Abstract

Background and objective: People with T2DM who initiate basal insulin therapy often stop therapy temporarily or permanently soon after initiation. This study analyzes the reasons for and correlates of stopping and restarting basal insulin therapy among people with T2DM.

Methods: An online survey was completed by 942 insulin-naïve adults with self-reported T2DM from Brazil, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, UK, and US. Respondents had initiated basal insulin therapy within the 3–24 months before survey participation and met criteria for one of three persistence groups: continuers had no gaps of ≥7 days in basal insulin treatment; interrupters had at least one gap in insulin therapy of ≥7 days within the first 6 months after initiation and had since restarted basal insulin; and discontinuers stopped using basal insulin within the first 6 months after initiation and had not restarted.

Results: Physician recommendations and cost were strongly implicated in patients stopping and not resuming insulin therapy. Continuous persistence was lower for patients with more worries about insulin initiation, greater difficulties and weight gain while using insulin, and higher for those using pens and perceiving their diabetes as severe. Repeated interruption of insulin therapy was associated with hyperglycemia and treatment burden while using insulin. Resumption and perceived likelihood of resumption were associated with hyperglycemia upon insulin cessation. Perceived likelihood of resumption among discontinuers was associated with perceived benefits of insulin.

Conclusion: Better understanding of the risk factors for patient cessation and resumption of basal insulin therapy may help healthcare providers improve persistence with therapy.

Introduction

Treatment guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) recommend a stepwise approach to glycemic control, including use of basal insulin as one line of treatmentCitation1–4. Insulin is the most effective therapy for lowering blood glucose levels, which helps prevent or delay the development of microvascular and macrovascular complicationsCitation4,Citation5. However, effective long-term implementation of insulin therapy requires attainment of four sequential milestones: initiation (filling a prescription and administering the medication), persistence (continued use), adherence (taking the medication as prescribed), and intensification (taking higher doses or more frequent doses of the medication as needed). Adherence is the most studied of these milestones; factors associated with non-adherence include regimen-related factors (e.g. difficulty and complexity) as well as patient-related factors (e.g. beliefs about medication, depression)Citation6–9. While it may be difficult to overcome barriers to adherence, those barriers are well known.

Recently there has been increased attention to the milestone of medication initiation with the recognition that many patients who could benefit from insulin therapy are never offered a chance to obtain this treatmentCitation10. Some physicians are reluctant to prescribe insulin, most importantly due to clinical inertiaCitation11, and many patients are reluctant to take it even when prescribed. Surveys of insulin-naïve T2DM patients in the US found that 28–33% of respondents were unwilling to take insulin if prescribedCitation12,Citation13. In the DAWN2 study of over 4500 insulin-naïve patients with T2DM in 17 countries, 43% of those not taking anti-hyperglycemic medication and 38% of those taking oral anti-hyperglycemic medication were unwilling to initiate insulin if recommended by their healthcare providerCitation14.

Persistence is another milestone in the implementation of insulin therapy. Many patients who initiate insulin therapy discontinue at some point, either temporarily or permanently. Retrospective claims studies of insulin-naïve populations in the US showed that only 18–20% of the people with T2DM who initiated insulin continued treatment in the year after initiation without any interruption or discontinuationCitation15,Citation16. In one study 62% had one or more interruptions, and 18% discontinued therapy in the year after basal insulin initiationCitation16. The US is not unique in this regard; in a survey of insulin-naïve T2DM patients in Turkey initiating insulin therapy, 20% reported treatment discontinuationCitation17.

Another therapeutic milestone receiving increased attention is the process of medication intensification. Clinical inertia may lead to dosage stagnation in the face of need for increased dosing. There are several recommended strategies for titrating basal insulin doses to meet patient needsCitation18, and basal-plus or basal–bolus therapy is a strategy for enhancing prandial insulin levels when the limits of basal insulin titration have been reachedCitation19.

While adherence is the most researched therapy implementation milestone, logic indicates that initiation and persistence take precedence in clinical practice. Adherence to the insulin regimen is not an issue if patients do not initiate therapy, and even if they do initiate therapy, adherence and intensification are relevant only as long as patients continue their treatment. Therefore, better understanding of the factors associated with insulin persistence, and more specifically with different patterns of persistence (continuous persistence, interruption, and discontinuation), is critical for clinicians treating people with T2DM initiating basal insulin therapy.

The objective of this study was to identify patient-reported reasons for and factors associated with multiple outcomes related to basal insulin therapy persistence among insulin-naïve adults with T2DM, i.e. the onset or avoidance of extended (>7 days) stoppage of insulin therapy (including repeat episodes), and resumption or discontinuation of insulin therapy.

Patients and methods

Data source

An online survey was administered to participants from the US, UK, Germany, Spain, France, Brazil and Japan between July and September 2015. Potential participants for this study were identified from lists (panels) created and maintained by survey sample companies that consist of persons who have volunteered to be contacted to participate in surveys. Potential participants were identified from the Harris Panel, and panels from Branded Research, Survey Sampling International, and Toluna. No personal identifying information was collected, and exemption from review was granted by Western Institutional Review Board due to minimal risk to participants. Participants who volunteered and qualified for the study were compensated for their time according to the compensation policies of the panel administrators and the study sponsor.

Sample design

Selection criteria were: (1) insulin-naïve adults (age ≥18 years) with self-reported T2DM and (2) those who had initiated a basal insulin analog (i.e. insulin glargine, insulin detemir, or insulin degludec) within 3–24 months before the survey.

Patients had to meet the criteria for one of three patterns of basal insulin persistence: (1) continuers had no gap of at least 7 days in basal insulin treatment; (2) interrupters had interrupted basal insulin (for at least 7 days) at least once within the first 6 months after basal insulin analog initiation and subsequently restarted on any basal insulin by survey completion; (3) discontinuers had stopped using basal insulin (for at least 7 days) within the first 6 months after basal insulin initiation and subsequently did not restart on any type of basal insulin by survey completion.

Exclusion criteria were: pregnancy or breastfeeding at or after insulin initiation.

A target quota of 50 respondents per persistence category was established for each of seven countries included in the study (Brazil, France, Germany, Japan, Spain, UK, US). Recruitment ended when the quota was reached or recruitment plateaued.

Measures

For the purpose of analysis, the survey questions were classified into seven major categories (Cronbach’s alpha is shown as a measure of internal consistency for each multi-item scale scored as the mean for all included items).

Control variables: country; time from basal insulin initiation to the survey (1 = 3–6 months, 2 = 7–12 months, 3 = 13–24 months).

Insulin initiation precursors: these comprise a set of demographic and disease characteristics: gender (male = 1, female = 0); age (years); education (college graduate = 1, not = 0); partnered (yes = 1, no = 0); prescription insurance coverage (yes = 1, no = 0); duration of diabetes (years); prior diabetes medications (oral, yes = 1, no = 0; non-insulin injection, yes = 1, no = 0).

Insulin initiation experience: source of insulin initiation recommendation (primary care physician [PCP] , endocrinologist, diabetes educator, other); inclusion of patient in insulin initiation decision (1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = somewhat, 4 = very, 5 = fully); motivations for insulin initiation (yes = 1, no = 0); perceived diabetes severity (mean of 3 items scored 1 = strongly disagree through 5 = strongly agree; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69); insulin worry (mean of 12 items scored 1 = strongly disagree through 5 = strongly agree; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92); insulin initiation information availability and helpfulness (5 items scored 2 = helpful, 1 = somewhat helpful, 0 = not helpful/did not use/not available; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75); insulin initiation support source availability and helpfulness (mean of 4 items scored 2 = helpful, 1 = somewhat helpful, 0 = not helpful/did not use/not available; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75); confidence about insulin therapy (1 = not at all confident, 2 = somewhat confident, 3 = confident, 4 = very confident); sources of insulin training (count of 6 items, possible range = 0–6); injection device (pen vs. syringe).

Insulin use experience: presence (yes = 1, no = 0) of adverse events (uncontrolled hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia symptoms, weight gain); insulin use difficulty (mean of 9 items scored 1 = not at all difficult, 2 = somewhat difficult, 3 = difficult, 4 = very difficult; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91); positive/negative insulin impact (mean of 14 items scored 1 = very negative through 5 = very positive; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94); insulin burden (mean of 14 items scored 1 = strongly disagree through 5 = strongly agree; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94); follow-up information helpfulness (mean of 3 items scored 2 = helpful, 1 = somewhat helpful, 0 = not helpful/did not use/not available; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77); follow-up support helpfulness (mean of 4 items scored 2 = helpful, 1 = somewhat helpful, 0 = not helpful/did not use/not available; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79).

Insulin cessation effect: hyperglycemia upon insulin cessation (yes = 1, no = 0). This factor was only assessed for those who stopped using their basal insulin at least temporarily.

Reasons for persistence pattern: respondents were given a list of pre-established reasons to select from, and were allowed to volunteer additional responses. Continuers had a unique set of response options. The list of pre-established reasons for stopping and resuming basal insulin was the same for interrupters and discontinuers.

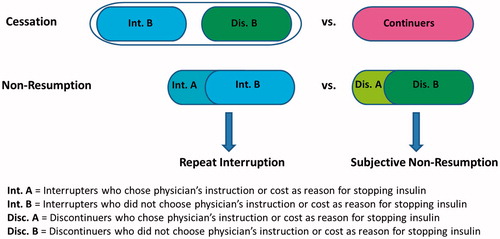

Outcomes: All measures scored as the alternative to persistence: (1) cessation of insulin use ([continuers = no] = 0, [interrupters and discontinuers = yes] = 1); (2) non-resumption of insulin use ([interrupters = no] = 0, [discontinuers = yes] = 1); (3) repeat interruption of insulin use among interrupters, yes = 1 versus no = 0; (4) subjective likelihood of non-resumption of insulin use among discontinuers (4 ordinal categories scored 1 = very likely, 2 = somewhat likely, 3 = slightly likely, 4 = not at all likely). Note that the outcomes can be arranged in a temporal order, i.e. one must first stop using insulin before one can be in the position to consider resumption or actually resume use (or not), and one must restart insulin before one can be in the position to have another interruption.

Analysis

Unadjusted frequencies (and percentages) of self-reported reasons for continuation, interruption/discontinuation, and resumption of insulin therapy are reported. To control for differences among countries, all this data was weighted so that country sample sizes within each subgroup were equal in size.

The analyses assessed correlates of four outcomes: (1) cessation of insulin use, yes/no (comparison of interrupters + discontinuers versus continuers); (2) non-resumption of insulin use, yes/no (comparison of discontinuers versus interrupters); (3) repeat interruption of insulin use, yes/no (subgroup analysis of interrupters); (4) subjective likelihood of non-resumption of insulin use (subgroup analysis of discontinuers). The subjective likelihood of non-resumption of insulin use among people who were not taking insulin at the time of the survey is an approximation of behavioral intention and was analyzed as a proxy for future behavior. A diagram illustrating the outcomes is shown in .

All outcomes were analyzed using multivariate regression to eliminate confounding among risk factors and assess their "independent" associations with the outcomes: logistic regression for cessation, non-resumption, and repeat interruption, and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for subjective likelihood of non-resumption. All regression analyses were conducted with unweighted data using SPSS, version 18. Analyses were performed using an inclusion criterion that was hierarchical (performed one block at a time in the following order: demographic and disease, insulin initiation, insulin use, reasons for cessation, post-cessation, control variables) and stepwise (backward elimination of non-significant variables, p > .05). In order to minimize confounding, education and marital status were retained in all models though not statistically significant. All models controlled for country of residence, although these results are not reported in the regression tables nor discussed in the text (due to the fact that ratios of groups to one another are a function of sample design quotas, not representative of population proportions). Length of time from insulin initiation to the survey is a control variable included in all models to account for differences in recall and is also not reported in the tables or discussed in the text. Final models were estimated with all relevant variables included in the models for all outcomes.

Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) or betas (unstandardized regression coefficients) with 95% confidence intervals for variables in the final models. The incremental blockwise increase and final R2 (Nagelkerke for binary outcomes) are reported; final R2 statistics do not include variance explained by control variables.

Exploratory analyses were performed to determine whether it would be necessary to purify the sample for the analysis of cessation by eliminating patients who stopped their insulin due to their physician’s instructions or due to cost. Physician’s instructions and cost were considered by the authors as non-patient-driven factors because they do not reflect patients’ attitudes, beliefs or experiences regarding insulin. These non-patient-driven factors were only available for the interrupters and discontinuers, thus it was not possible to control for them in the analysis of cessation (continuers vs. interrupters and discontinuers combined). As a result, in the analysis of cessation, the inclusion of patients who discontinued insulin due to physician’s instruction or cost could wash out the true association of other patient factors with cessation. Results of exploratory analyses indicated that several patient factors were related to cessation only for the purified sample. On the other hand, the non-patient-driven factors could be controlled for in the analyses of the other outcomes (i.e. non-resumption, repeat interruption, and subjective non-resumption) because these analyses examined only the interrupters and the discontinuers. Results of exploratory analyses indicated that several patient factors were related to these outcomes only when the non-patient-driven reasons for cessation were controlled in the analyses. Based on the findings discussed above, the analysis of cessation excluded the 209 cases with cessation driven by the physician or cost, leaving 733 cases for analysis of this outcome. However, for the analyses of other outcomes, the full sample of interrupters and discontinuers was used, and non-patient-driven factors were included as covariates.

Results

reports the sample characteristics for all measures retained in the multivariate regression models. A more detailed reporting of sample and subgroup characteristics can be found in an earlier publicationCitation20. Briefly, all countries except Japan (n = 83) contributed between 130 and 160 respondents. There were 357 continuers, 330 interrupters, and 255 discontinuers. Most participants were male (64.7%), college graduates (51.8%), partnered (75.7%), and had prescription insurance coverage (78.6%). The mean age was 40.4 years and the mean duration of diabetes was 7.0 years. Over half (65.3%) of patients had prior use of any other anti-hyperglycemic medication with 57.6% of participants having taken oral anti-hyperglycemic medications and a quarter (24.3%) having taken injections of non-insulin diabetes medication.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N = 942 except as noted).

For the outcomes, 376 of 733 cases (51.3%) had stopped insulin, 255 of 585 cases (43.6%) had not resumed insulin, and 210 of 330 cases (63.6%) had multiple insulin interruptions. The mean (±SD) of subjective likelihood of insulin non-resumption was 2.3 (±0.9) on a scale of 1 (very likely) to 4 (not at all likely), the average of the distribution closer to somewhat likely; 60.3% of discontinuers said that they were slightly or not at all likely to restart basal insulin therapy.

presents the self-reported reasons for persistence group membership. Multiple reasons were often selected.

Table 2. Patient-reported reasons for continuation, interruption, and discontinuation of basal insulin therapy.

Self-reported reasons for continuation of basal insulin (continuers only) include physician instruction/encouragement (35.3%) and a variety of benefits of basal insulin therapy, including short term (improved glycemic control, 71.1%) and long term (reduced complication risk, 44.8%) clinical efficacy, immediate physical (47.9%) and emotional (33.1%) wellbeing, and convenience (30.4%).

Self-reported reasons contributing to stopping basal insulin (identical response options for interrupters and discontinuers) include physician/provider instruction (interrupters/discontinuers = 19.6%/26.1%) and a variety of drawbacks of basal insulin therapy, including lack of short term clinical efficacy (hyperglycemia [11.4%/10.1%], could be managed without insulin [23.0%/26.7%]), adverse outcomes (weight gain [44.2%/37.6%], hypoglycemia [33.4%/31.0%], “potential side effects” [25.0%/19.1%]), immediate burdens (pain [28.3%/26.8%], inconvenience [21.2%/18.9%]), and cost (9.8%/17.2%).

For the two most common self-reported reasons for stopping insulin (hypoglycemia and weight gain) we are able to compare the reasons with participant self-reported incidence of these events. Of those who reported weight gain as a reason for interruption or discontinuation, only 65.9% reported incident weight gain, indicating that anticipation of weight gain could affect insulin persistence. Conversely, of those who did not report weight gain as a reason for interruption or discontinuation, 26.7% reported incident weight gain, indicating that tolerance of weight gain could also affect insulin persistence. A similar phenomenon was observed with hypoglycemia (i.e. that anticipation or tolerance of hypoglycemia could affect persistence): of those who reported a reason of hypoglycemia, only 47.7% reported incident hypoglycemia; while of those who did not report a reason of hypoglycemia, 36.7% reported incident hypoglycemia.

Self-reported reasons contributing to restarting/potentially restarting basal insulin among interrupters/discontinuers include persuasion by physician/provider (71.4%/69.2%) and family/friends (38.7%/33.1%), uncontrolled blood sugar (27.2%/36.4%), and resolution of the issue that caused stopping (interrupters only [11.4%]). Among interrupters who reported that they restarted insulin due to high blood sugar, 51.6% reported having high blood sugar upon stopping insulin, compared to 45.2% of those who did not report this as a reason for stopping insulin. Again, for this factor it is not clear whether the decisions were a result of the occurrence of this event, or the patients’ tolerance for the event (and again we do not know the actual level of hyperglycemia experienced by these groups).

shows the results of multivariate regression analyses, and illustrates the regression analysis outcomes. The overall regression models for all outcomes were statistically significant (p < .001), with R2 ranging from 21.9% to 33.8% of variance explained. All blockwise results were statistically significant (p < .05), with the exception of insulin cessation experience for repeat interruption. Demographic and disease factors accounted for 8.0%–25.8% of variance explained, insulin initiation experience factors accounted for an additional 2.4%–5.3% of variance explained, insulin use experience factors accounted for an additional 3.3%–9.6% of variance explained and insulin cessation experience factors accounted for an additional 2.2%–3.4% of variance explained (where statistically significant).

Table 3. Regression analysis results.

Many variables were not significantly related to any of the outcomes, e.g. the provider who patients reported as having recommended insulin initiation and patient-reported training and support prior to and during initiation of insulin. Nineteen of the factors examined were significantly associated with one or more of the outcomes, seven with more than one outcome (none with all outcomes), with three being demographic and disease factors (age, gender, prior oral treatment) and four being patient experiences (perceived diabetes severity, insulin burden, physician recommendation for insulin stoppage, and hyperglycemia post-cessation). For these seven factors associated with more than one outcome, we can assess whether there is a pattern of consistency in the associations. That is, a simple consistency would be that a factor associated with increased risk of cessation would be associated with an increased risk of non-resumption and repeat interruption, as well as an increased perceived likelihood of non-resumption. Results for demographic and disease factors are mixed in this regard (completely consistent for none of three demographic and disease factors), but more consistent for patient experiences (completely consistent for two of four patient experience factors). Significant associations for each outcome are reported below.

Cessation of basal insulin for those who did or did not resume basal insulin use was significantly more common for those who were male, younger, had diabetes for a longer time, previously used an oral non-insulin injected anti-hyperglycemic medication, saw their diabetes as less severe at initiation, and worried more about insulin prior to initiation. Cessation was significantly less common for those who used a pen when initiating insulin, and more common among those who experienced weight gain and difficulties during insulin use.

Non-resumption of basal insulin after cessation was significantly more common among those who were female and had not previously used an oral diabetes medication. Non-resumption was significantly more common among those who had greater burden using basal insulin and less common for those who had experienced elevated blood glucose upon cessation of basal insulin. Those who stopped using insulin because of cost or physician instructions were significantly less likely to resume.

Repeat interruption of basal insulin among those who resumed basal insulin after cessation was significantly more common among those who were younger, had prescription coverage and who had experienced uncontrolled hyperglycemia and greater burden with basal insulin use.

Subjective likelihood of basal insulin non-resumption among those who had discontinued basal insulin was significantly higher among those who were older, saw their diabetes as more severe, whose views were not considered during the decision to initiate basal insulin, and who stopped using insulin because of physician instructions, and was lower among those who had experienced hypoglycemia, positive impacts, more insulin burden during basal insulin use, and elevated blood glucose upon cessation of basal insulin.

Discussion

One of the most obvious findings of this study is purely descriptive – physician recommendations were a major patient-reported reason/motivation for continuation (35.3%), interruption (19.6%), resumption (71.4%), and discontinuation (26.1%) of insulin therapy. And this may be an underestimation because some reported reasons that might have been physician driven did not mention the physician (e.g. interruption to assess whether diabetes could be managed without insulin, 23.0%). We know from studies of other treatment strategies that physician recommendations are critical factors in patient decisionsCitation21,Citation22. In the case of basal insulin initiation, physicians may use insulin to reduce blood glucose to a level that oral anti-hyperglycemic agents might be able to maintainCitation23, which could be a cause of temporary cessation (if unsuccessful) or long-term cessation (if successful). Physicians may also recommend temporary (or permanent) cessation for medical reasons, e.g. frequent and/or severe hypoglycemia. In these instances, patient related factors (disease characteristics and treatment beliefs and perceptions) are not the key to understanding the pattern of persistence (if analytic samples are not purified or controlled for as done in this study, analysis will tend to underestimate the associations of patient-related factors with persistence). Our regression analysis showed that physician-driven cessation was associated with greater likelihood of non-resumption and subjective likelihood of future non-resumption among discontinuers.

A similar set of findings was observed for medication cost. That was cited as a major patient-reported reason/motivation for interruption (9.8%) and discontinuation (17.2%) of insulin therapy, and was significantly associated with an increased risk for non-resumption of insulin in the multivariate analysis. It should be noted that the importance of cost varies by country, and is more important among the more disadvantaged subgroups in the countries where insulin is costly. As noted in our methodological description, failure to control for physician-driven and cost-driven decisions obscures the role of patient beliefs, perceptions and experiences.

Some results of the statistical analysis of patient-related correlates of aspects of persistence were as expected, e.g. elevated hyperglycemia upon cessation and positive impact of basal insulin were associated with lower risk of non-resumption and higher subjective likelihood of resumption; consideration of patient views in the initiation decision and lower perceived diabetes severity were associated with higher subjective likelihood of basal insulin resumption; insulin use difficulties were associated with increased risk of cessation; insulin burden was associated with increased risk of non-resumption. These results require little interpretation, and are consistent with the self-reported reasons reported for each persistence pattern, i.e. benefits are common among continuers and drawbacks are common among interrupters and discontinuers. For example, weight gain was associated with increased risk of cessation in the regression analysis, and it was the most commonly reported reason for insulin interruption (44.2%) and discontinuation (37.6%).

Some of the statistical analysis results require interpretation. For example, prior use of non-insulin injected diabetes medication was associated with an increased risk of cessation; this might be due to comparison of different injected medications or a desire not to take multiple injections. However, in claims database analyses prior use of injectable anti-hyperglycemic medications was associated with greater basal insulin persistenceCitation16,Citation24. Prior use of oral anti-hyperglycemic medication was associated with lower risk of basal insulin non-resumption; this may be due to a realization that insulin was a viable alternative to failed oral medication therapy.

Another question is why discontinuers who experienced hypoglycemia during basal insulin therapy reported being more likely to restart. While hypoglycemia was a commonly reported reason for interrupting (33.4%) or discontinuing (31.0%) insulin use in this study, persons who cited hypoglycemia as a reason were not significantly more likely to report having experienced it. It may be that cessation due to hypoglycemia is temporary, perhaps at the behest of the physician (e.g. adjusting therapy or waiting for recovery of hypoglycemia awareness). Once the reason for hypoglycemia-related discontinuation is resolved, resumption may be likely. This may also attest to the glucose lowering power of insulin, the perceived lack of which is a barrier to resumption.

The results regarding repeat interruption are curious in themselves, i.e. repeat interruption is more common among those with prescription medication coverage, uncontrolled hyperglycemia and increased insulin use burden. However, it is important to recognize that this is a complex outcome that represents both multiple stoppages (a negative contribution to persistence) and multiple re-starts (a positive contribution to persistence). Thus patients who experience hyperglycemia and increased burden may have more stoppages while those with insurance coverage have more ability to restart. Unfortunately, the nature of the data does not allow us to separate out the factors associated with the multiple stoppages from those associated with the multiple restarts. At this point there is relatively little data regarding persons who interrupt and restart insulin treatment (as opposed to those who omit their medication intermittently), let alone those who go through multiple interruptions. However, this is an important subgroup of patients, and existing data suggests that this group has worse health outcomesCitation15. Future research should seek to determine the role that interruptions play in the long-term persistence or discontinuation of basal insulin use.

Two demographic factors were related to more than one outcome, but the associations seem inconsistent across outcomes. One example is that increasing age is associated with a decreased risk of basal insulin cessation and repeat interruption, but also an increased subjective likelihood of non-resumption among discontinuers. The former finding is supported by several studies that have found a significant association between older age and increased likelihood of insulin persistence among T2DM patientsCitation15–17,Citation24, but the latter finding is not well documented elsewhere. Another inconsistency regarding demographics is that men are more likely to stop using basal insulin, but less likely to continue the period of cessation. Some prior studies have found that male gender is associated with significantly higher odds of persistenceCitation15,Citation16, while others have not been able to detect an association between insulin persistence and genderCitation24,Citation25. It is unlikely that age and gender have an intrinsic relationship to these persistence outcomes, suggesting that other factors are responsible for these associations (e.g. patient or physician perceptions). Because other factors in the study were controlled by the analyses, we must look elsewhere for potential mediators that account for these associations.

Finally, one result seems paradoxical. Greater insulin use burden is associated with higher subjective likelihood of basal insulin resumption. This is not due to multi-collinearity (i.e. sign reversal due to high correlation with another predictor). Moreover, high insulin burden is associated with a greater risk of non-resumption and repeat interruption, as would be expected, suggesting that there is not a flaw in the measure or analysis. This finding should be confirmed before accepting it as meaningful, but if it is confirmed possible explanations should be examined.

We should note one major methodological finding regarding our two types of analyses and the results they generate. Our findings regarding self-reported reasons for persistence outcomes indicate that hypoglycemia and weight gain are major reasons for non-persistence. However, the reported incidence of hypoglycemia was not related to lower persistence for any of the outcome measures and weight gain was associated with only one. Further examination indicated that these self-reported reasons often took place among people who did not report the adverse event, and many who reported the adverse event did not report it as a reason for non-persistence. Thus, at least for these two reasons their impact may be a matter of patient anticipation (i.e. some report the event as a reason even though they do not report the event) and interpretation/tolerance (i.e. some report the event but do not report the event as a reason) as much as the actual occurrence of the events themselves (although we do not know the amount of weight gain or frequency/severity of hypoglycemia experienced by these different subgroups).

There are of course limitations to this study. Data is entirely patient self-report, so we cannot assess the role of objective factors such as level of glycemic control or specific medication and dosage prior to insulin initiation. And some potentially interesting factors were not examined, e.g. whether insulin therapy was initiated in an inpatient or outpatient setting. The data is cross-sectional and we could not observe changes in factors over time. The study design allowed us to perform case–control analyses to compare analytic cohorts, but all analyses are retrospective and it is not possible to assess prospective relationships, e.g. the change in persistence rates over the time since initiation of insulin therapy. The lack of in-depth interview data leaves us to speculate about the nature of the decision-making processes that led to the various outcomes. Finally, online survey panels may not be representative of the populations from which they are drawn. For example, the age of respondents is not typical of people with T2DM initiating insulin therapy with over 55% under the age of 40. For over 34% of patients, insulin was their first anti-hyperglycemic medication, and over 24% had received a non-insulin injectable anti-hyperglycemic medication before receiving basal insulin. The strengths of the study include the large sample size, the multi-national population, and the breadth of factors investigated.

The objective of this study was to identify patient-reported reasons for various insulin therapy persistence outcomes and the factors associated with these outcomes. While numerous findings have emerged, further research is needed to understand the nature of the observed findings. Prospective longitudinal data regarding the outcomes and their correlates over time would provide a clearer understanding of the nature of their associations. In-depth qualitative interviews of participants when a change in status occurs would provide a clearer understanding of the way that various factors entered into decisions being made. Finally, it would be important to include healthcare providers in future research to better understand their role in therapy persistence.

Conclusion

The most important implication of this study’s findings is that persistence with basal insulin therapy is a complex process which unfolds over time. It involves a dynamic interplay between patient and healthcare provider reflecting the inputs of both the ways that those inputs are driven by situational factors (emergent events and experiences) as well as stable predisposing factors (demographic/disease characteristics and treatment beliefs). The meaning and impact of various factors appear to change over the course of treatment and must be understood within the immediate contexts within which treatment decisions are made. It is therefore critical for the provider and patient to establish a trusting relationship which allows for ongoing open discussion of issues surrounding the management of insulin treatment. Just as there is currently no one-time cure for type 2 diabetes, there is no one-time solution for its treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by Eli Lilly and Company and Boehringer Ingelheim. The sponsor reviewed and provided comments on this article.

Author contributions: M.P., M.P.-N., D.C., J.I., S.K. and I.H. were involved in the conception and design of this study. M.P. and L.S. were involved in the analysis of the data. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data. M.P. developed the manuscript draft. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content, provided a final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

M.P. has disclosed that he has received consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca, Calibra, Lilly, and Novo Nordisk, lecture fees from Lilly and Novo Nordisk, and has served on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Calibra, Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. M.P.-N., D.C., S.K. and I.H. have disclosed that they are employees of Eli Lilly and Company. J.I. and L.S. have disclosed that they are employees of Analysis Group Inc., which has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Company. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Previous presentation: A synopsis for part of the current research was presented in poster format: Peyrot M, Ivanova JI, Zhao C, et al. Reasons for different patterns of basal insulin persistence after initiation among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–14 June 2016.

References

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, et al. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1577-89

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405-12

- World Health Organization. Diabetes Fact Sheet: World Health Organization 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/. [Last accessed 5 July 2017]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2016. Diabetes Care 2016;39(Suppl 1):S1-S110

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al.; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012;35:1364-79

- Capoccia K, Odegard PS, Letassy N. Medication adherence with diabetes medication: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ 2016;42:34-71

- Gonzalez J, Peyrot M, McCarl A, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2398-403

- Peyrot M, Rubin R, Kruger D, et al. Correlates of insulin injection omission. Diabetes Care 2010;33:243-8

- Peyrot M, Barnett A, Meneghini L, et al. Factors associated with injection omission/non-adherence in the Global Attitudes of Patients and Physicians in Insulin Therapy (GAPP) study. Diabetes Obes Metabol 2012;14:1081-7

- Peyrot M, Rubin R, Khunti K. Addressing barriers to initiation of insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Primary Care Diabetes 2010;4(Suppl 1):S11-S18

- Peyrot M, Rubin R, Lauritzen T, et al. Resistance to insulin therapy among patients and providers: results of the cross-national DAWN study. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2673-9

- Larkin ME, Capasso VA, Chen CL, et al. Measuring psychological insulin resistance: barriers to insulin use. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:511-17

- Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Guzman S, et al. Psychological insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: the scope of the problem. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2543-5

- Peyrot M, Skovlund S. Willingness to initiate/intensify medications in the 2nd Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN2) study. Late Breaking Abstract. American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, 2014

- Ascher-Svanum H, Lage MJ, Perez-Nieves M, et al. Early discontinuation and restart of insulin in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Ther 2014;5:225-42

- Perez-Nieves M, Kabul S, Desai U, et al. Basal insulin persistence, associated factors, and outcomes after treatment initiation among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:669-80

- Yavuz DG, Ozcan S, Deyneli O. Adherence to insulin treatment in insulin-naive type 2 diabetic patients initiated on different insulin regimens. Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:1225-31

- Davies M, Storms S, Shutler S, et al. Improvement of glycemic control in subjects with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: comparison of two treatment algorithms using insulin glargine. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1282-8

- Mosenzon O, Raz I. Intensification of insulin therapy for type 2 diabetic patients in primary care: basal–bolus regimen versus premix insulin analogs. When and for whom? Diabetes Care 2013;36(Suppl 2):S212-S18

- Perez-Nieves M, Ivanova JI, Hadjiyianni I, et al. Basal insulin initiation use and experience among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus with different patterns of persistence: results from a multi-national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 201710:1-25

- Rubin R, Peyrot M. Factors affecting use of insulin pens by patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008;31:430-2

- Peyrot M, Rubin R. Factors associated with persistence and resumption of insulin pen use for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Therapeut 2011;13:43-8

- Ryan E, Imes S, Wallace C. Short-term intensive insulin therapy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1028-32

- Wei W, Pan C, Xie L, et al. Real-world insulin treatment persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract 2014;20:52-61

- Cooke CE, Lee HY, Tong YP, et al. Persistence with injectable antidiabetic agents in members with type 2 diabetes in a commercial managed care organization. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:231-8