ABSTRACT

In recent years, a growing amount of attention has been paid to the jazz diaspora within specific historical, social, and political contexts. Nevertheless, activities that took place outside of capital cities are often ignored, despite many local scenes within their own larger diasporic environment playing a significant role in the development of jazz – and Portugal is a case in point. In Porto, an urban center in northern Portugal, in the late 1950s, in the context of the New State regime under Dr. Oliveira Salazar, a group of jazz enthusiasts created a space in which this music could be listened to, discussed, and celebrated. This space could be described as a kind of “DIY” jazz club and was notable for disseminating the genre across the region. However, as with so many diasporic locations, Portugal’s historical accounts of its jazz heritage, both local and national, largely fail to acknowledge activity outside the nation’s capital. This essay examines the inception of the Porto jazz scene in the post-World War II period and focuses on the connections between the local, the national, and the global.

Introduction

Recent decades have seen growing attention being paid to the development of jazz across the globe (CitationBallantine; CitationAtkins, Blue Nippon and Jazz Planet; CitationBohlman and Plastino).Footnote1 As Bruce Johnson observes, “jazz was not ‘invented’ and then exported. It was invented in the process of being disseminated” (“CitationJohnson” 39). Pioneering works focusing on the jazz diaspora have inspired a new generation of researchers who are now conscious of the limitations inherent in understanding the development of this music through a focus on a single country–e.g. the United States–whether it be geographically or through its artists (CitationJohnson, Jazz Diaspora). An ongoing issue is that the history of jazz has predominantly been framed as the history of recorded jazz (CitationRasula; CitationMyers). Besides this, any consideration of the European context to date would most likely be an examination of the careers of African-American artists, either those settled in Europe or touring the continent. Furthermore, those narratives have largely privileged those artists based in central or northern European countries. Such an oversimplification has created assumptions about jazz as a social and musical practice in other diasporic locations – southern European countries, for example (CitationFox; CitationStraka). However, this state of affairs is starting to change.Footnote2 Stories from outside the capital cities remain conspicuous by their absence, however, despite these locations’ crucial role in developing jazz in many diasporic environments, Portugal being one such case.Footnote3

This essay analyzes the development of Porto’s jazz scene post-World War II, and is divided into three parts. The first, “The Context,” begins by briefly contextualizing the Portuguese New State regime in the late 1930s and the strong opposition from Portuguese Catholic Action (Acção Católica Portuguesa) to contemporary dance fashions, especially those related to jazz. The second part, “The Birth of Porto’s Jazz Scene,” is organized into three sections exploring jazz-related events in the city. “Jazz Bands, Foreign Visitors, and Detractors” provides a brief outline of the early presence of jazz (or what was perceived as jazz) in Porto, some foreign artists, the significance of cinema in disseminating jazz locally, and the prejudice encountered by local jazz bands. “Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães and the Hot Club Connection” highlights the contacts made between Porto jazz enthusiast Brito Guimarães and Lisbon-based jazz promoter Luis Villas-Boas; it addresses in particular their exchange of correspondence between 1946 and 1956. Lastly in this second part, “The Inception of a ‘DIY’ Jazz Club in Porto” examines the activities in the city that led to the creation of a local jazz club. The third part, “Secção de Jazz do Clube Fenianos Portuense,” describes what I identify as Porto’s first jazz club, during the late 1950s.Footnote4 This section is based on archival and bibliographical research and discusses original documentation related to the Porto scene of the late 1950s and its spaces and networks. Although accounts of Porto’s contemporary jazz scene are available, especially relating to twenty-first-century activity and around the Porta-Jazz association, no detailed analysis of the earlier period has yet been published.Footnote5 To go back in time and examine the inception of Porto’s jazz scene in the post-World War II period, I will be relying on historical documentation in personal collections and institutional archives and on recollections and experiences of interviewees.

This research is also informed by my personal experience as someone who grew up and lived in Porto for almost four decades–firstly as a music student and later as a musician, educator, and emerging researcher. However, I was not a direct participant in the jazz scene examined in this article and have no direct experience of the culture of the late 1940s, or the 1950s or 1960s. I was, however, part of Porto’s music scene during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s and 2000s and visited many of the places and venues under investigation, including some that are no longer active. I also met and talked with some of the individuals involved in Porto’s scene in the period examined. I must therefore also consider my involvement and participation in the local scene as an insider/outsider.

The Context: The New State Regime

Edward CitationSaid alerted us to the fact that music should not be understood simply as a reflection of society, but rather as “an ensemble of political and social involvements, affirmations, transgressions, none of which is easily reducible either to simple apartness or to a reflection of coarse reality” (71). Therefore, the inception of Porto’s jazz scene must be framed within a specific social, cultural, and political context, namely the New State regime under the governance of Dr. Oliveira Salazar (1933–1968), Europe’s longest-serving right-wing dictator.Footnote6

From 1933 until April 1974, the New State regime – an authoritarian, right-wing, conservative, colonialist project, with a Catholic-rooted vision of politics and society – its main slogan being “Deus, Pátria e Família” (“God, Homeland and Family”) – ruled Portugal.Footnote7 During this period, known as Salazarism, nationalist cultural symbols were widely circulated, and the colonial mentality was amplified in ways to legitimize authoritarian power both in domestic and foreign policy, sustained by the guiding slogan “Tudo pela Nação, nada contra a Nação” (“All for the nation, nothing against the nation”). These nationalist discourses, combined with a dominant colonial ideology in power, threatened the acceptability of new forms of entertainment from abroad, such as jazz, which was strongly associated with its African origins. Being an imported cultural phenomenon, the genre was soon at odds with the regime’s conservative nationalist values, and it was perceived as a moral threat to rural areas (CitationMelo).

With Catholic conservative values and morality dominant in the country, jazz encountered strong opposition from the Portuguese Catholic Church (CitationCravinho, “Historical”). As analyzed elsewhere, from March 1938 onwards Dr. Molho de Faria, on behalf of Acção Católica Portuguesa (Portuguese Catholic Action), launched a crusade against modern dances and jazz, proclaiming the latter’s repugnancy by dint of its African origins and associations with Blackness.Footnote8 A key plank of Faria’s argument was that close contact between the sexes while jazz dancing could lead to venereal diseases and that dancing, playing, or watching jazz bands could cause female infertility (CitationFaria, “Os Bailes”). The Portuguese Catholic Church was a crucial pillar of the New State regime, so, ludicrous as this moral panic sounds to modern ears, many sensed a genuine threat to Portuguese society and Portuguese womenfolk.

During World War II, Portugal’s neutrality allowed both Nazi and Allied agents to operate with impunity, albeit under the intense surveillance of the Portuguese Political Police (CitationCravinho, Encounters). They were joined in Lisbon by thousands of refugees, which included many Jewish families looking for safe passage to the United States. Just outside Lisbon, the Portuguese Riviera, or Costa do Sol, became the new home for members of European royal families in search of a safe location to relax and to pursue their customary party-going and gambling routines, for example in the Casino do Estoril. As the conflict progressed and the United States became involved, the Estado Novo regime made a symbolic approach toward the Allied forces, even though Salazar maintained his distrust of the United States’s liberal values. Both governments, however, shared a common enemy: the Soviet Union and communism. These developments precipitated a craze for jazz and swing, particularly within the main urban centers, supported by the U.S. Embassy in Lisbon, which persisted throughout the 1950s and 1960s. However, this was largely the preserve of urban elites, who were allowed some autonomy in entertainment and nightlife, which was not the case for the rest of the population, i.e. o povo (“the people”).

Consequently, jazz (and modern dances) emerged as a kind of “in-between” music, a sonic element breaching the dichotomy of dominant cultural practices of different social strata within Portuguese society. On the one hand, this culture was sanctioned as legitimate entertainment in nightclubs and casinos in the main urban centers and coastal areas, and at the parties of the bourgeois elite; the universities and their students also fell into this category (CitationCravinho, “The “Truth”“ and Essays). On the other hand, in state-supported cultural institutions like the Casas do Povo (“People’s houses”), which were established by the New State regime in rural areas, the practice of this dangerous culture, a threat to rural traditions, was controlled or even proscribed (CitationMelo).

Nevertheless, the urban areas also saw resistance and opposition from conservative elements, largely because jazz was seen as foreign, a music with African origins, associated with African Americans and a threat to dominant Portuguese conservative nationalist and colonialist values. For example, a request was sent by the president of the Federação das Sociedades de Educação e Recreio (“Federation of Education and Recreation Societies”), M. Vaz Pereira, on 8 December 1942, to Lisbon’s Civil Governor requesting the “prohibition of the practice of ‘SUWNG’ [sic] in recreational communities.”Footnote9 According to Vaz Pereira, this “American dance called ‘SUWNG’ [sic] which, due to its fast-paced and exhausting rhythm as well as the way it is performed and the exaggeration of the positions [of its practitioners], brings unpleasant consequences.”Footnote10 It had a bad effect on practitioners’ “morale,” causing “lack of composure.”Footnote11 On December 14, according to the document’s handwritten notes, the Civil Governor of Lisbon wrote the following: “I don’t have the capacity to appreciate the nature, appearance and consequences of the dance to which this office refers,” adding that it was the responsibility of dance societies “to direct and guide their parties in the way most appropriate for morale and hygiene.”Footnote12

Although this exchange took place in Lisbon, not Porto, it is illustrative of attitudes in Portugal generally, where distaste for jazz was based on a perceived threat to conservative values and strongly driven by Catholic morality. It also reveals the lack of clarity about who was responsible for the supervision and regulation of recreational societies. During my fieldwork in Porto, I heard anecdotal reports of similar instances occurring in that city (e.g. the establishment of a jazz club in Porto in the late 1940s was blocked because it was seen by the local authorities as “Negro” music), but no official documentation was to be found.Footnote13

The Birth of Porto’s Jazz Scene

Since CitationHobsbawm examined the intersection of jazz practice and popular culture in his 1960 work The Jazz Scene, the term “scene” has been used frequently in music research to refer to or represent smaller subsets within society associated with genres and subgenres (see, e.g. CitationBryant et al.; CitationStewart; CitationJackson; CitationJago). And, since CitationStraw‘s “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music,” academics have begun to explore the term “scene” within “jazz worlds” (to use an analogy with CitationBecker‘s term). More recently, another significant contribution was made by CitationPeterson and Bennett to the understanding of the complexity of the term “scene,” whereby they suggested a typology consisting of three major divisions: local, translocal, and virtual. The first category, local scenes, includes those that tend to represent “long-standing local cultures” and focus on “the relationship between the local music-making process and the everyday life of specific communities” (7). “Translocal” describes those local scenes that are “in regular contact with similar scenes in distant places interacting with each other through the exchange of recordings, bands, fans and fanzines” (8). In the third category, the virtual scene, participants are widely separated geographically but linked through a “single scene-making conversation via the Internet” (9). Informed by these debates, this article explores the inception of Porto’s jazz scene in the post-World War II period, highlighting its spaces, networks, and local and global connections. It aims to further the understanding of Portuguese jazz culture under the New State regime.

Jazz Bands, Foreign Visitors, and Detractors

As mentioned elsewhere, jazz (or what was perceived as jazz) as a new musical and social practice had been performed in Porto since the early 1920s, with jazz bands appearing in local theaters, hotels, and nightclubs (CitationCravinho, “Historical”). On 4 February 1923, the daily newspaper O Primeiro de Janeiro announced an event at the Teatro Carlos Alberto: “For the 1st time in Porto an authentic jazz band.”Footnote14 A detailed analysis of local daily newspapers from that period reveals the increasing presence of jazz bands in venues across the city (CitationCravinho, Encounters).Footnote15 The culture was adopted by the 1930s Porto bourgeois elites, and local jazz bands would feature at parties and dinners in hotels and as attractions at the launches of new clubs, such as the Club do Porto in Rua Formosa no. 112.

On 11 January 1928, the Black theatrical company run by Louis Douglas – Black Follies – visited Portugal, and their show La Revue Négre premiered in Porto.Footnote16 After several days in Lisbon, the Douglas company traveled to north Portugal for three shows. The forty African-American artists (musicians and dancers) at the Teatro Sá da Bandeira were received with enthusiasm by the public and local press, who gave accounts of the exotic dances and music (CitationCravinho, “Historical”). Among those African-American artists was a certain Sidney Bechet, although at that time largely unknown to the Portuguese public.Footnote17

A significant contributor to the dissemination of jazz in Porto’s public sphere was the cinema. In mid-April 1931, the Primeiro de Janeiro announced the premiere of the movie Princesa do Jazz (The Jazz Princess), aka Street Girl – directed by Wesley Ruggles and starring Betty Compson, John Harron, and Jack Oakie – at the Cinema Águia d’Ouro.Footnote18 On 5 May 1931, the same local newspaper announced another premiere: Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra’s movie O Rei do Jazz (King of Jazz) at the Cinema Trindade.Footnote19 Cinema had a big part to play in the visual representation of jazz for those who might otherwise have had no experience of the genre.

In the way of live performances, in April 1935 a female jazz band was seen in Porto: the Blue Jazz Ladies, led by Leon Selinsky and featuring Cris Flek, Juan Maas, Else Koehler, Kathe Daumichen, Pole Ingel, Ilse Anders, Nelly Kuipers, Dora Burow Leib, Franciska Schotter Abas, and Elly Marel (all women, bar the first two listed; see below). Billed as “the most famous Orquestra Feminina Blues Jazz Ladies,” they had debuted at the Lisbon nightclub Maxim’s on March 30. However, the New State regime’s relationship with the Soviet Union was not favorable, and the two Russian band members were prohibited from entering the country, as noted by Selinsky in a contemporary interview:

I had to replace two of them with men because they are Russian and not allowed to enter Portugal. I must say that I am incredibly grateful for the kind cooperation I had from Customs and Lisbon’s International [Political] Police [PIDE].Footnote20

According to the Portuguese press, after a three-week stint at Maxim’s, the Blue Jazz Ladies traveled to Porto to perform at the Salão de Automobilismo e de Aviação Civil (Motoring and Civil Aviation Show) before leaving the country.

However, there is a general lack of documentation about Porto’s jazz musicians from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.Footnote21 What have survived are commentaries in the press – both positive and negative – about those performances (CitationCravinho, “Historical”). For example, Portuguese folklorist Armando CitationLeça had a regular section in the Arte Musical magazine, entitled “Da Caninha Verde à Sonata” (“From Caninha Verde to Sonata”),Footnote22 in which he decried the presence of a jazz band at Porto’s Café Guarani, describing its music as primitive, without beat or tonal stability, and resembling the sounds of the jungle.

Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães and the Hot Club Connection

In the early postwar years, a group of Porto jazz enthusiasts began to coalesce, inspired by Luís Villas-Boas’s radio program Hot Club and his tireless efforts to establish the Hot Clube de Portugal (Hot Club of Portugal [HCP]) (CitationCravinho, “Portugal”). However, Porto jazz aficionado Joaquim de Macedo’s attempt, in early 1946, to found the Hot Clube do Porto (Hot Club of Porto) met without success.Footnote23 But there was another important figure in that period: Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães. An active supporter of Villas-Boas’s crusade to disseminate jazz in Lisbon, Brito Guimarães would become a leading figure on the Porto scene over the following decades.

In the early 1950s, Porto enthusiasts maintained a connection with jazz developments worldwide by subscribing to foreign jazz magazines such as France’s Jazz Hot and America’s Down Beat. Porto promoters and fans kept their fingers on the pulse of contemporary discourses and received regular bulletins about album releases on the other side of the Atlantic and about African-American artists’ European tours. The twenty-one-year-old Porto radio disc jockey José Luiz CitationNobre was published in Down Beat, in a short piece entitled “On Oporto Air,” in which he observed that Down Beat was the “best magazine of its kind, with good news, good photos and very well printed. It gives me interesting subjects for my weekly program on the wireless.” He also expressed a wish “to correspond with someone interested in vocal jazz.” We see from this example that Porto jazz enthusiasts not only aspired to connect to their peers across the Atlantic but also perceived themselves as part of a larger “imagined” international jazz community (CitationAnderson). This could be interpreted as a precursor to CitationPeterson and Bennett‘s “virtual scenes.” Like many other diasporic locations, Porto’s jazz culture existed at “the intersection between global flows of media and local cultural expression[s]” (CitationJago 30).

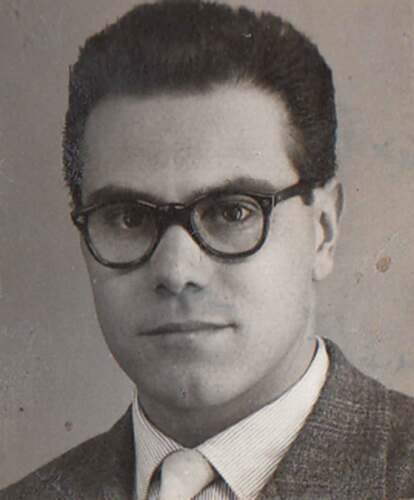

The exchange of correspondence between Villas-Boas and Brito Guimarães allows us to examine the growing friendship between these two enthusiasts and to see how a connection plays out between scenes in different parts of the country. Luís Villas-Boas was a Lisbon-born jazz aficionado and a leading figure of the second half of the twentieth century in the dissemination of jazz in the metropolitan area of Lisbon and beyond (CitationSantos). Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães () was a Porto-born jazz aficionado and amateur trumpeter who was based in Coimbra during his academic training and was responsible for a number of jazz-related activities in central and northern Portugal. While Luís Villas-Boas’s work has been widely acknowledged, Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães remains largely unknown, even at a local level.Footnote24

The Inception of a “DIY” Jazz Club in Porto

The correspondence between Villas-Boas and Brito Guimarães gives us an insight into, among other things, the concerns of Portuguese jazz promoters at the time and into local intrigues. For example, there was a dispute between Joaquim Macedo and Brito Guimarães over who was to be the official representative of the Hot Clube de Portugal in Porto. Luís Villas-Boas, who was in regular contact with both, always maintained a neutral position, encouraging cooperation between the two Porto promoters toward the general benefit of the dissemination of jazz in northern Portugal.Footnote25 The correspondence between them also reveals the extensive network of contacts that Villas-Boas shared with Brito Guimarães – both in the Iberian Peninsula (Madrid and Barcelona) and France (Paris).Footnote26 A persistent problem on the domestic front was Villas-Boas’s difficulty in purchasing jazz albums for his Lisbon radio program. Porto’s city-center store, O Grande Bazar do Porto (Grand Bazaar of Porto), located in Rua Santa Catarina and a destination for local jazz fans, actually stocked many of the discs Villas-Boas was looking for.Footnote27 Brito Guimarães consequently became a supplier of books and records for the Lisbon Hot Club radio show.Footnote28

Brito Guimarães had been a supporter of Villas-Boas’s crusade to establish the Hot Club of Portugal, as a result of which, in early April 1956, the former was appointed as the Hot Club’s first “correspondent” member.Footnote29 Their surviving correspondence is also a testament to the challenges that confronted Luís Villas-Boas in those days: in founding the first ever jazz club in Portugal, in organizing jam sessions, in making contact with foreign artists, and in leading the Hot Club’s early activities. This period, it should be noted, was a crucial one for the development of jazz in Lisbon, with Luis Villas-Boas and the Hot Club putting on the country’s first jazz festivals (CitationCravinho, “Portugal”).

The first took place in Lisbon at the Cinema Condes on 27 July 1953, and went by the name of “1° Festival de Música Moderna” (“First Modern Music Festival”). The following year, the HCP under Villas-Boas organized a second jazz festival in Lisbon, which took place on 5 April 1954, at the Cinema Capitólio and was also billed as a “modern music” festival. A third – still under the “modern music” banner, the “3° Festival de Música Moderna” – also organized by Villas-Boas, took place on 25 July 1955, again at Lisbon’s Cinema Condes. In these latter two, in addition to the performances, jazz-related movies and documentaries were presented. A fourth festival took place on 3 November 1958, at the Cinema Roma, also organized by the HCP, but this time named the “4° Festival de Música de Jazz” (Fourth Jazz Festival) and featuring both Portuguese and foreign professionals who performed regularly in the nightclubs of Lisbon. During the late 1950s, Lisbon fans witnessed an increase in the circulation of foreign jazz artists in the city, which sometimes also extended to Coimbra (CitationCravinho, “Portugal”). However, Porto was not yet part of that circuit, a situation that would only begin to change in the following decade, when both Lisbon-based and international jazz musicians appeared regularly in the city.

On 28 March 1957, the local newspaper Diário do Norte, under the title “História do Jazz” (“Jazz History”), announced: “launching a series of cultural activities on the theme of modernity, the first session of jazz music will be held today in Fenianos.”Footnote30 The venue chosen was the Clube Fenianos Portuenses (CFP), a nonprofit cultural and recreational association with public-utility status and operating under the motto “Pelo Porto” (“For Porto”). The CFP, located next to Porto City Hall, regularly hosted cultural and musical events.Footnote31 Earlier that year, in late January, an internal circular from the CFP Comissão de Festas (Party Committee) had invited its members to a “soirée dançante” (evening ball) on Saturday, February 2, at 10:00 p.m., featuring the Freitas Morna Orchestra.Footnote32

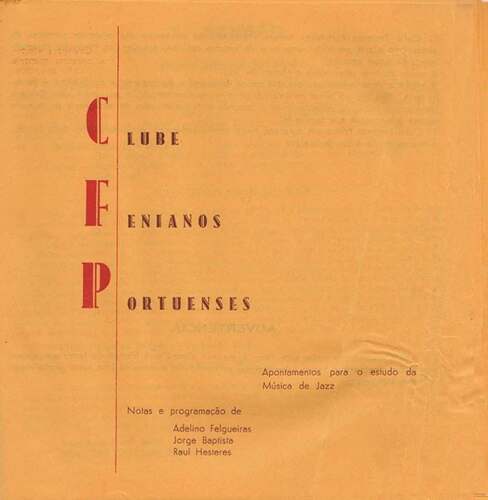

Although music was usually heard at many CFP events and parties, this was the first jazz phonographic session to be held at the club (see ). We are privy to the Porto jazz promoters’ playlists, records, and notes from these sessions: Artists included the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band, Big Bill Broonzy, Bessie Smith, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, Sidney Bechet, Fats Waller, and Coleman Hawkins. The list shows the predominance of U.S. source materials in Porto’s jazz scene at the time. Of all these artists, only one had visited Portugal, and that was Sidney Bechet (CitationCravinho, “The ‘Truth’ of Jazz”).

Figure 2. The program of the first Fenianos jazz sessions, 1957. Courtesy of the Clube Fenianos Portuense.

The second session took place on April 4, as announced in the Diário do Norte: “A session of jazz music in Fenianos. Continuing a series of cultural activities, the second session of jazz music will be held tomorrow at 9:30 pm at Clube Fenianos Portuenses under the guidance of Adelino Felgueiras, Jorge Baptista, and Raul Testor Hestnos.”Footnote33 During these sessions, the Porto promoters also held book discussions, mainly about English or French titles, such as Encyclopedia of Jazz (Leonard Feather), Jazz (Rex Harris), Histoire du Jazz (Barry Ulanov), La Véritable Musique du Jazz (Hugues Panassié), and the Dictionary of Jazz (Hugues Panassié and Madeleine Gautier) – an insight into what publications were available to local enthusiasts at the time. Being foreign-language resources, these texts were not accessible to all and remained the preserve largely of university students and other educated individuals. The first translations into Portuguese were done by the Lisbon-based jazz critic Raul Calado and appeared a few years later: Jazz (CitationRex Harris) and História do Verdadeiro Jazz (Hugues CitationPanassié).

The second phonographic session featured music from Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, Roy Eldridge, Lester Young and Oscar Peterson, Gerry Mulligan, and Dave Brubeck and some tracks from Louis Armstrong’s album dedicated to W. C. Handy. We can infer from this the continuation of strong U.S. influence on the scene. Of the artists who featured in the second phonographic session, only the Count Basie Orchestra and jazz singer Joe Williams had played in Portugal, performing in Lisbon at the Cinema Império on 1 October 1956 (CitationCravinho, “Portugal”). Nevertheless, Porto enthusiasts were able to access the latest albums released by many North American artists, which marks it as a “translocal scene” in CitationPeterson and Bennett‘s typology.

A third jazz phonographic session took place at the Fenianos in late April 1957, this time led by three other promoters: “CLUBE FENIANOS PORTUENSES … Continuing the work of cultural dissemination initiated with interest in the particular field of jazz music, the third session will be held tomorrow at 9:30 pm, with Dr. Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães, Manuel Begonha Perry Câmara, and António Nobre.”Footnote34 As regards performing musicians at that time, there were some professionals working on the Porto scene in nightclubs, as well as a few amateurs, mostly university students, involved in informal jazz sessions. However, no recordings of those sessions have ever emerged. Nonetheless, the surviving evidence of the CFP phonographic sessions reveals an informal network of social interactions among young enthusiasts across the city, promoting discussion and exchange of ideas. At the time in Portugal, depending on the context, “jazz (listening to it as well playing it) was an act of resistance” (CitationPaes 470).Footnote35

During this period, jazz spoke broadly to those university communities that opposed the New State regime, as was the case with some members of Lisbon’s Clube Universitário de Jazz (University Jazz Club; CUJ), led by Raul Calado (CitationCravinho, “The ‘Truth’ of Jazz”). Their phonographic sessions subliminally conveyed subversive messages, addressing the relationship between jazz, African-American communities, and the Civil Rights Movement, implicitly linking those foreign issues to Portugal and its African colonies, specifically Salazar’s colonial policies (CitationCravinho, “A Kind of “In-Between”“). However, it has not been possible, either by means of interviews or surviving documentation in institutional archives and private collections, to identify similar subversive initiatives by the CFP in their sessions.

Secção de Jazz Do Clube Fenianos Portuense

These activities in Porto finally led to the creation of the Secção de Jazz (“Jazz Section” [SJ-CFP]), which is most likely Porto’s first ever jazz club. It was founded as one of the cultural sections of the Clube Fenianos Portuense, during an ordinary general meeting that took place on 3 July 1957, chaired by Jaime Vilhena de Andrade:

Jazz Music Section: As a result of an artistic activity promoted by our partner, Mr. Hélder Veiga Pires, and undertaken by a group of jazz music fans, and which aroused interest, attracting an appreciable number of young people, it was decided to accept the formation of this Section at the request of a component of that Group … with the Chief Executive Officer being Mr. Dário Ramos Júnior.Footnote36

An important point is that, at the time, any new member benefited from a waiver of their registration fee.Footnote37 Consequently, the creation of the Jazz Section “brought the club many new members,” as reported in the minutes of the CFP General Assembly held on 11 December 1957.Footnote38 It was in some ways an autonomous “DIY” jazz club within the CFP structure, alongside other cultural sections, like “Juventude” (Youth), “Xadrez” (Chess), “Damas” (Checkers), and “Teatro” (Theater). Although its members were mainly jazz fans, some SJ-CFP members also participated in other local cultural associations, such as Cineclube do Porto (Porto Cinema Club), Teatro Experimental do Porto (Porto Experimental Theater), and Ateneu Comercial do Porto (Porto Business Atheneum). Since December 1955, the Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto (Porto Symphony Orchestra) had been headquartered at the CFP, not least because the CFP was a two-hundred-capacity venue,Footnote39 and hence the CFP put on classical concerts and sessions. SJ-CFP members could clearly benefit from a broad range of cultural and musical activities.Footnote40

In the accounting report for 1957, the CFP Board communicated the following to its members:

JAZZ SECTION

Another Cultural Section was created, the merits of which were put to the test in the undertaking of certain goals, which attracted a number of people to the Club who are interested in disseminating an understanding of certain types of jazz music. Led by a group of experts and artists who are well known in the music world, its activity is worthy of support. We sincerely hope that the Section’s leaders are able to continue the work that they have begun – as it turns out, under good auspices – and pursue the cultural responsibilities they have taken on with such dedication.Footnote41

The Jazz Section exerted a profound influence on the dissemination of jazz locally. Musical instruments were bought.Footnote42 It was a social space dedicated to jazz within an important cultural hub in the heart of Porto, boasting a hundred members by late 1958.Footnote43 As well as regular phonographic sessions, the SJF also organized other cultural activities, such as jazz film sessions and concerts featuring local amateur musicians.Footnote44

The SJ-CFP member profiles provide an outline of the late-1950s Porto scene – but one thing is immediately noticeable on the membership forms: Brito Guimarães and Manuel Nobre proposed the majority of the members.Footnote45 Also apparent is the gender inequality and male hegemony: Out of one hundred members there is only one woman, Maria Celina de Freitas Moreira. This is in fact comparable to the Lisbon and Coimbra scenes at the time.Footnote46 The context for this is a regime that, under the slogan “A Mulher para o Lar” (“Woman for the Home”), sought to confine women to domestic roles by means of mechanisms of social control (CitationNeves and Calado) – which in significant part consisted of jurisdiction over the body and sexual morality. Severe measures were imposed to impede and condition women workers, sometimes prohibiting access to specific professions or preventing marriage in others (CitationVaquinhas). Prohibitions also included travel without marital authorization. This hostile environment, enforced under the yoke of the Portuguese Catholic Church’s conservative and normative values about gender roles, goes a long way to explain the absence of women in Portuguese jazz scenes. This absence persisted even after the overthrow of the New State regime.

As to ethnicity, it was an almost exclusively Portuguese white male scene, with only one exception: a man of German descent. Regarding age distribution, the young-adult demographic is prominent, with an average age of twenty-five. Only one member was over forty, and nine (less than ten per cent) under twenty. As to residency, most members (ninety-eight per cent) lived in the city center, which implies a robust urban culture. Only two members lived elsewhere–one on the outskirts, in Matosinhos, and the other in another city south of Porto, Estarreja. The latter was a University of Porto alumnus working as an engineer in the Fábrica de Amoníaco Português (Portuguese Ammonia Factory) in Estarreja.

As to occupations, the majority (forty-five per cent) were university students from the Escola de Belas Artes do Porto (Porto School of Fine Arts) and the University of Porto. A large number had administrative roles in corporations and banks in Porto city center. The remainder had other diverse professional jobs: a high-school teacher, a sculptor, a fine-art painter, some engineers, and two of Porto’s branch members of the Emissora Nacional de Radiodifusão Portuguesa (Portuguese National Radio Broadcaster).

Among them, a few names stand out: the architect José Maria dos Santos Pulido Valente, Lisbon-born but relocated to Porto in 1955 to enroll in the Architecture course at the Porto School of Fine Arts. And there were some local amateur musicians of the day, such as guitarist Freitas Morna, pianist and vibraphonist Walter Berendt, and pianist Pedro Osório, among others. Unfortunately, most of those amateurs never made studio recordings, so almost all their music was lost. Moreover, as in many other diasporic locations, local jazz amateurs would have had a varied repertoire of styles, depending “on what the popular music of the day offered” (CitationBecker 27). Such was the case for Pedro Osório, who began his musical career on the piano (self-taught), enjoyed a rapid passage through the Conservatório de Música do Porto (“Porto Music Conservatory”), and then dedicated his early career to popular music, participating in groups that animated Porto’s student balls and parties. However, it was through contact with local jazz amateurs, particularly Freitas Morna (guitar) and Vasco Henriques (piano), “that he acquired his first knowledge of harmony and improvisation” (CitationTilly, Martins, and Silva 955). Along with Heinz Worner and Walter Behrend, Morna was in a group known as Walter Behrend e o Seu Conjunto (“Walter Behrend and His Group”), which, a few years later, recorded a cover of the jazz tune “Petit Fleur” by Sidney Bechet, divulging their former jazz tendencies.Footnote47

Lisbon witnessed some jazz–fado crossover projects, such as Popfado – fado being Portuguese national folk song, However, in the period investigated, no jazz–fado connections were identified in Porto.Footnote48 But with regard to crossovers with other musical styles, it is worth mentioning that Walter Behrendt and His Conjunto, like Thilo’s Combo in Lisbon, recorded several EPs featuring styles that were in vogue, such as rock and roll, twist, and bossa nova.Footnote49

In the 1960s, the SJ-CFP lost its original dynamic, as revealed in the internal documentation. Nevertheless, SJ-CFP’s activities were pivotal in the emergence and development of Porto’s jazz scene: a social space characterized by a generation of middle-class educated urban individuals, primarily men. As a side note, the public debut of the Hot Club of Portugal Quartet, which happened “outside the private circuit of the HCP,”Footnote50 was on 5 October 1960, at Porto’s Associação de Jornalismo e Homens de Letras (Journalists and Men of Letters Association).

An example of SJ-CFP’s legacy was the foundation of a second jazz club in Porto in the mid-1960s, which was named, tellingly, the “Jazz Section” of the Portuguese Jeunesse Musicales Porto Delegation (Portuguese Jeunesse Musicales [PJM]), and also known as the Caveaux).Footnote51 In February 1966, Porto’s “1st Week of Jazz” was organized by the Jazz Section and sponsored by the U.S. Embassy in Lisbon (CitationCravinho, Encounters). Elements from both the Lisbon (HCP) and Porto (the newly created “Jazz Section”) scenes participated in these events. In both initiatives, Rocha CitationBrito played a decisive role, revealing his close connection with Villas-Boas and the Lisbon milieu, a fact that should dispel any doubts about whether any such cooperation existed.

On Saturday, March 11, of the following year, a phonographic session was put on by the PJM “Jazz Section,” in collaboration with the Centro Universitário do Porto, in the Salão; CitationNobre of the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Porto. It was delivered by Manuel Jorge Veloso and followed by a jam session with the participation of the Hot Clube de Portugal group.Footnote52 Also notable in this period are concerts featuring German and North American jazz musicians at the Cinema Trindade, which were organized by the PJM, the German Culture Institute, and the Center for Humanistic Studies. One of these showcased the quintet led by pianist Pepsi-Auer and vocalist Willi JohannsFootnote53; another the Albert Mangelsdorff Quintet.Footnote54

By the early 1970s, now under a government led by Dr. Marcello Caetano, the groundwork for a free-jazz youth group had been laid by Jorge Lima Barreto (CitationGuimarães; CitationPaes; CitationQuaresma).Footnote55 This shift from a self-contained aesthetic to a broader musical landscape during the Caetano years had a major impact on its practice and its sense of political awareness, framing jazz as a type of music that calls everything into question (CitationCravinho, “António Pinho Vargas”). Lima Barreto’s explorations into free jazz and improvised music led to the creation of an informal collective called Conceptual Jazz by a group of young musicians from Porto, who averred “that all the effort that the musician makes in the act of creation is a form of protest.”Footnote56 Barreto’s exploratory work around the concept of free jazz, along with the meetings and discussions about jazz, would, over the following years, energize musicians beyond the Porto metropolitan area.

As a side note, the presence of the Modern Jazz Quartet (MJQ) in Porto at the Fourteenth Gulbenkian Music Festival should be mentioned. After a first concert in the Portuguese capital, the MJQ performed at the Rivoli Theater on 22 May 1970, at 9:30 p.m. The event was a significant one for Portuguese music and widely heralded in the national press. It was the first appearance of jazz at a festival usually given over to the celebration of Western classical music.

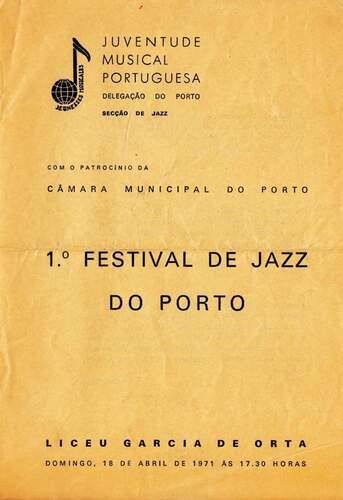

A significant milestone in the Porto jazz scene was the first jazz festival held in the city – 1° Festival de Jazz do Porto – organized by the Jazz Section of the PJM Porto Delegation on 8 April 1971 (see ), and sponsored by Porto’s City Council. Several local jazz musicians who took part in this festival played a crucial role in developing jazz in Portugal over the following decades.

Performing at the 1st Porto Jazz Festival were the Kevin Hoidale Quartet (Hoidale was from the United States),Footnote57 the Portuguese group Contacto, the Hot Club of Portugal Quartet, and the Anar Jazz Group, led Jorge Lima Barreto.Footnote58 A few weeks later, on 26 April 1971, at the Coliseu do Porto, as part of the festivities of Queima das Fitas, another jazz festival was held in Porto, and this one featured the Stan Getz Quartet and Contacto again.Footnote59

Also worth highlighting during this period is the presence of the Millikin University Jazz Lab Band at the Teatro Sá da Bandeira on 9 January 1973. It was an initiative led by the Portuguese Secretariado para a Juventude (Youth Secretariat) and sponsored by both the Portuguese Ministério da Educação (Ministry of Education) and the U.S. Embassy in Lisbon. Thereafter, the Jazz Lab Band set off around the country with concerts in five cities, including Porto.

As a further side note, of interest is an event organized by Lima Barreto and billed as “Jazz-Off,” which took place in Algés, a former civil parish in the municipality of Oeiras, in the Lisbon metropolitan area, at the Clube Primeiro Acto.Footnote60 Barreto’s artistic and literary activity remained intense, especially post-April 1974: As well as leading the Anar Jazz Band, he authored books about jazz and countless music reviews in the national press.Footnote61 He vigorously promoted free jazz as well as the style’s main precursors – as purveyed by both Europeans and African Americans – and, via his acerbic critical writing, made a controversial name for himself by attacking other jazz critics.

After the coup d’état that overthrew the Caetano regime on 25 April 1974, the Porto scene and its musical aesthetics changed significantly.Footnote62

In Conclusion

In recent years, more attention has been paid to the jazz diaspora and its relationship to smaller, provincial towns. Nonetheless, many urban centers and smaller jazz communities remain relatively overlooked, leaving little research available on the different cultural dynamics and infrastructures that distinguish the emergence of jazz communities in these spaces compared to capital cities. As in many other diasporic locations, members of the Porto scene in the late 1950s consumed transnational jazz culture as a “kind of focused activity in which shared meanings” collectively “imagined and diffused in a specific spatial context” (CitationGrazian, 45).

In an initial analysis, the Porto scene might be depicted as a group of jazz enthusiasts and amateurs clustered within a specific geographic location in a delimited space – Porto city center – within a specific period. But a more detailed analysis reveals Porto as a “translocal” jazz scene (to apply CitationPeterson and Bennett‘s typology). It had a strong connection with other key players from the national scene, and, as the activities led by SJ-CFP members reveal, it found ways to mediate global jazz culture and celebrate it locally. The 1950s and 1960s saw a significant increase in jazz activities in the city, yet many of these events would soon be forgotten and remain unknown to subsequent generations. Jazz during this period evinced a kind of duality: It was a genre of an elite, yet it also represented a “language” of change (CitationCravinho, “The ‘Truth’ of Jazz,” CitationCravinho; Essays of Jazz in Portugal).

This article has also tried to rectify any misconceptions about the absence of jazz in Porto’s urban center before April 1974, and about the supposed rivalry between the Lisbon and Porto scenes. On the contrary, during the period investigated, members of both scenes collaborated closely – not just the promoters but also the musicians, as evidenced by the fact that the 1960 Hot Club of Portugal Quartet debut was in Porto and that Luis Villas-Boas was present in Porto during its first “Week of Jazz.” Publications are available on the subject of the Lisbon jazz scene and its promoters, covering Villas-Boas and the Hot Clube de Portugal, and there are also those on the significant International Cascais Jazz Festivals. There are two research projects funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology dedicated to the key Lisbon jazz promoters.Footnote63 However, such attention has been denied to the Porto jazz scene; there is still a lack of research on its development throughout the Estado Novo regime up to April 1974, and its promoters. Brito Guimarães was undoubtedly a central figure in the development of jazz locally.

The Porto postwar jazz scene has therefore, up to now, been a neglected history, one that has failed to be incorporated into the city’s official cultural history. I hope this article will create an opportunity for in-depth comparisons of Porto’s jazz scene post-World War II with those in other provincial cities in a variety of diasporic locations. These stories are so often ignored or marginalized, forming part of an extensive but as yet unwritten history.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pedro Cravinho

Pedro Cravinho is a researcher and educator with a background as a professional musician, a BMus in Musicology and a PhD in Ethnomusicology. He is a Senior Research Fellow at Birmingham Centre for Media and Cultural Research (BCMCR), the Keeper of the Archives at the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University, UK, and a member of CITCEM – Transdisciplinary Research Center «Culture, Space and Memory» at the University of Porto, Portugal. Cravinho co-leads the BCMCR Jazz Studies Research Cluster and teaches jazz at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. His research interests lie, broadly, in the social, political and cultural history of the jazz diaspora, and its representation in the media and the public sphere in general. He is a co-founder and board member of the Portuguese Jazz Network (PT), a Trustee for the National Jazz Archive and Archives West Midlands, UK, and a board member of the Scottish Jazz Archive and the Duke Ellington Society, UK. Cravinho is a co-founder of the Documenting Jazz international conferences and a co-investigator in the AHRC/NEH project ‘New Directions in Digital Jazz Studies’. He is a member of the editorial board of the jazz research journal Jazz-hitz(Musikene, Spain), and his publications include key research about the history of jazz in Portugal, including Encounters with Jazz on Television in Cold War Era Portugal, 1954-1974 (Routledge, 2022).

Notes

1. Dedicated to the memory of Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães (31 December 1927–23 February 2017). This article is an output of my postdoctoral project on the same topic conducted at CITCEM – Transdisciplinary Research Center «Culture, Space and Memory» at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities of the University of Porto. The author would like to thank the editors, Adam Havas and Bruce Johnson, and the two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of this article and their insightful commentaries and useful suggestions. A special thanks go to Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães; to several Board members of the Clube Fenianos Portuenses, namely Fernando Coimbra, Fernando Rocha, Paulina Sousa, and Cristina Mouta; and also to Hélder Pacheco, Ana Lopes, and Dean Bargh.

2. Recently, CitationFrancesco Martinelli has co-led a significant English-language project, published in 2018, shedding light on European jazz scenes, local musicians, and foreign visitors.

3. I (Pedro Cravinho) have published a historical overview of jazz in Portugal in both Jazz Research Journal (“Historical”) and The History of European Jazz (“Portugal”), a bilingual book about jazz in Coimbra (Essays), and an essay about a vital contributor to Porto’s jazz scene, António Pinho Vargas (“António”). On Portugal, see also CitationSantos and Rubio. On Spain, see CitationBaulenas; CitationRodríguez; CitationOlivera; CitationPalacios.

4. I struggled to find participants who were able to recall their experiences. Notwithstanding that, my research has benefited immeasurably from the support of the Club Fenianos Portuenses.

5. Leonardo CitationSanchez; has conducted an ethnographic study of Porto’s jazz scene, focusing on the creation and expansion of Associação Porta-Jazz (the Porta-Jazz Association) since 2010.

6. Salazar stayed in power until illness forced him out of office in 1968. He was followed by Dr. Marcello Caetano (1968–1974), who, to some extent, continued the same domestic politics during a period that came to be known as Marcellism.

7. The Portuguese Constitution was approved on 19 March 1933, and officially launched on 11 April 1933.

8. CitationFaria later assembled his articles in a book, Os Bailes e a Acção Católica.

9. “Nas colectividades de recreio.” Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo: Ministério do Interior: Direcção Geral de Administração Política e Civil (“Ministry of the Interior: General Directorate of Political and Civil Administration “). Process No. 01/30, “Dança denominada “Swing”“ (“Dance designated “swing”“). Federação das Sociedades de Educação e Recreio, Letter No. 1542/942 (8 December 1942). All translations from Portuguese sources are by the author. It is the author’s hope that opening up these sources to non-Portuguese readers adds to the value of this study. In each case, the original text is included in an endnote, as here, for the benefit of Portuguese speakers.

10. “dança denominada ‘SUWNG’ [sic] que pelo ser compasso acelarado [sic] e exaustivo bem como a maneira como é executada e o exagero de posições traz [sic] consequencias [sic] desagradáveis.” (Ibid.).

11. “afectando a moral independentemente da falta de compostura” (Ibid.).

12. “Não tenho elementos para apreciar a natureza, o aspecto, e as consequencias [sic] da dança a que se refere este oficio … dirigir e orientar as suas festas pelo modo mais conveniente para a moral e para a higiene.” Handwritten notes in Letter No. 1542/942 (12 December 1942).

13. Manuel Rocha Guimarães, interview with Pedro Cravinho, March 2014.

14. “Pela 1a vez no Porto um autêntico Jazz Band.” O Primeiro de Janeiro, 4 February 1923, p. 2.

15. Some of the jazz bands that played regularly in Porto adopted the name of the venue where they performed: Examples from this period are the Orquestra Invicta Jazz, Sá da Bandeira Jazz, Jazz Odeon, Foz Melody Jazz, and Oriental Band-Jazz.

16. “Atraz do reposteiro” (Behind the curtain), O Diário de Lisboa, 11 January 1928, p. 5.

17. According to the French jazz writer Gérard Conte, Sidney Bechet crossed the Portuguese border in Vilar Formoso on 31 December 1927, as part of the Louis Douglas company (CitationMartins).

18. O Primeiro de Janeiro, 16 April 1931, p. 4.

19. O Primeiro de Janeiro, 5 May 1931, p. 4.

20. “Tive porem que substituir por homens duas delas, visto serem russas e não podem entrar em Portugal. Devo dizer que estou gratíssimo as gentis facilidades que tive por parte da alfandega e da Policia Internacional de Lisboa [PIDE].” “Um Jazz de mulheres” (A jazz of women), Diário de Lisboa, 30 March 1935, p. 7.

21. What is known is that a significant jazz event took place in Porto in March 1941 with Josephine Baker’s debut at the Teatro Sá da Bandeira (CitationCravinho, “Black Angel”).

22. Armando Leça was the pseudonym of Armando Lopes (9 August 1891–7 September 1977), a Portuguese composer, choral conductor, and folk song collector.

23. Author’s Collection: Facsimile letter of 4 May 1946, from Luís Villas-Boas to Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães.

24. Among those authors who are aware of him, some have referred to Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães as the “Villas-Boas of Porto” (CitationMartins; CitationCurvelo).

25. Author’s Collection: Facsimile letter of 19 March 1948, from Villas-Boas to Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães.

26. Author’s Collection: Facsimile letter of 31 January 1950, from Villas-Boas to Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães.

27. Since the 1930s, this store had been advertising, in the local press, its “Fox-Trot,” “Charleston,” and “Jazz” records.

28. Author’s Collection: Correspondence between Luís Villas-Boas and Manuel Rocha Brito Guimaraes, 1946–1956.

29. “Manuel Rocha Brito Guimaraes–Sócio correspondente N.° 1 HCP” (Manuel Rocha Brito Guimaraes–Correspondent member No. 1 HCP), Hot News, no. 2, May 2010, no pagination [page 7].

30. “História de Jazz [History of Jazz]. Iniciando uma série de actividades culturais sobre o tema da modernidade, realizar-se-á hoje nos Fenianos a primeira sessão de música de jazz.” Diário do Norte, 28 March 1957, p. 4.

31. Founded on 25 March 1904, the club was initially located in Praça da Batalha but in 1935 moved to no. 28, at the very top of Avenida dos Aliados, next to Porto City Hall (CitationBrito). Since the 1930s, the CFP had been advertising, in the local press, balls featuring jazz bands.

32. Clube Fenianos Portuense, Party Committee: Official Letter no. 1/57 (28 January 1957).

33. “Sessão de música de ‘Jazz’, nos Fenianos [Jazz Music Session in the Fenianos]. Prosseguindo uma serie de actividades culturais, realizar-se-á, amanhã, às 21 horas e meia, no Clube Fenianos Portuenses a segunda sessão de música de jazz sob a orientação de Adelino Felgueira, Jorge Baptista e Raul Testor Hestnos.” Diário do Norte, 3 April 1957, p. 7.

34. “CLUBE FENIANOS PORTUENSES … Continuando a obra de divulgação cultural iniciada com superior interesse no campo especial da música de jazz, realiza-se amanhã pelas 21,30 horas, a terceira sessão que terá como comentadores os srs. dr. Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães, Manuel Begonha Perry Câmara e António Nobre.” “Clube Fenianos Portuenses,” Jornal de Notícias, 25 April 1957, p. 3.

35. For further discussion on the Clube Fenianos Portuenses and its opposition to the New State regime, see CitationAlmeida.

36. “Secção de música de Jazz: Em virtude de uma actividade artística promovida pelo nosso sócio Sr. Hélder Veiga Pires, e realizada por um grupo de cultores de música de jazz, e que despertou interesse, atraindo um número apreciado de jovens. Foi resolvido aceitar a formação desta Secção, a pedido da componente daquele Grupo … sendo Diretor-Delegado o Sr. Dário Ramos Júnior.” Minute No. 1255/1957. CFP, Board Minutes Book, 1955–1959.

37. Minute No. 1255/1957. CFP, Board Minutes Book, 1955–1959.

38. “Secção de JAZZ que trouxe ao clube muitos mais associados.” Minute of the General Assembly held on 11 December 1957. CFP, Board Minutes Book, 1955–1959.

39. The Orquestra Sinfónica do Porto was subsequently transferred to the Porto branch of the Emissora Nacional Portuguesa (National Broadcasting Service).

40. Highlights in 1957 were piano concerts by Marilia Vaz and Eurico Tomaz de Lima, the Orquestra Sinfonica do Porto conducted by conductor Fernando Cabral, and a recital by singer Maria Luisa Homero and pianist Fernando Jorge Azevedo. There were also lectures by Maestro Joly Braga Santos on “The Musical Evolution of the Twentieth Century” and by Nichel Agnellet on folklore.

41. “SECÇÃO DE JAZZ [sic]. Foi criado mais uma Secção Cultural cujos merecimentos foram postos à prova, em algumas realizações levadas a efeito, e que atraíram ao Clube um número de pessoas interessadas na divulgação e conhecimento da música especifica do Jazz. Dirigida por um grupo de experts, e artistas, sobejamente conhecidos no meio musical, a sua actividade mereceu apreciações de simpatia. Fazemos sinceros votos para que os dirigentes da Secção, possam continuar a obra iniciada, aliás, sob bons auspícios, de acordo com as responsabilidades culturais que tomaram, tao dedicadamente, sob os seus ombros.” Report, Accounts and the Supervisory Board Statement for 1957, approved at the Annual General Meeting on 22 March 1958. CFP, Report and Accounts – Audit Board. Financial Year 1957.

42. The accounts reveal the purchase of a double bass for the Jazz Section in mid-January 1958, for the sum of 2.500 USD00 (i.e. 2,500 Portuguese Escudos). CFP – Accounting Book – Year 1958, p. 31.

43. The CFP cinema sessions are also worthy of note. The Cineclube do Porto (founded in 1945), along with theater – represented by the University Theater of Porto (founded in 1948) and the Experimental Theater of Porto (founded in 1953) – made a significant contribution to the cultural dynamics of postwar Porto.

44. Report, accounts, and the supervisory Board statement for 1958 approved at the Annual General Meeting on 27 March 1959. CFP, Report and Accounts – Audit Board. Financial Year 1958.

45. Brito Guimarães and Manuel Nobre together produced the Jazz show on Radio Clube Português, broadcast fortnightly on Thursdays from 9:45 to 10:15 p.m.

46. The Portuguese scene remained persistently male-dominated over the following decades.

47. Dance com Walter Behrend e o Seu Conjunto (Alvorada, 1960 [MEP 60250], 4-track EP). In the 1960s, Walter Behrend e o Seu Conjunto featured Walter Behrend (piano and vibraphone), Lourenço Pereira (drums), José Ricardo (double bass), Cassiano (electric guitar), Rui Pereira (accordion), and Pedro Nuno (vocals).

48. See CitationCravinho, “Jazz in fado/fado in jazz.”

49. Em Tempo de Twist (Orfeu, n.d. [ATEP 6037], 4-track EP) and Bossanova (Orfeu, n.d. [ATEP 6040], 4-track EP).

50. “fora do circuito privado do HCP” (CitationBernardo, p. 1,074).

51. During my fieldwork I had the opportunity to visit the venue and see the jazz club’s original double bass and drums. Unfortunately, I have been denied access to membership files and other internal documentation.

52. For further discussion on Manuel Jorge Veloso, see CitationCravinho (Encounters).

53. Featuring the Americans Don Menza (tenor saxophones) and Dick Spencer (alto saxophone), and the Germans Ernst Knauff (double bass) and Klaus Weiss (drums).

54. Featuring Günter Kronberg (alto, baritone saxophones, and clarinet), Heinz Sauer (soprano and tenor saxophones), Günter Lenz (double bass), and Ralf Hübner (drums).

55. Jorge Lima Barreto (26 December 1949–9 July 2011) was a composer, instrumentalist (piano and other keyboard instruments), writer, and critic. He led the group the Anar Band, the duo Telectu, and the duo Zul Zelub. From 1967 until his death, he published several books on rock, jazz, electronic music, and improvised music; as a critic, he wrote regularly for several Portuguese periodicals.

56. “todo o esforço que o músico realiza no acto de criação é uma forma de protesto.” Conceptual Jazz press release (25 January 1973).

57. Kevin Hoidale (15 February 1941–11 February 2012) was a North American instrumentalist (piano and keyboards) and arranger, resident in Portugal in the late 1960s to the mid-1970s.

58. The Kevin Hoidale Quartet featured Kevin Hoidale (piano and electric piano), João Ramos Jorge (tenor saxophone), Jean Sarbib (electric bass), and Victor Mamede (drums); the Anar Jazz Group featured Jorge Lima Barreto (piano and percussion), Paco Linhares (organ), Pedro Proença (cello), Sérgio (electric guitar and bass), and David Sá (drums); Contacto featured Rui Cardoso (flute and tenor saxophone), Marcos Resende (piano), Nuno Gonçalves (double bass), and Paulo Gil (drums); and the Hot Club of Portugal Quartet featured Vasco Henriques (flute), Justiniano Canelhas (piano), Bernardo Moreira (double bass), and Manuel Jorge Veloso (drums).

59. The Stan Getz Quartet featured Stan Getz (tenor saxophone), the French musicians Eddy Louiss (Hammond organ) and Bernard Lubat (drums), and the Belgian jazz guitarist René Thomas.

60. Rádio & Televisão, 863: 35–36 (28 May 1973).

61. Revolução do Jazz (Jazz Revolution) and Jazz-Off. Although published in 1973, the latter was actually written in 1971, according to the author (CitationBarreta, Revolução 315).

62. Important events of that period were the national jazz meetings in Porto organized by the Student Association of the Porto Faculty of Economics and the local group Abralas, which featured Carlos Machado (trumpet), José Nogueira (alto and tenor saxophone), Carlos Araújo (electric bass), António Pinho (piano), José CitationMartins (percussion), and Zé Rato (drums).

63. The first was conducted in the Portuguese Institute of Ethnomusicology (INET-md) and held at the INET-md branch of the University of Aveiro (INET-md /UA). It was designated Os Mensageiros do Jazz em Portugal no século XX (“The Jazz Messenger in Portugal in the Twentieth Century”; PTDC/EATMMU/102624/2008). The second one was held at the INET-md branch of the Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa (INET-md/FCSH-UNL) and was designated Os Legados de Luís Villas-Boas e do Hot Clube de Portugal (“The Legacy of Luis Villas-Boas and the Hot Clube de Portugal”; PTD/EAT-MMU/121834/2010).

Works Cited

- Almeida, Henrique. O Clube Fenianos Portuenses na oposição ao Fascismo na década de 40. No publisher idekntified. 1982.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflection on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev., Verso, 2006.

- Atkins, E. Taylor. Jazz Planet: Transnational Studies of the “Sound of Surprise” UP of Mississippi, 2003.

- Ballantine, Christopher. Marabi Nights: Early South African Jazz and Vaudeville, Ravan P, 1993.

- Barreto, Jorge Lima. Jazz-Off, Paisagem Editora, 1973.

- Baulenas, Jordi Pujol. Jazz en Barcelona, 1920–1965, Almendra Music, 2005.

- Becker, Howard S. “Jazz Places.” Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual, edited by Andy Bennett and Richard A. Peterson, Vanderbilt UP, 2004, pp. 17–27.

- Bernardo, Raul Vaz. “Quarteto Do Hot Clube de Portugal.”.” Enciclopédia da Música Em Portugal No Século XX, edited by Salwa Castelo-Branco, Temas e Dabates/ Círculo de Leitores, P-Z, 2010, pp. 1,074.

- Bohlman, Phillip V., and Goffredo Plastino editors. Jazz Worlds / World Jazz, U of Chicago P, 2016.

- Brito, Sandra Clube Fenianos Portuenses: Um Projecto de Civilização, uma Busca de Projecção. 2003. U of Porto, master’s thesis.

- Bryant, Clora, et al, editors. Central Avenue Sounds: Jazz in Los Angeles. U of California P, 1998.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “António Pinho Vargas, o músico de ‘jazz-que-não-era-jazz.” Glosas, no. 14, 2016a, pp. 32–36.

- Cravinho, Pedro. Essays of Jazz in Portugal: Jazz in Coimbra, Jazz ao Centro Clube, 2016b.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “Historical Overview of the Development of Jazz in Portugal, in the First Half of the Twentieth Century.” Jazz Research Journal, vol. 6, no. 2, 2016c, pp. 75–108. doi:10.1558/jazz.v10i1-2.30175.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “A Kind of ‘In-Between’: Jazz and Politics in Portugal (1958–1974).” Jazz and Totalitarianism, edited by Bruce Johnson, Routledge, 2017, pp. 218–38.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “Portugal: 1920–1974.” The History of European Jazz: The Music, Musicians and Audience in Context, edited by Francesco Martinelli, Equinox, 2018a, pp. 461–69.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “The ‘Truth’ of Jazz: The History of the First Publication Dedicated to Jazz in Portugal.” jazz-hitz, no. 1, 2018b, pp. 57–72.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “The ‘Black Angel’ in Lisbon: Josephine Baker Challenges Salazar, Live on Television.” EU-topías, 18, 2019, pp. 123–33.

- Cravinho, Pedro. Encounters with Jazz on Television in Cold War Era Portugal, 1954–1974, Routledge, 2022.

- Cravinho, Pedro. “Jazz in Fado / Fado in Jazz: Encounters between Jazz and Fado in Portugal (Part 1).” Jazzforschung / Jazz Research, no. 51, forthcoming.

- Curvelo, António. “Manuel Rocha Brito Guimarães.”.” Enciclopédia da Música Em Portugal No Século XX, edited by Salwa Castelo-Branco, Temas e Dabates/ Círculo de Leitores, C-L, 2010, pp. 590.

- Faria, António Gonçalves Molho de. Os Bailes e a Acção Católica. 1st, Tipografia Oficina de S. José, 1939.

- Faria, António Gonçalves Molho de. Os Bailes e a Acção Católica. 2nd, Tipografia Oficina de S. José, 1947.

- Fox, Charles. Jazz in Perspective, British Broadcasting Corporation, 1969.

- Grazian, David. “The Symbolic Economy of Authenticity in the Chicago Blues.” Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual, edited by Andy Bennett and Richard A. Peterson, Vanderbilt UP, 2004, pp. 31–46.

- Guimarães, Manuel António Oliveira Práctica e Receção da Música Improvisada em Portugal: 1960 a 1980. 2013. Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Master’s Thesis.

- Harris, Rex. Jazz. Trans. Raul Calado. : Ulisseia. 1962.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. The Jazz Scene, Monthly Review P, 1960.

- Jackson, Travis A. Blowin’ the Blues Away: Performance and Meaning on the New York Jazz Scene, U of California P and Center for Black Music Research, 2012.

- Jago, Marian. Live at the Cellar: Vancouver’s Iconic Jazz Club and the Canadian Co-operative Jazz Scene in the 1950s and ‘60s, UBC P, 2018.

- Johnson, Bruce. “The Jazz Diaspora.” The Cambridge Companion to Jazz, edited by Mervyn Cooke and David Horn, Cambridge UP, 2002, pp. 33–54.

- Johnson, Bruce. Jazz Diaspora: Music and Globalisation, Routledge, 2019.

- Leça, Armando. “Da Caninha Verde à Sonata.” Arte Musical, May 20, 1938.

- Martinelli, Francesco editor. The History of European Jazz: The Music, Musicians and Audience in Context, Equinox, 2018.

- Martins, Hélder Bruno de Jesus Redes. O Jazz em Portugal (1929–1956): Anúncio–Emergência–Afirmação, Edições Almedina, 2006.

- Melo, Daniel. Salazarismo e Cultura Popular (1933–1958), Imprensa de Ciências Sociais, 2001.

- Myers, Marc. Why Jazz Happened, U of California P, 2013.

- Neves, Helena, and Maria Calado. Estado Novo e as Mulheres: O Género como Investimento Ideológico e de mobilização, Biblioteca Museu República e Resistência, 2001.

- Nobre, José Luiz. “On Oporto Air.” Down Beat, vol. 18, no. 15, 27 July 1951, pp. 10.

- Olivera, Antonio Torres. Jazz en Sevilla, 1970-1995: Ensoñaciones de una época, Diputación de Sevilla, 2015.

- Paes, Rui Eduardo. “Portugal: 1974–2000.” The History of European Jazz: The Music, Musicians and Audience in Context, edited by Francesco Martinelli, Equinox, 2018, pp. 470–81.

- Palacios, Patricio Goialde. Orígenes de la música de jazz en San Sebastián (1919–1936), Universidad del País Vasco-Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, Musikene-Centro Superior de Música del País Vasco y Eresbil-Archivo Vasco de la Música, 2020.

- Panassié, Hugues. História do Verdadeiro Jazz, Portugália. Trans. Raul Calado. 1964.

- Quaresma, André de Oliveira Jazz-Off: A Música de Jorge Lima Barreto na década de 1970. 2021. U of Coimbra, master’s dissertation.

- Rasula, Jed. “The Media of Memory: The Seductive Menace of Recording in Jazz History.” Jazz among the Discourses, edited by Krin Gabbard, Duke UP, 1995, pp. 134–62.

- Richard A., Peterson and Andy, Bennett, edited by. Music Scenes: Local, Translocal and Virtual 2004 Introducing Music Scenes. Vanderbilt UP, pp. 1–15.

- Rodríguez, Vicent Lluís Fontelles Jazz a la ciutat de València: Orígens y desenvolupament fins a les acaballes del 1981. 2011. Universitat Politècnica de València, PhD dissertation.

- Said, Edward. Musical Elaborations. Vintage, 1991. .

- Sanchez, Leonardo Pellegrim A Malta do Norte: Um Estudo Etnográfico Sobre a Cena do Jazz Portuense. 2020. PhD dissertation, University of Aveiro.

- Santos, João Moreira dos. O Jazz Segundo Villas-Boas, Assírio & Alvim, 2007.

- Santos, João Moreira dos, and António Rubio. Jazz na Terceira: 80 Anos de História, Bluedições, 2008.

- Stewart, Alex. Making the Scene: Contemporary New York City Big Band Jazz, U of California P, 2007.

- Straka, Manfred. “Cool Jazz in Europe.” Eurojazzland: Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics, and Contexts, edited by Luca Cerchiari, Laurent Cugny, and Franz Kerschbaumer, Northeastern UP, 2012, pp. 214–34.

- Straw, Will. “Systems of Articulation, Logics of Change: Communities and Scenes in Popular Music.” Cultural Studies, vol. 5, no. 3, 1991, pp. 363–88. doi:10.1080/09502389100490311.

- Tilly, António, Catarina Martins, and Hugo Silva. “Osório, Pedro Correia Vaz.” Enciclopédia da Música em Portugal no Século XX, edited by Salwa Castelo-Branco, Vol. L–P, Temas e Dabates / Círculo de Leitores, 2010, pp. 954–57.

- Vaquinhas, Irene. “A família, essa ‘pátria em miniatura.” Historias da Vida Privada em Portugal: A Época Contemporânea, edited by José Mattoso, Círculo de Leitores, 2011, pp. 118–51.