ABSTRACT

Forest School in England is the practice of young children playing outside, rooted in the outdoor kindergartens of Scandinavia and more especially Denmark. Using observation and semi-structured interviews with children and adults in two settings, this case study approach allowed an in-depth look at where, how and what children played in a Forest School in England compared with a Forest Kindergarten in Denmark. This study found that even though each case had contextual differences, with different conceptualisations of pedagogy and play, children were active in the process of their play. Choosing to play in familiar places, which resources they needed, on their own or with peers, but away from adults, a common theme to the play was play stories or narratives. Bounded by the two cases, and explored through play pedagogy, this study offers practitioners and pedagogues a unique insight into how children experience and operate in two similar yet different forest environments.

Introduction

Established by lecturers from Bridgwater College, Somerset, in 1993, Forest School in the UK is an alternative approach to playing outside for young children. After a trip to Denmark a group of lecturers adapted what they had seen and experienced in the college nursery, coining the term Forest School (Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012). Since then, its popularity as a way of working with young children has grown. The far-reaching positive effects on children’s all-round development (Murray and O’Brien Citation2005; O’Brien and Murray Citation2006) have resulted in many interpretations and adaptations of the initial approach alongside its popularity with young children.

Applying a qualitative case study approach, this research has explored the similarities and differences between children’s outside play in Forest School in England and Denmark. Using observation of children’s play, it was possible to identify children in both cases making comparable decisions regarding their play, where they played, the games, the resources used, and who they played with. Semi-structured interviews with children, pedagogues and practitioners were used to confirm these findings. By conceptualising Forest School and Forest Kindergarten through the lens of play, this study informs pedagogues and practitioners about children’s play in both contexts, identifying the benefits of using a play pedagogy in Forest School and Forest Kindergarten which can assist in future decision-making.

Forest Kindergarten

In Denmark, where children do not start formal schooling until they turn 6 (OECD Citation2014), there is an established tradition of using the outdoors with young children. Originally based on Froebel’s vision of kindergarten or a children’s garden, Danish early years provision combines education and care. An emphasis on social and emotional development embraces nature, providing opportunities to play and learn outdoors (Garrick Citation2009). There are many outside kindergartens that take their name and inspiration from their location or tradition. Examples include vandrebornehave or wandering kindergartens, where children roam free in the woods gathering at a cabin or base camp (Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012). Whereas at flutterbornehave children travel by bus into the countryside to benefit from spending time close to nature, where there is more available space and fresh air (Gulløv Citation2003).

Using social pedagogy and ‘appropriate pedagogical approaches’ (MSA Citation2014, 1) that centre on child-initiated or free play (Gulløv Citation2003), pedagogues have a clear philosophical and theoretical understanding that underpins their practice. In 1998 the Social Service Act introduced the concept of ‘learning’ for children under 7. More recently the Day Care Act (MSA Citation2004, Citation2014) set out six areas of learning: personal development; social development; language; body and movement; nature and natural phenomenon and cultural expression, which are similar to the six areas in the Early Years Framework Strategy (DfE Citation2017) in England.

Revised in 2018 and implemented in 2020 the pedagogical curriculum has recently been strengthened. Retaining the six curriculum themes, the legislation now has pedagogical objectives that more securely link the learning environment with children’s learning (MCE Citation2020, 16). Play should be child-initiated, children are ‘active co-creators’ of their own learning and have ‘time and space’ to be children (MCE Citation2020, 16). Nature and the natural environment motivate and inspire children to learn (Fjortoft Citation2004). With no formal assessments the curriculum retains an emphasis on pedagogy and remains a ‘soft’ approach to early childhood provision, particularly as the Danish government favours a persuasive stance rather than direct control (Wall, Litjens, and Taguma Citation2015).

Williams-Siegfredson (Citation2012) puts forward the pedagogical principles of Forest Kindergarten. Using a holistic approach, Forest Kindergarten is a learner-centred approach that views children as unique, competent active and interactive learners who learn best through first-hand experiences, so they learn how to be autonomous, independent and responsible (Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012). A key tenet is that children are allowed space and time to experiment and develop their own ideas and interests, with a high priority given to social interactions especially those with peers (Kristjansson Citation2006). Social relationships and play with peers are regarded as developmentally better than instruction from adults (Kristjansson Citation2006). This includes children making their own choices and self-management (Gulløv Citation2003) that is ‘free from excessive control and supervision’ (Wagner and Einarsdottir Citation2006, 292). Brostrom et al. (Citation2012) discovered that when children are allowed to play for extended periods of time they are more likely to be absorbed in their play, return to it to complete it and build on it, reliving their experiences and sharing their ideas and experiences.

Forest School

In England, education pioneers such as Macmillan were also influenced by Froebelian ideas. However, over time the use of outside play has lessened especially as children start formal schooling before they reach 5. The gradual regulation of practice since 1996 with the Desirable Learning Outcomes (SCAA Citation1996) that set out six areas of learning, alongside the introduction of baseline assessment in 1998 (gov.uk), then the establishment of the EFYS in 2008 has reduced practitioner autonomy (Garrick Citation2009). By the 1990s the idea of Forest School, as an

inspirational process that offers children, young people and adults, regular opportunities to achieve and develop confidence and self-esteem through hands-on experiences in a woodland environment (Forest School Association, FSA. Citation2019),

As a social movement (Cree and McCree Citation2012, 32), little was known about process and practice in Forest School (Swarbrick, Eastwood and Tutton Citation2004), until early studies by Massey (Citation2002) and Eastwood and Mitchell (Citation2003) revealed that learning was play-based, child-initiated and child-led. Forest School encourages children to learn and develop at their own pace (Murray and O’Brien Citation2005; O’Brien and Murray Citation2006), explore the environment through their senses, to be creative and independent (Wellings Citation2012). By establishing compatibility with the National Curriculum and the Early Years curriculum at the time, reports by Murray and O’Brien (Citation2005) and O’Brien and Murray (Citation2006) on the benefits of Forest School, facilitated its growth. Knight’s book on Forest School published in 2009, popularised the approach with practitioners. However, the Department for Education (DfE), has never officially approved its use (McCree and Cree Citation2012, 222). Consequently, there remains a gap between fully articulated pedagogy, theoretical underpinning and practice.

Alongside its growth in popularity, increased research started to identify differences in practice. Waite, Davis, and Brown (Citation2006) revealed adult imposed boundaries, not evident in early studies by Massey (Citation2002) and Eastwood and Mitchell (Citation2003). A high proportion of practitioner-led activities, with free play only occurring ‘in-between’ more formal activities, showed a potential shift in emphasis away from child-initiated play (Waite, Davis, and Brown Citation2006, 11). Variations may be attributed to early ‘grass roots’ practices (Cree and McCree Citation2012, 222) that spread through word of mouth rather than through ‘collectively defined principles’ (223) that articulate process, pedagogy or theoretical underpinning (Swarbrick, Eastwood and Tutton Citation2004).

Although using the outside is a recognised way of working with young children, and acknowledged in the EYFS, not all outside play is Forest School. Some examples of practices calling themselves Forest School may not be ‘learner-centred, play-based, long term and within a wooden area’ (McCree and Cree Citation2012, 223). Maynard’s (Citation2007b) initial exploration and more recently Mackinder’s (Citation2017) study both identified a difference in attitude between qualified early years’ practitioners and trained Forest School leaders, which may have contributed to the over-management seen by Waite, Davis, and Brown (Citation2006). Whilst the tighter structure imposed alongside the ‘directive and protective style’ observed in practitioners may be due to pressure from curriculum, assessment requirements and target setting imposed around this time (Maynard Citation2007a, 385).

Supported by research and founded on core beliefs, the FSA has established six main features that differentiate Forest School from other forms of outside learning (FSA Citation2019). Firstly, Forest School is a long-term process that happens in a wooded environment. Trees and woods are used to help to foster a relationship with nature that is based on personal experience. This can involve some managed exposure to risks such as fires and using tools, although the risk is viewed as a part of life and necessary to develop resilient, healthy and creative individuals. Opportunities build on an individual’s innate motivation and interests. Learning is intended to be holistic as it develops physical, social, cognitive, linguistic, emotional and spiritual aspects of the learner. A learner-centred pedagogical approach is used to respond to the needs of the learners with play and choice as the central feature. The adult leading Forest School should be trained and qualified practitioners. Approaches that involve observation and scaffolding help tailor experiences for participating individuals (FSA Citation2019). However, how the main principles are interpreted can vary in practice, depending on a range of circumstances specific to each case (McCree Citation2019). Therefore, more exploration and theorising are required to further understand the pedagogy of Forest School, starting with how children experience Forest School through play.

Play

In Western Europe play remains the ‘bedrock of early learning’ (BERA Citation2003, 14) and is a ‘leading factor in child development’ (Vygotsky Citation1978, 101). However, play is a complex concept with many characteristics that involve different activities, making it difficult to categorise and define (Else Citation2009). For example, Hughes (Citation2012) claims there are at least 12 different kinds, including social, imaginative, heuristic, and exploratory play. An understanding of what play is, children’s ability to play, and learning how to play is contextually and culturally situated and can be affected by many factors including family, culture and personal variations (Wood Citation2013).

Play and the study of play need to be positioned within a complex wider social, cultural-historical situation that influence how, what, when and where children play. Consequently, play can be considered from a range of viewpoints depending on the philosophical perspective, theoretical underpinning and pedagogical positioning of the individual involved (Wood Citation2013). In addition, different lenses applied by researchers, according to their view of play and the aspect of play being explored, can result in different conceptualisations (Wood Citation2009). With no universal definition of play (Reed and Brown Citation2000), there are many terms, often used interchangeably to refer to play, such as child-initiated play, free-play and play-based learning. To understand play it is useful to identify the main characteristics of play.

Characteristics of play

As an important feature of childhood, play is how children explore, develop understanding and make meaning from their experiences (Vygotsky Citation1978). Whilst it is useful to refer to some characteristics of play, not everything that children do is play or playful, as children can move in and out of play (Wood Citation2013). Children develop their ability to play at different rates, and Parten’s (Citation1932) stages of social play explain the development from solitary play to parallel play before participating in group and then co-operative play typical at approximately five years old. Agreement over play is important to develop a shared story that goes with the play (Bruce Citation1991). It is also important that children can reflect without feeling pressure from others (Bruce Citation1991; Vygotsky Citation1978).

A defining characteristic of play is that it should be fun and enjoyable (Meckley Citation2002) with a positive effect on the players (Moyles Citation2010). Part of the enjoyment comes from a play that is personally and intrinsically motivated (Pellegrini Citation1991; Saracho Citation1991). It is important that children feel physically, emotionally and psychologically safe enough to be able to develop coping strategies such as friendship, co-operation, confidence and self-efficacy, when problems and challenges do occur (Sutton-Smith Citation2001). Challenges should be seen as a chance for personal growth and development where children learn about others themselves and their own limits.

Play should be child invented (Meckley Citation2002) with very ‘little direct intervention’ from adults, so children can exhibit choice, control and imagination (Wood Citation2010, 20). Play that is child-initiated is driven by the children’s interests, and although spontaneous and open-ended it has meaning for them and involves them deeply, compared with play that is imposed by adults (Pellegrini Citation1991; Saracho Citation1991). By being able to make decisions about the direction and process of the play (Bruce Citation1991; Moyles Citation2010) the players become deeply involved (Wood Citation2009), which creates a sense of ownership (Bruce Citation1991; Moyles Citation2010). When children are involved deeply in play reality can be discarded so creativity and imagination can take over and learning takes place (Moyles Citation2010). Alternatively play that is ‘planned and purposeful’ (DfES Citation2017 , 11) can be outcome driven or have adult-imposed goals (Moyles Citation2010) that conflate play with work, often resulting in educational play (Wood Citation2013).

Play should be child-chosen so that children can develop ideas about what they want to play, where and who with, as children learn the most from the play that belongs to them. It is important that children can experiment and invent play that is ‘new to them’ (Wood Citation2013, 6–7). Open-ended resources contribute to the quality of play (Bruce Citation1991). To develop cognitively, socially and emotionally pretend play should allow children to draw on their ‘working theories’ and ‘funds of knowledge’ to explore relationships and rules pertaining to their own cultural and social experiences (Wood Citation2013, 6–7). When playing children use language, sign, symbol and gesture to communicate, focusing on doing, or the active process of playing rather than on an educational outcome (Vygotsky Citation1978). They should be able to play on their own terms, self-managing without adult interference. It is when children are in the flow of their play, with time and space that they can explore ideas and develop creativity (Bruce Citation1991).

Location and environment

Whilst there is consensus that Forest School and Forest Kindergarten should take place in or near a wood or forest (McCree and Cree Citation2012; Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012), there is a limited explanation concerning the physical environment or its features. Knight (Citation2012, 15) refers to the location as being a ‘special’ place where specific Forest School rules apply. Different locations contain individual features and different places that afford different ways to play, and no two are the same, making it tricky to compare like for like (Davis and Waite Citation2005; Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012).

The environment is an important resource as it provides everything children need, which motivates play, creates experiences and in turn results in learning (Knight Citation2013). Waite, Davis, and Brown (Citation2006) similar to Gulløv (Citation2003) posit that the natural environment should be both the context and focus of play, so that children play in, with and through the natural environment. As the outside environment is a dynamic, living space (Knight Citation2013), it evolves according to the needs of the users as they interact with and in it (Tovey Citation2010). Rather than being regulated by adults imposing a structure on it, adults involved in Forest play translate their pedagogy into practice as they construct learning environments in natural outdoor locations (Williams-Siegfredson Citation2012).

Different kinds of places and spaces and the play they afford, invite children to make their own connections and attachments (Tovey Citation2010) and a range of opportunities to interpret and use places in creative ways, such as trees as dens or for climbing. Intimate spaces allow for privacy with gaps for the children to see out yet remain concealed from view, so children frequently create their own special or secret places away from adults that are ‘calm, ordered and reassuringly secure’ (Tovey Citation2010, 75). Children need opportunities to explore the natural environment at their own pace (Murray and O’Brien Citation2005; O’Brien and Murray Citation2006), making Forest School a learner-centred pedagogical approach (Wellings Citation2012) ignited by children’s innate motivation and curiosity (Jarvis, Brock, and Brown Citation2014; Vygotsky Citation1978).

Summary

Rooted in Frobel, the idea of young children playing outside is not unique to either England or Denmark. Over time outside play in each context followed its own path until the 1990s when Danish early years practice inspired what we now know in England as Forest School. Even though in Denmark Forest Kindergarten is an accepted way for young children playing outside with a well-established pedagogy because practice reflects the unique environment where it takes place alongside the actions and needs of those involved there is no one way to do this. Conversely, in England Forest School is less embedded in tradition, and pedagogy is more elusive also resulting in many variations. For many reasons play is complex, as it is situated culturally in a place and Identifying play pedagogy and the characteristics of play are central to comparing young children's play behaviours in English Forest School and Danish Forest KIndergarten.

Methodology

Context of the study

The research reported here was carried out in two cases. The first was with a Forest School group in a nursery in England and the second was a Forest Kindergarten class in Denmark. In total this study involved six children, three in each case, aged between three and four years old.

To achieve a better understanding of children’s play preferences in each case, data were collected through photo tours, elicitation interviews and observation to confirm the reliability and credibility of findings (Black 1999). In consultation with the lead adult in each case, three children were selected and invited to participate. With consent the children participated by their play being observed and then interviewed. Lastly, to understand the social reality of the case (Stake Citation1995), the six children were each observed playing. Specifically, where they played, what and who they played with, and the type of play they engaged in including how they played.

Ethical considerations

British Educational Research Association (BERA Citation2018) and the Danish Research Code of Conduct (MHES Citation2014) ethical guidelines were used and adhered to. Before beginning the research process informed consent was obtained from the parents of the children involved. To further ensure the children’s privacy they were only observed with consent and on-going assent. When children were involved in data collection, they were regularly made aware through conversation and the use of smiley face charts that they did not have to take part and could withdraw at any time (Cutter-Mackenzie, Edwards, and Widdop-Quinton Citation2013; Docket, Perry, and Kearney Citation2013). To ensure anonymity the names of all the participants were changed (Flick Citation2014). All data was stored, encrypted and password protected.

Methods

In each case, interviews and observations were used to collect data in each case with all participants. To ensure data were collected comparably in each case data were collected over five sessions, adhering to a collection schedule.

Observation

One of the best ways to gain valuable insight into a case is to observe the actions, and emotions of a situation to identify the values, motivation and prejudices (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2011) or the social reality (Stake Citation1995). Used in previous Forest School research by Davis and Waite (Citation2005), Maynard (Citation2007a) and Mackinder (Citation2017), observation has been used to reveal insight into events and social interactions in a natural setting.

Separate observation of the three children in each case took place over the week so the children were familiar with the researcher and some rapport had developed (Denscombe Citation2010). Given that the participants were young children (three and four years) and may become aware they were being observed and change their behaviour (Yin Citation1994), it was considered preferable for the researcher to be a participant rather than non-participant (Merriam Citation1988) or a covert observer (Douglas Citation1976). Each child was observed playing in the playhouse, for approximately 20 min each, although the play moved as it evolved and the children interacted with peers. Extensive written notes recorded the time and place of each observation and includes detail on where the children played, the kind of play seen, what they played with and any social interactions (Denscombe Citation2010). Voice notes recorded the researcher’s thoughts.

With all observation there is a risk that events are open to interpretation by the researcher who can see what they want to see, possibly disregarding alternative interpretations which could prove important (Gray Citation2012). To address these issues and improve the trustworthiness of the findings (Einarsdottir Citation2005; Greenfield Citation2011), it was necessary to correlate data from all methods used such as photographs and semi-structured interview transcripts alongside observation notes to confirm findings (Denscombe Citation2010). Given the messy nature of play, at times there were difficulties in maintaining the focus of the study on the participants and their play. In Forest School the challenges were around the overlap of play and adult-led activities, whilst in Forest Kindergarten interactions between group members also had to be taken into consideration.

Semi-structured interviews

Informal semi-structured interviews were carried out after each observation and focused on gaining an insight into children’s play choices and actions (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). Used in previous Forest School research with young children, it was important to reach a shared understanding of the significance of what was observed, especially as the researcher’s interpretation may be different from the child’s meaning (Fargas-Malet et al. Citation2010). An open questioning style, such as ‘Tell me about … ’, was used here to glean background information, confirm the researcher’s understanding of the play observed, and to ask follow-up questions (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015; Denscombe Citation2010).

By locating the conversation in the child’s experiences and the images (Smith, Duncan, and Marshall Citation2005) the researcher was able to ask questions relating to the play observed as a way of gaining a deeper understanding of the child’s experiences and preferences such as, where they like to play, the places that are important to them, what they like to play and any resources or toys they like to play with (Brinkmann and Kvale Citation2015). The semi-structured interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and then cross-referenced with observation data for further confirmation (Clark and Moss Citation2001, Citation2005). In the Danish case the lead adult provided a translation, which although had the potential for bias was preferable to having no understanding.

Findings

Data collected from observation and semi-structured interviews and observations of the three children, and each adult in the two cases were analysed and compared. This study only focused on observing children’s ‘free’ play not activities that were designed or led by adults for children. Using the characteristics of play set out earlier, it was possible to identify the common features of the children’s play.

Description of the cases

In England, the focus of this study was the ladybird group. Consisting of 25 children, aged between 4 and 5 years took part in weekly, morning Forest School sessions. Five early years practitioners, all with early childhood undergraduate degrees and three had additional Forest School training to level 2 or Level 3. Other groups also use the Forest School at various times throughout the week. The three child participants in Forest School were Joe, Olivia and Caitlin. The lead practitioner in this study was called Kelly. In Denmark, Forest Kindergarten happened every day. With approximately 88 children aged between 3 and 7 years, attending daily, the focus of this study was the dragonfly group. Made up of 22 children and three pedagogues, each had an undergraduate degree. The three child participants in Forest Kindergarten were Oska, Luca and Anneka. The pedagogue who took part in the study was called Maja. According to the literature both cases are typical examples in each context.

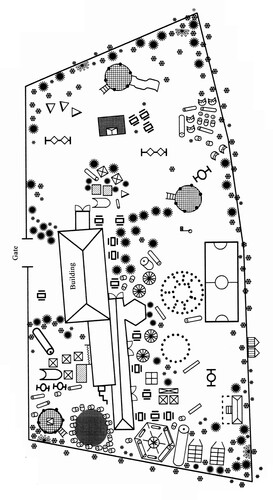

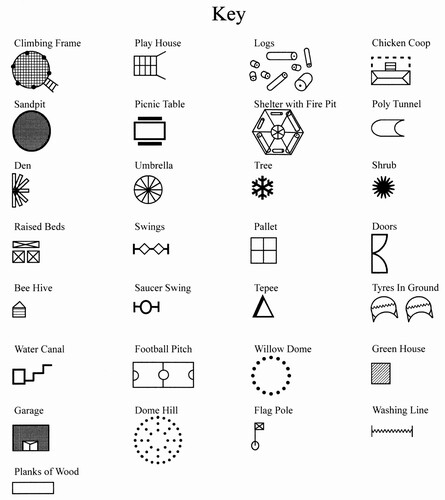

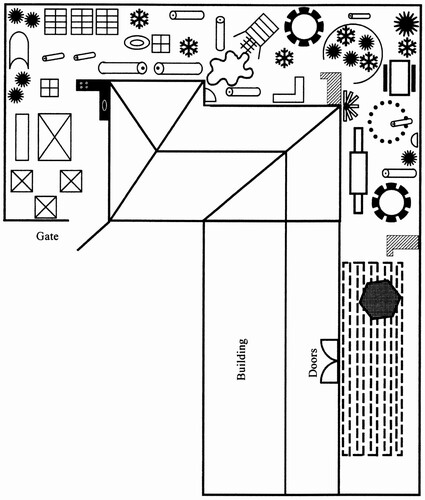

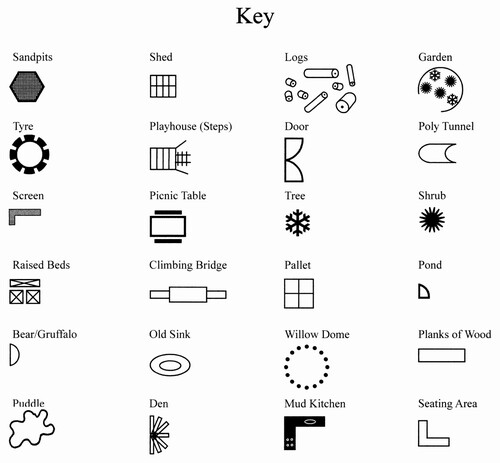

Mapping both locations reveals similar fixed equipment and places to play on each site, for example, the playhouse, sandbox, climbing frame trees and grass. However, the larger Forest Kindergarten site provided more variety of equipment and more open space, although there were more than double the number of children using that space. This means there is some duplication of equipment (multiple climbing frames and swings) that is not needed with fewer children, in the smaller-scale site of Forest School. Given the differences in size and scale, all the children in both locations moved about freely in the space available.

Differences between the two cases can be seen in what resources and loose equipment each setting make available (see and below) and their organisation. In Forest School () before each session the practitioners set up activities for the children to engage with. Some involved adult support, others were resources such as construction bricks, books and puzzles set out and referred to as ‘continuous provision’. In contrast, the pedagogues in Forest Kindergarten did not set out any equipment or organise activities for the children ( and ) .

The beginning

All observed sessions started with a circle time. In Forest Kindergarten, Maja asked the children ‘where are you playing today?’, ‘what are you doing today?’ or ‘who are you playing with’. Luca chose to climb trees, Oska chose to dig in the sandbox and Anneka chose to play with her sister in the playhouse. Interview data confirm that all three children chose places where ‘I like to play’ and what with. In Forest School, Kelly briefly explained the activities and continuous provision available, then asked the children ‘What would you like to play with?’ followed by ‘what would you like to do?’. Joe chose to play with puppets and Olivia chose the books. Caitlin chose to play in the ‘mud’ kitchen. Interview responses confirmed that all three children had chosen their ‘favourite thing’, suggesting that all the children found forest play fun and enjoyable (Meckley Citation2002). All six children seem to draw on their previous experiences and knowledge of the outside location and of what is available in each setting choosing places that are familiar, ‘we always play there’.

The difference in framing at the start of each session by the adults might have influenced the children’s responses. Maja’s questioning seemed to emphasise where what and who with, whereas Kelly focused on which activities and resources the children would play with. These differences can be linked to each setting’s pedagogical preference for either planning activities or focusing on the free play also identified in a similar study by Waite, Davis and Brown (Citation2006). Justifying their approach Kelly said she needed to ‘provide variety … ’, whereas Maja stated that she ‘did not plan activities for children but with them … they come from their interests and the environment’. Explanation of the activities and resources available may have influenced the children’s choices. In addition, children may have been influenced by peer choices.

Each session starts with the children choosing where to play and what to play with, so can be identified as child-initiated (Wood Citation2010). Both the adults interviewed were committed to children playing outside and were aware of its benefits for holistic child development. Even though Kelly had planned activities and Maja had not, they behaved in similar ways, inviting the children to choose what they wanted to do, although the question framing suggests different underlying pedagogical principles. By providing and then explaining the activities Kelly’s behaviour was similar to that identified by Maynard (Citation2007a, 385) it was not overly ‘directive’ or ‘protective’ rather she was giving the children prompt, scaffolding the choices for those she identified as ‘inexperienced’. Maja took a different pedagogical approach and gave the children ‘time and space’ to make up their minds, as suggested in the pedagogical curriculum (MCE Citation2020), coming back to children who were undecided. With few visual and oral prompts the Forest Kindergarten children were more reliant on their previous experiences or peer choices.

Given that the fixed equipment was similar in each setting, one of the main differences between the two locations, apart from the scale, seemed to be the amount and variety of resources readily available in Forest School. Whilst the many resources, coupled with the adult explanation could have overwhelmed the Forest School children, the minimal resources in Forest Kindergarten could be unstimulating. Justifying her pedagogical approach, Kelly was clear she used the resources and equipment to provide ‘variety’. Alternatively, Maja was confident that the ‘natural environment would motivate the children’ and ‘activities come from the children’s interests’ supported by Gulløv (Citation2003) and Knight (Citation2009).

The subtle difference in pedagogical approaches between Kelly and Maja suggests that each is allowing the children to make decisions within what they each consider to be acceptable, but adult-imposed boundaries (Waite, Davis and Brown Citation2006; Mackinder 2018). Both adults’ pedagogical decisions based on different values influenced the level of choice children had in each context and need further research.

Fixed equipment

Although and both show comparable fixed equipment, such as the sandbox, playhouse and climbing frame, they were not static but dynamic places. Children in both cases used them creatively as a focal point for their play, becoming familiar places where children could explore and experiment, playing games they created for themselves (Wood Citation2010). Especially noticeable in Forest School some spaces were allocated resources by practitioners, which contrasted sharply with the uncluttered, open spaces of Forest Kindergarten that seemed to open up the potential for child-initiated free play (Gulløv Citation2003; Tovey Citation2010). Closer analysis revealed that the children in both cases played in similar ways, initiating their own play. In the play observed, the fixed equipment provided spaces for children to play away from adults.

Toys, tools and resources

Even though the two contexts applied a different pedagogy regarding resourcing, all six children used items in their play. In Forest School where toys and resources had been set out by the practitioners Joe chose to play with puppets and Olivia chose the books. Choosing to play in the sandbox Oska needed tools ‘to help me dig’. He went off searching for a bucket and spade before returning to use them to dig tunnels and collect water. Caitlin, playing families in the mud kitchen, had no props to play with, so searched for bugs to be her ‘babies’, then looked for ‘leaves … to feed them’. Similarly, playing mums and babies, Anneka looked for a stick that she used as a ‘phone’.

Whilst some of these items such as books and spades had been provided by adults, other natural items such as leaves and sticks were provided by nature and then adapted by the children for their play. Items or tools such as the bucket and spade had a specific purpose, whereas others such as leaves and bugs did not. What is common to all these examples is that the children knew what they needed or wanted for their play, and then knew where to look for it. Children placed high importance on using items for their play, for example, Joe ‘needed the puppets’ and Oska ‘had to have (the) spade’, a specific tool needed for a self-assigned task. Their use enhanced the quality of their imaginative play.

Not using items in adult-prescribed ways, children were seen assigning their own meaning to objects. For example, Joe played with the puppets played in his own way, inventing his own story, using the bird puppets to ‘fly’, ‘zooming’ around ‘fast’ and ‘quick’. It was only when an adult intervened that he sequenced the puppets using the traditional narrative of chicken licken as he was asked, before resorting back to his own play. Caitlin and Anneka used natural items they had found, adapting them for different purposes in their play. Both examples show creativity and resourcefulness in how items were assigned meaning and significance. In addition, searching for and then using equipment resulted in them being moved around the site, often to unexpected places where they were used in unanticipated ways.

Whilst the fixed equipment provided familiar places for all children to play, the smaller play items provided adaptability and flexibility essential to the play. In both cases there was also a selection of much larger, items such as logs, pallets, planks of wood and tyres. Whilst in Forest School these items remained in the same places, in Forest Kindergarten, all three children at some points were involved in moving larger pieces around. Oska and friends moved logs and large branches into the playhouse, whereas Anneka and her sister moved them out, then pulled tables and chairs in. Luca and his friend dragged a metal goal into position before playing football.

The ability to be able to move items small or large to different places seemed important to much of the play observed, as the children adapted their environment to suit their play needs (Knight Citation2013). In the flow of their play the children were able to use places and equipment in the ways they wanted to, adapting what they had or finding something else to use or represent something else in their play (Pellegrini Citation1991). Whether this meant locating items or using those readily available, they all had their own ideas and played with the resources in their own ways and not always in the ways adults had planned (Wood Citation2010). Even though in Forest Kindergarten children were expected to source their own resources and equipment, however, even with many items provided for them the Forest School children did the same, often using items not as they were intended.

More evident in Forest Kindergarten than in Forest School the children were seen moving quite large loose items such as logs, branches, tables, chairs and a football goal. Whether items were used to set the stage of their play in the playhouse, or integral to their play such as the football goal, moving such large pieces of equipment required a level of confidence and experience (Pellegrini Citation1991) that was not seen in the Forest School children. Similar to Brostrom et al. (Citation2012) study, the frequency of visits over extended periods of time, especially from the age of three encourages children to be absorbed in their play, compared with children who are new to Forest School at four years old, and only attend weekly sessions. There was a clear difference in how the children from the two cases engaged with large non-fixed or moveable equipment. The Forest Kindergarten children took the opportunity to choose and then use resources in their own ways demonstrating a high level of independence, self-reliance and autonomy (Pellegrini Citation1991). More time allows children to return to play and places more frequently to complete their play, relive it and share these experiences (Brostrom et al. Citation2012).

In the spaces where the free flow of items was permitted the children had more opportunity and scope to develop their play in their own ways, experiment and be creative and resourceful. Supportive of this, the adults through low-level supervision, mostly allowed for flow and movement, showing that it can be difficult for adults to plan for children’s play (Wood Citation2013). However, both environments have been created by the adults, with space, time and resources that facilitate play (Wood Citation2010). Open-ended equipment was identified as ‘best’ for children to explore, adapt and be creative in their play expressing their own ideas (Bruce Citation1991; Knight Citation2013). In searching for and then using small pieces of equipment the children caused them to be moved around the site often to unexpected places where they were used in unanticipated ways. Crucially adaptability of resources allowed children to play independently from adults. Previous literature has not investigated children’s use of resources in forest play; therefore, more research into how resources and equipment is used by children in forest environments would be useful, especially those that are loose, adaptable and moveable.

Away from adults

As the spaces and large equipment were not always assigned meaning by adults, their nature was open and dynamic (Tovey Citation2010). Even when meaning was prescribed by adults, as part of the active process of their play children allocated their own meaning to the same places. Over the course of the week, spaces such as the playhouse and climbing frame were used differently by the children observed, for example, mums and babies, fairies and superheroes. The addition of other pieces of equipment, such as branches and tables brought into that space by the children, was then used in a variety of ways, adding another dimension to the play.

Observation showed that children’s play flourished in secluded places. Here they have the freedom to play how they want, totally immersed (Tovey Citation2010). Recognising the benefit for children’s holistic development, both Kelly and Maja intentionally minimised supervision in these play spaces, allowing the children space and time to play uninterrupted for extended periods (Kristjannson Citation2006). More so in Forest Kindergarten than Forest School because of all-day provision with pedagogues choosing to ‘only’ engage in ‘meaningful interactions’. Having space and time away from adult supervision without fear of unnecessary interventions, seemed to open up children’s play, as the children were afforded privacy and freedom to explore and develop play in their own ways, becoming absorbed and immersed in their play (Brostrom et al. Citation2012; Tovey Citation2010).

Adults have constructed forest play spaces according to their pedagogical understanding and safety regulations (Knight Citation2009). It also seems important that adults do not impose too many rules that could limit children’s freedoms and educational outcomes could shift the emphasis from child-initiated play to work (Waite, Davis, and Brown Citation2006). By standing back from the play, the adults could be seen as opening up space for children to develop peer relationships or friendships. Children were seen playing on their own or in peer groups. Being able to play on their own or with peers, uninterrupted allowed the development of complex play stories to develop (Bruce Citation1991).

Others

At the start of each session all the children’s choices may have been influenced by their peers. For example, Oska chose the sandbox because ‘his friends were playing there’ and Anneka chose to ‘play with my sister’. However, in Forest School apart from when their play pathways crossed with another child’s, all three participants played on their own. Conversely, observations of both Anneka and Oska showed them consistently playing in a group, even though this might not have consistently been co-operative play (Parten Citation1932). When Oska’s tunnel was collapsing, he called out for ‘help’ and was supported physically by his peers trying to ‘hold up the sides’. Then offering suggestions telling him to ‘build it up’, ‘dig quickly’ and ‘you need water’. Peer support, especially from mixed age groups in Forest Kindergarten, was seen to contribute to children’s social interactions with each other (Jensen Citation2011).

Seemingly an example of co-operative play (Parten Citation1932), Anneka supported her younger sister by telling her the ‘play story’, narrating future events (Bruce Citation1991). However, at the same time she was controlling the narrative, directing the play and telling her what to do. There was also an example of conflict in Anneka’s play when some of the older girls challenged her sister ‘you can’t play here, only mums can play here’. In addition to peers scaffolding learning for each other, some of the features of group play included sophisticated, social aspects suggesting that children were drawing on their previous knowledge and experience of social relationships, testing out rules and boundaries (Wood Citation2013).

Although the prevalence of children playing on their own in Forest School contrasted sharply with the group play seen in Forest Kindergarten, the kind of play in both cases was similar. This difference could be because Olivia and Joe had chosen to play with puppets and books, items that already had a meaning assigned thus potentially limiting their versatility. Caitlin’s family play, although similar to Anneka’s mums and babies, was solitary (Parten Citation1932). The location of the ‘mud’ kitchen hidden around a corner () compared with the more prominently placed playhouse () where Anneka played might be significant. Whilst providing a place away from adults it seems the ‘mud’ kitchen was also away from other children. Caitlin engaged with props in interactive and social ways as substitutes for others. Similar patterns more typical of the younger or inexperienced children (Parten Citation1932) were also seen in Olivia and Joe’s play, preferring to interact with toys rather than with their peers, supporting Kelly’s earlier claim. A contributing factor might be the adult-led activities, not observed as part of this study might mean children were occupied elsewhere, and not playing freely ().

In both cases, the open play, in familiar places, also away from adults seemed to make the children more self-reliant, autonomous and independent (Pellegrini Citation1991; Gulløv Citation2003). With children aged between 3 and 7 in Forest Kindergarten there is more scope for mixed peer group play than in Forest School with children aged four and five years old. A feature that emerges from the peer play but is also evident in the solitary play seen in Forest School is the use of play stories or narratives. More research into solitary and group play, especially mixed-age group play dynamics and its benefits especially for peer scaffolding is warranted.

Story and narrative

All the children, in both cases, were heard articulating their ideas, telling stories or narrating events. By verbalising what was happening in the sand tunnels Oska was thinking through his problem out loud (Vygotsky Citation1978) and working through the problems he was encountering. He was able to share his situation with his peers who supported him, offering their help and advice as they jointly problem solved. Putting their thoughts and plans into action, in the flow of the play the problem was very real (Wood Citation2010).

Similar to Oska, when Luca was climbing his favourite tree, he also was trying to think through his challenges. He could be heard saying ‘this tree is easy for me to climb’. He explained the next tree was ‘harder to climb’ and ‘some days I can climb it … other days I can’t … they are too difficult’ so I start on the ‘easiest to climb tree’ before I ‘climb the harder trees’. However, as he went on, he seemed to be speaking his thoughts out loud to himself, saying ‘Come on’, ‘you can do this’, ‘higher’, ‘reach up’, ‘now this foot here’ … as he thought through his movements articulating them as he placed a hand or foot on a branch. Thinking out loud also appeared to help him focus on the task and helped him achieve his goals (Bruce Citation1991).

Sometimes these narratives seemed like well-rehearsed scripts. Caitlin, playing on her own spoke to her babies ‘It’s time for breakfast’ as she fed them, and narrated events of the play ‘It’s time to eat’, then ‘It’s time to wash up’ before ‘Let’s put this away’, sequencing the events of the play out loud, allowing her to think through what she was doing (Vygotsky Citation1978). Similarly, Anneka directed the play with her sister, who was the baby ‘getting up’ then ‘eat up’ before ‘tidying up’ and then ‘going to the shops’. Anneka continued directing her sister ‘Let’s go over here now … ’ and ‘Let’s look for chalk so we can draw on the walls’. Anneka’s use of story was multipurpose as it served to inform her sister about the play, was a way of getting her sister to join in, as well as a way of her choreographing and directing the outcome of the play (Vygotsky Citation1978). Caitlin and Anneka’s play are examples of children self-managing and self-regulating by setting their rules and boundaries (Bruce Citation1991).

Story or play narratives were a central feature seen in all the children’s play (Bruce Citation1991) and used for a range of purposes in all the play observed. Caitlin and Anneka used their narratives to structure and direct the pretend play, each taking a leading role. Luca used a narrative to motivate himself, thinking aloud and giving himself instructions. Anneka and Oska negotiating and co-ordinating members of a group, ‘thinking out loud’ allows the children to articulate their thought processes as ideas and communicate them to their peers, which is an integral part of learning (Vygotsky Citation1978). In both cases the adults were not involved in the play, meaning that children had the time and space to explore situations, their friends and themselves at their own pace (Vygotsky Citation1978). The narrative appears to be the verbal glue that holds the play together. More investigation into how narratives inform and support play in Forest School and Forest Kindergarten, especially peer play without adults would be informative.

Conclusion

Although only small scale, this study was concerned with gaining a better understanding of children’s play in Forest School and Forest Kindergarten. Initially the data showed some differences between the two cases; however, after digging deeper and drawing on the literature there are many significant similarities.

Observation shows children initiating their own play, being actively involved in play, and making decisions in the flow of their play. This was enabled by each adult’s pedagogical decision to stand back from the children and give them time and space that allowed them to play in their own ways. However, how far children were permitted to make decisions, within parameters was previously decided by each adult involved, and raised questions over values. Adults in both cases made pedagogical decisions to create environments where it was possible for children to develop these skills.

These different boundaries seem linked to the values and purpose of early childhood education, although more research is needed to explore this aspect further. Regardless of whether children were attending daily in Forest Kindergarten or weekly in Forest School, they remembered their favourite places to play. All the children chose to play in familiar places. Although static, the playhouse, sandbox and climbing frames provided open, dynamic places where children played their own games in their own ways. Whether on their own or in groups all examples show children playing in places away from adults (Tovey Citation2010). Whilst Oska and Anneka played with their peers, sometimes playing away from adults meant playing away from peers, for example, Luca’s play was similar to Caitlin, Joe and Olivia’s as at times all four played on their own. Looking at children’s play over a longer time period would help identify whether solitary play was age-related and developmental, or more indicative of pedagogy and environment.

Choosing to play in places away from adults, the children showed evidence of being self-reliant, and independent. In Forest Kindergarten children chose to play with their peers. Stories and play narratives supported both individual and peer play, at times providing structure, direction, motivation and support, holding the play together. By standing back from children’s play, pedagogues and practitioners allowed the children time and space for this to happen. Resources, whether provided by adults, or found were frequently used in fluid and flexible ways that were ‘new’ to the children, and their moveable nature warrants further investigation. All the children were absorbed and involved in their play (Wood Citation2010), often self-managing and self-regulating by setting their own goals, rules and boundaries (Bruce Citation1991).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Brinkmann, S., and S. Kvale. 2015. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. London: Sage.

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. London: BERA.

- British Educational Research Association Early Years Special Interest Group. 2003. Early Years Research: Pedagogy, Curriculum and Adult Roles, Training and Professionalism.

- Brostrom, S., T. Frokjaer, I. Johansson, and A. Sandberg. 2012. “Pre-School Teachers’ View on Learning in Preschool in Sweden and Denmark.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 590–603. https://www.researchgate.net/piblication/265520954_Preschool_teachers'_views_in_Sweden_and_Denmark

- Bruce, T. 1991. Time to Play in Early Childhood Education. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Clark, A., and P. Moss. 2001. Listening to Young Children. The Mosaic Approach. London: National Children’s Bureau and Rowntree Foundation.

- Clark, A., and P. Moss. 2005. Spaces to Play. More Listening to Young Children. Using the Mosaic Approach. London: National Children’s Bureau and Rowntree Foundation.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2011. Research Methods in Education. Oxon: Routledge.

- Cree, A., and M. McCree. 2012. A Brief History of Forest School Part 1 Horizons 60. Derbyshire: The Institute for Outdoor Learning Forest School Association.

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A., S. Edwards, and H. Widdop-Quinton. 2013. “Child-Framed Video Research Methodologies: Issues, Possibilities and Challenges for Researching with Children.” Children’s Geographies 13 (3): 343–356.

- Davis, B., and S. Waite. 2005. ‘Forest Schools: An Evaluation of the Opportunities and Challenges in Early Years’. Plymouth: University of Plymouth.

- Denscombe, M. 2010. The Good Research Guide. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- DfE (Department of Education). 2017. Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage. London: DfE.

- Docket, S., B. Perry, and E. Kearney. 2013. “‘Promoting Children’s Informed Assent in Research Participation’.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (7): 802–828.

- Douglas, J. 1976. Investigating Social Research: Individual and Team Field Research. London: Sage.

- Eastwood, G., and H. Mitchell. 2003. An Evaluation of the First Three Years of the Oxfordshire Forest School Project. Oxford Brookes University.

- Einarsdottir, J. 2005. “Playschool in Picture: Children’s Photographs as a Research Method.” Early Childhood Development and Care 175 (6): 523–541.

- Else, P. 2009. The Value of Play. London: Continuum.

- Fargas-Malet, M., D. McSherry, E. Larkin, and C. Robinson. 2010. “‘Research with Children: Methodological Issues and Innovative Techniques.” Early Childhood Research 8 (2): 175–192.

- Fjortoft, I. 2004. “Landscape as Playscape: The Effects of Natural Environments on Children’s Play and Motor Development.” Children, Youth and Environments 14 (2): 21–44.

- Flick, U. 2014. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- FSA (Forest School Association). 2019. www.forestschoolorganisation.org

- Garrick, R. 2009. Playing Outdoors in the Early Years. London: Continuum.

- Gray, D. 2012. Doing Research in the Real World. London: Sage.

- Greenfield, C. 2011. “Personal Reflection on Research Process and Tools: Effectiveness, Highlights and Challenges Using the Mosaic Approach.” Australian Journal of Early Childhood 36 (3): 109–116.

- Gulløv, E. 2003. “Creating a Natural Place for Children: An Ethnographic Study of Danish Kindergarten.” In Children’s Places: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, edited by K. Fog Olwig and E. Gulløv, 23–38. London: Routledge.

- Hughes, B. 2012. Evolutionary Playwork. London: Routledge.

- Jarvis, P., A. Brock, and F. Brown. 2014. “Three Perspective on Play.” In Perspective on Play. Learning for Life, edited by A. Brock, P. Jarvis, and Y. Olusoga, 12–41. Oxon: Routledge.

- Jensen, J. 2011. “Understanding of Danish Pedagogical Practice in Cameron.” In Social Pedagogy and Working with Children and Young People. Where Care and Education Meet, edited by C. Cameron and P. Moss, 141–159. London: Jessica Kingsley Pub.

- Knight, S. 2009. Forest School and Outdoor Learning in the Early Years. London: Sage.

- Knight, S. 2012. Forest School for All. London: SAGE.

- Knight, S. 2013. “The Impact of Forest School on Education for Sustainable Development in the Early Years in England.” In International Perspectives on Forest School, edited by S. Knight, 1–11. London: Sage.

- Kristjansson, B. 2006. “The Making of Nordic Childhoods.” In Nordic Childhoods and Early Education: Philosophy, Research Policy and Practice in Denmark, edited by J. Einarsdottir and J. Wagner, 13–42. Connecticut: Information Age Publishing Inc.

- Mackinder, M. 2017. “Footprints in the Woods: Tracking a Nursery Child Through a Forest School Session.” Education 3-13 45 (2): 176–190.

- Massey, S. 2002. The Benefits of a Forest School Experience for Children in their Early Years. Swansea: Unpublished Report University of Wales.

- Maynard, T. 2007a. “Forest Schools in Great Britain: An Initial Exploration.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 8 (4): 320–330.

- Maynard, T. 2007b. “Outdoor Play and Learning.” Education 3-13 35 (4): 305–307.

- McCree, M. 2019. “When Forest School Isn’t Forest School.” In Critical Issues in Forest School, edited by M. Sackville-Ford and H. Davenport, 3–20. London: SAGE.

- McCree, M., and J. Cree. 2012. “Forest School: Core Principles in Changing Times.” In Children Learning Outside the Classroom. from Birth to Eleven, edited by S. Waite, 222–232. London: Sage.

- Meckley, A. 2002. “Observing Children’s Play: Mindful Methods.” In A Paper Presented to the International Toy Research Association, London, August 13, 2002.

- Merriam, S. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. London: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Ministry for Social Affairs (MSA). 2004. Lov on paedagogiske laereplaner (Act on Curriculum: The Day Care Act). Copenhagen Ministry for Social Affairs.

- Ministry for Social Affairs (MSA). 2014. [Revised] Lov on paedagogiske laereplaner (Act on Curriculum: The Day Care Act). Copenhagen Ministry for Social Affairs.

- Ministry of Children and Education (MCE). 2020. The Strengthened Pedagogical Curriculum. www.emy.dk/dagtilbud MCE.

- Ministry of Higher Education and Science (MHES). 2014. The Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity.

- Moyles, J. 2010. The Excellence of Play. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Murray, R., and L. O’Brien. 2005. Such Enthusiasm – A Joy to see: An Evaluation of Forest School in England. Surrey: NEF Forest Research.

- O’Brien, L., and R. Murray. 2006. A Marvellous Opportunity to Learn: A Participatory Evaluation of Forest School in England and Wales. Surrey: Forestry Commission.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). 2014. Education Policy Outlook Denmark. www.oecd.org/edu/policyoutlook.htm.

- Parten, M. 1932. “Social Participation among Pre-School Children.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 28 (3): 136–147.

- Pellegrini, A.D. 1991. Applied Child Study: A Developmental Approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Reed, T., and M. Brown. 2000. “The Expression of Care in the Rough and Tumble Play of Boys.” Journal of Research in Child Education 15 (1): 104–116.

- Saracho, O. 1991. “The Role of Play in the Early Childhood Curriculum.” In Issues in Early Childhood Curriculum, edited by B. Spodek and O. Saracho, ix–xii. New York: Teachers College Press.

- SCAA (School Curriculum Assessment Authority). 1996. Nursery Education: Desirable Outcomes for Children’s Learning on Entering Compulsory Education and Employment. London: Schools Curriculum Authority.

- Smith, A., J. Duncan, and K. Marshall. 2005. “Children’s Perspectives on Their Learning: Exploring Methods.” Early Child Development and Care 175 (6): 473–487.

- Stake, R. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage.

- Sutton-Smith, B. 2001. The Ambiguity of Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Swarbrick, N., G. Eastwood, and K. Tutton. 2004. “Self-Esteem and successful interaction as part of the Forest School project.” Support for Learning 19 (3.

- Tovey, H. 2010. Playing Outdoors: Spaces and Places, Risk and Challenge. Berks: Open University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Mental Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wagner, J.T., and J. Einarsdottir. 2006. “Nordic Ideals as Reflected in Nordic Childhoods and Early Education.” In Nordic Childhoods and Early Education: Philosophy, Research, Policy, and Practice in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, edited by J. T. Wagner and J. Einarsdottir, 1–12. Connecticut: Information Age Publishing.

- Waite, S., B. Davis, and K. Brown. 2006. Forest School Principles: Why We Do What We Do. (Final Report). Devon: University of Plymouth, EYDCP.

- Wall, S., I. Litjens, and M. Taguma. 2015. Early Childhood Education and Care Pedagogy Review. London: DfE, OECD. www.oecd.org/edu/earlychildhood

- Wellings, E. 2012. Forest School National Governing Body Business Plan 2012. Carlisle: Institute for Outdoor Learning. Accessed 20th April 2018. www.outdoor-leanring.org.

- Williams-Siegfredson, S. 2012. Understanding the Danish Forest School Approach. Early Year’s Education in Practice. Oxon: Routledge.

- Wood, E. 2009. “Developing a Pedagogy of Play.” In Early Childhood Education. Society and Culture, edited by A. Anning, J. Cullen, and M. Fleer, 27–63. London: Sage.

- Wood, E. 2010. “Developing Integrated Pedagogical Approaches to Play and Learning.” In Play and Learning in the Early Years, edited by P. Broadhead, J. Howard, and E. Wood, 9–26. London: Sage.

- Wood, E. 2013. Play, Learning and the Early Childhood Curriculum. London: Sage.

- Yin, R. 1994. Case Study Research. Design and Methods. London: Sage.