ABSTRACT

We examine the gap between theory and practice in social accountability mechanisms to improve local governance performance in Tanzania. We do so through drawing on an ethnographic investigation tracing lines of blame and responsibility for service delivery, from individual citizens up to the central state incorporating a total of 340 interviews and 12 focussed group discussions. We have two keys findings: Firstly, that there is a wide divergence between formal lines of accountability and where actors direct blame for performance failure in practice. Secondly, building a collective understanding of this divergence provides an effective starting point for intervention to improve performance. Our conclusion is that dominant assumptions on social accountability interventions require significant revision in light of our findings.

Introduction

Shabani is a government water officer in a Tanzanian District office and has been employed for 15 years. He knows there are national water policies, and they sound good on paper, but there appears to be little activity happening at the District level. Sometimes, when a donor is interested, there is a flurry of activity. In some villages too, there are NGOs who seem to be doing something when they have money, but he is not sure what. He has been to countless public meetings in villages where they tell him that they need an improved water supply, but every village says this and what is he supposed to do? Last year was an election year and his department only received 10% of their allocated budget. There was no money to do anything, sometimes salaries were delayed. He wants to do his job and improve services. His family live in a water-scarce village but he is stuck in the system.

Where should the blame lie for this inertia and who is responsible for taking action? Is it the fault of the central government for not giving him the resources he needs to do his job? Is it the fault of the District councillors for not prioritising spending on water projects, and for not organising the villagers to make contributions? Perhaps there is the money going missing through corruption. Perhaps he should blame the villagers as they seem to expect that the government will just come and do everything for them. Perhaps he should blame himself for not being proactive enough.

Many donor-funded social accountability projects and programmes start from the assumption that citizen action is required to hold the state to account and drive the effective delivery of public services (Fox Citation2015; Joshi Citation2014; Mdee and Thorley Citation2016a, Citation2016b). With this assumption, a lack of progress on service delivery might be framed as being caused by corruption within the system, a lack of proper institutional mechanisms and policies, or inertia and apathy on the part of office holders. The social accountability answer is to create mechanisms to ‘shout at the system’ underpinned by the assertion that citizens hold rights to services and they can and should organise to use their collective voice to demand action for improvement. Collective citizen voice is then transmitted to the system through a civil society organisation that can lobby office holders to demand action. Literature on public participation, citizen action and social accountability have long made clear that such assumptions are overly simplistic (Carothers and De Gramont Citation2013; Fox Citation2007, Citation2015, Citation2016; Joshi Citation2014, Citation2017; Mansuri and Rao Citation2013); nevertheless, they frequently appear in the everyday discourse of NGOs, and their projectsFootnote1 (Tembo and Chapman Citation2014, Citation2017).

For such social accountability mechanisms to function then lines of responsibility, and therefore, blame for failure would need to be clear. In theory, responsibilities are set out in national policies, but there is often a gap in the extent to which such policies are/can be implemented (Wild et al. Citation2015; Andrews Citation2015; Mdee and Thorley Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c). It therefore cannot be assumed that responsibility for the delivery of public services is commonly understood and agreed by all actors.

This article argues that narratives of responsibility and blame-avoidance matter for social accountability to function and that interventions to improve local governance and service delivery must be built on actual rather than idealised conditions and relationships. It is necessary to understand the gap between policy on paper (e.g. on how planning processes work) and how they operate in practice in order to facilitate effective processes of improvement.

There are three parts to the paper: Firstly, we show why mapping narratives of blame and responsibility are a critical starting point for working out how to improve local governance and service delivery. Secondly, we apply Hood’s concept of ‘blameworld’ (Hood Citation2010) to map lines of responsibility and blame in two Districts in Tanzania, drawing on an extensive ethnographic dataset. Finally, we argue that this research shows that more effective social accountability programmes should be based on a detailed understanding of how local governance actually works, rather than on idealised constructs of ‘citizens’ holding ‘government’ to account.

Untangling blame and responsibility in social accountability

Social accountability mechanisms often start with the principle of informed rights holders seeking enactment of responsibilities as set down in policy or legislation. Such an approach assumes clearly identifiable duty bearers and rights holders, and specifically that when public services or rights are not realised that blame and responsibility are obvious, and action can be demanded. This assumption fundamentally requires that blame and responsibility can be ascribed to actors that can be compelled, through citizen demand, to change their behaviour. However, responsibilities are often relatively undefined and diffuse. Such foundational assumptions of social accountability are increasingly contested but remain common in international development practice (Fox Citation2007, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018; Hickey and King Citation2016; Joshi Citation2014, Citation2017; Tembo and Chapman Citation2017).

These critiques of the practice argue that much (but certainly not all) social accountability work remains rooted in isolated ‘tactics’ such as tool led interventions (e.g. scorecards), information provision, and localised citizen voice activities; as opposed to a more strategic approach involving multiple and co-ordinated tactics, enabling environments for collective action to reduce risk, citizen voice co-ordinated with governmental reforms, multi-level, iterative and contested campaigns not limited interventions (Fox Citation2015; Tembo and Chapman Citation2017).

We suggest that a more strategic approach to social accountability might start with understanding lines of blame and responsibility in local governance and public service delivery. This is more than creating and ascribing blame to particular actors and institutions, but is about identifying multiple, conflicting and shifting lines of responsibility for action and where blame falls for failure. This tell us much about the perceptions, narratives and positions of the actors within local governance and public service delivery systems. A formal policy may set out clear lines of accountability and how they should operate in theory, but narratives of responsibility and blame describe how governance works in practice, and yet have been significantly under-theorised or examined (Olivier de Sardan Citation2011)

Hood suggests: ‘… blame-avoidance is a descriptive account of a force that is often said to underlie much of political and institutional behaviour in practice’ (Hood Citation2007, 192).

There is little literature examining blame in relation to international development and institutional reform in Southern countries. It has received some examination in relation to direct and diffuse responsibility for the achievement of internationally negotiated benchmarking mechanisms such as the MDGs (Clegg Citation2015) but there are very few examinations of blame and responsibility within across decentralised systems. A notable exception here being a study on environmental governance in China (Ran Citation2017).

Bringing in blameworld

Blame can be used to make claims on actors and institutions but blame avoidance can be also used to sidestep and obfuscate responsibility. Understanding blame avoidance and blame shifting help us to identify lines of power and barriers to change.

Hood (Citation2010) argues that within governance systems there are a number of worlds, and within these worlds, individuals and systems who each can play strategies of shifting blame upwards, sideways, downwards and outwards. In his work on blame avoidance in Northern Governments, he identifies significant players as the top bananas, street-level bureaucrats, the middle managers, and civil society as set out in . Players can (depending on their position) shift blame upwards, downwards, sideways or outwards, with strategies of blame avoidance rooted in three main types of blame-avoidance resources:

Presentational – shaping the narrative, e.g. through media engagement

Agency – distribution of formal responsibility to multiple actors, so as to diffuse responsibility

Policy – selection of policy or operational procedures to reduce risk of blame, or to shift blame

Table 1. Blameworld: four sets of players and their strategies (Hood Citation2010, 42)

Strategies of blame avoidance that can be deployed vary according to context and rituals of power in particular instances (Resodihardjo et al. Citation2016). Cultures of blame avoidance can also shift over time, for instance, Baekkeskov and Rubin (Citation2017) describe how China has shifted from an environment of secrecy to one of employing ‘lightening rods’ to absorb and shift blame. Rwanda’s preference for centralised control and the use of performance (imihigo) contracts for public servants have created an environment where lines of blame are carefully defined by the state (Gaynor Citation2014; Purdeková Citation2011)

Blame and blame avoidance also relate to cultural specificities of shame. Formal systems of accountability that expect public officials to be held responsible for poor service delivery might seek to shame officials or institutions into performing to a certain expected standard, for example, through a public expenditure tracking exercise. Both blame and shame speak to ideas of moral and just behaviour on the part of the individual. It could be that where there is a high degree of dissonance between how systems are supposed to work in theory, and how they work in practice; that this is also associated with dissonance in how an individual office-holder is expected to behave. For example, the payment, by a service user, of an unofficial fee (a bribe) to a public official in order to jump a queue is normatively how a system might operate in practice, and is widely seen by service users as legitimate,after all that official has to supplement their low salary and their wider family network will benefit from that. Ekeh’s conceptualisation of the two publics in Africa is pertinent here, and reminds us that blame and shame are contested and shifting; and maybe constituted differently depending on the perceptions of the observer (Ekeh Citation1975; Goddard et al. Citation2016; Osaghae Citation2006).

Method

Mapping dynamics of blame and responsibility is necessarily a complex multi-level process requiring engagement with citizens, non-state actors and government actors across all levels. This draws on phase 1 of a 3-year action research projectFootnote2 that sought to create a local governance performance index (LGPI) in Tanzania through a co-design process with local government and civil society stakeholders. An index and set of baseline data were created in two Districts (Mvomero and Kigoma-Ujiji) from 2014 to 2017 (Mdee, Tshomba, and Mushi Citation2017)). The two Districts were selected by the research teamFootnote3 in order to test the co-design approach in one rural (dominant political party) area and one urban (opposition party) area.

Phase 1 of the project began with an aim to map the gap between how local governance and service delivery were stated to operate in theory (in policy documents), and how it operated in practice. The research team included experts from across the social sciences (sociology, anthropology and economics) and this informed the choice of a two-stage methodological approach. A qualitative ethnographic exploration of accountability for local service delivery was selected in order to reveal multiple narratives and positions across different actors and the level of government (Lee Citation1999). Phase 2 followed later followed a process of coding and refining this data to produce a quantitative local governance performance index. However this paper focusses only on phase 1. Open-ended discursive interviews were framed around the question of ‘who is responsible for local service delivery?’, ‘who is responsible for improving services?’ and who is to blame for a lack of improvement/problems’? Interviewees were also asked to reflect on their own roles or participation in local governance mechanisms. Interviewees were all conducted in Swahili by members of the research team employed by Mzumbe University. Interviews were sequenced to gradually build emergent narratives from the lowest unit of government (the village). Villages/streets were purposively selected to cover different profiles of livelihoods in the District. Twenty-five citizens, purposively selected for gender and age were interviewed in each location (giving a total of 200 citizens), along with all village/street elected representatives and village/street local government employees. Key informant interviews with other selected actors such as the staff of civil society organisations and religious leaders were also included. This process then tracked upwards to include ward and district level staff and political representatives, and civil society representatives, and finally within the Ministries of the central government and head offices of significant civil society groups. A total of 340 interviews was conducted in 2015.

The qualitative data were analysed thematically by the core research team during a two-day analytical workshop in Kigoma in December 2015, firstly in relation to responsibility for improving governance and service delivery; and secondly, in relation to specific attributes of different service areas of local government (the necessity of this differentiation is shown in Batley and Mcloughlin Citation2015). Findings were also triangulated through reference to existing research on local governance in Tanzania. Additional validation activities were undertaken in both districts during phase 2 of the project after the local governance index was fully designed and tested (Mdee, Tshomba, and Mushi Citation2017). The results discussed below relate to the analysis undertaken in phase 1. Thematic coding was applied across the stratified interview data set. All members of the core research team read full interview transcripts and highlighted answers to the questions outlined above. This was done in the same order as the interviewees were conducted and therefore gradually constructed a complex mapping of narratives of responsibility and blame. The analysis done by the core research team was further refined through a validation and triangulation process at the district level by stakeholders from all levels of government, as well as citizens and representatives of civil society through 12 focussed group discussions during early 2016.

Results and discussion

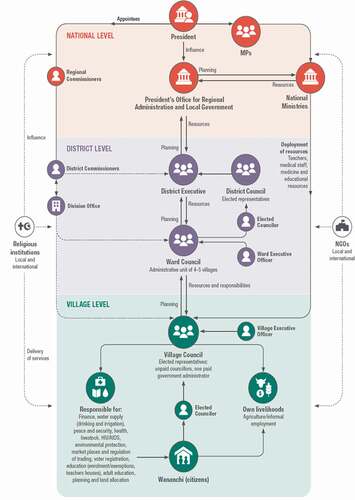

In our interviews, all appointed and salaried civil servants in the Tanzanian government system articulate the local development planning process as it is set out in the policy. Since 1999 the Tanzanian Government actively pursued an incremental strategy of what is referred to as, ‘Decentralization by Devolution’ (DbyD). This relates to the transfer of power and authority from central government to subnational tiers of government and based on the principle of subsidiarity. ‘Local governments through their elected leaders have a responsibility for social development and public service provision within their areas of jurisdiction; facilitation of maintenance of law and order and promotion of local development through participatory processes’ (Muro and Namusonge Citation2015, 106). Participation is expected to ‘empower’ citizens and supports Nyerere’s concept of self-reliance, that participation by citizens is an obligation to build the nation (Muro and Namusonge Citation2015). Therefore, participation by citizens is not only in giving their opinions in village/street-led planning processes, but in the expectation of contributing their labour and finance for community development initiatives, such as school classroom building (Tidemand et al. Citation2008). Civil society organisations are viewed as an integral to this process, as a conduit for citizen's voice, holding government to account and through enabling participation in projects aimed at ‘development’ (Mercer Citation2003; Green Citation2014). shows the maps of this system: showing how development planning decisions are designed to flow from the village/street level to be aggregated into District plans and are then communicated to Central government ministries for resourcing. The figure also captures how elected representatives at village, ward and national levels relate to the different levels of government executive.

Decentralisation in practice – responsibility and blame

In practice, the data show that decentralisation is incomplete, contested and ineffective. This is not a new finding but reconfirms previous studies, e.g. Lange (Citation2008). sets out the ‘d by d’ system and shows a central column with planning being driven from the village/street level through the citizens (wananchi) and their elected representatives, and resources flow back down according to the plans. In practice, the flow of resources seldom matches the agreed plans. Regional and district commissioners also exert considerable power over the process of resource allocations and report directly to the president. This is an additional and parallel power structure that remains embedded in the politics of the ruling party, CCM.

According to respondents at these levels, initiatives aimed at strengthening local government or tackling accountability from the local to a national level often focus on the district. Yet, the district sits above many layers of local government (Division-Ward-Village, and in some areas the sub-village designation of Hamlet and 10 cells (10 households)) before the individual citizen. These levels of government are often physically far removed from district administrations. There is also a blurring of lines of responsibility in some sectors in relation to the central and local government powers, particularly in health and education.

Despite rhetoric of decentralisation the central government still exerts significant control over local service delivery through the allocation of resources and policy (Chaligha, Henjewele, and Kessy Citation2007; Chaligha Citation2014). Tidemand et al. (Citation2015) note there are clear inequalities in the distribution of funds from central government and patterns of favouring districts with prominent MPs is evident.

shows that considerable responsibility for governance and service delivery is placed on the village level and on citizens themselves through their volunteer labour or financial contributions (Boesten, Mdee, and Cleaver Citation2011; Green Citation2014). The decentralisation of service delivery can also lead to elite capture at the local level and even to increased inequality in access for the poorest (see, e.g. Cleaver and Toner Citation2006 on the water sector). The ward, village and street levels of government responsibilities include peace and security, land allocations, social welfare and social service delivery, water, economic development, HIV/AIDS, environment etc. Yet the capacity of government at this level is very limited. There is one paid office at the village/street level (the Village/Street Executive Officer), which works in conjunction with unpaid citizen councillors.

Our data set illustrates that the majority (84%) of citizens are uncertain over responsibility and accountability for effective governance and service delivery. Governance and service delivery are consistently referred to as maendeleo (development) in interviews.

Development requires taking out some levels in the leadership hierarchy. The hierarchy is composed of the Member (Mjumbe), the Street Chairperson (Mwenyekiti wa mtaa), the Village or Street Executive Officer (Mtendaji wa mtaa/kijiji), the Ward Executive Officer (mtendaji wa kata) and then the Ward Councillor. This long chain of hierarchy levels generates an environment subject to corruption rather than generating performance because all these people in the leadership chain are actually playing the same role. Interview, male, Kigoma

As a result, citizens had little awareness of what they should expect of local government at any level, as this quotation asserts:

To my knowledge, the role of a councillor is to lead people in all development issues such as road and hospital construction, water supply and so on. I don’t know if this lady (elected councillor) was fulfilling her role as she was supposed to, because in X there is no clean water, nor electricity, nor good road. I don’t know anything about the MP of my area because I’ve never saw him anywhere and I don’t know what the responsibility of an MP is Interview, male, Mvomero

As with responsibility for the development, we found many different views on who should be responsible for holding local government to account. Around 25% of the participants in the research believed that citizens are responsible for holding elected leaders to account; however, the data suggest a wide diversity of opinions on where responsibility should lie including as illustrated by the following quotations:

The one who is responsible for holding local government to account is the citizen, because the citizen is the one who discovers the weakness of his/her leaders. After discovering or seeing a weakness, a citizen has the right to present it for action in the village meeting … Citizens should report their councillors and MPs to the village office, ward office or district council offices. Citizens have full mandate to hold their leaders to account. Participant, focus group with village leaders, Mvomero

The one who is responsible for holding MPs and councillors to account is the chairperson of the CCM (ruling party) because these leaders are under that political party. Participant, focus group, Mvomero

The district commissioner (DC). Why the DC? Because he is a leader of all local government leaders such as councillors, ward executive officers (WEOs), Mtaa executive officers (MEOs),Footnote4 street chairpersons and street members of committees. Participant, focus group, Kigoma

There was recognition of the inter-dependency between different levels and functions when it comes to the ability to perform:

It is difficult for the councillor and MP to do good work or perform their duties and responsibilities well if the lower level (from Kitongoji level to village level) does not perform well. Participant, focus group with village leaders, Mvomero

We need to hold lower-level leaders like the village chairperson to account before holding councillors or MPs to account. Participant, focus group with females, Mvomero

Civil servants also frequently expressed their frustration in interviews:

There are too many bosses who are supervising us … civil servants’ accountability is affected by availability of many supervisors who in one way or another have different opinions and decisions regarding resources. These bosses include ministers, permanent secretaries, regional commissioner, regional administrative secretary, district commissioner, district administrative secretary, members of parliament, councillors and the secretary of the leading party (CCM). Participant, Focus group with local officials, Kigoma

Elected representatives, in theory, could be held to account through the election process. However, the research also revealed concerns amongst citizens about taking action against elected representatives. Fear of reprisal, security, education, personal relationships, and power dynamics were cited as obstacles to such action:

The system means is not easy to remove them once they are elected. The community keeps silence when the leaders do not do what they are supposed to do. Participant, focus group with CSOs, Mvomero

We are the ones who elect them but we don’t know how to hold them to account, we don’t know the procedure that we can use to hold them to account. Participant, focus group, Mvomero

Mechanisms for accountability exist in policy, with officials in focus group discussions outlining clear procedures that exist in law, but in practice, most respondents are not using them or they do not function:

Village leadership is answerable to the Village Assembly. Things are not moving because there is no accountability. The Village Assembly is not the platform to hold leaders to account and accountable, instead village’s leadership use them to give directives. There is no room for engaging in dialogue and discussion. Many leaders and civil servants are not delivering, and instead of citizens using the system and available room to demand for accountability they keep complaining and whining. Interview, Senior official, Unit in the Ministry of President’s Office, Regional Administration and Local Government (PORLAG)

Our village chairperson used to call meetings, but he does not appear in those meetings, how can we hold him to account, while he is not attending village meetings? Participant, focus with village leaders, Mvomero

In reviewing the multiple narratives in the dataset, it was evident that blame shifting of responsibility for problems was occurring between levels of government, and between government and other stakeholders. This analysis was tested and verified by stakeholder reference groups in each of the Districts.

District government – shifting blame up, down and out

This is the level of government on which most responsibility for service delivery is channelled. At this level, lack of progress and problems of service implementation, blame flows both up and down. The central state has in effect enacted a partial decentralisation: whilst many service delivery responsibilities are devolved to the Districts, the resources flows do not match requirements, or even planned allocations. Reliability, availability and timeliness of funds came up again and again with district officials:

The disbursed funds from the government are not enough and neither the revenue collected from own sources within the council. Government funding is never enough and even when it is disbursed it is not on time to carry out activities as planned. The Government prioritizes several big spending projects, all to be done at the same time or within a short period of time. Also, most of them are politically motivated and sometimes not in the plan for the annual spending. Interview, local government official, Kigoma

Local ward councillors are also blamed for their failure to mobilise the people:

The elected are not doing what they are supposed to do and sensitise the citizens to contribute properly to “development” Focus group, Mvomero.

NGOs were blamed for not working with the efforts of the District and so contributing to fragmentation and duplication of efforts. Blame was therefore is enacted outwards, with operational and organisational mechanisms put in place to check the activities of NGOs.

Local leaders- citizens or government?

At the village/street level service delivery and citizen representation functions appear blurred. Most officials and representatives are unpaid yet fulfil many formal functions across health, education, social services, justice and security, environment and livelihoods, but with very limited resources. So, should they be viewed as part of the government or as citizens? To all intents and purposes, Tanzania still operates as a one-party state and therefore citizen leaders are expected to deliver the agenda of the central government.

Elected councillors felt unfairly blamed by citizens. They are aware that if their respective constituencies see no progress, they could be blamed for that. However, they expressed that they struggled to be effective because they do not get paid (blame shifted upwards):

The council chairperson comes into the office twice a month and this is because they are not paid, but the Village Executive Officer and Ward Executive Officer come in every day … The councillors are supposed to be the supervisors of the VEO and WEO but we don’t get our 350,000 TZs salary in time. It can take up to a year to get our money so it gets to the point that we come into the office but we are not happy and we cannot work effectively. Participant, focus group with councillors, Mvomero

Further, councillors reported poor communication and awareness amongst stakeholders. Both district officials and councillors blamed NGOs for lack of cooperation (blame shifted outwards). It was reported in focus groups that NGOs sometimes bypass the village leadership when they bring citizen complaints to the district level.

Wanachi (Citizens)- rights bearers or the problem?

Decentralisation by Devolution (DbyD) includes the idea that participation will ‘empower’ citizens. This also supports Nyerere’s concept of self-reliance, where participation is an obligation if one is to build a nation (Green Citation2000, Citation2003, Citation2014). This self-reliance concept has led many villagers, as well as the local and central government, to believe that villagers are the ones who are responsible for bringing development through volunteer labour or financial contributions:

Villagers are the source of development. No one else can bring development within the village except villagers themselves. If we need a road, we will build it ourselves. If we need a school, we will build it ourselves. The government is not capable of bringing development to villagers. The government cannot do each and everything. Villagers are responsible to educate themselves and not wait for others to come and educate them. If we stay in that situation, we will keep complaining that life is harder and that there is no development. Female elder, Mvomero

Therefore, we see, that the downwards blame shifting that runs from central government is internalised at the village level, and many citizens cast blame sideways for a failure to deliver ‘development’.

Whilst citizens and village leadership are given, and give themselves, a central role in delivering development, there is an expectation that local government, MPs, and the President will play their part:

The responsibility to reduce poverty lies with our leaders – councillors, MP and Ministers – because these individuals know a lot about peoples’ problems. Thus, they are required to use all national resources properly and avoid fraud over government funds and embezzlement of funds. Interview, male, Mvomero

The one who is responsible to bring development to people is the government because all source of revenues are owned by the government. Interview, male, Kigoma

NGOs- many actors and many lines of blame

NGO participants in focus groups claimed that politicians do not take action on problems facing citizens. Councillors were perceived as not taking peoples’ views seriously and not cooperating well with NGOs; they had more interest in getting allowances than in developing their wards (constituencies):

There is a need to hold local government (councillors and MPs) to account, because they don’t perform their duties properly (poor efficiency); for example, our MP has not been to visit us since we elected him even to give greetings. Our MP has confused us very much because we see him go to the parliament, but he doesn’t come to visit us here; what things does he say in the parliament? Participant, focus group, Mvomero

The leaders can be told they are not doing their jobs in the village meetings. Some of the village leaders do not attend meeting and even when they attend, they don’t take it seriously – they do not ask questions. Participant, focus group, Mvomero

Participants said that poor accountability was caused by the absence of a platform to bring together representatives, the government and NGOs to share knowledge and experience. They suggested blame lies with weak co-ordination functions in the District Council.

NGO focus group participants noted that many elected leaders did not have access to the necessary information. For example, education coordinators had no information on national education policy and therefore were not aware of what it entailed:

Elected local leaders sometimes do not know their responsibilities and this has been due to absence of well-structured guidelines and strategies to bring about people’s well-being, such as nutrition, health and education. Participant, focus group, Kigoma.

Mapping ‘blameworlds’

In order to make sense of these multiple lines of blame, the research team mapped organising the data using Hood’s notion of blameworld as shown in . This allows us to identify narratives of blame and blame avoidance as properties of different sets of agents.

Table 2. Blameworlds in Tanzanian governance

Public policymaking in Tanzania is shaped by external pressures from the normative agendas of aid agencies, and internal political dynamics. The large bilateral and multilateral development agencies operate in a blameworld that emphasises reform of institutions, and creation of policies that articulate normative development agendas, such as the SDGs. Therefore, official policies are often designed to address these agendas, rather than the particularities and capabilities of the Tanzanian context and rely on an assumption of aid-supported implementation (Green Citation2000, Citation2014; Mdee and Harrison Citation2019).

At the same time, the central state deploys a strong public discourse of blame for failures and lack of progress in public service delivery on its own uneducated and backwards population. This population is seen to require sensitisation on how to become developed. Development (maendeleo) as a hermeneutic concept has a significant cultural life of its own in Tanzania (Green Citation2014), and the state has deployed this language since independence to condition political and individual behaviour. See, for example Maghimbi (Citation2012) who blames parents for not paying more for education, as a reason for poor outcomes in the education system. The special narrative history of development/maendeleo thus shapes blame and responsibility discourse, and plays a strong cultural role placing responsibility on citizens themselves to deliver maendeleo. Maendeleo has become a normative mission of the state and is imbued with the presumed attitudes and behaviours of modernity, that will deliver advanced infrastructure (roads, hospitals, schools), institutions (export markets, bureaucracy) and materially improved livelihoods (cars, TVs, adequate food) (Green Citation2014; Mdee et al. Citation2019; de Bont, Komakech, and Veldwisch Citation2019).

In the recent authoritarian turn in Tanzanian politics, since the election of John Pombe Magufuli, political opposition has been supressed as it is blamed for distracting the state from delivering ‘development’. Magufuli is overtly using a presentational strategy that visibly targets corruption in public institutions, through the removal of ‘ghost workers’, public dismissals of leaders and rousing speeches to the public.Footnote5

The central state has in effect enacted a partial decentralisation: whilst many service delivery responsibilities are devolved to the districts, the resource flows seldom meet planned allocations (Lange Citation2008; Mdee and Thorley Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Problems with the reliability, availability and timeliness of funds came up repeatedly with district officials, as a reason for the lack of improvement in public services, but in an authoritarian and hierarchical culture, it is difficult to be overtly critical of the upper layers of the state bureaucracy. Ran’s (Citation2017) work on the failure of decentralised environmental governance in China would make an interesting comparative study here.

The districts have few resources for presentational strategies of blame avoidance and predominantly echo the central government playbook: ‘maendeleo requires modernisation, we need resources to do this, people must be sensitised to play their role in creating development’. Therefore, the elected representatives of the people (ward councillors), are also blamed for their failure in mobilising the people to contribute properly to ‘development’.

At the village/street level service delivery and citizen representation functions appear blurred. Most officials and representatives are unpaid yet fulfil many formal public functions across health, education, social services, justice and security, environment and livelihoods. So, should we view them as part of the government or as citizens? To all intents and purposes, government in Tanzania still operates as a one-party state and therefore citizen leaders are expected to deliver the agenda of the central government. Therefore, citizens are servants of the central state, exactly counter to the expectations of social accountability mechanisms which ask the citizen to hold the state to account.

The self-reliance concept has led many citizens, as well as the local and central government, to believe that citizen are the ones who are responsible for bringing development through volunteer labour or financial contributions, and their failure to do so is caused by selfishness, the breakdown of society or even the influence of the socialist past where people expect the government to do everything for them.

The idea that NGOs will hold the government to account for service delivery in this space is problematic. Whilst the literature shows examples of NGOs mobilising citizens to demand that public servants deliver on their promises (Mdee and Thorley Citation2016a). Such projects tend to exist as time-limited responses to opportunities to access donor funding and have a little lasting impact on the public space in Tanzania (Beckmann & Bujra Citation2010; Mdee and Thorley Citation2016b) and are becoming increasingly difficult in the increasingly authoritarian public space in Tanzania. Some NGOs representatives, and particularly those who have participated in governance and accountability workshops have imbibed the donor-driven social accountability blame narrative: that the citizen needs to hold the government to account, through naming and shaming strategies. At the same time, NGOs echo the same top-down narrative of blame that points to the ‘uneducated’ and dependent citizen for a lack of progress in service delivery.

Organising visual representation of the different ‘blameworlds’ in operation in this space reveals previously hidden dynamics of blame and allows open discussion of them. This analysis was used as the starting point by stakeholder working groups in phase 2 for the design of a local governance performance index, as it enabled the different actors involved (District officials, elected representatives, NGO representatives) to discuss the actual complexity of local service delivery problems and performance. This analysis was also refined and validated by village-level interviewees during their participation in phase 2 design work.

The ethnographic method mapped lines of blame in cooperation with stakeholders across the governance system. The aim of doing so was not to apportion blame but to identify how blame was used to shift responsibility and to obfuscate responsibility. We found that this process created a neutral space to discuss blame and failure, and therefore to start to discuss problems and blockages in service delivery. This enabled different groups of stakeholders to step away from their official scripts, in which they couch failure in terms of non-compliance with the ideals of official policy, and to address what is actually occurring in the local governance space.

Conclusion

That citizens should hold the government to account to deliver their rights to services is a powerful idea in the international development industry. Yet such ideals are extremely difficult to implement in practice even where it appears that citizen-led planning processes are part of formal government policy. Our work shows that whilst on paper Tanzania has a citizen-centred and bottom-up decentralised development planning process; in practice, the system functions in a top-down and hierarchical manner with significant blame for lack of progress directed at citizens themselves. It has generated a system where energy is focused on blaming other actors for failure/inertia and avoiding responsibility for improvement. Building a collective understanding between local stakeholders (government, elected representatives and civil society) of how blame was being shifted proved a valuable starting point for a realistic discussion on how to address improvements in governance and service delivery. We argue that this is a far more effective starting point for social accountability intervention than the fantastical and abstract notion of the ‘citizen’ shouting at the system to demand their ‘rights’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Mdee

Anna Mdee is Professor of the Politics of Global Development at the University of Leeds, UK. Her research interests include water, livelihoods, local governance, aid, and sustainable agriculture. Her recent work focuses on inclusive local governance in Tanzania, creating and tracking the evolution of a local governance performance index. She also leads the policy and governance workstream of the UKRI GCRF Water Security and Sustainable Development Hub.

Andrew Mushi

Andrew Mushi lectures in governance and development at Mzumbe University, Tanzania. His research focuses on governance, democracy, social movements, public policy, and civil society. His recent work focuses on inclusive local governance in Tanzania, creating and tracking the evolution of a local governance performance index. He also leads the Tanzania Hub of Knowledge for Change (K4C), a UNESCO initiative training mentors and leaders in community-based research.

Notes

1. See for example the Oxfam Chakua Hatua Programme in Tanzania https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/the-chukua-hatua-accountability-programme-tanzania-338436.

2. This project ‘Holding local leaders and local service provision to account: the politics of implementing a local governance performance index; (ES/L00545X/1)was funded by the UK Department for International Development/Economic and Social Research Council Poverty Alleviation Research Programme from 2014–17.

3. A coalition of researchers led by Anna Mdee and Andrew Mushi of Mzumbe University with Imran Sherali of Foundation for Civil Society, Rachel Hayman of INTRAC, Andrew Coulson of Birmingham University working with stakeholder reference groups (made up of local government office holders and civil society representatives) in each District.

4. The MEO fulfils the same functions as the Village Executive Officer, but is present in urban areas.

References

- Andrews, M. 2015. “Doing complex reform through PDIA: Judicial sector change in Mozambique„. Public Administration and Development 35 (4): 288–300.

- Baekkeskov, E., and O. Rubin. 2017. “Information Dilemmas and Blame-Avoidance Strategies: From Secrecy to Lightning Rods in Chinese Health Crises.” Governance 30 (3): 425–443. doihttps://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12244.

- Batley, R., and C. Mcloughlin. 2015. “The politics of public services: A service characteristics approach.„ World Development 74(2015): 275–285.

- Beckmann, N., and J. Bujra. 2010. “The ‘Politics of the Queue’: The Politicization of People Living with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania.” Development and Change 41(6):1041–1064. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01672.x.

- Boesten, J., A. Mdee, and F. Cleaver. 2011. “Service Delivery on the Cheap? Community-based Workers in Development Interventions.” Development in Practice 21 (1): 41–58. doihttps://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2011.530230.

- Carothers, T., and D. De Gramont. 2013. Development Aid Confronts Politics: The Almost Revolution. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

- Chaligha, A. E. 2014. “Transparency and Accountability in Local Governance in Tanzania.” REPOA Brief. Research on Poverty Alleviation (REPOA). https://www.africaportal.org/publications/transparency-and-accountability-in-local-governance-in-tanzania/

- Chaligha, A. E., F. Henjewele, and A. Kessy. 2007. “Local Governance in Tanzania: Observations from Six Councils 2002–2003.” Research on Poverty Alleviation (REPOA). January 1. https://www.africaportal.org/publications/local-governance-in-tanzania-observations-from-six-councils-2002-2003/

- Cleaver, F., and A. Toner. 2006. The Evolution of Community Water Governance in Uchira, Tanzania: The Implications for Equality of Access, Sustainability and Effectiveness. 30 vols. Natural Resources Forum.

- Clegg, L. 2015. “Benchmarking and Blame Games: Exploring the Contestation of the Millennium Development Goals.” Review of International Studies 41 (5): 947–967. doihttps://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210515000406.

- de Bont, C., H. Komakech, and G. J. Veldwisch. 2019. “Neither Modern nor Traditional: Farmer-led Irrigation Development in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania.” World Development 116(2019):15–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.11.018.

- Ekeh, P. P. 1975. “Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 17 (1): 91. doihttps://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500007659.

- Fox, J. 2007. “The Uncertain Relationship between Transparency and Accountability.” Development in Practice 17 (4–5): 663–671. doihttps://doi.org/10.1080/09614520701469955.

- Fox, J. 2015. “Social Accountability: What Does the Evidence Really Say?” World Development 72: 346–361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011.

- Fox, J. 2016. Scaling Accountability through Vertically Integrated Civil Society Policy Monitoring and Advocacy. Brighton. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/123456789/12683

- Fox, J. 2018. “The Political Construction of Accountability Keywords„. IDS Bulletin 49 (2): 65–80. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/13680/IDSB492_10.190881968-2018.136.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Gaynor, N. 2014. “‘A Nation in a Hurry’: The Costs of Local Governance Reforms in Rwanda.” Review of African Political Economy 41: 549–563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2014.976190.

- Goddard, A., M. Assad, S. Issa, J. Malagila, and T. A. Mkasiwa. 2016. “The Two Publics and Institutional Theory – A Study of Public Sector Accounting in Tanzania.” Critical Perspectives on Accounting 40: 8–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2015.02.002.

- Green, M. 2000. “Participatory Development and the Appropriation of Agency in Southern Tanzania.” Critique of Anthropology 20(1):67–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X0002000105.

- Green, M. 2003. “Globalizing Development in Tanzania: Policy Franchising through Participatory Project Management.” Critique of Anthropology 23(2):123–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X03023002001.

- Green, M., 2014. The Development State: Aid, Culture & Civil Society in Tanzania. Woodbridge, James Currey.

- Hickey, S., and S. King. 2016. “Understanding Social Accountability: Politics, Power and Building New Social Contracts.” The Journal of Development Studies 52 (8): 1225–1240. doihttps://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1134778.

- Hood, C. 2007. “What Happens When Transparency Meets Blame-avoidance?” Public Management Review 9 (2): 191–210. doihttps://doi.org/10.1080/14719030701340275.

- Hood, C. 2010. The Blame Game- Spin, Bureaucracy and Self-Preservation in Government. Princeton University Press. https://epdf.tips/the-blame-game-spin-bureaucracy-and-self-preservation-in-government.html

- Joshi, A. 2014. “Reading the Local Context: A Causal Chain Approach to Social Accountability.” IDS Bulletin 45 (5): 23–35. doihttps://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12101.

- Joshi, A. 2017. “Legal Empowerment and Social Accountability: Complementary Strategies toward Rights-based Development in Health?” World Development 99: 160–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.07.008.

- Lange, S. 2008. “The Depoliticisation of Development and the Democratisation of Politics in Tanzania: Parallel Structures as Obstacles to Delivering Services to the Poor.” Journal of Development Studies 44 (8): 1122–1144. doihttps://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802242396.

- Lee, T. W. 1999. Using Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Maghimbi, S. 2012. “The Quality of Education in Tanzania : An Exploration into Its Determinants.” Journal of Education, Humanities and Sciences (JEHS) 1 (1): 2012.

- Mansuri, G., and V. Rao. 2013. Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY, 3. http://jehs.duce.ac.tz/index.php/jehs/article/view/25/

- Mdee, A., A. Wostry, A. Coulson, and J. Maro. 2019. “A Pathway to Inclusive Sustainable Intensification in Agriculture? Assessing Evidence on the Application of Agroecology in Tanzania. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 43 (2): 201–227.

- Mdee, A., and E. Harrison. 2019. “Critical governance problems for farmer-led irrigation: Isomorphic mimicry and capability traps„. Water Alternatives 12 (1): 30–45.

- Mdee, A., and L. Thorley 2016a. “Good Governance, Local Government, Accountability and Ser Vice Delivery in Tanzania: Exploring the Context for Creating a Local Governance Performance Index.” ESRC Research Project. https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/WP2_Local-governance-and-accountability-in-Tz_Mzumbepaper_FINAL_311016.pdf

- Mdee, A., and L. Thorley. 2016b. Improving the Delivery of Public Services What Role Could a Local Governance Index Play? Economic & Social Research Council. https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/WP1_Measuring-local-governance_FINAL.pdf

- Mdee, A., and L. Thorley. 2016c. “Knowing Your Rights Is Something, but Not Enough: Exploring Collective Advocacy and Rights to Treatment and Services for People Living with HIV inTanzania.” Africanus-Journal of Development Studies 46 (2): 40–56. UNISA South Africa. doi:https://doi.org/10.25159/0304-615X/2071.

- Mdee, A., P. Tshomba, and A. Mushi. 2017. “Designing a Local Governance Performance Index (LGPI): A Problem-solving Approach in Tanzania.” Working Paper. London: Overseas Development Institute. https://dl.orangedox.com/EcHpUB

- Mercer, C. 2003. Performing partnership: civil society and the illusions of good governance in Tanzania. Political Geography 22 (7): 741–763.

- Muro, J. E., and G. S. Namusonge. 2015. “Governance Factors Affecting Community Participation In Public Development Projects In Meru District In Arusha In Tanzania.” International Journal Of Scientific & Technology Research 4 (6): 106–110. doihttps://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.060525.

- Olivier de Sardan, J. P. 2011. “The Eight Modes of Local Governance in West Africa.” IDS Bulletin 42 (2): 22–31. doihttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00208.x.

- Osaghae, E. E. 2006. “Colonialism and Civil Society in Africa: The Perspective of Ekeh’s Two Publics.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17 (3): 233–245. doihttps://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-006-9014-4.

- Purdeková, A. 2011. ““Even if I Am Not Here, There are so Many Eyes”: Surveillance and State Reach in Rwanda.” Journal of Modern African Studies 49 (3): 475–497. doihttps://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X11000292.

- Ran, R. 2017. “Understanding Blame Politics in China’s Decentralized System of Environmental Governance: Actors, Strategies and Context.” The China Quarterly 231: 634–661. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741017000911.

- Resodihardjo, S. L., B. J. Carroll, C. J. A. van Eijk, and S. Maris. 2016. “Why Traditional Responses To Blame Games Fail: The Importance Of Context, Rituals, And Sub-Blame Games In The Face Of Raves Gone Wrong.” Public Administration 94 (2): 350–363. doihttps://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12202.

- Tembo, F., and J. Chapman. 2014. “In Search of the Game Changers: Rethinking Social Accountability.” Discussion Paper. London. www.odi.org/twitter

- Tembo, F., and J. Chapman. 2017. “In Search of the Game Changers: Rethinking Social Accountability.” Railway Gazette International: 29–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/ja9831453.

- Tidemand, P. 2008. Local Level Service Delivery, Decentralisation and Governance. Tokyo: JICA.

- Tidemand, P., A. Sola, A. Maziku, T. Williamson, J. Tobias, and C. Long. 2015. Local Government Authority (LGA) Fiscal Inequities and the Challenges of ‘Disadvantaged’ LGAs in Tanzania. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Wild, L., D. Booth, C. Cummings, M. Foresti, and J. Wales. 2015. Adapting Development Improving Services to the Poor. London: Overseas Development Institute.