ABSTRACT

Pupils' wellbeing in school can impact their learning, yet research into this topic is often from adults' perspectives. From a constructivist approach (where knowledge is shaped by human experience), the lack of child view on their well-being in schools is a significant gap in the literature, particularly from underrepresented groups including autistic pupils. This article is a small-scale case study with three child participants aged 7–8 years. To capture child voice, research tools were created by the participants followed by discussions to understand the student's intention. Two key themes emerged as important to well-being: social inclusion and school environment. This study demonstrates how child-created tools can be implemented in practice to truly ‘hear’ the voices of underrepresented groups. By empowering child voice in educational research, actions/implications for schools and their staff originate from the very individuals most affected, thus enabling child and school priorities to be better met.

Introduction

Although an increasingly important area of research, studies exploring children's well-being are often designed with the preconception that children simply do not understand this concept and what this means in their own life context. Therefore, there is a misconception that these children are unable to actively contribute to research studies aiming to find ways to improve their well-being (Kyriacou, Citation2012). When input on behalf of children is included, it is often from those close to them (i.e. what parents think their children feel) rather than going directly to the children, or only represents the voices of those children who are fluent in their communication (Marquez & Main, Citation2021). This is particularly the case for children with disabilities such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) with recent research still focusing on the views of parents in identifying what can support their child's well-being (Griffin & Gore, Citation2023). As a result, strategies to support student well-being do not have key input from the very children these strategies were directed towards and can lead to children lacking agency, particularly in educational research (Facca, Gladstone, & Teachman, Citation2020; Lloyd & Emerson, Citation2017). This research aims to address this gap by following a Constructivist approach to aid autistic children to share their views on what they feel improves their well-being, It uses data gathered from child-friendly tools which support students in sharing these views. Supporting young autistic students to contribute to the conversation enables a better understanding of the actual factors influencing well-being in the school environment.

Well-being covers many different areas of life including health, social relationships, academic and resilience (Kansky & Diener, Citation2017). However, it is also an ambiguous, under-theorized and poorly defined term (Axford, Citation2009). Baldwin, Sinclair, and Simons (Citation2021) highlight an increasing focus on the well-being of others in research but conclude that defining what this refers to is key. An initial definition from the World Health Organisation (WHO, 1948 in Bourne, Citation2010, p. 15) refers to ‘health (as) the state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing’; therefore, well-being is seen as something to strive for and very important to health. Furthermore, there are two main ways in which well-being can be considered: ‘subjective’ which focuses on self-reported views of well-being, often on a day-to-day basis; and ‘psychological’ which is objective, often using scales and questionnaires to provide a measure (Arslan & Coşkun, Citation2020; Department for Education [DfE], Citation2020a, p. 24). Despite the various objective instruments available, finding an accessible and reliable way to do this is not straightforward and often a challenge for students with diverse needs; especially those whose very disability limits these important communication skills. In one of the few studies exploring well-being with autistic individuals, Redquest et al.’s (Citation2020) study aimed to assess the well-being with quantitative measures, but these authors acknowledge the limitation that quantitative data does not sufficiently account for individual experiences. Also, with an age range of 4–18 years old, individual experiences of well-being may be distinctly different, yet participants could have the same quantitative score. Therefore, this research aims to provide an alternative to the use of quantitative data to show how subjective tools can be used to support young autistic students in helping them to share their individual views on their own well-being.

Literature review

Well-being is a current trend in the education sector and the impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic has rightly continued to place it as a high priority for educational staff and researchers. In 2021, the Department for Education (DfE) offered a grant for eligible state-funded schools to train a staff member to become a senior mental health lead to develop and implement a whole school approach to mental health and well-being, with a commitment that all schools will use this offer by 2025. More so than previously, schools have become the main place that students can be supported in their mental health and well-being. Several mental health charities have suggested ways schools can measure and support pupil well-being (including Anna Freud Centre, www.annafreud.org and Place to Be www.place2be.org.uk). The CORC (Child Outcomes Research Consortium), a project of Anna Freud: National Centre of Children and Families, includes questionnaires answered by the pupils, rather than just the adults (parents, practitioner or teacher) to present different perspectives. In accordance with The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, Citation1989), children have the right to ‘express their views, feelings and wishes in all manners affecting them, and to have their views considered and taken seriously’ (Article 12, p. 5). However, there are differences in the ‘aspects of wellbeing that children prioritise compared to adults’ (DfE, Citation2010, p. 2). Children's subjective well-being can be hard to accurately determine and capture in research due to reasons such as a power imbalance between children and adults, difficulties in discussing abstract concepts or finding age-appropriate tools (Facca et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is important to find tools that can address these gaps for use with a range of abilities and ages.

Using schools as sites for research can also contribute to this imbalance (Kirby, Citation2020). While in school, children have expectations from adults about their behaviour, actions and outcomes; as a result, they may wish to mirror these expectations (Kirby, Citation2020). Therefore, school-based research on this topic can be skewed as children might share their views on well-being through adult-created expectations, rather than their own subjective feelings with the risk of stating things they feel adults may not wish to hear. However, there is a balance to be struck. This article recognizes the importance of the school environment as a research site because of the amount of time children spend there and the fact that student well-being is unavoidably linked to their school experience. Data collected in schools needs to follow ethical considerations, but if ethical practice is followed and the right research methods are used, hearing directly from pupils can be achieved and provide huge insight by providing a perspective which is often unheard.

Dockett, Perry, and Kearney (Citation2013, p. 803) agree that educational research is ‘best reported by those experiencing’. This is especially true for groups of children who may be reluctant to open up to unknown researchers, including those children who are young or with disabilities. The ability to freely share views is dependent on tools and research methods appropriate for these hard-to-reach groups, thus enabling all individuals the opportunity to express themselves. To overcome the methodological limitations, this article focuses on the creation and trial of child-friendly tools focusing on subjective well-being. The aim is to support underrepresented groups in sharing their point of view by exploring a small sample of autistic Year 3 pupils in a large primary school in England. Empowering children to explore their own views towards student well-being can create a unique perspective, and as a result, can improve provision and educational practice by the adults (Bourke, Citation2017).

Roles in schools in promoting positive student well-being

Post-pandemic priorities reflect heightened concerns about children's well-being in education policies (DfE, Citation2020a). As a result, the British Government have placed an increased emphasis on the role of schools to find ways to support student well-being, and primary school is a key environment for this focus (DfE, Citation2020a). If schools can empower pupils from a young age, children can be supported to develop self-regulating strategies and an increased awareness of their own needs (DfE, Citation2022).

The potential impact beyond education is also worth exploring. Early intervention is key to lessening the long-term impact on health services (DHSC & DfE, Citation2017), one of which is mental health services. However, this is not straightforward, and many schools have had to seek help to support their pupils due to the decreased availability of externally provided assistance. In a 2020 survey, The National Association of Headteachers (NAHT) and mental health charity, Place2Be, revealed a rising number of schools that have had to commission professional help for children's mental health issues since 2016 (NAHT, Citation2020). This contributes to a long waiting list for Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) with up to 33% of referrals still waiting for any contact across 2019–2020 data (NHS Digital, Citation2019; Citation2020). Although schools do work towards supporting mental health and well-being, this is just one of many priorities which teachers can feel undertrained to provide (Danby & Hamilton, Citation2016).

Despite this lack of training or confidence of staff, schools can hugely aid children's sense of well-being by being ‘supportive environments’ (Drew & Banerjee, Citation2019, p. 101), highlighting awareness of and embedding supportive responses for all children. Children's ability to constructively express their emotions when in primary school can be linked to their current well-being, as well as in the future (Amundsen, Riby, Hamilton, Hope, & McGann, Citation2020). Most schools do see the importance of improving student well-being for pupils and schools alike; what is less clear is how to engage with all pupils to help adults better understand an individual's view on their well-being and how to support positive strategies to develop greater resilience.

Impact of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

In England, the SEND Code of Practice: 0–25 years (DfE & Department of Health [DoH] Citation2015), is used as guidance for professionals in England and states that educational provision for pupils with Special Education Needs and Disabilities (SEND) must ‘promote wellbeing’ (p. 7). However, an individual's SEND can also impact on the ability of a child to discuss abstract concepts such as well-being. For children with a diagnosis of ASD, the very nature of their disability typically means difficulties in communication and regulating emotions, which can make conversations even more challenging (Goldsmith & Kelley, Citation2018). For example, Baron Cohen (Citation2001) theorizes that children with autism have delays in understanding Theory of Mind (that views of others can be different from what they experience) which Hale (Citation2004) has shown to be linked with the ability of autistic individuals to develop social communication skills. These skills are often fundamental to conceptualizing abstract ideas such as well-being. Therefore, an alternative method to aid discussion of abstract concepts is needed when exploring the views of autistic young children.

Autistic pupils bring many strengths but can also have difficulties beyond communication limitations when learning in schools and settings. For example, diminished social literacy, poor emotional control and, in some cases, extreme emotional outbursts can have an impact on learning (Goldsmith & Kelley, Citation2018). Limited understanding of peer relationships and how these are reciprocated, can lead to isolation and is a social challenge for this group (Petrina, Carter, & Stephenson, Citation2014). When an autistic child cannot actively regulate their emotions, they may not feel calm and safe in their environment which could impact their peer relationships and sense of belonging, creating a potential negative impact on their education as well as a wider barrier to their well-being (Bailey & Baker, Citation2020). This can lead to mental health issues, such as depression and self-harming (Tierney, Burns, & Kilbey, Citation2016), all of which are key to student well-being. However, frequently these struggles are assumed by adults to be the same for all autistic children, leading to a ‘pick and mix’ of approaches, often with limited success. Therefore, it is important to find ways to hear directly from individual autistic pupils about their well-being to consider how best to provide support in a child-centred way (Benevides et al., Citation2020).

Beyond the individual student, schools can also benefit from learning the views of autistic children. Russell et al. (Citation2022) found there was a 787% increase in autism diagnosis from 1998 to 2018. They concluded that it is most likely that greater reporting and application of diagnosis was the main factor for the increases (Russell et al., Citation2022). As a result, consideration of this increase and how it might look in a school population is key. The National Autistic Society's 2021 School Report states that a ‘whole school approach’ is needed for supporting autistic pupils’ well-being (p. 15). The report also highlights that an autistic pupil ‘may require greater … wellbeing provision’ (National Autistic Society, Citation2021, p. 26). Therefore, this article shares the findings of how the first author overcame these challenges, using innovative tools, to support students to discuss their well-being and subsequently inform school practice on ways to improve it.

Materials and methods

Methodological approach

Constructivism theorizes that knowledge is changeable depending on how events are interpreted and moulded by human experiences (Pegues, Citation2007). This aligned with the researchers’ aims in considering different perspectives towards student well-being; as a result, the research tools were designed to facilitate and accurately capture the participants’ ‘voice’. Konu and Rimpela’s (Citation2002) School Well-being Model highlighted school conditions, social relationships, means of self-fulfilment and health status as themes to consider in relation to student well-being. This multi-dimensional model was used as an initial basis for the researcher in guiding the themes for this research (Tobia, Greco, Steca, & Marzocchi, Citation2019). Following an interpretivist approach, the participants’ curated much of the raw data through their own drawings and photography, which minimized the influence of others (Alharahsheh & Puius, Citation2020). When working with young children who have communication challenges, the added step of having the participants describe what their raw data means accurately more accurately established how the child wanted the data to be seen in the semi-structured interviews that followed. By taking a constructivist and interpretivist approach to data collection and research design, the research tools enabled open conversations which were designed to best support the accuracy of student's views.

Participants

A small-scale case study was used for this study. It was conducted after the third UK lockdown (from January 2021), once pupils had returned to full-time education (from March 2021). The opportunity sample was from one Year 3 class in the school the lead author was working in. The study chose to focus on children with ASD as this group often struggle with many of the issues linked to well-being as well as are underrepresented in research studies to date. Therefore, all children with a diagnosis of autism in the class were invited to participate and three agreed (as well as had parental consent). The three participants also had learning difficulties and prior concerns raised about their well-being in school by either the class teacher, parents, Special Educational Needs Co-Ordinator (SENCO) or Headteacher. Issues raised included concerns about social difficulties with peers and possible low self-esteem and all had concerns raised about the risk of exclusion or social isolation by school staff or parents. Although social difficulties or low self-esteem and well-being were identified by adults, consultation with the individual pupils had not happened as their disabilities made this difficult to do.Footnote1

The participants are described in (all identifying details have been changed).

Table 1. Participant information and methods used.

Ethical considerations

Obtaining consent from any young pupil can be challenging as children can be influenced by traditional authority roles in the school environment (Kirby, Citation2020). As all participants in this project had additional learning needs as well, an ‘open and honest’ distinction of what the researcher's role will be in the study was done for all participants (British Educational Research Association [BERA], Citation2018, p. 16); which was followed during the research process. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the authors.

Following consent from both the school and families (BERA, Citation2018), the child participants in this project were given an assent form in child-appropriate language in view of their diverse needs and young ages. Recent research concluded that, when working with young children, ‘consent should be negotiated continuously’ (Arnott, Martinez-Lejarreta, Wall, Blaisdell, & Palaiologou, Citation2020, p. 806) so an additional assent form was prepared for use at different stages in the data collection to continually confirm their willingness to be involved. The child participants also had the explicit option to halt their participation at any point (informed dissent) in the data collection.

Measures

Group preparation for data collection

Following parental consent, a group workshop was designed with the researcher supporting the participants to create a shared definition of the term ‘wellbeing’ and explore the research tools. All three child participants had the opportunity to ask questions about the project and discuss meanings. Ahead of the participants using the tools, they were trained in the purpose and application of these tools through unstructured sessions with the first author. This gave all participants the opportunity to try out the various tools and ask any questions of the researcher. Alice asked how much work she needed to do and was reassured it was as much as she wanted to do and that she could stop at any point. Once the participants understood the process, individual data collection followed with the three child participants over a four-week period. The tools used are described below.

Individual data collection

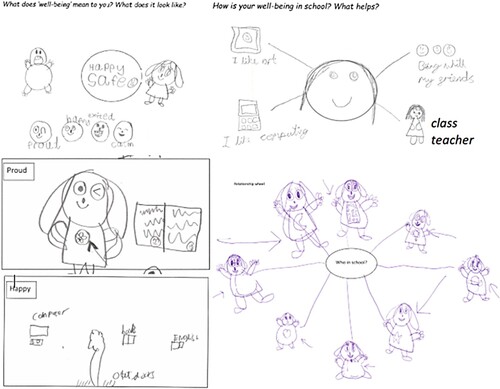

Data for this study was created by the child participants through a variety of research instruments including concept maps, drawings, and relationship maps (see ). All participants completed these individually with the researcher available in a quiet room. The sessions creating the research instruments were led by the participants so lasted between 20 and 45 min.

Figure 1. Selection of research methods used by each participant: (top two images) Concept maps from Lisa and Alice; (bottom left) ‘When I feel … ’ drawings from Lisa and Andy; (bottom right) Relationship map from Lisa.

Drawings were used in a variety of formats to encourage participants’ focus on a certain element. A concept map is an established research tool used to explore understanding of an item or task and therefore, was used as a research instrument here (Foley, Citation2015; McDonough & Sullivan, Citation2014). Participants were given a proforma with a prompt question to encourage them to draw what they feel helps with their well-being (see ). The researcher read out the prompt question and asked the children to draw what helped with their well-being. All participants were able to do this without support.

Each participant used ‘When I feel’ drawings and relationship maps as well to convey their views. Rather than written tasks, drawings allowed the participants to ‘explore and communicate their understandings’ without any barriers brought by communication difficulties (Einarsdottir, Dockett, & Perry, Citation2009, p. 218). The ‘When I feel … ’ drawing task used the key vocabulary established in the pre-session of ‘happy’, ‘safe’ and ‘proud’ so the participants could illustrate situations or environments that they associate with these feelings (see ). In the relationship maps (see ), children drew pictures of their family and friends and the connections they had to these people.

Finally, semi-structured interviews followed each of the methods described above to check understanding of the child participants’ perspectives and to ensure the child's views were accurately captured. These were conducted separately with the researcher using an interview schedule to lightly structure the discussion. The Constructivist and Interpretivist approach of this project valued the qualitative data from interviews (Powney & Watts, Citation2018). As the aim of this project was to encourage student voice rather than limit it, the interviews were semi-structured and audio recorded (after consent was re-confirmed). This limited the researcher's influence as it encouraged the pupils to openly share their views and hence, was lightly scheduled. The interview discussion aimed to encourage the child participants to talk about their raw data and the analysis endeavoured to ‘present their results honestly’ (Wager & Kleinert, Citation2011, p. 310). The participants were asked open-ended questions which focused on their completed figures. Example questions were: ‘Can you tell me about what you have drawn?’ or ‘Tell me who this person is and why you have drawn them?’. Over a period of a month, all three participants completed concept maps, a ‘When I feel … ’ drawing task, photograph sessions and relationship maps.

Data analysis

Because the semi-structured interviews were the participants’ explanation of their drawings, the raw data consisted of their direct and unfiltered descriptions of what they had drawn. Therefore, the research focused on this data; hence, following consent each interview was recorded, transcribed and checked for accuracy (Elliott, Citation2018). Thematic analysis was used to manually code key phrases or words mentioned in the interviews. The initial words and phrases that came up most frequently included (in order of frequency): lunch/break time, classroom environment, peer friendships, school staff, schoolwork and family. The author then used this coding from the semi-structured interviews to create themes and subthemes. The themes of social inclusion and safe spaces in school emerged from the data of the raw data and are therefore discussed next.

Results

Constructivism states knowledge is created by the experiences of an individual. The results of this qualitative study use the words and documents created by the individual participants which are linked to their experiences of school. School experience is a significant part of a student's life and subsequent views of well-being at their age (Anderson & Graham, Citation2016). What is less clear is how individuals interpret these experiences, which is why it was key that the participants had the opportunity to explain their drawings and data. This links to the interpretivist aim to reduce the influence of others on the meaning of that data. This becomes an even wider consideration with the autistic participants in this study whose views are already underrepresented, as discussed in the introduction and literature review. With these methodological lenses, two main themes emerged from the results: social inclusion and safe spaces in school.

Theme one: social inclusion

Social relationships, including peer friendships, family relationships and those with teaching staff, will be discussed first. This also includes the impact of peer relationships and unstructured time in the school day (e.g. lunch time).

In , Lisa included many peers in her relationship map. She included arrows between different children but was not able to verbally explain why she had the arrows in different ways. In contrast, Alice only includes her closest peer, parent and teacher (see ). Both included their peers at school as important to their well-being, particularly Grace who appeared in both of their relationship maps. Lisa stated, ‘there is love inside Grace's heart and she gives it to me’. This shows an appreciation of these relationships and recognition of peers as friends, despite the concerns about a lack of friends which was often raised by adults. However, it could be that Lisa's inclusion of many peers as her friends on her relationship map is a simplistic view of what friendship is as she may feel these individuals are her friends, but the feeling may not be reciprocal. Despite this possible lack of understanding, Lisa states her social relationships do contribute to her well-being.

The selectiveness of these peer relationships, and consequent understanding of what friendships are, is important to note as well. In terms of Alice's relationship map, only one child features (Grace). Alice said, ‘I really like Grace because she is really kind, and she helps people when they are upset and stuff.’ and ‘Grace makes me feel happy.’ Additionally, Alice has picked out Grace's empathy and social skills as an area she likes about her which could suggest she recognizes this as a skill. Lisa seems to be less inherently aware of social relationships of others and this can be seen in how she described her relationships with two teaching assistants who work with her as being friends:

I drew Miss Finn and her good friend Mrs Green.

[pause] … because they are friends. They like being with each other and they like holding hands.

Despite the parental concerns raised around the risk of exclusion and social isolation (see selection criteria above), all three participants appeared to sincerely value their friendships, although in unusual or detached ways. These include a simplistic view what friendships are, lack of reciprocity and/or detachment as seen in Andy's preference to just watch Year 4 children playing football, feeling unable to join them. When asked to explain his drawing, he explained:

Umm, watching other people.

Like, playing

Yeah

Good. I watch the Year 4s play football.

Theme 2: safe spaces in school

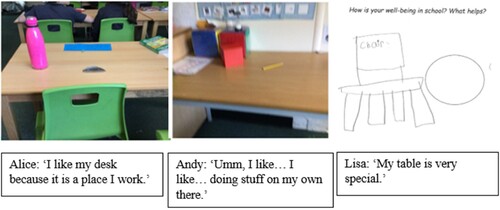

Individual workspaces were included across the participants’ data, with all three capturing and discussing their desk areas (see ). The participants appeared to value this dedicated area and stated their connection to their desk spaces. All three highlighted the importance of their workspace; choosing to discuss this first when talking about the photos taken in . The use of ‘my’ in all of their comments in shows the connection and ownership of the space. Much of the language used in the comments about their individual spaces focuses on the usefulness of their workspace within a classwork context.

To the child participants, safety was represented within the feeling of belonging and their social relationships linked with being at school. Lisa connected the arrival to school with feeling safe, Andy recorded playing with friends, and Alice drew an art therapy session with her best friend in . Finally, evidence of strategies to support were present in the data collected and can also come from feeling safe in the environment (Brodovsky & Kiernan, 2017). Often, young autistic children can rely on strategies and others to help regulate their emotions (Cibralic, Kohlhoff, Wallace, McMahon, & Eapen, Citation2019) and this was true of the sample. Lisa explicitly references using the school's emotional regulation resource and puts herself as ‘greenish yellow’ during the semi-structured interview; (i.e. the use of colours is a commonly used emotional regulation tool with red referring to anger, blue referring to sadness, yellow referring to nervousness and green referring to happy/comfortable). Andy refers to his toys being able to ‘cool [him] down’.

It is interesting to note that each student could clearly identify the area or ways to help support their well-being. Whether this was a space or technique, they each could state what worked for them. Some of the examples cited were known and supported by the school (as part of the whole school ethos), but other aspects were not identified or even recognized by adults. For this group of pupils, the combined impact was helpful and provided a safe place to learn. Therefore, it is key to build independence in self-regulation, but fulfilment is also important to consider ().

Discussion

Each of the two themes explored is drawn from data directly from the autistic pupils regarding their well-being. As young autistic children, their voices are often unheard, yet a priority to understand for adults, schools and government bodies. As such, these bodies are over reliant on what adults may think the key issues are instead of going through a less straight forward process of trying to find a way to enable all those affected by government policy an equal opportunity to have their voices heard. This results in a less than inclusive picture of what the concept means to these hard-to-reach groups, as past research is largely reliant on what well-intended ‘others’ believe, sometimes with the mistaken lack of belief in the emerging positive outcomes that do exist. If we are to truly grasp the important ethos of student voice in decision-making within schools, the perspectives of all groups must be better listened to. This article proposes one way to do so by sharing innovative methods used to support autistic students share their understanding of well-being.

One of the most interesting elements to note amongst these themes is the social-centredness of the comments from the participants, which is somewhat at odds with stereotypical views of autism. The children in the study expressed a strong desire to be part of the group and indicated friendships where this was the case. DHSC (Citation2014) note that children's perceptions of their well-being seem ‘most strongly influenced by relationships … with their peers’ (p. 1) and there are important links between self-esteem and peer relationships (Antonopoulou, Chaidemmenou, & Kouvava, Citation2019). Peer relationships featured heavily in all three child participants’ data, but this is not straightforward. The lack of emotional literacy and control that is associated with ASD and ADHD could impact the understanding of peer relationships (Goldsmith & Kelley, Citation2018). While research implies ASD can lead to a lack of friendships (Petrina et al., Citation2014), the raw data does not fully support this and therefore it is important to consider other possible reasons for the participants’ positive views of their relationships. A very grounded view is presented of what directly matters in the participants’ school day; this includes the environment they are in and what they take from it, the need to belong socially with peers and their sense of belonging within the school. Throughout all the themes, social inclusion is apparent. But what is not, is the recognition that adults who work closely with this group, don't appear to recognize the emerging social skills that the students are indicating. This raises the question of support. How can adults support the participants to develop these essential life skills without first listening to the views of those central to the discussion. For the child participants of this study, their sense of social belonging appears most influential to their well-being and yet budding skills are not recognized by those closest to them.

The participants’ main struggle was in the reciprocity of these relationships. Often, these participants recognized social expectations and signs. They were able to start to recognize positive social relationships in others when peers could provide this and how it helped their well-being while in school. Lai et al. (Citation2017, p. 690) recognizes that autistic children can mask their social difficulties through ‘learnt strategies’ (including overlearning social cues through observing others). This recognition of social relationships and actions to support positive friendships going forwards are important foundation skills which all three pupils demonstrated, yet oddly enough not recognized by staff and families. Without this recognition, it is possible that bespoke training and support won't be given by adults to target the development of these emerging well-being skills. This missed opportunity, only known by asking pupils directly, could mean they are not given the continued support needed. The question is what the best way is to do this is, and further conversations with the pupils are warranted. The question is what the best way is to do this is, and further conversations with the pupils are warranted.

Within the second theme recognizing safe spaces in school, all three participants identified spaces that they felt were ‘theirs’. The classroom is often seen as a collaborative space (Mulholland & O’Connor, Citation2016); however, all participants photographed or drew spaces which they felt was theirs and enjoyed individually, rather than the more public classroom spaces. The participants’ connection to their space could suggest a sense of identity linked to where they work in the classroom. Much of the language used in the comments about their individual spaces focuses on the usefulness of their workspace within a classwork context. However, another important note on the comments is an element of ownership and belonging by the repeated use of ‘my’ in all the participants (see ). Abdinasir (Citation2019) commented on how well-being can be linked with a sense of belonging, not only socially but belonging in their physical environment. Classrooms are often seen as space for the class as a whole and used to establish a feeling of belonging within it when the concept of ‘inclusion’ is considered (Mulholland & O’Connor, Citation2016). However, it is interesting how much of the raw data focused on their individual spaces. It could be that by having a designated area, these children can still feel part of the class group within the security of their own ‘safe space’. A common thread between the ‘when I feel safe … ’ drawings were the role of their peers at school in creating a safe space for them (see ). Despite being an individual space, the bridge providing opportunities for wider friendships was evident but largely unrecognized by adult support staff.

To the child participants, safety was represented in other ways too; within the feeling of belonging and their social relationships linked with being at school. Lisa connected the arrival to school with feeling safe, Andy recorded playing with friends, and Alice drew an art therapy session with her best friend. Consistent with the literature is the role of schools as being safe, nurturing environments for pupils in their care, and staff for providing provision to ‘support … (the) wellbeing of their pupils’ (DfE, Citation2021a, p. 42). What is interesting is that this literature largely focuses on safeguarding concerns (DfE, Citation2021a). However, none of the child participants referred to being protected from any dangers or the role of adults in helping them feel safe. Instead, the children's perspective of safety appears to come from their sense of belonging and friendships enhanced by having a designated area which they identify as their own.

It is interesting to note that each student could clearly identify the area or ways to help support their well-being. Whether this was a space or technique, they each could state what worked for them. Some of the examples cited were known and supported by the school (as part of the whole school ethos), but other aspects were not identified by adults. That very lack of awareness was given as a reason for participation in the study. However, it also shows the potential impact that underlying ‘invisible’ efforts can have, despite the pupils in the study not mentioning direct policies or day-to-day staff action. It could be argued that this is a positive outcome, to have externally noted good practice which is embedded in the school day to the point that children do not explicitly refer to it yet, but clearly enjoy the impact. The ‘hidden’ or ‘informal’ whole school culture to support student well-being can have a positive impact and is often recognized as best practice (DfE, Citation2018). What is less well known is the demonstrated impact this has on pupils. This research shows that pupils can see the positive change and recognize the importance of it, if only we ask them.

Limitations

It is important to note that this study is at a small scale and not representative of a complete understanding of student well-being. The sample size was identified through teacher referral so opportunistic; it was not systematic selection. However, it is important to note that while this sample size is small, it is not unusual of a typical classroom. Current research shows there is a prevalence of ASD diagnoses in the UK (Russell et al., Citation2022) and these three participants represent the SEND minority within an average primary school classroom. Recent research from the DfE (Citation2023, p. 10) has noted the increase ‘to 1.57 million pupils in 2023, representing 17.3% of all pupils’ with SEN. This shows the prevalence and need for schools to respond and support as is necessary.

Despite these limitations, the study's main contribution is to offer the use of innovative research tools, focused on being child-led and purposeful to capture their views. It aims for the voices of underrepresented autistic pupils in a class to be heard in an educational setting.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed well-being at the forefront of educational matters with the UK government focus on guiding schools to ‘support their pupils effectively’ (DfE, Citation2020a, para. 5). The timeliness of this project's focus, as well as the government's expectations on schools in terms of supporting student well-being, is therefore important and something all schools must consider.

Despite a small sample, a few cautious findings emerge from the study. Children's voices confirm the importance in listening to their views and this study demonstrates one innovative way to reach groups who are often overlooked or deemed as too hard to reach. Schools have a responsibility to provide an environment where all can thrive (DfE, Citation2020a) and part of determining this is by gaining an understanding of what pupils think, even those from hard-to-reach groups. The use of innovative tools, such as used in this research can help. Provision for student well-being should be informed by the views of all children including those hard-to-reach groups to show whether wider efforts are working. It is the responsibility of teaching staff to support student voice, particularly for SEN children who may not be able to express this as clearly as others. By considering how the children could share their views in new and innovative ways, staff play a key role in understanding, and ultimately improving, student well-being.

Awareness of well-being is an important life skill which creates a strong foundation leading to the development of social and educational skills. Although most would agree with the value of this focus, what seems less apparent is how adults recognize the efforts students make to practice the social skills necessary. If we don't ‘see’ the evidence, then it is more difficult to reinforce the activity. The sample students were able to share examples of times when they were tentatively developing friendships. The lack of this is often a key concern of families and these new skills are missed. It is only by starting the conversation and using alternative tools that schools can see if progress is being made through wider school strategies and individual support provided. This research has shown how this can be achieved in a mainstream setting.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the pupils for their insightful and helpful comments. Also, the authors wish to thank colleagues at the University of Reading for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, ER. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elena Rees

Elena Rees completed a PGCE at Institute of Education, University of Reading in 2017. While working as full time teacher in a primary school classroom, she completed a Masters degree in Education and graduated in 2022. This article features research she conducted during the writing of her dissertation which was awarded a distinction. Elena Rees continues to work full time in a primary school. She has keen interest in how educational staff can best support pupils with Special Education Needs and Disabilities and also in how schools can be centres for pupil wellbeing. She aims to go into educational leadership and is currently completing a National Professional Qualification in Senior Leadership at UCL.

Catherine Tissot

Professor Catherine Tissot is a member of staff at the Institute of Education, University of Reading. She has responsibility as University Teaching Fellow Community of Practice. She also is the Pathway leader for the Masters in Inclusive Education and leads the SENCO accreditation/qualification. Her areas of interest include special education theory and practice, Autistic spectrum disorders, inclusive education, international perspectives on inclusion and disability issues in general. She is involved in much enterprise activity, external roles and consultancy including trustee of a local school for autistic pupils and past governor at another SEND Autism-specialist school.

Notes

1 This article will use identity first language of ‘autistic pupil’, rather than ‘pupil with autism’ when referring to autistic participants, advocated in recent research (Botha, Hanlon, & Williams, Citation2021; Vivanti, Citation2020).

References

- Abdinasir, K. (2019). Making the grade: How education shapes young people’s mental health. Centre for Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-10/CentreforMH_CYPMHC_MakingTheGrade_PDF_1.pdf

- Alharahsheh, H., & Puius, A. (2020). A review of key paradigms: Positivism VS interpretivism. Global Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(3), 39–43. GAJHSS_23_39-43.pdf (gajrc.com)

- Amundsen, R., Riby, L. M., Hamilton, C., Hope, M., & McGann, D. (2020). Mindfulness in primary school children as a route to enhanced life satisfaction, positive outlook and effective emotion regulation. BMC Psychology, 8, 71. doi:10.1186/s40359-020-00428-y

- Anderson, D. L., & Graham, A. P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: Having a say at school. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(3), 348–366. doi:10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

- Antonopoulou, K., Chaidemmenou, A., & Kouvava, S. (2019). Peer acceptance and friendships among primary school pupils: Associations with loneliness, self-esteem and school engagement. Educational Psychology in Practice, 35(3), 339–351. doi:10.1080/02667363.2019.1604324

- Arnott, L., Martinez-Lejarreta, L., Wall, K., Blaisdell, C., & Palaiologou, I. (2020). Reflecting on three creative approaches to informed consent with children under six. British Educational Research Journal, 46(4), 786–810. doi:10.1002/berj.3619

- Arslan, G., & Coşkun, M. (2020). Student subjective wellbeing, school functioning, and psychological adjustment in high school adolescents: A latent variable analysis. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 4(2), 153–164. doi:10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.231

- Axford, N. (2009). Child well-being through different lenses: Why concept matters. Child & Family Social Work, 14(3), 372–383. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00611.x

- Bailey, J., & Baker, S. T. (2020). A synthesis of the quantitative literature on autistic pupils’ experience of barriers to inclusion in mainstream schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 20(4), 291–307. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12490

- Baldwin, D., Sinclair, J., & Simons, G. (2021). What is mental wellbeing? BJPsych Open, 7(S1), S236–S236. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.631

- Baron Cohen, S. (2001). Theory of mind in normal development and autism. Prisme, 34, 174–183.

- Benevides, T. W., Shore, S. M., Palmer, K., Duncan, P., Plank, A., Andresen, M.-L., … Coughlin, S. S. (2020). Listening to the autistic voice: Mental health priorities to guide research and practice in autism from stakeholder-driven project. Autism, 24(4), 822–833. doi:10.1177/1362361320908410

- Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & Williams, G. L. (2021). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to Vivanti. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20, 1–9. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

- Bourke, R. (2017). The ethics of including and ‘standing up’ for children and young people in educational research. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(3), 231–233. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1260823

- Bourne, P. A. (2010). A conceptual framework of wellbeing in some western nations (a review article). Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 2(1), 15–23.

- British Educational Research Association. (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research (4th ed.). London: BERA. Retrieved from https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Cibralic, S., Kohlhoff, J., Wallace, N., McMahon, C., & Eapen, V. (2019). A systematic review of emotional regulation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 68, Article 101422. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101422

- Danby, G., & Hamilton, P. (2016). Addressing the ‘elephant in the room’: The role of the primary school practitioner in supporting children’s mental well-being. Pastoral Care in Education, 34(2), 90–103. doi:10.1080/02643944.2016.1167110

- Department for Education. (2010, August 15). Childhood wellbeing: A brief overview (Wellbeing-Brief). GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-wellbeing-a-brief-overview

- Department for Education. (2018). Mental health and behaviour in schools (DfE-00327-2018). GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mental-health-and-behaviour-in-schools–2

- Department for Education. (2020a). State of the nation 2020: Children and young people’s wellbeing (DFE-RR-999). GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/state-of-the-nation-2020-children-and-young-peoples-wellbeing

- Department for Education. (2021a). Senior mental health lead training. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/senior-mental-health-lead-training

- Department for Education. (2022). State of the Nation 2021: Children and young people’s wellbeing research report. GOV.UK Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1053302/State_of_the_Nation_CYP_Wellbeing_2022.pdf

- Department for Education. (2023). Special educational needs and disability: An analysis and summary of data sources. June 2023. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sen-analysis-and-summary-of-data-sources

- Department of Health and Social Care. (2014). Wellbeing and health policy. GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wellbeing-and-health-policy

- Department of Health and Social Care & Department for Education. (2015). SEND code of practice: 0 to 25 years (DFE-00205-2013). GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25

- Department of Health and Social Care & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper (Cm.9626). GOV.UK. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/transforming-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-provision-a-green-paper

- Dockett, S., Perry, B., & Kearney, E. (2013). Promoting children’s informed assent in research participation. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(7), 802–828. doi:10.1080/09518398.2012.666289

- Drew, H., & Banerjee, R. (2019). Supporting the education and wellbeing of children who are looked-after: What is the role of the virtual school? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34, 101–121. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0374-0

- Einarsdottir, J., Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (2009). Making meaning: Children’s perspectives expressed through drawings. Early Child Development and Care, 179(2), 217–232. doi:10.1080/03004430802666999

- Elliott, V. (2018). Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. The Qualitative Report, 23(11), 2850–2861. Retrieved from https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss11/14

- Facca, D., Gladstone, B., & Teachman, G. (2020). Working the limits of ‘giving voice’ to children: A critical conceptual review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, Article 160940692093339. doi:10.1177/1609406920933391

- Foley, C. (2015). Girls, mathematics and identity: Creative approaches to gaining a girls’-eye view. In G. Adams, (Ed.), Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics, 35(3), 1–6. Retrieved from http://www.bsrlm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/BSRLM-IP-35-3-08.pdf

- Goldsmith, S. F., & Kelley, E. (2018). Associations between emotion regulation and social impairment in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 2164–2173. doi:10.1007/s10803-018-3483-3

- Griffin, J., & Gore, N. (2023). ‘Different things at different times’: Wellbeing strategies and processes identified by parents of children who have an intellectual disability or who are autistic, or both. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 36(4), 822–829. doi:10.1111/jar.13098

- Hale, C. M. (2004). Social communication in children with autism: The role of theory of mind in discourse development linguistics and language behavior abstracts (LLBA). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/social-communication-children-with-autism-role/docview/85610800/se-2?accountid=13460

- Kansky, J., & Diener, E. (2017). Benefits of wellbeing: Health, social relationships, work, and resilience. Journal of Positive Psychology and Wellbeing, 1(2), 129–169.

- Kirby, P. (2020). ‘It’s never ok to say no to teachers’: Children’s research consent and dissent in conforming schools contexts. British Educational Research Journal, 46(4), 811–828. doi:10.1002/berj.3638

- Konu, A., & Rimpela, M. (2002). Well-being in schools: A conceptual model. Health Promotion International, 17, 79–87. doi:10.1093/heapro/17.1.79

- Kyriacou, C. (2012). Children’s social and emotional wellbeing in schools: A critical perspective. By D. Watson, C. Emery and P. Bayliss with M. Boushel and K. McInnes. British Journal of Educational Studies, 60(4), 439–441. doi:10.1080/00071005.2012.742274

- Lai, M.-C., Lombardo, M. V., Ruigrok, A. N. V., Chakrabarti, B., Auyeung, B., Szatmari, P., Happe, F., & Baron-Cohen; MRC AIMS Consortium. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism, 21(6), 690–702. doi:10.1177/1362361316671012

- Lloyd, K., & Emerson, L. (2017). (Re)examining the relationship between children’s subjective wellbeing and their perceptions of participation rights. Child Indicators Research, 10, 591–608. doi:10.1007/s12187-016-9396-9

- Marquez, J., & Main, G. (2021). Can schools and education policy make children happier? A comparative study in 33 countries. Child Indicators Research, 14, 283–339. doi:10.1007/s12187-020-09758-0

- McDonough, A., & Sullivan, P. (2014). Seeking insights into young children’s beliefs about mathematics and learning. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 87, 279–296. doi:10.1007/s10649-014-9565-z

- Mulholland, M., & O’Connor, U. (2016). Collaborative classroom practice for inclusion: Perspectives of classroom teachers and learning support/resource teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1070–1083. doi:10.1080/13603116.2016.1145266

- National Association of Headteachers (NAHT). (2020, February 3). Huge rise in number of school-based counsellors over past three years. www.naht.org.ukhttps://www.place2be.org.uk/media/rnuf5drw/place2be-and-naht-research-results.pdf. Retrieved from www.naht.org.ukhttps://www.place2be.org.uk/media/rnuf5drw/place2be-and-naht-research-results.pdf

- National Autistic Society. (2021). School report. Retrieved from https://s2.chorus-mk.thirdlight.com/file/24/0HTGORW0HHJnx_c0HLZm0HWvpWc/NAS-Education-Report-2021-A420281%29.pdf

- NHS Digital. (2019). Waiting times for children and young people’s mental health services, 2018-2019. Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/find-data-and-publications/supplementary-information/2019-supplementary-information-files/waiting-times-for-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-services-2018—2019-additional-statistics

- NHS Digital. (2020). Waiting times for children and young people’s mental health services, 2019–2020. Retrieved from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/supplementary-information/2020/waiting-times-for-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-services-2019—2020-additional-statistics

- Pegues, H. (2007). Of paradigm wars: Constructivism, objectivism and postmodern stratagem. The Educational Forum, 71(4), 316–330. doi:10.1080/00131720709335022

- Petrina, N., Carter, M., & Stephenson, J. (2014). The nature of friendship in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(2), 111–126. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.016

- Powney, J., & Watts, M. (2018). Interviewing in educational research. London: Routledge. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nLReDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT9&dq=interviews+educational+research&ots=OSUO3NNNri&sig=JTyREOl7O2znCIVOH4Cqak7YaBs#v=onepage&q=interviews%20educational%20research&f=false

- Redquest, B. K., Stewart, S. L., Bryden, P. J., & Fletcher, P. C. (2020). Assessing the wellbeing of individuals with autism using the interRAI child and youth mental health (ChYMH) and the interRAI child and youth mental health – developmental disabilities (ChYMH-DD) tools. Pediatric Nursing, 46(2), 83–91.

- Russell, G., Stapley, S., Newlove-Delgado, T., Salmon, A., White, R., Warren, F., … Ford, T. (2022). Time trends in autism diagnosis over 20 years: A UK population-based cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(6), 674–682. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13505

- Tierney, S., Burns, J., & Kilbey, E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: Social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 73–83. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.013

- Tobia, V., Greco, A., Steca, P., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2019). Children’s wellbeing at school: A multi-dimensional and multi-informant approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 841–861. doi:10.1007/s10902-018-9974-2

- UNICEF. (1989, November 20). The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child-uncrc.pdf=

- Vivanti, G. (2020). Ask the editor: What is the most appropriate Way to talk about individuals with a diagnosis of autism? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 691–693. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-04280-x

- Wager, E., & Kleinert, S. (2011). Responsible research publication: International standards for authors. A position statement developed at the 2nd world conference on research integrity, Singapore, July 22–24, 2010. Chapter 50. In T. Mayer & N. Steneck (Eds.), Promoting research integrity in a global environment (pp. 309–316). Singapore: Imperial College Press / World Scientific Publishing.