ABSTRACT

Creating conditions to empower local people is an important determinant of health, and crucial in addressing health inequity. Yet, experimentation with initiatives to support public participation at a local level is threatened by enduring global economic instability. A better understanding of how different participatory approaches might address the social determinants of health would support future prioritisation of actions and investment.We reviewed recent literature and theories on initiatives to increase peoples’ influence in local decision-making and on social determinants of health. Our synthesis found little detail about the form and function of initiatives, but diverse factors deemed influential in achieving outcomes. Studies highlighted that pressure on resources undermines individual and community capacities to participate, and requires organisational leaders to think/act differently.Suggested priorities for local governance are: supporting capabilities and relationships between organisations and communities; creating safe and equitable spaces for interaction and knowledge-sharing; and changing institutional culture.

Background

Health inequities stem from unequal social, material and political conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age; and are typically referred to as social determinants of health (World Health Organization Citation2008). Unequal conditions affect people’s access to rights, capabilities and resources, shaping experiences in childhood; opportunities to access play, recreation and learning; access to decent work, housing and services and thus lifelong health and wellbeing (Dahlgren and Whitehead Citation1991; Popay et al. Citation2008). There is growing evidence that lack of control over decisions and actions that shape our lives and health is an important determinant of poor health; thus creating conditions for people to exert influence and control is crucial in addressing health inequity (Marmot et al. Citation2020; World Health Organization Europe Citation2019). Recent evidence suggests that more than ever people want to have a greater say in shaping policy actions that affect their lives (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2020). For example, in England, the Community Life Survey 2018–2019 reported that 52% of adults wanted more involvement in local decision-making, with only 25% feeling able to influence decisions affecting their local area (Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport Citation2019). These concerns have been recognised by recent World Health Organization health and development policy; with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development outlining a global commitment to further inclusive and participatory decision-making at all levels from the global to the local (United Nations Citation2020).

At a local level across the globe, governments, communities, and other organisational partners are experimenting with different approaches to increase public participation and influence in decisions and action at regional, city and/or neighbourhood levels, in ways that could improve determinants of health (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2020; World Health Organization Europe Citation2012). In the UK the ‘Health in All Policies Approach’ for example emphasises the importance of engagement of partners across sectors and affected populations. Yet little is known about how different approaches work to support people’s influence in local decision-making and actions that affect their lives. Recent academic work has furthered conceptual understanding of potential pathways from influence and control in day-to-day living environments to health inequalities (Whitehead et al. Citation2016), and of the potentially differential effects of community engagement in public health interventions more generally (Brunton et al. Citation2017). However, there are considerable challenges in linking engagement to outcome, and we need to understand how approaches to increase public influence and control in local decision-making and action, and the ways influence is exerted, ultimately address social determinants of health, particularly where this is not the explicit aim of an initiative.

Following the financial crisis of 2007/2008 the reality of constrained resources (particularly in Europe) is highly significant to the economic context for participatory policy action (Stuckler et al. Citation2017). In the UK there have been deep cuts to local government budgets (Lowndes and McCaughie Citation2013). The anticipated social and economic crisis in Europe following the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to further constrain local resources and entrench health inequities (Bambra et al. Citation2020).

This systematic review aimed to synthesise evidence on approaches which aim to increase people’s influence and control over local-level decision-making and action, with a focus on how these may impact on social determinants of health. While other reviews have looked more broadly at involvement in local government or evaluated approaches which could be described as consultation rather than influence and control (see, for example, Schafer (Citation2019)) this review aimed to fill the gap in understanding how participatory initiatives might contribute to changes in social determinants of health. This review specifically examines the literature in regard to the potential effects of influence and control, wider determinants of health, and long-term health and health inequities.

Methods

A protocol was developed prior to starting the review (see https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO registration number CRD42019154748).

Eligibility criteria

Population – We included empirical studies on initiatives to increase public participation and influence within any European country as we were most interested in studies which would offer the greatest relevance for interventions in the UK.

Interventions – Our focus was on initiatives which gave individuals or groups increased opportunity to influence and exercise control over local-level decisions and actions, in ways that could potentially affect social determinants of health. Acknowledging Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (Arnstein Citation1969) and recent public health scholarship on collective control (Popay et al. Citation2021) we were interested in initiatives with elements that supported local people to ‘have an effect’ (exert power) on the actions and decision-making choices of others (Hay Citation1997). Literature relating to informing or providing information, public involvement during research studies, and public/community engagement where there was no apparent opportunity to influence decision-making or action was therefore excluded.

Outcomes – We included initiatives where enhanced influence and control in local decisions and actions might affect health, well-being or social determinants of health in a local population. We defined ‘local’ as being individual communities of place, identity or interest. We excluded public participation/influence in decision-making at a national/country level.

Study design – We included European studies of any empirical design (reporting quantitative or qualitative data) in order to examine work of most relevance to the UK. We supplemented the empirical literature with additional papers from any country where relevant frameworks or theories were outlined, as we anticipated they would provide additional explanatory value regarding mechanisms of effects. We did not set any exclusion criteria on the basis of quality.

Other criteria – We included papers published in peer-reviewed publications since 2008, as this covered the period following the global financial crash with significant impact on local government financing. We excluded books, theses, and professional magazine articles as these are not peer-reviewed. We included grey literature evaluations from the UK that we were able to identify via online searching, or which were cited in reference lists of included studies.

Information sources

We drew on expertise developed locally of using theoretical searching, and cluster methodologies to scope a disparate set of literature across different disciplines and databases (Booth and Carrol Citation2015). We searched the following databases:

MEDLINE

EMBASE

Cochrane Library

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature)

HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium)

Web of Science (Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index)

The information specialist on the team carried out several rounds of searching between May and September 2019 to initially test and refine the search strategy and subsequently to run the searches across a broader selection of social science databases. We used supplementary searching methods of reference list screening and citation searching, and used the Open Grey database and websites specific to the UK for grey literature. The full search strategy in an example database is available as additional online material (Additional file 1).

Study selection

Retrieved citations were downloaded to a reference management system (EndNote Version 9) for screening. Titles and abstracts of retrieved citations were screened by a lead reviewer, with a 10% sample checked by a second member of the team, and discrepancies resolved by consensus or a third reviewer if necessary. Potentially relevant citations were obtained for full paper scrutiny.

Data collection process and data items

For the empirical studies, we extracted data on the details of the initiative, type of participants, summary of results, description of influencing factors and context, and reported associations between elements using a form developed for the review. For studies reporting theories and frameworks we extracted: focus area of the study; name of theory where applicable; and summary of the theory/framework.

Quality appraisal and risk of bias

We used checklists from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Citation2018) relevant to each empirical study design, to consider the quality of identified literature where possible. Appraisal checklists were not applicable for predominantly descriptive or theoretical studies.

Methods of synthesis

We used tabulation and narrative synthesis to explore the literature identified, and meta-synthesis to compare where theories and frameworks informed empirical data. A summary diagram informed by the theories and frameworks identified and a theory of change approach (Savaya and Waysman Citation2005) was used to structure reporting of the evidence.

Results

Study selection

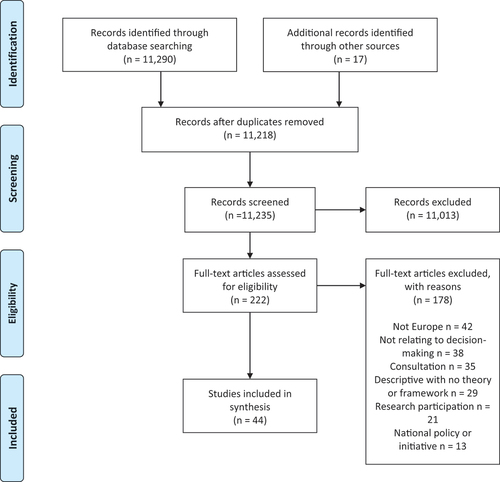

We screened 11,218 references found in electronic database searching, and examined 15 other potentially relevant reports. We looked in detail at 220 evidence sources and included 44 of these, representing 41 individual studies. outlines the evidence identification and selection process.

Study characteristics

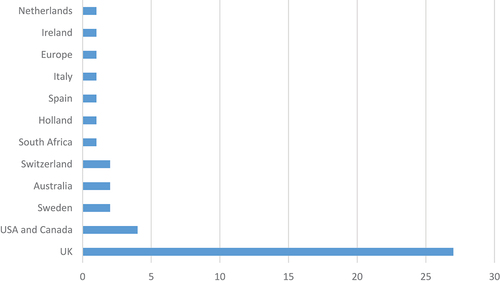

The included literature was dominated by UK research (), with the greatest proportion of qualitative or case study design (). We identified nine papers containing relevant theoretical models or frameworks (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Farmer et al. Citation2018; Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011; George et al. Citation2016; Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018; Healy Citation2009; Joerin et al. Citation2009; Lehoux, Daudelin, and Abelson Citation2012; Li et al. Citation2015). These models included the participation chain model (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015), social innovation theory (Farmer et al. Citation2018), a community capacity model (Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011), community capability model (George et al. Citation2016), decision process model (Joerin et al. Citation2009), and the biographical approach (Lehoux, Daudelin, and Abelson Citation2012).

Table 1. Included studies categorised by study design.

We identified eight other relevant reviews with some areas of overlap but differing focus to our work. These reviews focused on: community engagement initiatives (Attree et al. Citation2011); involvement strategies in environmental projects (Luyet et al. Citation2012); pathways from control to health inequalities (Whitehead et al. Citation2016); community capability (George et al. Citation2016); public and stakeholder engagement in the built environment (Leyden et al. Citation2017); community engagement (Brunton et al. Citation2017); the impact of joint decision-making on community well-being (Pennington et al. Citation2018); and opportunities to engage the public in local alcohol and other decision-making (McGrath et al. Citation2019). While these provided valuable findings regarding potential pathways to outcomes, studies had often been included which did not give opportunities for public influence and control. We therefore extracted only those findings answering our review questions.

Quality appraisal

Studies were appraised using checklists for each study design where appropriate (see Additional File 1). The quality of the included quantitative literature was limited, with few studies collecting data at more than one time point, predominantly descriptive reporting, and little use of statistical analysis. The qualitative studies rated better on appraisal, offering depth of insight into participant views and experiences.

Synthesis of results

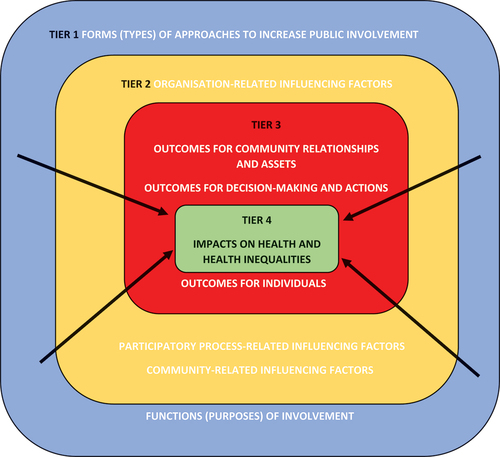

Given the complexity of the topic and findings, we developed a summary diagram () to provide a structure for reporting the evidence. We acknowledge that there are many ways of categorising the findings, and we drew on the models and theories we identified to produce our ‘best fit’ interpretation. We drew on a theory of change approach to consider: the form and function of public participation and influence (Tier one); factors within a local context influencing initiatives and their effects (Tier two); outcomes from involvement, including relationships, individuals, communities, and the decision-making/participatory process itself (Tier three); and finally potential impacts on social determinants of health and population health and well-being (Tier four). The following synthesis outlines evidence relating to each of these tiers, and where and how pathways of change may be traced between greater public participation and influence, and social determinants of health.

In the following synthesis, we have used the terminology of the source studies in our reporting. There was often little clarity in the language used by authors to describe concepts, for example, relating to communities, power and relationships. We return to this point in our discussion.

Tier one: forms and functions of public participation and influence

Initiatives to increase public participation and influence in local decision-making were reported in the areas of: planning and the built environment (five studies), health inequalities and social exclusion (one study), environmental management (three studies), urban regeneration (three studies), alcohol licencing (three studies), citizen welfare (one study), community empowerment (two studies reported in four papers), service reconfiguration and community capability building (one study), health services (three studies), road safety (one study), and community involvement/participation generally (three studies).

Included sources labelled approaches to public participation and influence in different ways: as ‘engagement activities’ with young people (one study); neighbourhood planning (four studies); planning aid (one study); a social inclusion partnership (one study); citizen sensor network (one study); participatory health impact/health needs assessment (three studies); asset-based approaches (three studies); financial investment (four studies reported in seven papers); alcohol licencing committee participation (two studies) and healthy cities networks (one study). Authors provided limited detail regarding exactly what activities formed part of the approach undertaken, and even less regarding how they were intended to support public participation and influence or what the intended function of people’s participation and influence was.

Recommended activities included: using graphics (Kimberlee Citation2008); virtual tools, social media, geographical information systems and decision support systems (Leyden et al. Citation2017); and publishing newsletters and establishing a communication plan (Lewis et al. Citation2019). Establishment of mechanisms for sharing information with the wider community was key (Heritage and Dooris Citation2009), with clear feedback and demonstration of commitment required (Parker and Murray Citation2012). Studies highlighted that a large number of meetings and public forums could be required to overcome barriers and mistrust (Linzalone et al. Citation2017), and communities need mechanisms to enable their involvement (Pennington et al. Citation2018; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016).

Theoretical papers provided more information about the intended functions of differing forms of activity with elements such as ‘”listening” and ‘responding’ being experienced as a vote of confidence in people’s personal competencies, and a signal that public views are valued and influential (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Li et al. Citation2015). The use of facilitators or community builders was reported as key to connecting community participants to other local resources (Farmer et al. Citation2018; Li et al. Citation2015) and creating transformative participatory spaces (protective niches) where trusting relationships between different stakeholders can grow. Thus promoting knowledge exchange and collective learning within decision-making, and limitation of professional dominance (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Farmer et al. Citation2018; Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011; Li et al. Citation2015).

Papers highlighted that approaches should involve a differing set of activities depending on the context (de Andrade Citation2016; Curry Citation2012; Markantoni et al. Citation2018; Garnett et al. Citation2017) and intended breadth, depth and reach (Lewis et al. Citation2019). While much public involvement tends to be ‘top down’ (Leyden et al. Citation2017; McGrath et al. Citation2019; Froding et al. Citation2013; Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018), literature emphasised the importance of starting from the communities’ agendas and not the organisations’ (de Andrade Citation2016; Curry Citation2012; Carlisle Citation2010), and avoiding aspirations of involvement turning into a cosmetic exercise (Leyden et al. Citation2017).

Sources highlighted that activities may need to change over time (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018) as aspirations grow, policies change (Attree et al. Citation2011), or enthusiasm wanes (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012). Studies emphasised the need for continuity of public involvement, and consideration of sustainability, organisational commitment and funding (Attree et al. Citation2011; de Andrade Citation2016; Froding et al. Citation2013; Deas and Doyle Citation2013; Durose and Lowndes Citation2010; Popay, Whitehead, and Carr-Hill et al. Citation2015). Sustainability should be grounded in a shared vision and expectations (Farmer et al. Citation2018).

Studies emphasised that involvement should take place early (Linzalone et al. Citation2017; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; Carlisle Citation2010; Fuertes et al. Citation2012), there should be a holistic community approach (Durose and Lowndes Citation2010), involvement of multiple agencies (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012), formal and organised involvement strategies (Markantoni et al. Citation2018), and an organisation policy in place to drive change (Deas and Doyle Citation2013). Strengthening of people’s perception of the possibilities (Froding, Elander, and Eriksson Citation2012), and effective governance to support and drive through initiatives is also required (Lewis et al. Citation2019).

Tier two: contextual factors influencing approaches and outcomes

The literature identified diverse factors within the operating context, which affect the characteristics, and effects of approaches and actions. We categorised these as factors relating to: organisations; participatory processes; and communities.

Organisations

Organisational factors predominantly related to local government as a key policy actor in local settings, but also extended to other ‘governing authorities’ (Garnett et al. Citation2017) such as local health boards.

Changes to the local government operating context could influence how much focus involvement was given internally (Deas and Doyle Citation2013). For example, change of individuals in key posts ‘completely changed the climate’ (Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018). The use of private companies to provide local services (such as refuse collection) led to local government distancing themselves from decision-making, and public opportunities to influence becoming ineffective (Chadderton et al. Citation2013).

Organisational culture determines the approach taken to public participation and the support provided, underpinning perceptions and organisational values regarding whether and how to involve the public (including cynicism about participation) and whether there is leadership (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016; Curry Citation2012; Durose and Lowndes Citation2010; Naylor and Wellings Citation2019). High-level support is needed for cultural transformation and changes in mindsets (Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008), together with training for staff in involvement approaches and new ways of working (de Andrade Citation2016). Studies noted how a lack of skills and/or knowledge in community engagement adversely effected an organisation’s ability to involve the public successfully (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016; Curry Citation2012; Durose and Lowndes Citation2010).

Culture and resource constraints can lead to insufficient costing of participation within tight budgets (Leyden et al. Citation2017; McGrath et al. Citation2019; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016). The requirement for efficiency in local government tends to be framed as inconsistent with public participation and influence, with ‘costs’ sometimes used as justification for not attempting approaches to increase involvement (Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; Chadderton et al. Citation2013; Brookfield Citation2017). Public participation is often not high up the budgetary agenda (Leyden et al. Citation2017; McGrath et al. Citation2019; de Andrade Citation2016), in a context of competition for resources (Carlisle Citation2010). Time and resource is also required from communities themselves; participants in one study described participation as ‘barely justifiable in regard to what was achieved’ (Curry Citation2012). Yet sustainability of funding is key if trust with communities is to be developed and organisations are to avoid ‘leaving communities when the money ran out’ (de Andrade Citation2016).

Personal, professional, and organisational attitudes shape the willingness to listen during public participation, with those who appreciate the value of public participation and knowledge most prepared to engage and/or consider new ways of working (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Healy Citation2009; Li et al. Citation2015; Curry Citation2012). Studies described ‘asymmetries of power’ between ‘expertise’ and public insights and understanding (Healy Citation2009), and variation in whether the public are acknowledged as legitimate participants (Lehoux, Daudelin, and Abelson Citation2012) and how problems are framed (Garnett et al. Citation2017).

Participatory processes

The key role of power inequalities was emphasised (Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018; Chadderton et al. Citation2013; Carton and Ache Citation2017; Durose et al. Citation2011) with reported dilemmas regarding how far initiatives should give communities decision-making powers. There might be a disparity between what local government perceive to be acceptable and sustainable, and resident expectations (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Nimegeer et al. Citation2016). Power at a local level can be limited by top down decision-making systems (Curry Citation2012), with national priorities and funding streams constraining choices (Carlisle Citation2010; Durose et al. Citation2011).

The literature highlighted that time was a key factor, both in allowing sufficient input from communities, building relationships (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Linzalone et al. Citation2017; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016; Curry Citation2012; Carlisle Citation2010; Durose and Lowndes Citation2010; Chadderton et al. Citation2013; Carton and Ache Citation2017), and developing shared trust (Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011). There can be potential for mismatches between community expectations of change, and time scales required to achieve it (Li et al. Citation2015; Luyet et al. Citation2012; Lewis et al. Citation2019; Heritage and Dooris Citation2009; Curry Citation2012; Garnett et al. Citation2017; Brookfield Citation2017).

Community-related

Involving a wide cross-section of any community in involvement initiatives was described as a sizeable challenge (Lewis et al. Citation2019; Heritage and Dooris Citation2009; Markantoni et al. Citation2018; Carlisle Citation2010; Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Deas and Doyle Citation2013; Brookfield Citation2017; Nimegeer et al. Citation2016; Lawless et al. Citation2009). Often small number of individuals participate, and there is a need to empower those who are typically excluded. Studies described community apathy, disenfranchisement, reluctance to engage, lack of awareness of opportunities, and participation of only those who were highly motivated (Leyden et al. Citation2017; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; de Andrade Citation2016; Froding et al. Citation2013; Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018). In one study, individuals driving activities were predominantly male homeowners in their 60s (Brookfield Citation2017).

Concepts of capacity and resilience were highlighted as influencing a communities’ ability to be involved (Brunton et al. Citation2017; Savaya and Waysman Citation2005; de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018); though with limited precision across papers in defining these terms. Participation might be most effective when community capacity is at a ‘tipping point’, or state of readiness, which could be harnessed by additional resource or stimulus (Brunton et al. Citation2017; Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018).

Multiple factors will influence whether community members participate, including: personal gain (wealth/health/skills), and community benefits ideas about altruism/responsible citizenship (Brunton et al. Citation2017). One study (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015) recommended a ‘mobilising’ approach via direct invitations and approaches to potential participants.

The concept of ‘communities’ was described as unclear and fluid, creating challenges to increasing involvement. Residents may not identify with a geographical area, demographic changes in the local area can adversely influence the cohesiveness of a community, and there can be shifting concepts of community boundaries (Lewis et al. Citation2019; Curry Citation2012; Carlisle Citation2010; Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Brookfield Citation2017; Orton et al. Citation2017; Reynolds Citation2018). Language and literacy affects participation (de Andrade Citation2016), and sub-community tensions can shape participatory processes, with differing perceptions of amenities, territorial pockets, and perceptions of inequalities in improvements (Lewis et al. Citation2019; Heritage and Dooris Citation2009; de Andrade Citation2016; Markantoni et al. Citation2018; Fitzgerald, Winterbottom, and Nicholls Citation2018; Deas and Doyle Citation2013; Durose et al. Citation2011). Papers raised questions about how ‘the public’ is defined (Garnett et al. Citation2017), and cautioned that any quest to involve ‘the ordinary citizen’ is challenging (Lehoux, Daudelin, and Abelson Citation2012).

Community ‘hubs’ and other social spaces are important facilitators of participation by developing and maintaining resident engagement and influence in local issues (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012). Yet weak economic conditions perpetuate limited investment by developers and providers of public services in such community assets and facilities (Deas and Doyle Citation2013). Limits to people’s personal resources (e.g., money, power and information) can also undermine individual or community capacity to participate (Whitehead et al. Citation2016; Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011).

Tier three: effects of involvement and influence

In common with many other public health interventions, pathways from involvement initiatives to effects are complex, multi-faceted and distal, and may be direct or indirect (Whitehead et al. Citation2016). Several frameworks identified offered varying typologies of outcomes (CitationWhitehead et al. Citation2016; Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011; Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018; McGrath et al. Citation2019; Pennington et al. Citation2018; Garnett et al. Citation2017; Brunton et al. Citation2017 #189, Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Lawless et al. Citation2009). We synthesised these into four main types of effects: on relationships or alliances across organisations and/or communities; on relationships and assets within communities; on the decision-making process and actions; and on individuals.

Effects on relationships or alliances across organisations and communities: Increased involvement in decision-making was associated with the formation of new relationships between local government and residents via new personal contacts and partnerships, and a shared sense of responsibility (Leyden et al. Citation2017; Parker and Murray Citation2012; Naylor and Wellings Citation2019; Reynolds Citation2018). The establishment of increased trust was central in these improved relationships (Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011; Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018; Pennington et al. Citation2018; Parker and Murray Citation2012; Linzalone et al. Citation2017; Lawless and Pearson Citation2012), together with joint commitment (Markantoni et al. Citation2018), and development of a shared vision (Orton et al. Citation2017).

Effects on relationships and assets within communities: Increased health literacy and health system literacy (Nimegeer et al. Citation2016), increased knowledge of community issues (Kimberlee Citation2008) and improved awareness of local issues and needs (Parker and Murray Citation2012) was reported. One study likened additional community knowledge to gaining ‘information-power’ (Carton and Ache Citation2017).

Other community outcomes following participation may be: improved social relationships, additional forms of mutual support, and networks of connections (Brunton et al. Citation2017); greater sense of community and community-mindedness, connectivity (social capital and cohesion) (Deas and Doyle Citation2013); group confidence and sense of entitlement to participate (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015); and the development of civic skills, knowledge and social and political awareness (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018). These outcomes were associated with increasing collective efficacy and power to take action (Brunton et al. Citation2017), and/or to advocate for change (Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011), and development of a shared vision for an area (Orton et al. Citation2017).

One study (Curry Citation2012) theorised that community participation in planning led to increased control and empowerment which then resulted in more community resilience. A further pathway to outcomes was suggested by a ‘strengthened community’ being associated with increased capacity to influence decision-making (Fuertes et al. Citation2012).

A note of caution, however, was provided by a finding that while there can be measurable increases in the intermediate outcome of ‘feeling part of the community’, this does not translate into statistically significant wider change in community outcomes (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Lawless et al. Citation2009). There were also reports of adverse outcomes, with increased involvement leading to conflicts within communities, and differing points of view regarding priorities for funding (Carlisle Citation2010; Orton et al. Citation2017).

Effects on decision-making and action: It is crucial to consider whether initiatives to increase involvement actually have a positive effect on decision-making and subsequent actions. Here, the evidence was mixed. Eight papers from seven studies suggested approaches to increase involvement had led to greater public influence on decisions made (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Parker and Murray Citation2012; Linzalone et al. Citation2017; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Fuertes et al. Citation2012; Carton and Ache Citation2017; Nimegeer et al. Citation2016; Lawless et al. Citation2009). Other papers reported that public involvement had influenced decision-making on spending priorities and policy choices regarding the local environment (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018; Whitehead et al. Citation2016; Freudenberg, Pastor, and Israel Citation2011).

We looked for evidence of the process whereby these effects might come about. Studies suggested that public participation was influential due to additional/alternative knowledge informing the decision-making process and decisions made (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Kimberlee Citation2008; Linzalone et al. Citation2017; Curry Citation2012; Fuertes et al. Citation2012; Chadderton et al. Citation2013; Nimegeer et al. Citation2016). Increased involvement might lead to community consensus regarding proposals (Linzalone et al. Citation2017), greater local government awareness of community needs (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018), and the plugging of knowledge ‘deficits’ (Farmer et al. Citation2018).

While reports of influence (perceived or actual) suggest positive effects, the literature also reported uncertainty regarding effects, or evidence of little effect, with organisational systems and short timescales precluding public participation (Chadderton et al. Citation2013; Iconic Consulting Citation2014). A lack of transparency in decision-making processes can make it difficult to tell whether or how public participation and influence shapes the decisions made (Kimberlee Citation2008). It was emphasised that if the effects are to be discerned, there is a need for involvement activities to be more clearly distinguished from consultation (McGrath et al. Citation2019).

Effects on individuals

Benefits for individuals in terms of well-being, self-confidence, self-esteem, physical, emotional and mental health (Attree et al. Citation2011; Pennington et al. Citation2018; Kimberlee Citation2008), as well as increased individual efficacy (McGrath et al. Citation2019) and individual empowerment were described (Attree et al. Citation2011; Pennington et al. Citation2018; Linzalone et al. Citation2017). Theoretical papers suggested increased sense of ability to make a difference, strengthened resources, motivation, confidence, perceived success and psychological empowerment (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018; Li et al. Citation2015).

However, the literature also highlighted potentially adverse effects for individuals in terms of exhaustion, frustration, stress, and fatigue from taking part (Attree et al. Citation2011; Pennington et al. Citation2018; Carlisle Citation2010). Engagement can become dispiriting and disempowering, resulting in scepticism, limited expectations of participation and reluctance to engage further (Brunton et al. Citation2017; Attree et al. Citation2011; McGrath et al. Citation2019; Parker and Murray Citation2012; Chadderton et al. Citation2013).

Tier four: impact on social determinants of health

We scrutinised the literature for evidence of a pathway from these outcomes to an impact on health inequalities or health determinants. A potential association between increased control and reduction in inequalities was suggested by an included review (Pennington et al. Citation2018). Another review hypothesised a potential association between community empowerment and personal psychological health and well being (Attree et al. Citation2011). A potential association between improved evidence-informed decision-making and population health improvement was also suggested (Chadderton et al. Citation2013). Other authors hypothesised that the development of civic skills, knowledge, and social and political awareness could potentially be linked to improved mental health impacts in the longer term (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018).

Studies evaluating involvement initiatives, however, found no relationship between participation/perceived influence in decision-making, and health impacts (Lawless and Pearson Citation2012; Lawless et al. Citation2009) or involvement in planning decision-making and inequalities (Brookfield Citation2017). Exclusion of marginalised groups may potentially reinforce inequalities (McGrath et al. Citation2019; Carpenter and Brownill Citation2008; Iconic Consulting Citation2014), and lack of representativeness may affect the validity of decisions made (Lewis et al. Citation2019; Nimegeer et al. Citation2016; Reynolds Citation2018).

Discussion

Our systematic review provides a range of insights into how initiatives to increase people’s influence and control in local decision-making and actions, might have an effect on social determinants of health and inequity.

Identifying and characterising initiatives that seek to enhance influence is challenging as they are inconsistently defined and characterised in the literature. Studies provided limited detail about specific activities were carried out, and even less information on how activities are intended to, or did function to enhance participation and influence. In this sense, much of the empirical evidence was ‘under-theorised’, showing limited engagement with existing intervention logics or theory. This type of ‘under-theorising’ has been noted by others in relation to the public health sciences more broadly (de Leeuw, Clavier, and Breton Citation2014; Hawe, Shiell, and Riley Citation2004). The ‘disconnect’ between some of the empirical and theoretical works could usefully be bridged to offer insights into different points of intervention within complex systems of local governance.

Greater theoretical engagement could support more rigorous evaluation of initiative effectiveness; promoting better understanding of the highly complex change pathways within local systems, and how and where participation and influence might impact. Currently, empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of approaches is dominated by descriptive accounts. If investment is to be made by local or national governments, other organisations, or indeed communities themselves, there is an urgent need to clarify the forms and functions of different activities in terms of participation and influence, and make more explicit the hypothesised pathways to improvements. In our reporting structure, we drew on a theory of change approach to explore pathways between forms and functions of participation, contextual factors, effects, and impact on social determinants. We suggest that such an approach is required in order to unpack complex pathways, and facilitate comparison of processes and outcomes in different contexts. Effects might have different pathways, for example, an initiative might function to support community capacities and strengthen relationships that might lead to more equitable distribution of public funds for services (Hagelskamp et al. Citation2018). In contrast, inviting people to participate, then listening and responding may function in a different way; by demonstrating to people that their competences/views are valued, and developing a sense that people can make a difference (de Freitas and Martin Citation2015; Li et al. Citation2015).

The evidence identified here echoes other scholarship in public health (Popay et al. Citation2021) which highlights that initiatives to enhance participation and influence often involve a range of different activities or forms of approach, which over time require considerable relational and political work on the part of those involved. We suggest that priorities for action within local systems of governance should be:

Treating involvement as a process to invest in over several years rather than a one-off activity related to a specific project or initiative.

Developing community capacities as essential for participation and influence.

Developing relationships and trust across and within organisations and communities to promote sharing of knowledge and other resources.

Creating safe, shared informal and formal spaces for more equitable forms of participation/interaction and knowledge-sharing.

Changing institutional culture and associated practices in ways that value public knowledge enabling participation and influence. This will likely require active learning and training to enable people to work in new ways.

Given the variety of factors in organisations, communities and individuals that can influence participatory initiatives, our findings suggest a need for context-specific support to enable change processes in all of these priorities for action. This enabling function could be provided for example by facilitators supporting the development of individual and/or community capacities. Wider research nevertheless warns that critical reflection is needed on the role and associated power dynamics of those who work at the interfaces in this way.

Many of the other factors affecting participation and influence in the review reflect deep-seated structural issues within local governance systems and systemic issues affecting the capacity of statutory organisations to work effectively with citizens. Particularly significant are asymmetries in power between professionals/expertise and public/lay knowledge (Picking et al. Citation2002; Popay et al. Citation1998). Despite an implicit focus on politics and power in the included evidence, these concepts were ‘under-theorised’. Other authors have similarly argued for more explicit engagement with concepts of politics and power within public health research, to provide additional insights into how, why and for whom policy initiatives work (de Leeuw, Clavier, and Breton Citation2014; Bambra, Fox, and Scott-Samuel Citation2005).

Constrained resources can impact the effectiveness of approaches to participation and influence within local governance systems, and this raises questions about the effectiveness of initiatives in the current economic context, particularly given the continuing social and economic impacts following the COVID-19 pandemic (Stuckler et al. Citation2017; Bambra et al. Citation2020). Recent reports highlight threats, particularly in more ‘ignored’ communities; not only due to the loss of community spaces, such as libraries and youth centres, but also because resource constraints can deeply affect people’s sense of collective identity and control (Young Citation2002; Gregory Citation2018; Marmot et al. Citation2020). There may, however, be an opportunity to harness the learning and confidence gained by those involved in collective efforts to respond to the unmet need in their communities (Macmillan Citation2020). Local government and other statutory organisations may also be able to build on relationships formed out of the emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Robinson Citation2020). The challenge now is to build on and sustain the relationships developed in a time of crisis, as well as for local governments that did not engage successfully to learn from those that did.

Changed institutional practices will require bold leaders to take risks and embrace thinking and acting differently, including valuing and legitimising lay capabilities and knowledge (Ham Citation2020). Yet it is unclear whether such risk-taking will take place, particularly if dominant institutional perceptions of public participation remain as a ‘cost’ to organisations. Our results highlight that being involved in initiatives can entail social and emotional costs to citizens, as participation can be stressful and frustrating. Given that the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been unequally felt by those already experiencing multiple disadvantages, mitigating these ‘costs of participating’ is now an even greater, but essential challenge to overcome if approaches are to impact on determinants of health and equity.

Limitations

Searching for literature on complex and poorly defined topics such as public involvement is known to be challenging, and there is the possibility that our searches did not identify all studies of relevance. We used supplementary methods of reference list and citation searching to help mitigate any limitations in our electronic database searching, but recognise that documents such as relevant grey literature may not have been included. It was challenging to distinguish between studies reporting public involvement or influence, from those relating to public consultation; and we may have inadvertently excluded studies where we were unable to discern the intention to involve, or where there was actual involvement of the public in decision-making.

Conclusions

This review of the literature on initiatives to increase public participation and influence in local decision-making linked to determinants of health, highlights a lack of transparency and theoretical engagement regarding how these initiatives are intended to act within local governance systems. Despite this, we have identified possible areas to prioritise for action to enhance participation and influence. If investment is to be made, particularly in times of resource-constraint, there is an urgent need to clarify both form and functions of different activities, and situate within complex and longer-term pathways to improvements in other determinants of health and inequity. While there is potential to build on the momentum of civic participation emerging from self-mobilising community emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic, initiatives may be at risk during times of limited resourcing: undermining individual/community capacities to participate, and requiring organisational leaders to think/act differently. The review suggests a need for support to enable change processes, particularly in response to deep-seated structural issues within local governance systems, and more explicit engagement with concepts of politics and power.

Availability of data and materials

All data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

SB led the review and wrote the initial version of the manuscript. AB contributed to the review processes and led on writing the background and discussion sections of the manuscript. CL and RM contributed to the review processes and contributed to editing of drafts of the manuscript. MC carried out the electronic database searching and contributed to the methods section of the manuscript.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As secondary research this study did not require ethical approval.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (296.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2022.2081551

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susan Baxter

Susan Baxter is a Senior Research Fellow in the School for Health and Related Research at the University of Sheffield. She carries out a broad portfolio of research relating to the delivery of health, care, and public health. She is particularly interested in the way that organisations and individuals work together, the inclusion of public voices in research, and using systematic review, logic model, and qualitative research to explore how the health of the public might be improved.

Amy Barnes

Amy Barnes is a Senior Lecturer in Public Health in the School for Health and Related Research at the University of Sheffield. Her research explores issues of equity, power, and participation in public health policy and community-based action to influence the social determinants of health equity. See Power, control, communities and health inequalities III: Participatory spaces - An English case. Powell K, Barnes A, et al. (2021) Health Promotion International, 36(5), 1264–1274.

Caroline Lee

Caroline Lee is a Senior Research Associate at Cambridge Public Health and Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. Her current research interests are place- and community asset-based approaches to public health and wellbeing and tackling health inequalities. Currently working on: supermarket community support activities and community wellbeing; evaluating a place-based, co-produced programme to support older people to remain happy at home for longer; Local Authority place-based approaches to addressing health and inequalities in times of austerity; and co-located community-based support to older adults’ mental health.

Rebecca Mead

Rebecca Mead is a Senior Research Associate at Lancaster University in the Division of Health Research and the Liverpool and Lancaster Collaboration for Public Health Research (LiLaC). Her research focuses on place-based approaches to influencing the social determinants of health equity. See Power, control, communities and health inequalities I: theories, concepts and analytical frameworks Popay, J., Whitehead, M., Ponsford, R., Egan, M., Mead, R. 31/10/2021 In: Health Promotion International. 36, 5, p. 1253–1263.

Mark Clowes

Mark Clowes is an information specialist in the School of Health and Related Research at the University of Sheffield. He has a research interest in emerging review methods and the use of artificial intelligence to assist the evidence synthesis process. He is a co-author of the third edition of the Sage textbook “Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review” (Booth et al., 2021).

References

- Arnstein, S.R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Attree, P., B. French, B. Milton, S. Povall, M. Whitehead, and J. Popay. 2011. “The Experience of Community Engagement for Individuals: A Rapid Review of Evidence.” Health & Social Care in the Community 19 (3): 250–260. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00976.x.

- Bambra, C., D. Fox, and A. Scott-Samuel. 2005. “Towards a Politics of Health.” Health Promotion International 20 (2): 187–193. doi:10.1093/heapro/dah608.

- Bambra, C., R. Riordan, J. Ford, and F. Matthews. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 214401.

- Booth, A.C., and C. Carrol. 2015. “Systematic Searching for Theory to Inform Systematic Review: Is It Feasible? is It Desirable.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 32 (3): 220–235. doi:10.1111/hir.12108.

- Brookfield, K. 2017. “Getting Involved in Plan Making: Participation in Neighbourhood Planning in England.” Environment and Planning C-Politics and Space 35 (3): 397–414. doi:10.1177/0263774X16664518.

- Brunton, G., J. Thomas, A. O’-Mara-Eves, F. Jamal, S. Oliver, and J. Kavanagh. 2017. “Narratives of Community Engagement: A Systematic Review-Derived Conceptual Framework for Public Health Interventions.” BMC Public Health 17 (1). doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4958-4.

- Carlisle, S. 2010. “Tackling Health Inequalities and Social Exclusion Through Partnership and Community Engagement? A Reality Check for Policy and Practice Aspirations from a Social Inclusion Partnership in Scotland.” Critical Public Health 20 (1): 117–127. doi:10.1080/09581590802277341.

- Carpenter, J., and S. Brownill. 2008. “Approaches to Democratic Involvement: Widening Community Engagement in the English Planning System.” Planning Theory and Practice 9 (2): 227–248. doi:10.1080/14649350802041589.

- Carton, L., and P. Ache. 2017. “Citizen-Sensor-Networks to Confront Government Decision-Makers: Two Lessons from the Netherlands.” Journal of Environmental Management 196: 234–251. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.02.044.

- Chadderton, C., E. Elliott, N. Hacking, M. Shepherd, and G. Williams. 2013. “Health Impact Assessment in the UK Planning System: The Possibilities and Limits of Community Engagement.” Health Promotion International 28 (4): 533–543. doi:10.1093/heapro/das031.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklists Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; 2018. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Curry, N. 2012. “Community Participation in Spatial Planning: Exploring Relationships Between Professional and Lay Stakeholders.” Local Government Studies 38 (3): 345–366. doi:10.1080/03003930.2011.642948.

- Dahlgren, G.W., and M. Whitehead. 1991. Policies and Strategies to Promote Social Equity in Health. Stockholm: Institute for Futures Studies.

- de Andrade, M. 2016. “Tackling Health Inequalities Through Asset-Based Approaches, Co-Production and Empowerment: Ticking Consultation Boxes or Meaningful Engagement with Diverse, Disadvantaged Communities?” Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 24 (2): 127–141. doi:10.1332/175982716X14650295704650.

- de Freitas, C., and G. Martin. 2015. “Inclusive Public Participation in Health: Policy, Practice and Theoretical Contributions to Promote the Involvement of Marginalised Groups in Healthcare.” Social Science & Medicine 135: 31–39. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.019.

- de Leeuw, E., C. Clavier, and E. Breton. 2014. “Health Policy – Why Research It and How: Health Political Science.” Health Research Policy and Systems 12 (1): 55. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-12-55.

- Deas, I., and J. Doyle. 2013. “Building Community Capacity Under ‘Austerity Urbanism’: Stimulating, Supporting and Maintaining Resident Engagement in Neighbourhood Regeneration in Manchester.” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal 6 (4): 365–380.

- Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport. 2019. Community Life Survey 2018-19. London: Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

- Durose, C., and V. Lowndes. 2010. “Neighbourhood Governance: Contested Rationales Within a Multi-Level Setting – A Study of Manchester.” Local Government Studies 36 (3): 341–359. doi:10.1080/03003931003730477.

- Durose, C., J. France, R. Lupton, and L. Richardson. 2011. Towards the ‘Big Society’: What Role for Neighbourhood Working?: Evidence from a Comparative European Study. London: Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Farmer, J., K. Carlisle, V. Dickson-Swift, S. Teasdale, A. Kenny, J. Taylor, F. Croker, et al. 2018. ”Applying Social Innovation Theory to Examine How Community Co-Designed Health Services Develop: Using a Case Study Approach and Mixed Methods.” BMC Health Services Research 18 (1). doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2852-0.

- Fitzgerald, N., J. Winterbottom, and J. Nicholls. 2018. “Democracy and Power in Alcohol Premises Licensing: A Qualitative Interview Study of the Scottish Public Health Objective.” Drug and Alcohol Review 37 (5): 607–615. doi:10.1111/dar.12819.

- Freudenberg, N., M. Pastor, and B. Israel. 2011. “Strengthening Community Capacity to Participate in Making Decisions to Reduce Disproportionate Environmental Exposures.” American Journal of Public Health 101 (Suppl 1): S123–S30. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300265.

- Froding, K., I. Elander, and C. Eriksson. 2012. “Neighbourhood Development and Public Health Initiatives: Who Participates?” Health Promotion International 27 (1): 102–116. doi:10.1093/heapro/dar024.

- Froding, K., J. Geidne, I. Elander, and C. Eriksson. 2013. “Towards Sustainable Structures for Neighbourhood Development? Healthy City Research in Four Swedish Municipalities 2003-2009.” Journal of Health Organization and Management 27 (2): 225–245. doi:10.1108/14777261311321798.

- Fuertes, C., M.I. Pasarin, C. Borrell, L. Artazcoz, E. Diez, and Group of Health in the N. 2012. ”Feasibility of a Community Action Model Oriented to Reduce Inequalities in Health”. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 107 (2–3): 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.001.

- Garnett, K., T. Cooper, P. Longhurst, S. Jude, and S. Tyrrel. 2017. “A Conceptual Framework for Negotiating Public Involvement in Municipal Waste Management Decision-Making in the UK.” Waste Management 66: 210–221. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2017.04.022.

- George, A.S., K. Scott, V. Mehra, and V. Sriram. 2016. “Synergies, Strengths and Challenges: Findings on Community Capability from a Systematic Health Systems Research Literature Review.” BMC Health Services Research 16 (Suppl 7): 623. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1860-1.

- Gregory, D. S. O. 2018. The Collapse and Revival of England’s Social Structure. London: Local Trust.

- Hagelskamp, C., D. Schleifer, C. Rinehart, and R. Silliman. 2018. “Participatory Budgeting: Could It Diminish Health Disparities in the United States?” Journal of Urban Health 95 (5): 766–771. doi:10.1007/s11524-018-0249-3.

- Ham, C. 2020. “Engaging People and Communities Will Help Avoid a Resurgence of Covid-19.” The BMJ Opinion.

- Hawe, P., A. Shiell, and T. Riley. 2004. “Complex Interventions: How “Out of Control” Can a Randomised Controlled Trial Be?.” BMJ Clinical Research Ed 328 (7455): 1561–1563. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561.

- Hay, C. 1997. “Divided by a Common Language: Political Theory and the Concept of Power.” Politics 17 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1111/1467-9256.00033.

- Healy, S. 2009. “Toward an Epistemology of Public Participation.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (4): 1644–1654. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.05.020.

- Heritage, Z., and M. Dooris. 2009. “Community Participation and Empowerment in Healthy Cities.” Health Promotion International 24 (Supplement 1): i45–i55. doi:10.1093/heapro/dap054.

- Iconic Consulting. 2014. Strengthening the Community Voice in Alcohol Licensing Decisions in Glasgow. London: Iconic Consulting.

- Joerin, F., G. Desthieux, S.B. Beuze, and A. Nembrini. 2009. “Participatory Diagnosis in Urban Planning: Proposal for a Learning Process Based on Geographical Information.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (6): 2002–2011. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.08.024.

- Kimberlee, R. 2008. “Streets Ahead on Safety: Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making to Address the European Road Injury ‘Epidemic’.” Health & Social Care in the Community 16 (3): 322–328. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00762.x.

- Lawless, P., M. Foden, I. Wilson, and C. Beatty. 2009. “Understanding Area-Based Regeneration: The New Deal for Communities Programme in England.” Urban Studies 47 (2): 257–275. doi:10.1177/0042098009348324.

- Lawless, P., and S. Pearson. 2012. “Outcomes from Community Engagement in Urban Regeneration: Evidence from England’s New Deal for Communities Programme.” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (4): 509–527. doi:10.1080/14649357.2012.728003.

- Lehoux, P., G. Daudelin, and J. Abelson. 2012. “The Unbearable Lightness of Citizens Within Public Deliberation Processes.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (12): 1843–1850. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.023.

- Lewis, S., C. Bambra, A. Barnes, M. Collins, M. Egan, E. Halliday, et al. 2019. ”Reframing “Participation” and “Inclusion” in Public Health Policy and Practice to Address Health Inequalities: Evidence from a Major Resident-Led Neighbourhood Improvement Initiative.” Health & Social Care in the Community 27 (1): 199–206.

- Leyden, K.M., A. Slevin, T. Grey, M. Hynes, F. Frisbaek, and R. Silke. 2017. “Public and Stakeholder Engagement and the Built Environment: A Review.” Current Environmental Health Reports 4 (3): 267–277. doi:10.1007/s40572-017-0159-7.

- Li, K.K., J. Abelson, M. Giacomini, and D. Contandriopoulos. 2015. “Conceptualizing the Use of Public Involvement in Health Policy Decision-Making.” Social Science & Medicine 138: 14–21. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.023.

- Linzalone, N., A. Coi, P. Lauriola, D. Luise, A. Pedone, and R. Romizi, D. Sallese, et al. 2017. ”Participatory Health Impact Assessment Used to Support Decision-Making in Waste Management Planning: A Replicable Experience from Italy”. Waste Management 59: 557–566. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.09.035.

- Lowndes, V., and K. McCaughie. 2013. “Weathering the Perfect Storm? Austerity and Institutional Resilience in Local Government.” Policy and Politics 41 (4): 533–549. doi:10.1332/030557312X655747.

- Luyet, V., R. Schlaepfer, M.B. Parlange, and A. Buttler. 2012. “A Framework to Implement Stakeholder Participation in Environmental Projects.” Journal of Environmental Management 111: 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.06.026.

- Macmillan, R. 2020. “Rapid Research COVID-19. Grassroots Action: The Role of Informal Community Activity in Responding to Crises.” In Briefing. Vol. 3. London: Local Trust.

- Markantoni, M., A. Steiner, J.E. Meador, and J. Farmer. 2018. “Do Community Empowerment and Enabling State Policies Work in Practice? Insights from a Community Development Intervention in Rural Scotland.” Geoforum 97: 142–154. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.10.022.

- Marmot, M., J. Allen, T. Boyce, P. Goldblatt, and J. Morrison. 2020. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. London: Institute of Health Equity.

- Marmot, M., J. Boyce, T. Goldblatt, and P. Morrison. 2020. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. London: The Health Foundation.

- McGrath, M., J. Reynolds, M. Smolar, S. Hare, M. Ogden, J. Popay, K. Lock, et al. 2019. ”Identifying Opportunities for Engaging the ‘Community’ in Local Alcohol Decision-Making: A Literature Review and Synthesis”. International Journal of Drug Policy 74: 193–204. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.09.020.

- Naylor, C., and D. Wellings. 2019. A Citizen-Led Approach to Health and Care. Lessons from the Wigan Deal. London: Kings Fund.

- Nimegeer, A., J. Farmer, S.A. Munoz, and M. Currie. 2016. “Community Participation for Rural Healthcare Design: Description and Critique of a Method.” Health & Social Care in the Community 24 (2): 175–183. doi:10.1111/hsc.12196.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2020. Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Orton, L., E. Halliday, M. Collins, M. Egan, S. Lewis, R. Ponsford, K. Powell, et al. 2017. ”Putting Context Centre Stage: Evidence from a Systems Evaluation of an Area Based Empowerment Initiative in England.” Critical Public Health 27 (4): 477–489. doi:10.1080/09581596.2016.1250868.

- Parker, G., and C. Murray. 2012. “Beyond Tokenism? Community-Led Planning and Rational Choices: Findings from Participants in Local Agenda-Setting at the Neighbourhood Scale in England.” The Town Planning Review 83 (1): 1–28. doi:10.3828/tpr.2012.1.

- Pennington, A., M.B. Watkins, A.M. Bangali, J. South, and R. Corcoran. 2018. A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Impacts of Joint Decision-Making on Community Wellbeing. London: What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

- Picking, C., J. Popay, K. Staley, N. Bruce, C. Jones, and N. Gowman. 2002. “Developing a Model to Enhance the Capacity of Statutory Organisations to Engage with Lay Communities.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 7 (1): 34–42. doi:10.1258/1355819021927656.

- Popay, J., G. Williams, C. Thomas, and T. Gatrell. 1998. “Theorising Inequalities in Health: The Place of Lay Knowledge.” Sociology of Health & Illness 20 (5): 619–644. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00122.

- Popay, J.E., S. Escorel, M. Hernández, H. Johnston, J. Mathieson, L. Rispel. Understanding and Tackling Social Exclusion: Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health from the Social Exclusion Knowledge Network. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- Popay, J., M. Whitehead, R. Carr-Hill, Dibben, C., Dixon, P., Halliday, E., Nazroo, J., Peart, E., Povall, S., Stafford, M., et al. 2015. The Impact on Health Inequalities of Approaches to Community Engagement in the New Deal for Communities Regeneration Initiative: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. Public Health Research 3 (12). doi:10.3310/phr03120.

- Popay, J., M. Whitehead, R. Ponsford, M. Egan, and R. Mead. 2021. “Power, Control, Communities and Health Inequalities I: Theories, Concepts and Analytical Frameworks.” Health Promotion International 36 (5): 1253–1263. doi:10.1093/heapro/daaa133.

- Reynolds, J. 2018. “Boundary Work: Understanding Enactments of ‘Community’ in an Area-Based, Empowerment Initiative.” Critical Public Health 28 (2): 201–212. doi:10.1080/09581596.2017.1371276.

- Reynolds, J.E. 2018. Identifying Mechanisms to Engage the Community in Local Alcohol Decision Making: Insights from the CELAD Study. London: School for Public Health Research.

- Robinson, D. 2020. The Moment We Noticed. London: Relationships Project.

- Savaya, R., and M. Waysman. 2005. “The Logic Model.” Administration in Social Work 29 (2): 85–103. doi:10.1300/J147v29n02_06.

- Schafer, J. 2019. “A Systematic Review of the Public Administration Literature to Identify How to Increase Public Engagement and Participation with Local Governance.” Journal of Public Affairs 19 (2). doi:10.1002/pa.1873.

- Stuckler, D., A. Reeves, R. Loopstra, M. Karanikolos, and M. McKee. 2017. “Austerity and Health: The Impact in the UK and Europe.” European Journal of Public Health 27 (suppl_4): 18–21. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckx167.

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals 2020. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

- Whitehead, M., A. Pennington, L. Orton, S. Nayak, M. Petticrew, and A. Sowden, M. White, et al. 2016. ”How Could Differences in ‘Control Over Destiny’ Lead to Socio-Economic Inequalities in Health? a Synthesis of Theories and Pathways in the Living Environment”. Health & Place 39: 51–61. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.02.002.

- World Health Organization. 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation. Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization Europe. 2012. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: The Urban Dimension and the Role of Local Government. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Europe.

- World Health Organization Europe. 2019. Healthy, Prosperous Lives for All: The European Health Equity Status Report. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Europe.

- Young I. 2002. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press