/pon.3409.

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, et al. The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059.

- Einsle F, Köllner V, Dannemann S, et al. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15(5):584–595. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.487107.

- Jung A, Crandell JL, Nielsen ME, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors: a population-based study. Urol Oncol. 2021;39(4):237.e7-237–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.11.033.

- Liang J, Lee SJ, Storer BE, et al. Rates and risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology among adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and their informal caregivers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(1):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.08.002.

- O'Connor M, Christensen S, Jensen AB, et al. How traumatic is breast cancer? Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and risk factors for severe PTSS at 3 and 15 months after surgery in a nationwide cohort of danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(3):419–426. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606073.

- Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, et al. Post-traumatic stress outcomes in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(6):934–941. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3414.

- Mosher CE, Redd WH, Rini CM, et al. Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2009;18(2):113–127. doi: 10.1002/pon.1399.

- Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22(4):499–524. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00118-0.

- Esser P, Kuba K, Ernst J, et al. Trauma- and stressor-related disorders among hematological cancer patients with and without stem cell transplantation: protocol of an interview-based study according to updated diagnostic criteria. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):870. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6047-9.

- Krüger-Gottschalk A, Knaevelsrud C, Rau H, et al. The german version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):379. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1541-6.

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Friedman MJ, et al. Subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.028.

- Glaesmer H, Romppel M, Brähler E, et al. Adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11: dimensionality and symptom differentiation. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(3):940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.010.

- Lorenz L, Bachem R, Maercker A. The adjustment disorder–new module 20 as a screening instrument: cluster analysis and cut-off values. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2016;7(4):215–220. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2016.775.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155.

- Varela VS, Ng A, Mauch P, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma: prevalence of PTSD and partial PTSD compared with sibling controls: PTSD in survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Psychooncology. 2013;22(2):434–440. doi: 10.1002/pon.2109.

- Liu L, Yang YL, Wang ZY, et al. Prevalence and positive correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among chinese patients with hematological malignancies: a cross-sectional study. PLOS One. 2015;10(12):e0145103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145103.

- O’Donnell ML, Agathos JA, Metcalf O, et al. Adjustment disorder: current developments and future directions. IJERPH. 2019;16(14):2537. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142537.

- Mundy EA, Blanchard EB, Cirenza E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in breast cancer patients following autologous bone marrow transplantation or conventional cancer treatments. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(10):1015–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00144-8.

- Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1907–1917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.101.

- Mehnert A, Lehmann C, Graefen M, et al. Depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and health-related quality of life and its association with social support in ambulatory prostate cancer patients: depression and anxiety in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(6):736–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01117.x.

- Green BL, Rowland JH, Krupnick JL, et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(2):102–111. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71356-8.

- Jacobsen PB, Sadler IJ, Booth-Jones M, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology following bone marrow transplantation for cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(1):235–240. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.235.

- Quinn G, Goncalves V, Sehovic I, et al. Quality of life in adolescent and young adult cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:19–51. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S51658.

- Fenech AL, Van Benschoten O, Jagielo AD, et al. Post-Traumatic stress symptoms in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Transplant Cell Ther. 2021;27(4):341.e1–341.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2021.01.011.