ABSTRACT

With the aim of investigating effective approaches to extensive reading (ER) implementation, this study examines a reading programme carried out in an EFL classroom in China. Data were collected from two interviews with the teacher participant, teacher’s reflective journal, student survey (n = 59), student focus group interview (n = 5) and various documents related to the reading programme. Findings of the study indicate that teacher scaffolding, embodied in the roles of motivator, strategy guide and monitor, is essential for students’ sustained pleasure reading. In light of this, scaffolded extensive reading (SER) is put forward to denote a student-centred and teacher-facilitated reading approach.

Introduction

Scaffolding in L2 reading

Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) sociocultural theory emphasises the importance of peer interaction and teacher scaffolding. The concept Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) indicates that scaffolding, or assistance from more competent others (peers or teacher), helps learners achieve their greatest potential (Alexander and Fox Citation2013; Wood, Bruner, and Ross Citation1976). Another important aspect of sociocultural theory is that learners’ contextual backgrounds, including sociocultural and historical dimensions, should be taken into consideration and utilised as contributing factors in language teaching (Unrau and Alvermann Citation2008). Under the influence of sociocultural theory, some models have been created to demonstrate the relationship between reader, text, teacher and context (Ruddell and Unrau Citation2013). Based on bottom-up and top-down models, interaction theory interprets reading as a process involving text-decoding and higher-level strategies (e.g. cognitive and metacognitive strategies), previous and personal knowledge in the interpretation of text (Grabe Citation1991). Another proposition of the theory is that the process of reading entails many subprocesses which function simultaneously rather than in a linear manner, be it a bottom-up or top-down process (Tracey and Morrow Citation2017). On the one hand, interaction theory explains the basic mechanism of reading activity; on the other hand, it legitimises teaching and training reading strategies of various kinds (Grabe Citation2009; Hall Citation2005/Citation2015; Nation Citation2008, Citation2015).

In line with the sociocultural theory, Ruddell and Unrau’s (Citation2013) Reader-Text-Teacher model emphasises the importance of the learner (reader), the scaffolding-provider (teacher), the reading material (text) and the learning environment (classroom community) to interpret reading as a complicated meaning-construction process. In this model, learners’ life experiences are highlighted as prior beliefs and knowledge consisting of two dimensions: affective conditions (including motivation to read, sociocultural values and beliefs) and cognitive conditions (including linguistic knowledge and text-processing strategies). In the meaning-construction process, the purpose of reading, the reader’s prior knowledge, the scaffolding from teacher and peers all function as contributory factors. The outcome of this process ranges from improved linguistic knowledge to comprehension of the text, and to the changes of motivation and beliefs of the reader.

Extensive reading and its ten principles

In the past 20 years or so, myriad studies have explored and tested the benefits of extensive reading (ER) on L2 acquisition and learners’ affective and motivational development. In terms of linguistic benefits, evidence in the following aspects has been collected: reading (e.g. Beglar and Hunt Citation2014; McLean and Rouault Citation2017), writing (e.g. Mermelstein Citation2015; Park Citation2016), listening (e.g. Chang and Millett Citation2014), vocabulary (e.g. Alsaif and Masrai Citation2019; Suk Citation2017), grammar (e.g. Aka Citation2019; Lee, Schallert, and Kim Citation2015) and general linguistic competence (e.g. Nakanishi Citation2015). Regarding affective benefits, evidence demonstrates that ER contributes to learners’ motivation and attitudes towards L2 learning (e.g. Suk Citation2018; Yan Citation2016). Notwithstanding all the listed and other benefits of ER, this pedagogical approach is not quite popular in L2 classrooms, especially in secondary classrooms for the main reason that ER is regarded by many teachers and students as time-consuming and inefficient in improving exam scores (Chen Citation2018; Huang Citation2015). In recent years, there seemed to be a shift in research from testing the efficacy of ER towards seeking effective approaches to ER implementation, for example, through integrating ER into L2 curricula (Nakanishi Citation2015). This being the case, a relatively limited number of empirical studies have probed into this issue, particularly pedagogical strategies that teachers can adopt in their practice.

In the Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics (Richards, Weber, and Platt Citation1992, 133), ER is defined as a reading activity ‘intended to develop good reading habits, to build up knowledge of vocabulary and structure, and to encourage a liking for reading’. This definition highlights the pedagogical purposes of ER and indicates a certain degree of teacher involvement and responsibilities in carrying out ER. By comparison, in the seminal book, Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom (Day and Bamford Citation1998, 5), ER denotes ‘real-world reading but for a pedagogical purpose’. It remains unclear, however, how the pedagogical purpose could be achieved if teachers mainly play the role of ‘members of a reading community’ (Day and Bamford Citation1998, 47). As a supplement to the imprecise definition, the two scholars established 10 principles of ER, which were subsequently updated by Day (Citation2002, 137–141) as follows:

The reading material is easy.

A variety of reading material on a wide range of topics is available.

Learners choose what they want to read.

Learners read as much as possible.

The purpose of reading is usually related to pleasure, information and general understanding.

Reading is its own reward.

Reading speed is usually faster rather than slower.

Reading is individual and silent.

Teachers orient and guide their students.

The teacher is a role model of a reader.

These 10 principles from different perspectives reveal the nature of ER, thus serving as a benchmark for carrying out and evaluating ER practice. Specifically, the first three principles concerning reading materials, which need to be easy, diversified and selected by students, are all oriented towards the enjoyment of reading. Principle 5 and Principle 6 more explicitly accentuate the pleasure orientation of ER. The last three principles, through clarifying students’ and teachers’ roles in ER, reinforce the central status of learners and devolve teachers’ authority and regulation to students. Whilst these 10 principles have played a predominant role in providing guidance for ER implementation in the past two decades, as Waring and McLean (Citation2015, 161) put it, there is no ‘universal form of ER based on the Ten Principles’. In different teaching contexts, various forms of ER practice present themselves, one of which is Sustained Silent Reading (SSR): students read individually without any interruption even from the teacher who in most cases read together with students (Grabe Citation2009). Conceivably, reading large amounts of self-selected materials with teachers’ distant supervision could bring about improvement in language acquisition. However, due to the lack of guidance from the teacher and the absence of interaction between peers, SSR is regarded by some scholars and teachers as time-demanding and low-efficient (McLean and Poulshock Citation2018).

ER in Chinese secondary schools

In the context of Chinese secondary schools (students aged from 12 to 18), despite the fact that a considerable amount of extracurricular reading is required of students as stated in the national curriculum (CME Citation2017), students’ actual reading cannot be rigorously tested in the National Matriculation Entrance Test (NMET). Therefore, the implementation of ER is not widely carried out even in metropolitan cities like Shanghai where English education is more advanced than other regions in China (Zhang Citation2018). This phenomenon can be explained by two main reasons: first, Chinese secondary education is highly exam-oriented, which means teachers’ and students’ attention is drawn to improving academic performance efficiently while ER is not regarded as highly conducive to the efficiency (Huang Citation2015). Second, middle school EFL teachers have little access to training and resources concerning ER (Sun Citation2021). Thus, even though teachers recognise the value of ER, they do not have adequate competence or confidence, and equally importantly, they do not have the legitimised class time for ER. In spite of these difficulties and restrictions, research into ER in Chinese secondary schools has been growing in the past few years. Evidence shows that ER implementation in this context bears certain similarities. The most conspicuous shared feature is that teachers play a pivotal role in running an effective ER programme (Zhang Citation2018), which in essence deviates from the principles of ER (Day and Bamford Citation1998).

Research questions

In order to investigate pedagogical approaches to effective ER implementation, this qualitative case study reports on an EFL reading programme carried out in a secondary school in Beijing. Specifically, this study aims to answer the following two questions:

How is ER implemented in a secondary EFL classroom?

How do students respond to the pedagogical activities in the reading programme?

Methods

Participants

The teacher participant (with the pseudonym Cai) had been teaching EFL for eight years and she concluded from her teaching experience that proficient English learners achieved excellence in the language mostly through reading rather than doing countless exercises. Cai herself loved reading which, in her opinion, could help her appreciate the beauty of language. Cai showed particular interest in books relating to professional development, for example, concept teaching and personalised learning. Meanwhile, Cai admitted that teaching ER somewhat changed her reading preference. When she started teaching young adult literature, she found the reading process interesting and relaxing, therefore beneficial for both teenagers and adults. During the data collection period, Cai was teaching two Junior One (aged 12) English experimental classes whose students were selected from many applicants and their English was of a higher level compared with average classes, approximately equivalent to B1 and B2 of CEFR levels.

Data collection

To achieve triangulation, data were collected through different sources (Flick Citation2017) including semi-structured interviews with the teacher and five students, teacher’s reflective journal, student questionnaire survey (n = 59) and various documents related to the reading programme. The teacher participant was interviewed twice, at the beginning and the end of data collection period (six months apart). The first interview focused on her perceptions of ER and previous implementation experiences; the second was centred on concrete measures she took in the reading programme under study. Five volunteer students were interviewed via focus group discussion. An online survey, comprising 11 questions (10 multiple-choice questions and 1 open-ended question), was conducted at the end of data collection period to explore students’ attitudes, perceptions, preferences, difficulties and expectations in relation to ER. Eight out of the 10 multiple-choice questions in the survey had one open-ended option which enabled students to provide extra information if applicable. Other sources of data include the teacher’s reflective journal entries (submitted to the researcher at the end of each month during the data collection period) and various documents such as students’ relevant assignments, teaching plans and reading materials related to the programme.

Data analysis

Data from multiple-choice questions of the survey were processed with Microsoft Excel and presented in the form of percentage in the Findings section. Qualitative data, including interview transcripts, reflective journal entries, answers to open-ended questions of the survey and textual documents, were analysed following the six steps of systematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006):

Step 1 – Getting familiar with data: Through performing the transcription by myself (with some assistance from a transcription software), I familiarised myself with the data. In this process, I took notes of any thoughts which might lead to potential themes in the analytic memo.

Step 2 – Generating initial codes: Complete coding approach was employed to generate initial codes (Gibbs Citation2007), that is, I marked anything interesting or conducive to answering research questions without following specific frameworks or guidelines.

Step 3 – Searching for emergent themes: Comparing and synthesising the initial codes, I identified emergent themes and noted them down on the analytic memo, such as recommend/select/provide materials, provide guidance (teach reading strategies), organise ER-related activities, exercise supervision, students’ reasons for ER, students’ feedback, students’ difficulties, and students’ expectations of teacher.

Step 4 – Reviewing themes: I checked the relationship between the emergent themes, combined similar or overlapping ones, and generated a thematic map. Meanwhile, disconfirming evidence was integrated: I looked for codes which were inconsistent with the themes, and incorporated them (if possible) into the thematic map.

Step 5 – Defining themes: I improved the emergent themes into final themes with precise wording, i.e. teacher’s perceptions of ER, students’ perceptions of ER, teacher roles in ER implementation and students’ responses to related activities.

Step 6 – Presenting themes with in-depth description: Key and full citations were extracted from the transcripts to illustrate each final theme and presented in the Findings section.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the ethical committee of the Institution and the research conformed to British Educational Research Association (BERA) ethical standards.

After obtaining the ethical approval, Participant Information Sheet and Informed Consent Form were sent to the teacher participant who helped forward relevant documents to student participants. If the student wanted to participate in the study, they gave the information sheet and the consent form to their parents/guardians. With their consent, the student was recruited to the study. It is important to stress that parents did not agree on behalf of their children; rather, the students themselves made the choice prior to parental agreement.

Findings

Cai’s perceptions and implementation of ER

In Cai’s opinion, when doing ER, ‘students select their own books according to their interests, without specific reading tasks or teachers’ instructions on language learning’. In addition, ‘extensive reading involves some strategy teaching but teachers make little intervention in student reading’ (Cai, Interview 1). Cai displayed a very positive attitude towards ER and its impact on language acquisition, although she admitted that time was needed to see its long-term effect: ‘ER is an input and it is a long process to see how useful it is, but eventually it helps students achieve language fluency and competence’ (Cai, Interview 1).

When asked what factors Cai took into consideration when selecting or recommending reading materials to students, Cai mentioned three aspects: the difficulty of the material, students’ reading interests and coverage of a wide range of genres. About providing materials of different genres, she gave some explanations:

In the College Entrance Examination, various topics are covered in the reading comprehension passages, especially science and technology, so we choose something like the National Geographic as one type of reading material. Some students only like fictions, and they want to read nothing but novels. I don’t think it’s enough. (Cai, Interview 1)

To give full play to students’ interests, Cai allowed students to select their own books for SSR in class and library reading. However, Cai came to the realisation that for Junior One students, selecting books on their own could be challenging:

From parents’ feedback I knew that most students had no experience of reading original English novels or other authentic materials in English before starting middle school, so I recommended some books. I didn’t say you must choose from these books, but later I found most of them selected books from the list I recommended. (Cai, Interview 2)

In addition to recommending books for students, Cai provided systematic guidance and monitoring at the initial stage of the reading programme. In her journal, Cai recorded the guidance she gave students regarding how to choose suitable books:

Interest: First read the introduction and others’ comments. Make sure you’re interested in the topic and content, and you are willing to read it.

Difficulty: Try reading three to five pages. Make sure you’re able to understand at least 80% to 85% of the content. On each page, there shouldn’t be more than five to six new words, and the unknown words do not affect your understanding of the general idea. (Cai, Journal 2)

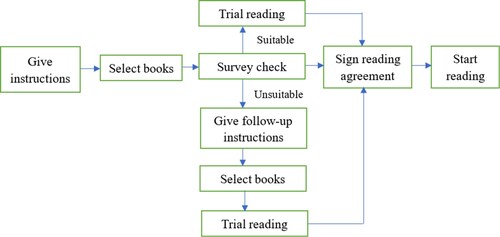

With detailed instructions on how to select reading materials, students had two weeks to choose their books. To check whether the books were suitable for each student, Cai conducted a survey and accordingly gave each student further guidance. For those who did not get suitable books judging by the results of the survey, Cai gave follow-up guidance until they found suitable ones. Following that, students had two-week trial reading. If they showed interest in the book and found the language was not too difficult or too easy, they would sign a ‘reading agreement’. This ceremonious activity, according to Cai, was aimed to make reading ‘a serious matter’ that students should not easily give up (Cai, Journal 3). When this whole process (see ) was completed, Cai started SSR in her class: ‘For 15-18 minutes in every English class, students do SSR. No tasks for the reading’ (Cai, Journal 1). For those who had not obtained suitable books yet or forgotten to bring the books to school, Cai prepared some books/magazines that she thought readable for most of the students (for example, National Geographic magazines) in the classroom and students could temporarily borrow these books or magazines for in-class reading.

Once a week, Cai took her students to the library where they did free reading for 40 min. Before the start of library reading, Cai asked a school librarian to give students a training session to help them more efficiently find suitable books. One picture that Cai took of her students reading in the library showed that students were sitting apart, each one enjoying sufficient space and immersed in individual reading (see ).

For the library reading, Cai also gave students detailed guidance and easy-to-follow instructions:

I taught them a series of reading strategies, for example, making predictions and inferences, and visualisation … when leaving the library, they need to complete a brief reading note – choose one strategy from the list I provide and tell me how they use the strategy. For example, if they choose ‘visualisation’, they could draw a picture to present an important chapter they’ve read. (Cai, Interview 2)

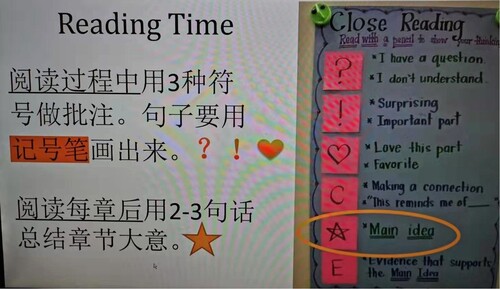

In her journal, Cai recorded some specific instructions she gave students regarding one reading strategy – making annotations, illustrated by a slide she used in class (see ):

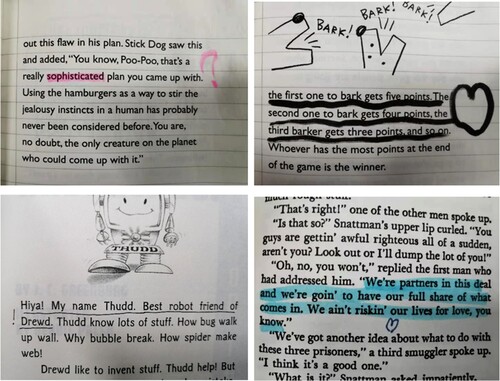

Rather than using words, Cai instructed students to utilise symbols to make annotations: question mark for question or confusion; exclamation mark for surprise or importance of the point; heart shape for liking. Cai collected some examples from students’ assignments which demonstrated how they applied the strategies to their reading (see ).

When asked whether incorporating SSR into EFL teaching affected finishing the syllabus, Cai answered:

I don’t think so. I had the fear before, and some of my colleagues had the same concern … but later on, I realized that using 15 minutes each day for SSR will be effective in the long run. Besides, I used the left 25 minutes of class time more efficiently. (Cai, Interview 2)

Students’ feedback and response to the reading programme

According to the data from questionnaires (n = 59), 49% of the students read English materials after class due to teacher’s suggestions and 31% did so because of teacher’s requirements. In the interview, one student said she spared some time for extracurricular reading in English almost every day, and most of the materials she read were from the teacher’s recommendation list. Another student said the main reason for her to read English books was to expand vocabulary, which was crucial for improving her performance in English exams. This reason echoed a result of the survey: 58% of the students read English materials to enhance their English studies. In comparison, fewer students (54%) read English for the fun of it. More than half of the students (61%) expected ‘recommendation on reading materials’ and 53% hoped for ‘encouragement’ from English teacher. Students’ need for encouragement corroborated another finding that 35% students lacked interest or motivation for English reading. Regarding the feedback on SSR in class, all the five interviewed students expressed positive attitudes; one gave such a comment:

Whether for knowledge accumulation or English improvement, the 15 minutes’ reading in class is the most efficient … I can get into the book … when I read after class, I may be distracted by many things, but in class, all of us are doing the same thing; there’s no distraction at all. (One student of Cai, Interview)

According to the data from the survey, 68% students considered ‘lack of time’ as a hindrance to reading in English. Students’ difficulty in time allocation for extracurricular reading seemed to explain why Cai arranged SSR in class rather than as an extracurricular activity. While expressing satisfaction with the arrangement of in-class reading, students also voiced their expectations of change or improvement: nearly half of the students anticipated ‘activities related to the reading’ (46%) and ‘provision of chances to discuss the reading with classmates’ (41%). It seems that the teacher’s intention of making ‘little intervention in student reading’ (Cai, Interview 1) collided a bit with students’ needs of collaborative reading activities. Related to this finding, to the last question of the survey (that is, making suggestions for the reading programme), one student gave the answer ‘customized reading tasks’ (written in English), and another three students provided answers of similar meanings but written in Chinese.

Discussion and conclusion

Teacher scaffolding in ER implementation

Judging by students’ responses to and expectations of ER-related teaching activities in the current study, it is arguable that teacher scaffolding plays an important role in ER implementation especially in secondary and lower L2 teaching contexts. This finding more or less contradicts the Ten Principles of ER (Day and Bamford Citation1998, 8) as analysed below. In Cai’s reading programme, 61% students expressed their need of teacher’s recommendation on reading materials, which reflected students’ difficulty in selecting suitable reading materials whether due to lack of time or resources. Cai’s systematic guidance on material selection to a certain degree reduced students’ difficulty in this aspect. Thus, it is arguable that emphasising ‘students select what they want to read’ is not enough, because some learners may not know how to choose their reading as a result of limited relevant knowledge and resources. Regarding what materials may suit learners, in conjunction with the principle that ‘reading materials are well within the linguistic competence of the students’, Cai gave central emphasis to engaging materials of a variety of genres. In other words, compelling content is no less important than appropriate language difficulty in material selection. Deviating from the principle that ‘the purposes of reading are usually related to pleasure, information, and general understanding’, 58% of Cai’s students read English materials for the purpose of improving English studies, more than those who read for the pleasure of it. In line with this finding, 80% students read English materials after class due to teacher’s suggestions or requirements. Conceivably, without teacher’s encouragement and monitoring, students’ reading time might have been occupied by other activities. Furthermore, not following the principle that ‘reading is individual … and outside class’, Cai’s students enjoyed the individual reading but in a collective manner, whether in the classroom or library. Collective reading was also embodied in the activities that Cai integrated into the programme, for example, teaching reading strategies and checking students’ application of the strategies. This seemed to diverge from the principle that ‘Reading is its own reward. There are few or no follow-up exercises after reading’, but 39% of the students regarded the strategy-related activities as helpful and important.

Summing up the roles that Cai played in the reading programme, we may conclude that the teacher was a motivator, strategy guide and monitor. That is to say, teachers’ encouragement, guidance and supervision are essential for students’ sustained pleasure reading, especially for beginning ER readers. In such L2 teaching contexts, the Ten Principles (Day and Bamford Citation1998) may not be sufficient to ensure effective ER implementation, and thus need to be supplemented by adequate teacher scaffolding.

Scaffolded extensive reading and its principles

To theorise what Cai practised in her reading programme, I tentatively use the term – scaffolded extensive reading (SER) with the following working definition: SER refers to the reading activity carried out for the main purpose of L2 learning through reading large amounts of engaging materials, facilitated by teacher scaffolding and guidance. With students’ increasing familiarity with the reading strategies and competence in selecting suitable reading materials, teachers’ assistance and monitoring play a decreasing role until not necessary. Drawing on Cai’s practice and students’ feedback, seven principles of SER could be abstracted as follows:

The reading material is engaging and accessible.

Teacher recommends/provides a variety of reading materials on a wide range of topics.

Teacher’s guidance on material selection is necessary.

Students read extensively for language development and for the pleasure of reading.

Teacher’s guidance on reading strategies is helpful.

Teacher’s monitoring and supervision is necessary especially in the initial stage.

Collaborative activities may enhance student reading motivation.

Aligned with the Compelling Comprehensible Input Hypothesis (Krashen, Lee, and Lao Citation2018), Principle 1 emphasises the dual foci of material selection: being engaging and accessible to engender reading pleasure and language acquisition. Principle 2 recognises teachers’ roles in material provision and recommendation, as is supported by the data from the survey: 61% students (the highest percentage for this question) expected teachers’ recommendation on reading materials for extracurricular English reading. Another important issue involved in material provision/recommendation, expressed by students in the survey and interview alike, is the variety of reading that caters to L2 readers of different competence and interest. Third, teacher’s systematic guidance on material selection, for example the procedures that Cai followed (see ), ensures each student finds their suitable reading, thus increases the effectiveness of the reading programme. Fourth, it is legitimate for L2 learners to read extensively for the purpose of developing language competence and/or academic performance, in addition to gaining pleasure from the reading. Relatedly, the survey showed that 58% students (the highest percentage for this question) read English materials for the purpose of improving English competence and exam performance in comparison with 54% for the fun of reading per se. Fifth, teaching reading strategies could be beneficial for students. In this study, 39% students regarded teacher’s instructions on reading strategies as necessary and helpful. Sixth, teacher’s supervision is crucial for students’ sustained reading. In Cai’s case, she observed students while they were reading in class or in the library, and offered assistance when they indicated need of help. For instance, Cai prepared some books to make sure everyone had something to read in class. Supervision also entails ‘encouragement’ which 53% of Cai’s students expected from the teacher. Seventh, collaborative activities may boost students’ reading motivation. Due to the nature of Cai’s reading programme – SSR, almost no collaborative activities were organised, which could explain why, respectively, 41% and 46% of Cai’s students expected chances to communicate with peers and such activities as performance and presentation related to the reading. Presumably, if such chances had been provided, lack of interest or motivation might not have influenced as many as 34% of the students’ English reading.

Compared with the Ten Principles of Day and Bamford (Citation1998), the principles of SER foreground teacher scaffolding, without which students especially beginning L2 extensive readers may easily give up reading due to various difficulties they are confronted with. Thus, the concept scaffolded extensive reading (SER) is put forward to complement the existing notion of ER and more importantly to help L2 teachers run an extensive reading programme in an effective and sustainable way. This concept has at least two implications: one, teachers are legitimised to get involved in students’ extensive reading rather than mainly acting as an example reader and keeping a distance without giving adequate support. Second, teachers need pedagogical knowledge to prepare themselves for providing necessary scaffolding regarding ER, for example, how to give guidance on material selection, reading strategies and maintain students’ motivation for pleasure reading.

As a qualitative case study, the present research has its limitations. First and foremost, findings from this single case cannot claim generalisability. Therefore, effective measures for ER implementation in this specific context should be taken with caution and prudence when regarded as potential approaches in other contexts. That being said, the importance of teacher scaffolding in ER implementation merits attention both in teaching practice and research field. Future research can explore further into L2 teacher education trajectories with respect to ER-related pedagogical knowledge and subject matter knowledge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aka, N. 2019. “Reading Performance of Japanese High School Learners Following a One-Year Extensive Reading Program.” Reading in a Foreign Language 31 (1): 1–18.

- Alexander, P.A., and E. Fox. 2013. “A Historical Perspective on Reading Research and Practice, Redux.” In Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, edited by D. E. Alvermann, N. Unrau, and R. B. Ruddell, 3–46. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Alsaif, A., and A. Masrai. 2019. “Extensive Reading and Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition: The Case of a Predominant Language Classroom Input.” International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 7 (2): 39–45. doi:10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.7n.2p.39.

- Beglar, D., and A. Hunt. 2014. “Pleasure Reading and Reading Rate Gains.” Reading in a Foreign Language 26 (1): 29–48.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Chang, A.C., and S. Millett. 2014. “The Effect of Extensive Listening on Developing L2 Listening Fluency: Some Hard Evidence.” ELT Journal 68 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1093/elt/cct052.

- Chen, I. 2018. “Incorporating Task-Based Learning in an Extensive Reading Programme.” ELT Journal 72 (4): 405–414. doi:10.1093/elt/ccy008.

- Chinese Ministry of Education (CME). 2017. 普通高中英语课程标准 (2017版) [National English Curriculum Standards for Regular High School (2017 Edition)]. Beijing: People’s Education Press.

- Day, R.R. 2002. “Top Ten Principles for Teaching Extensive Reading.” Reading in a Foreign Language 14 (2): 136.

- Day, R.R., and J. Bamford. 1998. Extensive Reading in the Second Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Flick, U. 2017. “Triangulation.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed., edited by N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln, 444–461. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Gibbs, G. 2007. Analysing Qualitative Data. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Grabe, W. 1991. “Current Developments in Second Language Reading Research.” TESOL Quarterly 25 (3): 375–406. doi:10.2307/3586977.

- Grabe, W. 2009. Reading in a Second Language: Moving from Theory to Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, G. 2005/2015. Literature in Language Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Huang, Y.C. 2015. “Why Don’t They Do it? A Study on the Implementation of Extensive Reading in Taiwan.” Cogent Education 2 (1): 1–13.

- Krashen, S., S. Lee, and C. Lao. 2018. Comprehensible and Compelling: The Causes and Effects of Free Voluntary Reading. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Lee, J., D.L. Schallert, and E. Kim. 2015. “Effects of Extensive Reading and Translation Activities on Grammar Knowledge and Attitudes for EFL Adolescents.” System 52: 38–50. doi:10.1016/j.system.2015.04.016.

- McLean, S., and J. Poulshock. 2018. “Increasing Reading Self-Efficacy and Reading Amount in EFL Learners with Word-Targets.” Reading in a Foreign Language 30 (1): 76–91.

- McLean, S., and G. Rouault. 2017. “The Effectiveness and Efficiency of Extensive Reading at Developing Reading Rates.” System 70: 92–106. doi:10.1016/j.system.2017.09.003.

- Mermelstein, A.D. 2015. “Improving EFL Learners’ Writing Through Enhanced Extensive Reading.” Reading in a Foreign Language 27 (2): 182–198.

- Nakanishi, T. 2015. “A Meta-Analysis of Extensive Reading Research.” TESOL Quarterly 49 (1): 6–37. doi:10.1002/tesq.157.

- Nation, I.S.P. 2008. Teaching ESL/EFL Reading and Writing. New York: Routledge.

- Nation, I.S.P. 2015. “Principles Guiding Vocabulary Learning Through Extensive Reading.” Reading in a Foreign Language 27 (1): 136–145.

- Park, J. 2016. “Integrating Reading and Writing Through Extensive Reading.” ELT Journal 70 (3): 287–295. doi:10.1093/elt/ccv049.

- Richards, J., H. Weber, and J. Platt. 1992. Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching. Harlow: Longman.

- Ruddell, R.B., and N.J. Unrau. 2013. “Reading as a Motivated Meaning-Construction Process: The Reader, the Text, and the Teacher.” In Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, 6th ed., edited by D.E. Alvermann, N.J. Unrau, and R.B. Ruddell, 1015–1068. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Suk, N. 2017. “The Effects of Extensive Reading on Reading Comprehension, Reading Rate, and Vocabulary Acquisition.” Reading Research Quarterly 52: 73–89. doi:10.1002/rrq.152.

- Suk, N. 2018. “L2 Students’ Perceptions of MReader for Extensive Reading.” Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning 21 (4): 163–180.

- Sun, X. 2021. “Literature in Secondary EFL Class: Case Studies of Four Experienced Teachers’ Reading Programmes in China.” The Language Learning Journal, 1–16. doi:10.1080/09571736.2021.1958905.

- Tracey, D. H., and L. M. Morrow. 2017. Lenses on Reading: An Introduction to Theories and Models. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Unrau, N.J., and D.E. Alvermann. 2008. “Literacies and Their Investigation Through Theories and Models.” In Tools for Matching Readers to Texts: Research-Based Practices, edited by H. A. E. Mesmer, 47–90. New York: Guilford Press.

- Vygotsky, L.S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

- Waring, R., and S. McLean. 2015. “Exploration of the Core and Variable Dimensions of Extensive Reading Research and Pedagogy.” Reading in a Foreign Language 27 (1): 160–167.

- Wood, D., J.S. Bruner, and G. Ross. 1976. “The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 17 (2): 89–100. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x.

- Yan, Q. 2016. “An Experimental Research on Original English Literary Works as Supplementary Materials for Extensive Reading Teaching in Senior High School.” Master’s diss., Hangzhou Normal University.

- Zhang, R. 2018. “The Study of Extensive Reading Class in High School: Using Young Adult Fictions as Reading Materials.” Master’s diss., Shanghai Normal University.